Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans"

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

The Spirit of the Living Creatures Was in the Wheels -- Ezekiel 1:21

The spirit of the living creatures was in the wheels -- Ezekiel 1:21 "Wheels Within Wheels deepens the musical experience created at Congregation Bet Haverim by lifting the veil between the ordinary and the sacred, so that our earthy expression of musical holiness connects with the celestial resonance of the universal. Like Ezekiel’s mystical vision, the spirals of harmonies, voices and instruments evoke contemplation, awe and celebration. At times Wheels Within Wheels will transport you to an intimate experience with your innermost self, and at other times it will convey a profound connection with the world around you." -- Rabbi Joshua Lesser THE MUSICIANS OF CONGREGATION BET HAVERIM Chorus Soprano: Nefesh Chaya, Sara Dardik, Julie Fishman, Nancy Gerber, Joy Goodman, Ellie McGraw, Theresa Prestwood, Rina Rosenberg, Faith Russler, Sandi Schein Alto: Jesse Harris Bathrick, Elke Davidson, Gayanne Geurin, Kim Goldsmith, Rebecca Green, Carrie Hausman, Alix Laing, Rebecca Leary Safon, AnnaLaura Scheer, Valerie Singer, Linda Weiskoff, Valerie Wolpe, McKenzie Wren Tenor: Ned Bridges, Brad Davidorf, Faye Dresner, Henry Farber, Alan Hymowitz, Lynne Norton Bass: Dan Arnold, Gregg Bedol, David Borthwick, Gary Falcon, Bill Laing, Bill Witherspoon, Howard Winer Band Will Robertson, guitar, keyboards; Natalie Stahl, clarinet, saxophone; Sarah Zaslaw, violin, viola; Reuben Haller, mandolin; Jordan Dayan, bass, electric bass; Mike Zimmerman, drum kit, percussion; Henry Farber and Gayanne Geurin, percussion; with Matthew Kaminski, accordion Strings Sarah Zaslaw and Benjamin Reiss, violin; David Borthwick, viola; Ruth Einstein, cello; Will Robertson, double bass Children’s Choir and CBH Community School Chorus director: Will Robertson Music director: Gayanne Geurin Thank You It takes a shul to raise a recording. -

The ONE and ONLY Ivan

KATHERINE APPLEGATE The ONE AND ONLY Ivan illustrations by Patricia Castelao Dedication for Julia Epigraph It is never too late to be what you might have been. —George Eliot Glossary chest beat: repeated slapping of the chest with one or both hands in order to generate a loud sound (sometimes used by gorillas as a threat display to intimidate an opponent) domain: territory the Grunt: snorting, piglike noise made by gorilla parents to express annoyance me-ball: dried excrement thrown at observers 9,855 days (example): While gorillas in the wild typically gauge the passing of time based on seasons or food availability, Ivan has adopted a tally of days. (9,855 days is equal to twenty-seven years.) Not-Tag: stuffed toy gorilla silverback (also, less frequently, grayboss): an adult male over twelve years old with an area of silver hair on his back. The silverback is a figure of authority, responsible for protecting his family. slimy chimp (slang; offensive): a human (refers to sweat on hairless skin) vining: casual play (a reference to vine swinging) Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Glossary hello names patience how I look the exit 8 big top mall and video arcade the littlest big top on earth gone artists shapes in clouds imagination the loneliest gorilla in the world tv the nature show stella stella’s trunk a plan bob wild picasso three visitors my visitors return sorry julia drawing bob bob and julia mack not sleepy the beetle change guessing jambo lucky arrival stella helps old news tricks introductions stella and ruby home -

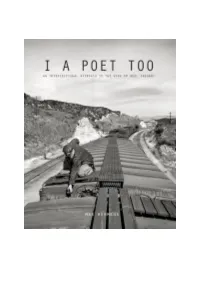

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

WHAT USE IS MUSIC in an OCEAN of SOUND? Towards an Object-Orientated Arts Practice

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Oxford Brookes University: RADAR WHAT USE IS MUSIC IN AN OCEAN OF SOUND? Towards an object-orientated arts practice AUSTIN SHERLAW-JOHNSON OXFORD BROOKES UNIVERSITY Submitted for PhD DECEMBER 2016 Contents Declaration 5 Abstract 7 Preface 9 1 Running South in as Straight a Line as Possible 12 2.1 Running is Better than Walking 18 2.2 What You See Is What You Get 22 3 Filling (and Emptying) Musical Spaces 28 4.1 On the Superficial Reading of Art Objects 36 4.2 Exhibiting Boxes 40 5 Making Sounds Happen is More Important than Careful Listening 48 6.1 Little or No Input 59 6.2 What Use is Art if it is No Different from Life? 63 7 A Short Ride in a Fast Machine 72 Conclusion 79 Chronological List of Selected Works 82 Bibliography 84 Picture Credits 91 Declaration I declare that the work contained in this thesis has not been submitted for any other award and that it is all my own work. Name: Austin Sherlaw-Johnson Signature: Date: 23/01/18 Abstract What Use is Music in an Ocean of Sound? is a reflective statement upon a body of artistic work created over approximately five years. This work, which I will refer to as "object- orientated", was specifically carried out to find out how I might fill artistic spaces with art objects that do not rely upon expanded notions of art or music nor upon explanations as to their meaning undertaken after the fact of the moment of encounter with them. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, a Novel on His Website, the Author Places It in the Public Domain

THE MARVEL UNIVERSE origin stories a NOVEL by BRUCE WAGNER Press Send Press 1 By releasing The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, A Novel on his website, the author places it in the public domain. All or part of the work may be excerpted without the author’s permission. The same applies to any iteration or adaption of the novel in all media. It is the author’s wish that the original text remains unaltered. In any event, The Marvel Universe: Origin Stories, A Novel will live in its intended, unexpurgated form at brucewagner.la – those seeking veracity can find it there. 2 for Jamie Rose 3 Nothing exists; even if something does exist, nothing can be known about it; and even if something can be known about it, knowledge of it can't be communicated to others. —Gorgias 4 And you, you ridiculous people, you expect me to help you. —Denis Johnson 5 Book One The New Mutants be careless what you wish for 6 “Now must we sing and sing the best we can, But first you must be told our character: Convicted cowards all, by kindred slain “Or driven from home and left to die in fear.” They sang, but had nor human tunes nor words, Though all was done in common as before; They had changed their throats and had the throats of birds. —WB Yeats 7 some years ago 8 Metamorphosis 9 A L I N E L L Oh, Diary! My Insta followers jumped 23,000 the morning I posted an Avedon-inspired black-and-white selfie/mugshot with the caption: Okay, lovebugs, here’s the thing—I have ALS, but it doesn’t have me (not just yet). -

Moloch's Children: Monstrous Techno-Capitalism in North American Popular Fiction

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 10-17-2019 2:00 PM Moloch's Children: Monstrous Techno-Capitalism in North American Popular Fiction Alexandre Desbiens-Brassard The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Randall, Marilyn The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Alexandre Desbiens-Brassard 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons Recommended Citation Desbiens-Brassard, Alexandre, "Moloch's Children: Monstrous Techno-Capitalism in North American Popular Fiction" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6581. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6581 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract Deriving from the Latin monere (to warn), monsters are at their very core warnings against the horrors that lurk in the shadows of our present and the mists of our future – in this case, the horrors of techno-capitalism (i.e., the conjunction of scientific modes of research and capitalist modes of production). This thesis reveals the ideological mechanisms that animate “techno-capitalist” monster narratives through close readings of 7 novels and 3 films from Canada and the United States in both English and French and released between 1979 and 2016. All texts are linked by shared themes, narrative tropes, and a North American origin. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation

MARIA BLOSHTEYN Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation American literary history is rich with heroes of counterculture, maverick writers and poets who were rejected by the bulk of their contemporaries but inspired a cult-like following among a few devotees. The phenomenon of Beat Generation writers and poets, however, is unique in twentieth-century American letters precisely because they managed to go from marginal underground classics of the 1950s to the official voice of dissent and cultural opposition of the 1960s, a force to be reckoned with. Their books were adopted by hippies and flower children, their poems chanted at sit-ins, their lives faithfully imitated by a whole generation of young baby boomers. Their antiauthoritarian ethos along with their belief in the brotherhood of mankind were the starting point of a whole movement that gave the United States such social and cultural watersheds as Woodstock and the Summer of Love, the Chicago Riots and the Marches on Washington. The suggestion that Dostoevsky had anything to do with the American Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and street rioting in American urban centres might seem at first to be far-fetched. It is, however, a powerful testimony to Dostoevsky’s profound impact on twentieth-century American literature and culture that the first Beats saw themselves as followers of Dostoevsky and established their personal and literary union (and, as it were, the entire Beat movement) on the foundation of their shared belief in the primacy of Dostoevsky and his novels. Evidence of Dostoevsky’s impact on such key writers and poets of the Beat Generation as Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), and William Burroughs (1914-1997) is found in an almost embarrassing profusion: scattered throughout their essays, related in their correspondence, broadly hinted at and sometimes explicitly indicated in their novels and poems. -

Resistance Through Space: a Comparative Study of Narrative and Space in Naked Lunch and on the Road

Department of English Resistance Through Space: A Comparative Study of Narrative and Space in Naked Lunch and On the Road Luca Pirro Bachelor Degree Project Literature Fall, 2016 Supervisor: Frida Beckman Abstract This essay compares two influential novels from the Beat era, William Burroughs’ Naked Lunch and Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, and how they use the spatial dimension of writing as a tool for resistance. The spatiality of Kerouac’s travel narrative is compared to the spatiality of Burroughs cut-up narrative, and the spaces of cities and the road are analyzed. I argue that On the Road is an attempt at a spiritual escape from Western dogmatism—dramatized through the means of a spatial journey—whilst Naked Lunch is attempting an escape from “control”, mediated through the means of a spatial destabilization in the narrative. In trying to define the term “control” used by Burroughs, I look at Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, as well as other sources, in order to determine which mechanisms of society that are being reacted against in these novels. The historical context of these two Beat writers as situated in the American postwar era is also considered – a context which is examined in relation to the concept of normality. Keywords: Beat; space; resistance; control; cut-up; travel narrative Pirro 1 “[T]he ‘human condition’ is often one of disorientation, where our experience of being-in- the-world frequently resembles being lost.” (Tally 43) The spaces around us can be either confining or liberating. A classroom, one’s home, the town square or one’s home country – these are all spaces that, depending on who you ask (and when), may function as a safe refuge or as a prison.