On the Road Jack Kerouac’S Epic Autoethnography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Importance of Mobilty in Jack Kerouac's on the Road And

SOBİAD Mart 2015 Onur KAYA IMPORTANCE OF MOBILTY IN JACK KEROUAC’S ON THE ROAD AND DENNIS HOPPER’S EASY RIDER Arş. Gör. Onur KAYA Abstract Journey as a mobility in 1950s and 1960s of the United States of America showed itself in the works of authors and directors of the films. Among them, Jack Kerouack’s On The Road (1955) and Dennis Hopper’s Easy Rider (1969) are significant works. Analysing both works will put forth representation of mobility in America and the period. For the method, mobility notion will be emphasized. The mobility notion in works and representation of its effects on people, period will be analyzed. Comparison of representation of mobility in two works will be done. Finally, the study will reveal the importance of mobility in the American society. Key Words: Beats, 50s, 60s, Mobility, Road JACK KEROUAC’IN ON THE ROAD VE DENNIS HOPPER’IN EASY RIDER YAPITLARINDA HAREKETLİLİĞİN ÖNEMİ Öz Yolculuk bir hareketlilik olarak Amerika Birleşik Devletlerinin 1950ler ve 1960larında yazarlarla film yönetmenlerinin eserlerinde kendisini göstermiştir. Bunlar içerisinde Jack Kerouack’ın On The Road (1955) ve Dennis Hopper’ın Easy Rider (1969) eserleri önemli yapıtlardır. Her iki eserin incelenmesi o dönemde ve Amerika’da hareketliliğin temsilini ortaya koyacaktır. Metot olarak hareketlilik kavramı irdelenecektir. Eserlerdeki hareketlilik kavramı ve onun insanlarla dönem üzerindeki etkileri analiz edilecektir. Her iki eserdeki hareketlililiğin temsilinin karşılaştırılması yapılacaktır. Sonuç olarak çalışma Amerikan toplumundaki hareketliliğin -

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

Jack Kerouac and the Influence Of

JACK KEROUAC AND THE INFLUENCE OF BEBOP by David Kastin* _________________________________________________________ [This is an excerpt from David Kastin’s book Nica’s Dream: The Life and Legend of the Jazz Baroness, pages 58-62.] ike many members of his generation, Jack Kerouac had been enthralled by the dynamic rhythms of the swing era big bands he listened to on the radio as a L teenager. Of course, what he heard was the result of the same racial segregation that was imposed on most areas of American life. The national radio networks, as well as most of the independent local stations, were vigilant in protecting the homes of the dominant culture against the intrusion of any and all soundwaves of African American origin. That left a lineup of all-white big bands, ranging from "sweet" orchestras playing lush arrangements of popular songs to "hot" bands who provided a propulsive soundtrack for even the most fervent jitterbugs. Jack Kerouac: guided to the riches of African American culture… ________________________________________________________ *David Kastin is a music historian and educator who in 2011 was living in Brooklyn, New York. He was the author of the book I Hear America Singing: An Introduction to Popular Music, and a contributor to DownBeat, the Village Voice and the Da Capo Best Writing series. 1 After graduating from Lowell High School in 1939, Kerouac left the red-brick Massachusetts mill town for New York City, where he had been awarded a football scholarship to Columbia University. In order to bolster his academic credentials and put on a few pounds before his freshman season, Jack was encouraged to spend a year at Horace Mann, a Columbia-affiliated prep school popular with New York's middle-class intellectual elite. -

The 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation Jamie L. Rehlaender Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Cultural History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Rehlaender, Jamie L., "A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Jamie L. Rehlaender Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 201: History of the US Portland State University March 19, 2015 2 A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Allen Ginsberg’s first recitation of his poem Howl , on October 13, 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, ended in tears, both from himself and from members of the audience. “The people gasped and laughed and swayed,” One Six Gallery gatherer explained, “they were psychologically had, it was an orgiastic occasion.”1 Ironically, Ginsberg, upon initially writing Howl , had not intended for it to be a publicly shared piece, due in part to its sexual explicitness and personal references. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

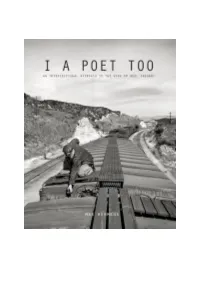

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

On the Road: the Original Scroll by Jack Kerouac

On the Road: The Original Scroll by Jack Kerouac A reproduction of Kerouac's original 1951 scroll draft of On the Road offers insight into the writer's thematic vision and narrative voice as influenced by the American literary, musical, and visual arts of the post-World War II period. Why you'll like it: Autobiographical. Frantic. Beat Generation. Unpolished. About the Author: Jack Kerouac was born in Lowell, Massachusetts, in 1922. His first novel, The Town and the City, was published in 1950. He considered all of his "true story novels," including On the Road, to be chapters of "one vast book," his autobiographical Legend of Duluoz. He died in St. Petersburg, Florida, in 1969 at the age of forty-seven. (Publisher Provided) Questions for Discussion 1. In the first sentence of the scroll Kerouac meets Cassady “not long after my father died.” In the novel, Sal meets Neal “not long after my wife and I split up”. Why do you think Kerouac changed the book's opening? What effect does this have on the novel? 2. How is On the Road written that is different from earlier, more traditional novels? What kind of effect does this have on traditional plot? Does the form help to express the themes of the novel? 3. To some readers, Cassady's role in the scroll version is less pronounced than Dean's in On the Road. Do you agree? 4. Is Dean a hero, a failure, or both? 5. What is Sal's idea of the West compared to his idea of the East? Does this change during the course of the novel? 6. -

A Comparison of the Works of Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac Jeffrey J

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Honors Theses University Honors Program 8-1994 "The rT iumph of the Individual Over Art": A Comparison of the Works of Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac Jeffrey J. Eustis Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/uhp_theses Recommended Citation Eustis, Jeffrey J., ""The rT iumph of the Individual Over Art": A Comparison of the Works of Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac" (1994). Honors Theses. Paper 203. This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the University Honors Program at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -' . "The Triumph of the Individual Over Art": A Comparison of the Works of Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac Jeffrey Eustis August 1994 Senior Thesis 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction 3 II . Theories of Writing 7 III. Miller and Kerouac: Misogynists? Sex Fiends? 18 IV. Conclusion 30 V. Bibliography 33 3 I. Introduction Henry Miller and Jack Kerouac had much in common with one another. One of their most unfortunate common traits was their lack of acceptance by the literary establishment. Both of them had unfair one-dimensional reputations which largely have remained intact, years after their deaths. For example, Miller was always seen as a writer of "dirty books," his early master pieces such as Tropic of Cancer being regarded by many as little more than the literary equivalent of a raunchy stag film. Kerouac was viewed by many critics, and much of the pUblic, as nothing more than a hard-drinking, hell-raising hoodlum transcribing the "hep" aphorisms of his "beatnik" friends. -

Allen Ginsberg Beat Memories

ALLEN GINSBERG BEAT MEMORIES Exhibition diChromA photography TECHNICAL DETAILS Contents 80 b&w photographs .Unframed Part of the photographs contains the original caption wrote by A.Ginsberg and signed. Size of Works From Photo Blooth size to 50x60cm Conditions Unframed Transport From Madrid Rental Conditions The borrower will be in charge of: -The transport from and to Madrid -The insurance, nail to nail -Travel and journey of the curator for the installation and opening Availability From September 2011 Contact Anne Morin [email protected] Herbert Huncke, 1950’s © Allen Ginsberg Jack Kerouac, 1953 Rebecca Ginsberg, my paternal grandmother, R.Frank photographing Allen Ginsberg for Collected Poems”1984 Paterson, New Jersey, 1953 diChroma photography Paseo de los Parques, 27-8B 28109 Alcobendas-Madrid-Spain www.dichroma-photography.com ALLEN GINSBERG BEAT MEMORIES "I do my sketching and observing with the camera." Allen Ginsberg, 1993 One of the most visionary writers of his generation and author of the celebrated poem Howl, Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997) was also a photographer. From 1953 until 1963 he made numerous, often exuberant portraits of himself and his friends, including the Beat writers William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac. Eager to capture "certain moments in eternity," as he wrote, he kept his camera by his side when he was at home or traveling around the world. For years Ginsberg's photographs languished among his papers. When he finally rediscovered them in the 1980s, he reprinted them, adding handwritten inscriptions Inspired by his earlier work, he also began to photograph again, recording longtime friends and new acquaintances.