Theory of International Politics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2

Ilia State University Faculty of Arts and Sciences MA Level Course Syllabus 1. Theory of War and Peace: Theories and Cases COURSE TITLE 2. Spring Term COURSE DURATION 3. 6.0 ECTS 4. DISTRIBUTION OF HOURS Contact Hours • Lectures – 14 hours • Seminars – 12 hours • Midterm Exam – 2 hours • Final Exam – 2 hours • Research Project Presentation – 2 hours Independent Work - 118 hours Total – 150 hours 5. Nino Pavlenishvili INSTRUCTOR Associate Professor, PhD Ilia State University Mobile: 555 17 19 03 E-mail: [email protected] 6. None PREREQUISITES 7. Interactive lectures, topic-specific seminars with INSTRUCTION METHODS deliberations, debates, and group discussions; and individual presentation of the analytical memos, and project presentation (research paper and PowerPoint slideshow) 8. Within the course the students are to be introduced to COURSE OBJECTIVES the vast bulge of the literature on the causes of war and condition of peace. We pay primary attention to the theory and empirical research in the political science and international relations. We study the leading 1 theories, key concepts, causal variables and the processes instigating war or leading to peace; investigate the circumstances under which the outcomes differ or are very much alike. The major focus of the course is o the theories of interstate war, though it is designed to undertake an overview of the literature on civil war, insurgency, terrorism, and various types of communal violence and conflict cycles. We also give considerable attention to the methodology (qualitative/quantitative; small-N/large-N, Case Study, etc.) utilized in the well- known works of the leading scholars of the field and methodological questions pertaining to epistemology and research design. -

Types of Dance Styles

Types of Dance Styles International Standard Ballroom Dances Ballroom Dance: Ballroom dancing is one of the most entertaining and elite styles of dancing. In the earlier days, ballroom dancewas only for the privileged class of people, the socialites if you must. This style of dancing with a partner, originated in Germany, but is now a popular act followed in varied dance styles. Today, the popularity of ballroom dance is evident, given the innumerable shows and competitions worldwide that revere dance, in all its form. This dance includes many other styles sub-categorized under this. There are many dance techniques that have been developed especially in America. The International Standard recognizes around 10 styles that belong to the category of ballroom dancing, whereas the American style has few forms that are different from those included under the International Standard. Tango: It definitely does take two to tango and this dance also belongs to the American Style category. Like all ballroom dancers, the male has to lead the female partner. The choreography of this dance is what sets it apart from other styles, varying between the International Standard, and that which is American. Waltz: The waltz is danced to melodic, slow music and is an equally beautiful dance form. The waltz is a graceful form of dance, that requires fluidity and delicate movement. When danced by the International Standard norms, this dance is performed more closely towards each other as compared to the American Style. Foxtrot: Foxtrot, as a dance style, gives a dancer flexibility to combine slow and fast dance steps together. -

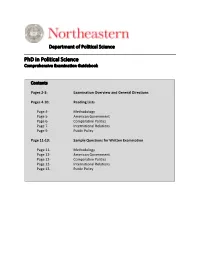

Phd in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook

Department of Political Science __________________________________________________________ PhD in Political Science Comprehensive Examination Guidebook Contents Pages 2-3: Examination Overview and General Directions Pages 4-10: Reading Lists Page 4- Methodology Page 5- American Government Page 6- Comparative Politics Page 7- International Relations Page 9- Public Policy Page 11-13: Sample Questions for Written Examination Page 11- Methodology Page 12- American Government Page 12- Comparative Politics Page 12- International Relations Page 13- Public Policy EXAMINATION OVERVIEW AND GENERAL DIRECTIONS Doctoral students sit For the comprehensive examination at the conclusion of all required coursework, or during their last semester of coursework. Students will ideally take their exams during the fifth semester in the program, but no later than their sixth semester. Advanced Entry students are strongly encouraged to take their exams during their Fourth semester, but no later than their FiFth semester. The comprehensive examination is a written exam based on the literature and research in the relevant Field of study and on the student’s completed coursework in that field. Petitioning to Sit for the Examination Your First step is to petition to participate in the examination. Use the Department’s graduate petition form and include the following information: 1) general statement of intent to sit For a comprehensive examination, 2) proposed primary and secondary Fields areas (see below), and 3) a list or table listing all graduate courses completed along with the Faculty instructor For the course and the grade earned This petition should be completed early in the registration period For when the student plans to sit For the exam. -

State Failure in Developing Countries and Strategies of Institutional Reform

State Failure in Developing Countries and Strategies of Institutional Reform Mushtaq H. Khan Department of Economics, SOAS, University of London. Abstract: The analysis of state failure and the policy debate have been driven by two very different underlying views of what the state does. The first, which we call the “service- delivery” view says the role of the state is to provide law and order, stable property rights, key public goods and welfarist redistributions. In failing to provide these, state failure contributes to economic under-performance and poverty. State failure of this type is in turn related to an inter-dependent constellation of governance failures including corruption and rent-seeking, distortions in markets and the absence of democracy. All of these need to be addressed to focus the state on its core service-delivery tasks. The second locates the developing country state in the context of “social transformation”: the dramatic transition these countries are going through as traditional production systems collapse and a capitalist economy begins to emerge. Dynamic transformation states have heavily intervened in property rights and devised rent-management systems to accelerate the capitalist transition and the acquisition of new technologies. State failure according to this view has been driven by the lack of institutional capacities in these respects, and more importantly, the incompatibility of institutional capacities with pre-existing distributions of power. An examination of the econometric data and historical evidence raises serious doubts as to whether the governance reforms suggested by the first view can improve growth, while the need for reforms identified by the second view are much better supported. -

Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka

118 Bizourka and Freestyle Flemish Mazurka (Flanders, Belgium, Northern France) These are easy-going Flemish mazurka (also spelled mazourka) variations which Richard learned while attending a Carnaval ball near Dunkerque, northern France, in 2009. Participants at the ball were mostly locals, but also included dancers from Belgium and various parts of France. Older Flemish mazurka is usually comprised of combina- tions of the Mazurka Step and Waltz, in various simple patterns (see Freestyle Flemish Mazurka below). Like most folk mazurkas, their style descended from the Polka Mazurka once done in European ballrooms, over 150 years ago. This folk process is sometimes compared to a bridge. French or English dance masters picked up an ethnic dance step, in this case a mazurka step from the Polish Mazur, and standardized it for ballroom use. It was then spread throughout the world by itinerant dance teachers, visiting social dancers, and thousands of easily available dance manuals. From this propagation, the most popular steps (the Polka Mazurka was indeed one of the favorites) then “sank” through many simplified forms in villages throughout Europe, the Americas, Australia and elsewhere. In other words, towns in rural France or England didn’t get their mazurka step directly from Poland, or their polka directly from Bohemia, but rather through the “bridge” of dance teachers, traveling social dancers and books, that spread the ballroom versions of the original ethnic steps throughout the world. Once the steps left the formal setting of the ballroom, they quickly simplified. Then folk dances evolve. Typically steps and styles are borrowed from other dance forms that the dancers also happen to know, adding a twist to a traditional form. -

Mumbai Law and Economics of Institutions

Instructor: Jayati Sarkar email: [email protected] skype id: jayati.sarkar13 LAW AND ECONOMICS OF INSTITUTIONS EMLE Third Term: April – June 2020 Indira Gandhi Institute of Development Research, Mumbai, INDIA Course Description This course is designed to expose the student to fundamental theoretical perspectives and empirical research that have developed over the years to study the emergence and functions of institutions, with special emphasis placed on law as an institution. Insights gained in the course will be helpful in understanding the role of institutions in development, and in analysing the process of economic change. The course is divided into three main sections, namely (i) why study institutions matter (ii) theoretical perspectives in institutional economics, and (iii) how institutions matter. Topics covered under these sections include how social, political and legal institutions impact economic development, bounded rationality and institutions, the function of institutions in mitigating collective action problems, rent seeking, interest groups and policy formulation, role of institutions in reduction of transaction costs and the role of rules and norms in coordinating and protecting institutions. Course Requirement In view of the Covid 19 pandemic, the course this year will be in the form of self study with directed readings as specified in this reading list. Soft copies of all readings in this list will be provided to you.. Power point presentations of lectures that go with the readings will also be sent to you on pre-specified dates. There will be 12 such power points presentations to be covered over a span of four weeks. In these four weeks, we will meet online via Skype every Tuesday at a mutually convenient time to discuss any questions that you may have on the lecture notes and readings. -

Must War Find a Way?167

Richard K. Betts A Review Essay Stephen Van Evera, Causes of War: Power and the Roots of Conict Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1999 War is like love, it always nds a way. —Bertolt Brecht, Mother Courage tephen Van Evera’s book revises half of a fteen-year-old dissertation that must be among the most cited in history. This volume is a major entry in academic security studies, and for some time it will stand beside only a few other modern works on causes of war that aspiring international relations theorists are expected to digest. Given that political science syllabi seldom assign works more than a generation old, it is even possible that for a while this book may edge ahead of the more general modern classics on the subject such as E.H. Carr’s masterful polemic, 1 The Twenty Years’ Crisis, and Kenneth Waltz’s Man, the State, and War. Richard K. Betts is Leo A. Shifrin Professor of War and Peace Studies at Columbia University, Director of National Security Studies at the Council on Foreign Relations, and editor of Conict after the Cold War: Arguments on Causes of War and Peace (New York: Longman, 1994). For comments on a previous draft the author thanks Stephen Biddle, Robert Jervis, and Jack Snyder. 1. E.H. Carr, The Twenty Years’ Crisis, 2d ed. (New York: Macmillan, 1946); and Kenneth N. Waltz, Man, the State, and War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1959). See also Waltz’s more general work, Theory of International Politics (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1979); and Hans J. -

Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work

AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Reviewer Fatigue? Why Scholars PS Decline to Review Their Peers’ Work | Marijke Breuning, Jeremy Backstrom, Jeremy Brannon, Benjamin Isaak Gross, Announcing Science & Politics Political Michael Widmeier Why, and How, to Bridge the “Gap” Before Tenure: Peer-Reviewed Research May Not Be the Only Strategic Move as a Graduate Student or Young Scholar Mariano E. Bertucci Partisan Politics and Congressional Election Prospects: Political Science & Politics Evidence from the Iowa Electronic Markets Depression PSOCTOBER 2015, VOLUME 48, NUMBER 4 Joyce E. Berg, Christopher E. Peneny, and Thomas A. Rietz dep1 dep2 dep3 dep4 dep5 dep6 H1 H2 H3 H4 H5 H6 Bayesian Analysis Trace Histogram −.002 500 −.004 400 −.006 300 −.008 200 100 −.01 0 2000 4000 6000 8000 10000 0 Iteration number −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Autocorrelation Density 0.80 500 all 0.60 1−half 400 2−half 0.40 300 0.20 200 0.00 100 0 10 20 30 40 0 Lag −.01 −.008 −.006 −.004 −.002 Here are some of the new features: » Bayesian analysis » IRT (item response theory) » Multilevel models for survey data » Panel-data survival models » Markov-switching models » SEM: survey data, Satorra–Bentler, survival models » Regression models for fractional data » Censored Poisson regression » Endogenous treatment effects » Unicode stata.com/psp-14 Stata is a registered trademark of StataCorp LP, 4905 Lakeway Drive, College Station, TX 77845, USA. OCTOBER 2015 Cambridge Journals Online For further information about this journal please go to the journal website at: journals.cambridge.org/psc APSA Task Force Reports AMERICAN POLITICAL SCIENCE ASSOCIATION Let’s Be Heard! How to Better Communicate Political Science’s Public Value The APSA task force reports seek John H. -

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma?

Was the Cold War a Security Dilemma? Robert Jervis xploring whether the Cold War was a security dilemma illumi- nates botEh history and theoretical concepts. The core argument of the security dilemma is that, in the absence of a supranational authority that can enforce binding agreements, many of the steps pursued by states to bolster their secu- rity have the effect—often unintended and unforeseen—of making other states less secure. The anarchic nature of the international system imposes constraints on states’ behavior. Even if they can be certain that the current in- tentions of other states are benign, they can neither neglect the possibility that the others will become aggressive in the future nor credibly guarantee that they themselves will remain peaceful. But as each state seeks to be able to pro- tect itself, it is likely to gain the ability to menace others. When confronted by this seeming threat, other states will react by acquiring arms and alliances of their own and will come to see the rst state as hostile. In this way, the inter- action between states generates strife rather than merely revealing or accentuat- ing con icts stemming from differences over goals. Although other motives such as greed, glory, and honor come into play, much of international politics is ultimately driven by fear. When the security dilemma is at work, interna- tional politics can be seen as tragic in the sense that states may desire—or at least be willing to settle for—mutual security, but their own behavior puts this very goal further from their reach.1 1. -

Are We There Yet? IZA DP No

IZA DP No. 6934 Are We There Yet? Time for Checks and Balances on New Institutionalism Murat Iyigun October 2012 DISCUSSION PAPER SERIES Forschungsinstitut zur Zukunft der Arbeit Institute for the Study of Labor Are We There Yet? Time for Checks and Balances on New Institutionalism Murat Iyigun University of Colorado and IZA Discussion Paper No. 6934 October 2012 IZA P.O. Box 7240 53072 Bonn Germany Phone: +49-228-3894-0 Fax: +49-228-3894-180 E-mail: [email protected] Any opinions expressed here are those of the author(s) and not those of IZA. Research published in this series may include views on policy, but the institute itself takes no institutional policy positions. The IZA research network is committed to the IZA Guiding Principles of Research Integrity. The Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA) in Bonn is a local and virtual international research center and a place of communication between science, politics and business. IZA is an independent nonprofit organization supported by Deutsche Post Foundation. The center is associated with the University of Bonn and offers a stimulating research environment through its international network, workshops and conferences, data service, project support, research visits and doctoral program. IZA engages in (i) original and internationally competitive research in all fields of labor economics, (ii) development of policy concepts, and (iii) dissemination of research results and concepts to the interested public. IZA Discussion Papers often represent preliminary work and are circulated to encourage discussion. Citation of such a paper should account for its provisional character. A revised version may be available directly from the author. -

ROUND DANCE BASICS TWO STEP - PHASE I TOUCH, (Action) DIRECTIONS: - Action Touching Free Foot Toe at Supp

ROUND DANCE BASICS TWO STEP - PHASE I TOUCH, (Action) DIRECTIONS: - Action touching free foot toe at supp. foot instep. - Line Of Dance, Reverse Line Of Dance, - Other actions; (STAMP, TAP, HEEL, TOE) - Wall, Center Of Hall. (Diagonals) POINT, (Action) POSITIONS: - Action touching free ft. toe in direction indicated. - Open, Left-Open, Closed, Semi-Closed, - Apart,-, Point,-; Together,-, Touch,-; (Std. Intro.) - Butterfly, Sdcar, and Banjo. TWIRL "N". ASSUMED POSITION: - Man Fwd "n", Lady Twirls Right Face in "n". - In OPEN, if cued to face partner w/o position cue, - Twirl,-,2,-; Apt,-,Pt,-; (Frequent dance ending) - Then assumed position is BUTTERFLY. - In SEMI, if cued to face partner w/o position cue, ******** (HOT TIME MIXER) ******* - Then assumed position is CLOSED. BLENDING: WALK,-, (S) - Graceful transition from one position to another. - A step in line of progression taking 2 beats - In OPEN, blend to SEMI, etc. - Open, Closed, Semi-Closed.... - Other Walking steps; STRUT, STROLL, SWAGGER STARTING FOOTWORK: - WALK "N" - Take "n" walking steps. - Man's Left Foot, Lady's Right Foot. - Lead Foot, Trailing Foot RUN, (Q) - A step in line of progression taking 1 beat FREE FOOT, SUPPORTING FOOT: - RUN "N" - Take "n" running steps. - The foot that has no weight on it is the "Free Foot" - The foot that has weight is the "Supporting Foot". CIRCLE WALK AWAY or TOGETHER "N". - Walk in a circular pattern away/to partner "n" steps. CUEING PRACTICES - Cues are directed to Man's footwork CIRCLE WALK AWAY & TOGETHER;; (SS,SS) - Cues for next series of footwork occur prior to use. - 2 steps away from partner, 2 steps towards partner. -

Law and Economics: Its Glorious Past and Cloudy Future Richarda

Law and Economics: Its Glorious Past and Cloudy Future RichardA. Epsteint The title I have given to this short comment is one that does not speak to any great optimism about the future of Law and Economics, and it is incumbent upon me, even in a short essay, to indicate the sources of my uneasiness. When I entered legal academia in 1968, Law and Economics was just getting started as a separate field. The magnitude of the intellectual revolution is hard to recount today because virtually everyone who works in common law subjects is familiar with the now routine exercise of showing why it is, or has to be, the case that this or that common law rule is, or is not, efficient. But the present familiarity should not be read back into the past. In my student days at Oxford be- tween 1964 and 1966, I engaged in an exhaustive study of the common law of contract, property, and torts. I studied legal his- tory and jurisprudence, and learned Roman and international law to boot, all with reference to contract, property, and torts. Yet I cannot recall a single instance in which common law rules were praised for their efficient properties or criticized for their lack thereof. For our normative work, we relied on some intuitive notion of fairness or justice, which seemed to produce on average better economic results than the self-conscious instrumentalism that guides so many judges today. For our descriptive work, we relied on stare decisis and close case readings. To be sure, English academics and judges were less innova- tive than their American counterparts.