Female Representation in the Beat Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Writings by of the Beat Generation Edited by Richard Peabody

a edited by richard peabody writings by women of the beat generation eat BOOKS Contents Introduction 1 Mimi Albert from The Second Story Man 4 Carol Berge tessa's song 12 Pavane for the White Queen 15 Chant for Half the World 18 Etching 21 Carolyn Cassady from Off the Road: My Years with Cassady, Kerouac, and Ginsberg 22 Elise Cowen "At the acting class" 27 "Dear God of the bent trees of Fifth Avenue" 27 "Death I'm coming" 28 "I took the skin of corpses" 29 "I wanted a cunt of golden pleasure" 30 "If it weren't for love I'd snooze all day" 31 "The sound now in the street is the echo of a long" 31 "Trust yourself—but not too far" 32 LeoSkir Elise Cowen: A Brief Memoir of the Fifties 33 Diane di Prima The Quarrel 46 Requiem 47 Minor Arcana 48 The Window 49 For Zella, Painting 50 from Memoirs of a Beatnik 51 Brenda Frazer Breaking out of D.C. (1959) 60 Sandra Hochman Farewell Poems 65 About My Life at That Time 66 Postscript 66 Julian 67 The Seed 68 Cancer 69 Burning with Mist 70 There Are No Limits to Mv Svstem 71 Joyce Johnson from Minor Characters 72 Contents I vii Kay Johnson Proximity 80 poems from paris 84 Hettie Jones from How I Became Hettie Jones 88 Lenore Kandel First They Slaughtered the Angels 100 Love-Lust Poem 103 Junk/Angel 105 Blues for Sister Sally 106 Eileen Kaufman from Who Wouldn't Walk with Tigers 108 Frankie "Edie" from You'll Be Okay 115 Kerouac-Parker Jan Kerouac from Baby Driver 124 from Trainsong 132 Joan Haverty Kerouac from Nobody's Wife 134 Joanne Kyger Tapestry 140 "Waiting again" 140 "They are constructing a -

Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood

University of Central Florida STARS Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 2017 Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood Kevin Mercer University of Central Florida Part of the History Commons Find similar works at: https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd University of Central Florida Libraries http://library.ucf.edu This Masters Thesis (Open Access) is brought to you for free and open access by STARS. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019 by an authorized administrator of STARS. For more information, please contact [email protected]. STARS Citation Mercer, Kevin, "Hippieland: Bohemian Space and Countercultural Place in San Francisco's Haight-Ashbury Neighborhood" (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations, 2004-2019. 5540. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/5540 HIPPIELAND: BOHEMIAN SPACE AND COUNTERCULTURAL PLACE IN SAN FRANCISCO’S HAIGHT-ASHBURY NEIGHBORHOOD by KEVIN MITCHELL MERCER B.A. University of Central Florida, 2012 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of History in the College of Arts and Humanities at the University of Central Florida Orlando, Florida Summer Term 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis examines the birth of the late 1960s counterculture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury neighborhood. Surveying the area through a lens of geographic place and space, this research will look at the historical factors that led to the rise of a counterculture here. To contextualize this development, it is necessary to examine the development of a cosmopolitan neighborhood after World War II that was multicultural and bohemian into something culturally unique. -

The Sixties Counterculture and Public Space, 1964--1967

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Spring 2003 "Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967 Jill Katherine Silos University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Silos, Jill Katherine, ""Everybody get together": The sixties counterculture and public space, 1964--1967" (2003). Doctoral Dissertations. 170. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/170 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 12-2013 "Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 Kayla D. Meyers College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Kayla D., ""Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 767. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/767 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull”: Deconstructing The Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Kayla Danielle Meyers Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Charles McGovern, Director ________________________________________ Arthur Knight ________________________________________ Marc Raphael Williamsburg, VA December 3, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction: The Poet is Holy.........................................................................................................2 -

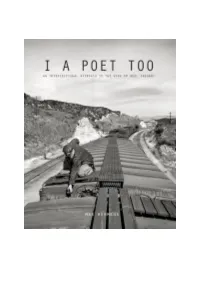

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

1 Before London Started Swinging: Representing the British Beatniks David Buckingham This Essay Is Part of a Larger Project

Before London started swinging: representing the British beatniks David Buckingham This essay is part of a larger project, Growing Up Modern: Childhood, Youth and Popular Culture Since 1945. More information about the project, and illustrated versions of all the essays can be found at: https://davidbuckingham.net/growing-up-modern/. In his autobiography, Personal Copy, the journalist and broadcaster Ray Gosling describes a feeling of imminent change that was shared by many young people at the very end of the 1950s: There was just this feeling… that we were important, that something was going to happen. How, and in what direction, we didn’t know. And we didn’t much care. It was a very, very, very odd feeling, but we felt it. Gosling himself came from a frugal working-class background in the provincial English city of Northampton. In 1959, he dropped out of university and set up a youth centre in Leicester that was run autonomously by a committee of young people. The academic Richard Hoggart – the author of The Uses of Literacy, who was soon to become the founding director of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies (CCCS) at Birmingham University – was on his management committee. Although Gosling’s youth centre collapsed, he developed the argument for youth-led welfare provision in a pamphlet for the Fabian Society; and he went on to build a career as a writer and public speaker, offering an insider’s perspective on the emerging youth culture of the time. He became associated with the New Left, and began to mix in the more cosmopolitan culture of London’s coffee bars, making friends with Stuart Hall (then the editor of the New Left Review) and the novelist Colin MacInnes, whom he described as his ‘mentor’. -

Research for the Worcester Writers IQP “City

Kevin Curley Worcester Writers IQP 2009-2010 Worcester Polytechnic Institute Interdisciplinary Qualifying Project Summery: Research for the Worcester Writers IQP “City of Words” Website 1 Abstract The City of Words IPQ Project group is with the goal of creating a web site featuring writers associated with Worcester. It is based on the web site Worcester Area Writers, which was created by WPI faculty and students some years ago. We are placing heavy emphasis on bringing living writers to the new site, creating a multi-media platform that includes videos of writers reading their works, interviews, audio, and photographs of places in Worcester connected with their work. The group continually seeks creative and original ways to display the site‟s content. Students are required to produce these materials as well as write biographies and critical analyses of the writers for which they are responsible. 2 Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 IQP Research Methods....................................................................................................................................... 5 Abbie Hoffman Biographical Writing .................................................................................................................. 7 Abbie Hoffman Analytical Composition ............................................................................................................ 14 References ...................................................................................................................................................... -

National FUTURE FARMER

The National \Oj:c .V'A uture «^ 'Vihlished b Future Farmers of America Fel)ruarv-Marcli 1961 "don't sacrifice the PERMAMEMT on the altar of the IMMEDMtE should make the best possible preparation for a life of effective service To neglect or postpone your for his Lord. education for some present inducement, whether it be a job that '^^pays good money," a desire to ^^gef married right now," or anything else, is to fail to put first things first. If you sincerely want your life to count for God, the can train and equip you for successful service. THE TIME TO GET YOUR BOB JONES UNIVERSITY TRAINING IS NOW. Music, speech, and arl without additional BOB JONES cost above regular academic tuition. Institute of Christian Service, Academy, UNIVERSITY and seventh and eighth grades in connection. GREENVILLE, SOUTH CAROLINA Grdiliitilt' Sriiool of Reliix'ion Gnuludte School of Fine Arts Rancher David James of Joplir, Montana Farmers you look to as leaders look to Firestone for farm tires Farmers around Joi^lin, Montana, look to David James as an energetic pace- setter. When it comes to producing huge grain yields in the rugged northern-border country, Mr. James really knows his business. And for this he's recognized as one of Liberty County's leading ranchers. He also finds time to play a leading role in vital state affairs. Mr. James's brand of success calls for good farming practices and the right equipment to keep thousands of acres producing at peak efficiency. From long experience he knows he can always depend on Firestone tires. -

From Beat to Bad Connections: Joyce Johnson's (Feminist) Response To

Faculteit Letteren & Wijsbegeerte Valérie Partoens From Beat to Bad Connections: Joyce Johnson’s (Feminist) Response to Kerouac’s On the Road Masterproef voorgedragen tot het behalen van de graad van Master in de American Studies 2014 Promotor Prof. Isabel Meuret Vakgroep Letterkunde Expression of thanks First of all, I would not have been able to complete this dissertation without the time and guidance of my supervisor Isabel Meuret. In addition, I would also like to thank the Master Program of American Studies and its team of professors for giving me the opportunity to gain more knowledge about a field of studies in which I have always been extremely interested. Likewise, I would also want to express my gratitude towards my classmates, of whom many now have become close friends, for their friendship and for their help during this year. Evidently, I would not be able to finish this thesis and this year of higher education without the support of my family and friends, who always believed in me even when I did not. Last but not least, I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Joyce Johnson, who took the time to personally discuss her novel Bad Connections and as a result gave me the opportunity to gain a more comprehensive insight into the particular setting of the novel and her life within the Beat movement. 2 Table of Contents EXPRESSION OF THANKS ..................................................................................................2 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................4 -

Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans"

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1997 Going Nowhere Fast: The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans" Scott Patrick Moyers College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons, and the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Moyers, Scott Patrick, "Going Nowhere Fast: The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov's "Lolita" and Robert Frank's "The Americans"" (1997). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626114. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-a0k8-dq26 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Going Nowhere Fast The Car, the Highway and American Identity in Vladimir Nabokov’sLolita and Robert Frank’sThe Americans A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Scott Moyers 1997 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, July 1997 Colleen Kennedy -

On the Borderline of Expectation and Desire in Joyce Johnson's

Archived thesis/research paper/faculty publication from the University of North Carolina at Asheville’s NC DOCKS Institutional Repository: http://libres.uncg.edu/ir/unca/ “Mad to Be Saved”: On the Borderline of Expectation and Desire in Joyce Johnson’s Come and Join the Dance Senior Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For a Degree Bachelor of Arts with A Major in Literature at The University of North Carolina at Asheville Spring 2016 By Jessica Nicole Pringle ____________________ Thesis Director Dr. Evan Gurney ____________________ Thesis Advisor Dr. Lori Horvitz Pringle 1 The year is 1955 in America the Great. Dwight Eisenhower is president, the Battle of Dienbienphu is underway, and Allen Ginsberg is reading his first draft of “Howl” at the Gallery Six. The Seven Year Itch has hit the big screen, women are stationed in their houses, and the economy has been struck by a momentous deflation. Vagabonds are scouring the states, their right thumbs in the air, while the abomunists1 perform their 9-5’s in the center of an emergent poetic riff-raff. The 1950s was jazz, was finger-snapping stanzas; it was the year of the creative delinquent. The 1950s was The Beat Generation, and a fraction of that beat feeling can be attributed to 1950’s America being wrought with strict stereotypical roles for men and women, which produced alarming consequences. To give context, men were oftentimes the ‘breadwinners,’ and were afforded the opportunities to establish careers, to explore the world in a multitude of ways, and to realize the capacity of their talents and traits, all which worked together in cultivating a sense of identity (Lindsey 17).