At the Heart of Art and Earth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Living Transformative Lives

Living Transformative Lives Finnish Freelance Dance Artists Brought into Dialogue with Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology Leena Rouhiainen Doctoral Dissertation ACTA SCENICA 13 Näyttämötaide ja tutkimus Teatterikorkeakoulu - Scenkonst och forskning - Teaterhögskolan - Scenic art and research - Theatre Academy Leena Rouhiainen Living Transformative Lives Finnish Freelance Dance Artists Brought into Dialogue with Merleau-Ponty’s Phenomenology Doctoral dissertation Theatre Academy, Department of Dance and Theatre Pedagogy Publisher: Theatre Academy © Theatre Academy and Leena Rouhiainen Cover: Jussi Konttinen Lay-out: Tanja Nisula ISBN: 952-9765-32-0 ISSN: 1238-5913 Printed in Edita, Helsinki 2003 Contents Acknowledgements 7 Preamble 9 PART ONE – METHODOLOGY, METHODS, AND PROCEDURES 13 1 On the Process, Purpose, and Objectives of the Investigation 16 2 The Methodological Context 21 2.1 The Nature and Research Interest of the Investigation 25 2.2 The Validity of the Research 28 3 Interviews as Research Material 33 3.1 The Interviewees 34 3.2 Conducting and Recording the Interviews 39 3.3 Transcribing the Recordings 45 4 The Methodological Principles Directing the Analysis of the Interview Material 46 4.1 A Hermeneutical and Existential Phenomenological Approach 49 4.2 The Hermeneutical Dialogue 54 4.3 Language as a Source of Meaning 61 4.4 Implications of the Methodological Principles for the Analysis 68 5 The Methods and Procedures of Analyzing the Interview Material 71 5.1 The Descriptive Reading 73 5.2 The Interpretative Phenomenological - Theoretical -

Cassirer Filosofian Historiassa 54

TOIMITUSKUNTA TOIMITUSNEUVOSTO Mikko Lahtinen, päätoimittaja Aki Huhtinen, Vesa Jaaksi, Riitta Koikkalainen, puh. (k.) 931-253 4851, sähköposti [email protected] Päivi Kosonen, Jussi Kotkavirta, Petteri Limnell, Tommi Wallenius, toimitussihteeri Susanna Lindberg, Erna Oesch, Mika Ojakangas, puh. (k.) 931-345 2760, sähköposti [email protected] Sami Pihlström, Juha Romppanen, Esa Saarinen, Kimmo Jylhämö Jarkko S. Tuusvuori, Yrjö Uurtimo, Erkki Vetten- Samuli Kaarre niemi, Matti Vilkka, Mika Vuolle, Jussi Vähämäki Reijo Kupiainen Marjo Kylmänen Mika Saranpää Heikki Suominen Tuukka Tomperi Tere Vadén TÄMÄN NUMERON KIRJOITTAJAT TOIMITUKSEN OSOITE Anaksimandros, (katso takakansi). niin & näin Lilli Alanen, FT, dosentti, Suomen Akatemian vanhempi PL 730 tutkija, filosofian laitos, Helsingin yliopisto. 33101 Tampere Jari Aro, tutkija, sosiologian ja sosiaalipsykologian laitos, Tampereen yliopisto. SÄHKÖPOSTI Kimmo Jylhämö, fil.yo, Tampere. [email protected] Katri Kaalikoski, tutkija, käytännöllisen filosofian laitos, Helsingin yliopisto. Pekka Kalli, FT, filosofian ainelaitos, Tampereen yliopisto. niin & näin INTERNETISSÄ Sven Krohn, FT, professori (emeritus), filosofian laitos, http://www.netn.fi/ Turun yliopisto. Marjaana Kopperi, tutkija, käytännöllisen filosofian laitos, TILAUSHINNAT Helsingin yliopisto. Kestotilaus 12 kk kotimaahan 130 mk, Päivi Kosonen, FL, assistentti, taideaineiden laitos, Tampe- ulkomaille 180 mk. Lehtitoimiston kautta tilattaessa reen yliopisto. lisämaksu. Kestotilaus jatkuu uudistamatta kunnes tilaaja Reijo Kupiainen, FM, tutkija, -

Martin Heidegger. Cahier De 1'Herne, Paris 1983

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Trepo - Institutional Repository of Tampere University JUHA VARTO TÄSTÄ JONNEKIN MUUALLE POLKUJA HEIDEGGERISTA JUHA VARTO TÄSTÄ JONNEKIN MUUALLE POLKUJAHEIDEGGERISTA Sähköinen julkaisu ISBN 951-44-5648-3 2. painos ISBN 951-44-3783-7 Ilmestynyt vuonna 1993 sarjassa Filosofisia tutkimuksia Tampereen yliopistosta Vol XL ISBN 951-44-3184-7 ISSN 0786-647X TAMPEREEN YLIOPISTO Jäljennepalvelu Tampere 1995 Julkaisua myy TAJU. Tampereen yliopiston julkaisujen myynti PL 617 33101 TAMPERE SISÄLLYS Johdanto l Filosofi ja salaisuus 5 Filosofin laulava runoilija 21 Runon sana ja luonnon kiinniotto 40 Kielen alkuperästä 54 Länsimaisen ihmisen perustavanlaatuinen pitkästyminen 69 Heideggerin alkuperäinen etiikka 86 Mihin tiede tarvitsee perustan 103 Teknologian filosofinen ongelma ja ekologia 121 Estetiikka ja nykyaikainen ajattelu 142 Miksi taiteen ei tule olla yhteiskunnallista 155 Filosofin kariutuminen: politiikka 164 Parafraaseja eräästä kirjoituksesta 171 HEIDEGGERIN TEOKSISTA SATUNNAISESTI KÄYTETYT LYHENTEET AED Aus der Erfahrung des Denkens E Vom Ereignis EHD Erläuterungen zu Hölderlins Dichtung EiM Einführung in die Metaphysik FS Frühe Schriften G Gelassenheit GA# Gesamtausgabe Vol. GM Die Grundbegriffe der Metaphysik HA Hölderlins Hymne "Andenken". Gesamtausgabe Bd. 52. Frankfurt:Klostermann 1982. HH Hölderlins Hymnen "Germanien" und "Der Rhein". Heidegger, Gesamtausgabe Bd. 39. HW Holzwege N# Nietzsche I tai II SG Der Satz vom Grund SZ Sein und Zeit US Unterwegs zur Sprache VA Vorträge und Aufsätze WHD Was heißt Denken? WiMN Was ist Metaphysik? Nachwort. Teoksessa Wegmarken. lyhenne FITTY viittaa tähän sarjaan, Filosofisia tutkimuksia Tampereen yliopistosta Lukijalle Tähän kokoelmaan olen koonnut pidemmän ajan kuluessa muissa yhteyksissä julkaisemani artikkelit, joiden lähtökohtana tai aiheena on ollut Martin Heideggerin filosofia. -

Phenomenological Ontology of Breathing

JYU DISSERTATIONS 17 Petri Berndtson Phenomenological Ontology of Breathing The Phenomenologico-Ontological Interpretation of the Barbaric Conviction of We Breathe Air and a New Philosophical Principle of Silence of Breath, Abyss of Air JYU DISSERTATIONS 17 Petri Berndtson Phenomenological Ontology of Breathing The Phenomenologico-Ontological Interpretation of the Barbaric Conviction of We Breathe Air and a New Philosophical Principle of Silence of Breath, Abyss of Air Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston Historica-rakennuksen salissa H320 syyskuun 28. päivänä 2018 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in building Historica, auditorium H320, on September 28, 2018 at 12 o’clock noon. JYVÄSKYLÄ 2018 Editors Olli-Pekka Moisio Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Ville Korkiakangas Open Science Centre, University of Jyväskylä Copyright © 2018, by University of Jyväskylä Permanent link to this publication: http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-951-39-7552-4 ISBN 978-951-39-7552-4 (PDF) URN:ISBN:978-951-39-7552-4 ISSN 2489-9003 ABSTRACT Berndtson, Petri Phenomenological Ontology of Breathing: The Phenomenologico-Ontological Interpretation of the Barbaric Conviction of We Breathe Air and a New Philosophical Principle of Silence of Breath, Abyss of Air Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2018, 283 p. (JYU Dissertations ISSN 2489-9003; 17) ISBN 978-951-39-7552-4 (PDF) The general topic of my philosophical dissertation is phenomenological ontology of breathing. I do not investigate the phenomenon of breathing as a natural scientific problem, but as a philo- sophical question. -

Taiteen Jälki Taidepedagogiikan Polkuja Ja Risteyksiä

Taiteen jälki Taidepedagogiikan polkuja ja risteyksiä Toimittanut Eeva Anttila 40 teatterikorkeakoulun julkaisusarja Taiteen jälki Taidepedagogiikan polkuja ja risteyksiä isbn (painettu) 978-952-9765-63-8 isbn (verkkojulkaisu) 978-952-9765-64-5 issn 0788-3385 Julkaisija Teatterikorkeakoulu © Teatterikorkeakoulu Toimittaja & kirjoittajat Toimittaja Eeva Anttila Kuvat Saara Kähönen teoksesta Luovu uus. Koreografia Marja-Sisko Vuorela; esiintyjät Erika Messo, Anna Orkolainen, Katja Putkonen, Marja-Sisko Vuorela (TeaK), Ulla Leppävuori (KuvA). Teatterikorkeakoulu, tanssi- ja teatteripedagogiikan laitos, 2010. Julkaisusarjan ilme Kannen suunnittelu Sisuksen ja päällyksen muotoilu Hahmo Design Oy www.hahmo.fi Taitto Edita Prima Oy, Helsinki Painotyö & sidonta Edita Prima Oy, Helsinki, 2011 Paperi Edixion 300 g / m2 & 120 g / m2 Kirjainperhe Filosofia. © Zuzana Licko. Sisällys Johdanto 5 Prologi: Virhe taidepedagogiikan tehtävänä 13 Riku Saastamoinen Taidepedagogiikan käytäntö, tiedonala ja tieteenala: Lyhyt katsaus lyhyen historian juoneen 17 Juha Varto Kasvatuksen taide ja kasvatus taiteeseen: Taiteen yleinen ja erityinen pedagoginen merkitys John Deweyn filosofian näkökulmasta 35 Heidi Westerlund ja Lauri Väkevä Liike, rytmi ja musiikki: Jaques-Dalcrozen pedagogista perintöä jäljittämässä 57 Marja-Leena Juntunen Fenomenologinen näkemys oppimisesta taiteen kontekstissa 75 Leena Rouhiainen Taidepedagogiikka tarinoiden ja tunteiden tulkkina 95 Teija Löytönen ja Inkeri Sava Taiteet kognition ja kulttuurin kentällä 121 Marjo Räsänen Taiteen tieto -

Niin & Näin 1/05 (Pdf)

,ØHETTØJØ NIINNØIN 0, 4AMPERE N I I NN Ø I N NIINNËIN & ) , / 3 / & ) . % . ! ) + ! + ! 5 3 , % ( 4 ) .UMERO\KEVËT (INTAEUROA + A T A S T R O l T - A X 3 C H E L E R s+ATASTROlT s-AX3CHELER Pääkirjoitus 3 Mikko Lahtinen, Poliittisen filosofian mestarit Niin vai näin 5 Ari Hirvonen & Toomas Kotkas, Pahan kohtaamisesta Kohti kokemusten selkeyttä 7 Kai Alhanen & Tuukka Perhoniemi, Françoise Dastur – liian selkeä ranskalaiseksi? 9 Kai Alhanen & Tuukka Perhoniemi, Fenomenologia ja filosofian mahdollisuudet: keskustelu Françoise Dasturin kanssa Ihmisen ja luonnon katastrofit 17 Mikko Lahtinen, Maanjäristysten filosofiaa 20 Voltaire, Runo Lissabonin katastrofista 23 Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Kirje Voltairelle kaitselmuksesta 31 Ville Lähde, Luonnonkatastrofin luonto 37 Michael Byers, Yhä heikommilla jäillä Kolumni 42 Anita Seppä, Pojat, filosofia ja jalkapallo Eettisen relativismin puolustus 47 Carl-Johan Holmlund, J. L. Mackie ja epäilyn taito Max Scheler 54 Ulla Solasaari, Schelerin ajattelun taustoja 57 Max Scheler, Rakkauden ja vihan fenomenologiasta 65 Tapio Puolimatka, Ordo amoris 71 Ulla Solasaari, Tieto ja eettisyys Schelerin filosofiassa 77 Jussi Kotkavirta, Scheler ja Freud 85 Mia Salo, Pyhästä tabuksi. Pyhyyden arvo Schelerillä ja Freudilla Kolumni 92 Salla Tuomivaara, Keitä me olemme? Katsauksia 94 Ville Lähde, Elämöintiä Turussa. SFY:n kollokvio 10.–11. tammikuuta 96 Inkeri Pitkäranta, Aarteet. Kansalliskirjaston näyttely 9.3.–15.10. 2005 Kirjat 97 Jarkko Tontti (toim.), Tulkinnasta toiseen. Esseitä hermeneutiikasta (Heikki Kujansivu) 99 Hans-Georg Gadamer, Hermeneutiikka. Ymmärtäminen tieteissä ja filosofiassa (Jaakko Penttinen) 101 Marc Bloch, Historian puolustus (Markku Hyrkkänen) 103 Jared Diamond, Tykit, taudit ja teräs – ihmisen yhteiskuntien kohtalot (Ville Lähde) 105 E. M. Cioran, Katkeruuden syllogismeja (Juha Varto) 107 Juuso Rahkola, Tiedon alkuperästä. -

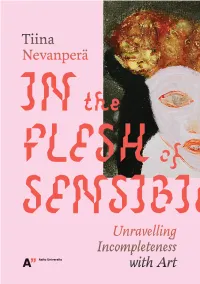

Unravelling Incompleteness with Art Contents

‘The Sirens: it seems they did indeed sing, but in an unfulfilling way, one that only gave a sign of where the real sources and real happiness of song opened. Still, by means of their imperfect songs that were only a song still to come, they did lead the sailor toward that space where singing might truly begin. They did not deceive him, in fact: they actually led him to his goal. But what happened once the place was reached? What was this place? One were there was nothing left but to disappear, because music, in this region of source and origin, had itself disap- peared more completely than in any other place in the world: sea where, ears blocked, the living sank, and where the Sirens, as proof of their good will, had also, one day, to disappear.’ Maurice Blanchot: ‘Encountering the Imaginary’ in The Book to Come, translated by C. Mandell (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2003), p. 3. Aalto University publication series DOCTORAL DiSSERTATIONS 11/2017 School of Arts, Design and Architecture Aalto artS Books Helsinki books.aalto.fi © Tiina Nevanperä DeSiGn & tYPeSettinG Safa Hovinen / Merkitys tYPeFACES Saga & Alghem by Safa Hovinen PaPer Munken Lynx 100 & 240 g/m2 iSBn 978-952-60-7255-5 (printed) iSBn 978-952-60-7254-8 (pdf) iSSn-l 1799-4934 iSSn 1799–4934 (printed) iSSn 1799–4942 (pdf) Printed in Libris, Finland 2017 Tiina Nevanperä IN the FLESH of SENSIBILITY Unravelling Incompleteness with Art Contents Abstract 6 Acknowledgements 8 introDuction Ghostly Paintings – Unravelling My Research, Its Objectives and Relevance 10 Foundations -

Martin Heideggerin Spiegel-Haastattelu Filosofia Ja Juomingit 4/95 Niin & Näin Filosofinen Aikakauslehti 4/1995

ruumiin ja liikunnan Filosofia Rousseaun itserakkaus Naiset oppineisuuden tasavallassa Martin Heideggerin Spiegel-haastattelu Filosofia ja juomingit 4/95 niin & näin filosofinen aikakauslehti 4/1995 TOIMITUSKUNTA TOIMITUSNEUVOSTO Mikko Lahtinen, päätoimittaja Aki Huhtinen, Vesa Jaaksi, Riitta Koikkalainen, puh. (k.) 931-253 4851, sähköposti [email protected] Päivi Kosonen, Jussi Kotkavirta, Petteri Limnell, Tommi Wallenius, toimitussihteeri Susanna Lindberg, Erna Oesch, Mika Ojakangas, puh. (k.) 931-345 2760, sähköposti [email protected] Sami Pihlström, Juha Romppanen, Esa Saarinen, Kimmo Jylhämö Jarkko S. Tuusvuori, Yrjö Uurtimo, Erkki Vetten- Samuli Kaarre niemi, Matti Vilkka, Mika Vuolle, Jussi Vähämäki Reijo Kupiainen Marjo Kylmänen Mika Saranpää Heikki Suominen Tuukka Tomperi Tere Vadén TOIMITUKSEN OSOITE TÄMÄN NUMERON KIRJOITTAJAT niin & näin Raimo Blom, apulaisprofessori, sosiologian ja sosiaali- PL 730 psykologian laitos, Tampereen yliopisto. 33101 Tampere Martin Heidegger, (katso sivut 4-5). Elisa Heinämäki, usk.tiet.yo, uskontotieteiden laitos, Helsingin yliopisto. SÄHKÖPOSTI Jaakko Husa, HTT, yliassistentti, julkisoikeuden laitos, [email protected] Joensuun yliopisto. Arto Jokinen, FM, taideaineiden laitos, Tampereen yliopis- TILAUSHINNAT to. Kestotilaus 12 kk kotimaahan 130 mk, Petri Koikkalainen, yht.yo, politiikan tutkimuksen laitos, ulkomaille 180 mk. Lehtitoimiston kautta tilattaessa Tampereen yliopisto. lisämaksu. Kestotilaus jatkuu Anssi Korhonen, FL, tutkija, filosofian laitos, Helsingin uudistamatta kunnes tilaaja irtisanoo -

The Pedagogy of Recognition Dancing Identity and Mutuality

RAISA FOSTER The Pedagogy of Recognition Dancing Identity and Mutuality ACADEMIC DISSERTATION To be presented, with the permission of the board of the School of Education of the University of Tampere, for public discussion in the Auditorium Pinni B 1100 Kanslerinrinne 1, Tampere, on November 24th, 2012, at 12 o’clock. UNIVERSITY OF TAMPERE ACADEMIC DISSERTATION University of Tampere School of Education Finland Copyright ©2012 Tampere University Press and the author Distribution Tel. +358 40 190 9800 Bookshop TAJU [email protected] P.O. Box 617 www.uta.fi/taju 33014 University of Tampere http://granum.uta.fi Finland Cover design by Mikko Reinikka Acta Universitatis Tamperensis 1779 Acta Electronica Universitatis Tamperensis 1253 ISBN 978-951-44-8957-0 (print) ISBN 9978-951-44-8958-7 (pdf) ISSN-L 1455-1616 ISSN 1456-954X ISSN 1455-1616 http://acta.uta.fi Tampereen Yliopistopaino Oy – Juvenes Print Tampere 2012 Acknowledgements In this artistic and educational research journey I have been accompanied by a group of inspiring people to whom I would like to extend my gratitude. I thank my supervisor, Professor Eero Ropo, at the School of Education of the University of Tampere. I am immensely grateful for his reply to my email from Australia in 2006 and his encouragement to send my research proposal to the doctoral programme of education. I have enjoyed our inspiring conversations about identity, both on a professional and a personal level. I am also deeply grateful for Eero’s understanding in letting me do this research in my own way. I pledge my gratitude to Professor Veli-Matti Värri at the School of Education of the University of Tampere. -

Hermeneutiikka

TOIMITUSKUNTA TOIMITUSNEUVOSTO Mikko Lahtinen, päätoimittaja Aki Huhtinen, Vesa Jaaksi, Riitta Koikkalainen, puh. (k.) 931-253 4851, sähköposti [email protected] Päivi Kosonen, Jussi Kotkavirta, Petteri Limnell, Tommi Wallenius, toimitussihteeri Susanna Lindberg, Erna Oesch, Mika Ojakangas, puh. (k.) 931-345 2760, sähköposti [email protected] Sami Pihlström, Juha Romppanen, Esa Saarinen, Kimmo Jylhämö Jarkko S. Tuusvuori, Yrjö Uurtimo, Erkki Vetten- Samuli Kaarre niemi, Matti Vilkka, Mika Vuolle, Jussi Vähämäki Reijo Kupiainen Marjo Kylmänen Mika Saranpää Heikki Suominen Tuukka Tomperi Tere Vadén TOIMITUKSEN OSOITE niin & näin PL 730 33101 Tampere TÄMÄN NUMERON KIRJOITTAJAT SÄHKÖPOSTI Hans-Georg Gadamer, ks. sivu 4-. [email protected] Juha Himanka, FL, tutkija, filosofian laitos, Helsingin yliopisto. Juha Holma, YTL, assistentti, politiikan tutkimuksen niin & näin INTERNETISSÄ laitos, Tampereen yliopisto. http://www.netn.fi/ Kimmo Jylhämö, FM, matemaattisten tieteiden laitos, Tampereen yliopisto. TILAUSHINNAT Pekka Kaunismaa, YTM, tutkimusassistentti, Suomen Kestotilaus 12 kk kotimaahan 130 mk, Akatemia, sosiologian laitos, Jyväskylän yliopisto. ulkomaille 180 mk. Lehtitoimiston kautta tilattaessa Petri Koikkalainen, yht. yo, politiikan tutkimuksen lisämaksu. Kestotilaus jatkuu uudistamatta kunnes tilaaja laitos, Tampereen yliopisto. irtisanoo tilauksensa tai muuttaa sen määräaikaiseksi. Pekka Kosonen, VTT, sosiologian laitos, Helsingin yliopisto. ilmestyy neljä kertaa vuodessa. niin & näin Jussi Kotkavirta, FT, assistentti, yhteiskuntatieteiden -

Liikunta Tienä Kohti Varsinaista Itseä. Liikunnan Projektien Fenomenologinen Tarkastelu

2 TIMO KLEMOLA RUUMIS LIIKKUU - LIIKKUUKO HENKI? Fenomenologinen tutkimus liikunnan projekteista. FITTY 66 TAMPERE 1998 3 ALUKSI Tämä työ on syntynyt pitkän prosessin tuloksena. Siinä kiteytyy kohta kolmekymmentä vuotta jatkunut liikuntaharrastukseni, jota jo pitkään olen pitänyt yhtenä filosofian harjoittamisen muotona. Siinä kiteytyy myös yli kaksikymmentä vuotta jatkunut "akateemisen filosofian" harrastukseni, joka on antanut käsitteellisiä välineitä erilaisiin fyysisiin harjoituksiin ja perinteisiin liittyvien kokemusten ymmärtämiseksi. Näin pitkän matkan varrella minua ovat kannustaneet ja auttaneet monet henkilöt, joita en kaikkia tässä kykene edes muistamaan. Edesmennyt filosofian professori Raili Kauppi ohjasi minua 1970-luvulla filosofiani ensiaskeleilla. Hän teki minut tietoiseksi myös filosofia perenniksestä , siitä filosofian alueesta, jonka piiriin tämänkin työn tematiikka kuuluu. Myöhemmin 1980-luvun puolivälissä zen-mestari Engaku Taino opasti minut yhteen perenniaaliseen traditioon ja sen harjoituksiin: zeniin. Tämän perinteen päämäärien ja menetelmien "kääntäminen" länsimaisen filosofian kielelle on ollutkin yksi tämän työn keskeisistä haasteista. Dosentti Juha Varto tarjosi innostavan ilmapiirin ja työskentely-ympäristön siinä vaiheessa, kun synnytimme tamperelaisen liikunnanfilosofian "koulukunnan" ja liikunnanfilosofian tutkimus- yksikön TALFIT:in 1980-luvun lopulla. Professori Veikko Rantalan tuki koko tamperelaiselle liikunnanfilosofian projektille ja myös omalle työlleni on ollut merkittävää. Haluan omistaa tämän -

On the Aestheticization of Technologized Bodies a Portrait of a Cyborg(Ed) Form of Agency JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES in HUMANITIES 319

JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 319 Mimosa Pursiainen On the Aestheticization of Technologized Bodies A Portrait of a Cyborg(ed) Form of Agency JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 319 Mimosa Pursiainen On the Aestheticization of Technologized Bodies A Portrait of a Cyborg(ed) Form of Agency Esitetään Jyväskylän yliopiston humanistis-yhteiskuntatieteellisen tiedekunnan suostumuksella julkisesti tarkastettavaksi yliopiston vanhassa juhlasalissa S212 kesäkuun 9. päivänä 2017 kello 12. Academic dissertation to be publicly discussed, by permission of the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences of the University of Jyväskylä, in Auditorium S212, on June 9, 2017 at 12o’clock noon. UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2017 On the Aestheticization of Technologized Bodies A Portrait of a Cyborg(ed) Form of Agency JYVÄSKYLÄ STUDIES IN HUMANITIES 319 Mimosa Pursiainen On the Aestheticization of Technologized Bodies A Portrait of a Cyborg(ed) Form of Agency UNIVERSITY OF JYVÄSKYLÄ JYVÄSKYLÄ 2017 Editors Mikko Yrjönsuuri Department of Social Sciences and Philosophy, University of Jyväskylä Pekka Olsbo, Sini Tuikka Publishing Unit, University Library of Jyväskylä Jyväskylä Studies in Humanities Editorial Board Editor in Chief Heikki Hanka, Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Karonen, Department of History and Ethnology, University of Jyväskylä Paula Kalaja, Department of Language and Communication Studies, University of Jyväskylä Petri Toiviainen, Department of Music, Art and Culture Studies, University of Jyväskylä