Resistance Through Space: a Comparative Study of Narrative and Space in Naked Lunch and on the Road

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

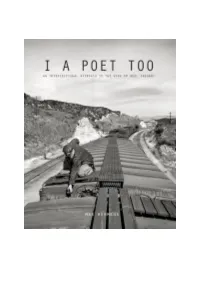

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1997 Going Nowhere Fast: The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans" Scott Patrick Moyers College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Moyers, Scott Patrick, "Going Nowhere Fast: The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans"" (1997). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626114. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a0k8-dq26 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Going Nowhere Fast The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov’sLolita and Robert Frank’sThe Americans A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott Moyers 1997 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, July 1997 Colleen Kennedy -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation

MARIA BLOSHTEYN Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation American literary history is rich with heroes of counterculture, maverick writers and poets who were rejected by the bulk of their contemporaries but inspired a cult-like following among a few devotees. The phenomenon of Beat Generation writers and poets, however, is unique in twentieth-century American letters precisely because they managed to go from marginal underground classics of the 1950s to the official voice of dissent and cultural opposition of the 1960s, a force to be reckoned with. Their books were adopted by hippies and flower children, their poems chanted at sit-ins, their lives faithfully imitated by a whole generation of young baby boomers. Their antiauthoritarian ethos along with their belief in the brotherhood of mankind were the starting point of a whole movement that gave the United States such social and cultural watersheds as Woodstock and the Summer of Love, the Chicago Riots and the Marches on Washington. The suggestion that Dostoevsky had anything to do with the American Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and street rioting in American urban centres might seem at first to be far-fetched. It is, however, a powerful testimony to Dostoevsky’s profound impact on twentieth-century American literature and culture that the first Beats saw themselves as followers of Dostoevsky and established their personal and literary union (and, as it were, the entire Beat movement) on the foundation of their shared belief in the primacy of Dostoevsky and his novels. Evidence of Dostoevsky’s impact on such key writers and poets of the Beat Generation as Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), and William Burroughs (1914-1997) is found in an almost embarrassing profusion: scattered throughout their essays, related in their correspondence, broadly hinted at and sometimes explicitly indicated in their novels and poems. -

Cal Poly the Beat Museum 211 West Franklin St

Cassady comes to Cal Poly The Beat Museum 211 West Franklin St. He’s On The Road again! Monterey, CA 93940 Phone: 831-372-4911 For Details, Contact: Press Release Robert Jordan Websites: For Release 9:00 a.m. Phone: 555-555-1234 www.thebeatmuseumonwheels.com Fax: 831-555-1234 www.kerouac.com Release Date February 7, 2005 Emai l: [email protected] THE BEAT MUSEUM ON WHEELS featuring writer John Allen Cassady with stories of his famous Beat father Neal Cassady, and Beat Generation writers Jack Kerouac, and Allen Ginsberg comes to the Spanos Theater on February 28 San Luis Obispo, CA - The Beat Museum on Wheels (www.kerouac.com), a rolling version of The Beat Museum, a museum / bookstore, located in Monterey, California, is on the move, and it’s heading for SLO Town! John Allen Cassady joins The Beat Museum on Wheels – The Beat Museum on Wheels is coming to Cal Poly’s Spanos Theatre (also known as the “Little Theatre”) in San Luis Obispo, on February 28, 2005 at 7pm. The show, entitled “This is The Beat Generation!” features writer, and musician, John Allen Cassady, playing piano, guitar, and telling stories of his famous Beat father Neal Cassady, his mother, Beat Generation muse Carolyn Cassady (“Off the Road: My Years With Cassady, Kerouac and Ginsberg”), and writers Jack Kerouac (“On The Road”), and Allen Ginsberg (“Howl”), whom he’s named after. Along with Jerry Cimino, Beat Generation Scholar owner of The Beat Museum, and www.kerouac.com, in Monterey, CA, they tell a story punctuated by dramatic readings, personal family remembrances, American history, and music that bring The Beats, and their work, to life. -

The Road Narrative in Contemporary American

THIS IS NOT AN EXIT: THE ROAD NARRATIVE IN CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN LITERATURE AND FILM by JILL LYNN TALBOT, B.S.Ed., M.A. A DISSERTATION IN ENGLISH Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Accepted Dean (C(f the Graduate School May, 1999 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my dissertation director, Dr. Bryce Conrad, for agreeing to work with me on this project and for encouraging me to remain cognizant of its scope and its overall significance, both now and in the future. Thanks also to committee member Dr. Patrick Shaw, who not only introduced me to an American fiction that I could appreciate and devote myself to in both my personal and professional life, but who has guided me from my first analysis of On the Road, which led to this project. Thanks also to committee member Dr. Bill Wenthe, for his friendship and his decision to be a part of this process. I would also like to thank those individuals who have been supportive and enthusiastic about this project, but mostly patient enough to listen to all my ideas, frustrations, and lengthy ruminations on the aesthetics of the road narrative during this past year. Last, I need to thank my true companion, who shares my love not only for roads, but certain road songs, along with all the images promised by the "road away from Here." 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii ABSTRACT v CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. THE REALITY OF THE ROAD: THE NON-FICTION ROAD NARRATIVE 2 6 John Steinbeck's Travels with Charley: In Search of America 27 William Least Heat-Moon's Blue Highways: A Journey into America 35 John A. -

An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950S Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2012 Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s Anna Lou Jessmer [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Journalism Studies Commons, and the Mass Communication Commons Recommended Citation Jessmer, Anna Lou, "Containing the Beat: An Analysis of the Press Coverage of the Beat Generation During the 1950s" (2012). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 427. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTAINING THE BEAT: AN ANALYSIS OF THE PRESS COVERAGE OF THE BEAT GENERATION DURING THE 1950S A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Journalism by Anna Lou Jessmer Approved by Robert A. Rabe, Committee Chairperson Professor Janet Dooley Dr. Terry Hapney Marshall University December 2012 ii Dedication I would like to dedicate my research to my grandfather, James D. Lee. His personal experiences during the Cold War at home and abroad inspired in me a fascination of the era at an early age. iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take a moment to acknowledge in writing, a few individuals without whom this paper would not be complete. I am incredibly and eternally grateful for Professor Robert A. -

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America Manuel Luis Martinez But invasion is the basis of fear: there’s no fear like invasion. -William S. Burroughs Barry Miles, biographer of both Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, gives a typical interpretation of the Beat phenomenon’s political significance: The group was more of a fraternity of spirit and at- titude than a literary movement, and their writings have little in common with each other; what they did have in common was a reaction to the ongoing car- nage of World War 11, the dropping of the A-bomb and the puritan small-mindedness that still char- acterized American life. They shared an interest in widening the area of consciousness, by whatever means available. (1992, 5) This quote is significant not only because of what Miles al- leges about the Beat writers, but also because of what he de- scribes as the Beat “reaction” to those postwar events commonly maintained as the most important. He suggests that a monolithic U.S. culture, in the throes of a puritanical con- servatism, was challenged by a group of heroic writers who countered its hypocrisy and blindness by “widening the area of consciousness.” The version of history that this view im- plies is troublesome for many reasons. First, it posits an axis Aztlan 23:l Spring 1998 33 Martinez of historical relations in which conservative arbiters of bour- geois culture are set against a subversive group that saves the decade by creating a liberating cultural movement, a move- ment that “widens”consciousness and presages the even more “liberating”countercultural movement of the 1960s. -

“Being the Beats: How Did the Beat Generation Shape Ideas of Gender in 1950S America?”

Page | 59 “Being the Beats: How did the Beat Generation shape ideas of gender in 1950s America?” LIANNE TAN MHIS 365 From the Beats to Big Brother Introduction From the 1950s through to the 1960s, magazines, newspapers and TV shows bombarded Americans with images of the Beat Generation.1 SimuLtaneousLy Loved and hated, the Beats was a key group that emerged in response to the suburban consumerist cuLture of 1950s America and who estabLished their identity through a rejection of the cuLtural values of their time, particuLarLy in reLation to gender expectations. The 1959 November edition of Life magazine highLighted that although the Beats were not alone in questioning the value of contemporary society and feeLing stifLed by the suburban conformity of their times, they were the onLy ones to have been sufficientLy moved to reject them by ‘voicing their quarreL with those values’.2 As writers, the cLearest infLuence of the Beats can be seen through their work, most notabLy Kerouac’s On The Road and Ginsberg’s Howl, both of which represent the importance of how popuLar cuLture can potentialLy reveal anxieties and uncertainties about gender ideoLogies often overLooked by historians.3 With reference to these texts, this essay wiLL examine the impact the Beat Generation had on the roLe of men and mascuLinity, their understanding of homosexuality, and how these focuses on being male subsequently affected their attitude towards women and women’s roLe in society. America in the 1950s Given the reactionary nature of the Beats’ ideoLogy to their time, it is important to understand the context within which the Beats were formed and how their own ideas on gender were 1 Stephen Petrus, “RumbLings of Discontent: American PopuLar CuLture and its Response to the Beat Generation, 1957-1960.” Studies in Popular Culture 20 (1997): p. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses Constructions of Identity and Otherness in Jack Kerouac's Prose MIKELLI, EFTYCHIA How to cite: MIKELLI, EFTYCHIA (2009) Constructions of Identity and Otherness in Jack Kerouac's Prose, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/29/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk CONSTRUCTIONS OF IDENTITY AND OTHERNESS IN JACK KEROUAC’S PROSE BY EFTYCHIA MIKELLI DURHAM UNIVERSITY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH STUDIES PhD THESIS MAY 2009 CONSTRUCTIONS OF IDENTITY AND OTHERNESS IN JACK KEROUAC’S PROSE Mikelli, E. PhD Thesis, Durham University, 2009. This thesis is inspired by the abiding academic and public interest in Kerouac’s work and aims to advance new readings of Kerouac’s prose in a contemporary literary and cultural context. It is particularly concerned with a deconstructive reading of Kerouac’s prose and engages with his negotiations of race, gender, spirituality and origins within the framework of post-war America’s accelerated culture. -

Beatnik Buddhism in Jack Kerouac's the Dharma Bums

Beatnik Buddhism in Jack Kerouac’s The Dharma Bums A talk to the White Heron Sangha, October 6, 2013 I was introduced to the writings of Jack Kerouac by a trumpet-player friend in high school who gave me a copy of On the Road just after it came out in 1957. But though I’d already done some hitchhiking around New England and hung out in Greenwich Village on Friday nights, I was put off by the book’s frenetic style and its praise of aimless, restless travel. Twelve years later, in 1969, I encountered The Dharma Bums, Kerouac’s second most popular book, while selecting works to place on the syllabus of a class at Columbia University I called “Pastoral and Utopia, Visionary Conceptions of the Good Life.” This book’s triumphant celebration of free love, wilderness adventures, bohemian companionship, and Buddhist meditation made a perfect fit. Forty four years later, while looking for a topic for a Sangha talk to follow up on the one about Thoreau’s Buddhism I offered last Spring, I picked The Dharma Bums in order to consider how my perspective on the novel and its Buddhist themes might have changed in the meantime. I was encouraged upon reading the first page, where San Luis Obispo is mentioned as a stopover on the train-hopping circuit between L.A. and San Francisco. I remembered a 2009 New Times article revealing that Kerouac lived in this town for several months during 1943 while he worked as a brakeman on the Union Pacific Railroad and that he stayed in a rooming house on Santa Barbara Street now known as The Establishment.