Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

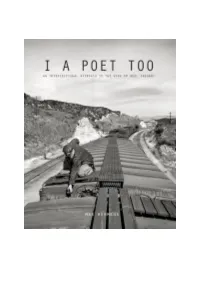

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

A History of Modern Drama

Krasner_bindex.indd 404 8/11/2011 5:01:22 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I Krasner_ffirs.indd i 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM Books by David Krasner An Actor’s Craft: The Art and Technique of Acting (2011) Theatre in Theory: An Anthology (editor, 2008) American Drama, 1945–2000: An Introduction (2006) Staging Philosophy: New Approaches to Theater, Performance, and Philosophy (coeditor with David Saltz, 2006) A Companion to Twentieth-Century American Drama (editor, 2005) A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama, and Performance, 1910–1927 (2002), 2002 Finalist for the Theatre Library Association’s George Freedley Memorial Award African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader (coeditor with Harry Elam, 2001), Recipient of the 2002 Errol Hill Award from the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) Method Acting Reconsidered: Theory, Practice, Future (editor, 2000) Resistance, Parody, and Double Consciousness in African American Theatre, 1895–1910 (1997), Recipient of the 1998 Errol Hill Award from ASTR See more descriptions at www.davidkrasner.com Krasner_ffirs.indd ii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I David Krasner A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Krasner_ffirs.indd iii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM This edition first published 2012 © 2012 David Krasner Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. -

The Importance of Neal Cassady in the Work of Jack Kerouac

BearWorks MSU Graduate Theses Spring 2016 The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac Sydney Anders Ingram As with any intellectual project, the content and views expressed in this thesis may be considered objectionable by some readers. However, this student-scholar’s work has been judged to have academic value by the student’s thesis committee members trained in the discipline. The content and views expressed in this thesis are those of the student-scholar and are not endorsed by Missouri State University, its Graduate College, or its employees. Follow this and additional works at: https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Ingram, Sydney Anders, "The Need For Neal: The Importance Of Neal Cassady In The Work Of Jack Kerouac" (2016). MSU Graduate Theses. 2368. https://bearworks.missouristate.edu/theses/2368 This article or document was made available through BearWorks, the institutional repository of Missouri State University. The work contained in it may be protected by copyright and require permission of the copyright holder for reuse or redistribution. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC A Masters Thesis Presented to The Graduate College of Missouri State University TEMPLATE In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts, English By Sydney Ingram May 2016 Copyright 2016 by Sydney Anders Ingram ii THE NEED FOR NEAL: THE IMPORTANCE OF NEAL CASSADY IN THE WORK OF JACK KEROUAC English Missouri State University, May 2016 Master of Arts Sydney Ingram ABSTRACT Neal Cassady has not been given enough credit for his role in the Beat Generation. -

Male View of Women in the Beat Generation

Fredrik Olsson (6 March 1979) A60 Term Paper Autumn 2005 Department of English Lund University Supervisor: Annika Hill Male view of women in the Beat Generation – A study of gender in Jack Kerouac’s On the Road INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................................................. 1 1. THE BEAT GENERATION ............................................................................................................................ 3 2. MALE BONDING AND MARGINALIZED WOMEN................................................................................. 4 3. WOMEN AND SOCIETY – GENDER PROBLEMS.................................................................................... 6 4. OBJECTIFICATION OF WOMEN ............................................................................................................... 9 THE MALE GAZE ................................................................................................................................................ 10 GETTING THE KICKS .......................................................................................................................................... 12 THE FEMALE BACKLASH .................................................................................................................................... 14 5. FROM BEATS TO FAMILY......................................................................................................................... 15 CONCLUSION................................................................................................................................................... -

Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation

MARIA BLOSHTEYN Dostoevsky and the Beat Generation American literary history is rich with heroes of counterculture, maverick writers and poets who were rejected by the bulk of their contemporaries but inspired a cult-like following among a few devotees. The phenomenon of Beat Generation writers and poets, however, is unique in twentieth-century American letters precisely because they managed to go from marginal underground classics of the 1950s to the official voice of dissent and cultural opposition of the 1960s, a force to be reckoned with. Their books were adopted by hippies and flower children, their poems chanted at sit-ins, their lives faithfully imitated by a whole generation of young baby boomers. Their antiauthoritarian ethos along with their belief in the brotherhood of mankind were the starting point of a whole movement that gave the United States such social and cultural watersheds as Woodstock and the Summer of Love, the Chicago Riots and the Marches on Washington. The suggestion that Dostoevsky had anything to do with the American Sexual Revolution of the 1960s and street rioting in American urban centres might seem at first to be far-fetched. It is, however, a powerful testimony to Dostoevsky’s profound impact on twentieth-century American literature and culture that the first Beats saw themselves as followers of Dostoevsky and established their personal and literary union (and, as it were, the entire Beat movement) on the foundation of their shared belief in the primacy of Dostoevsky and his novels. Evidence of Dostoevsky’s impact on such key writers and poets of the Beat Generation as Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), Jack Kerouac (1922-1969), and William Burroughs (1914-1997) is found in an almost embarrassing profusion: scattered throughout their essays, related in their correspondence, broadly hinted at and sometimes explicitly indicated in their novels and poems. -

Beat Memories: the Photographs of Allen Ginsberg at NYU’S Grey Art Gallery January 15–April 6, 2013

Contact: Alyson Cluck 212/998-6782 or [email protected] Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg At NYU’s Grey Art Gallery January 15–April 6, 2013 First major New York exhibition of Ginsberg’s photographs Spontaneous, uninhibited snapshots capture poet’s contemporaries; celebrate “the sacredness of the moment” through image and text New York City (September 28, 2012)—Compelling photographs taken by renowned 20th- century American poet Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997) of himself and his fellow Beat poets are the subject of the first scholarly exhibition and catalogue of these works. New York University’s Grey Art Gallery will present Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, which includes portraits of literary luminaries such as William S. Burroughs, Neal Cassady, Gregory Corso, and Jack Kerouac, on view from January 15 through April 6, 2013. Organized by the National Gallery of Art, Washington, and curated by senior curator of photographs Sarah Greenough, the exhibition features 94 black-and-white works—many accompanied by Ginsberg’s intimate, handwritten captions—that convey the spontaneity, freedom, and exuberant lifestyle of the Beat Generation. The presentation at the Grey Art Gallery will be supplemented by original manuscripts, typewritten poems, correspondence, drawings, and sketches produced by Ginsberg and the individuals he photographed. “We are pleased to host this exhibition of Ginsberg’s celebrated portraits,” notes Lynn Gumpert, director of the Grey Art Gallery. “Many were taken within walking distance of Greenwich Village, which holds countless favored Beat haunts. Exhibiting Beat Memories at the Grey Art Gallery displays these captivating works nearly next door to their original settings. -

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America

“With Imperious Eye”: Kerouac, Burroughs, and Ginsberg on the Road in South America Manuel Luis Martinez But invasion is the basis of fear: there’s no fear like invasion. -William S. Burroughs Barry Miles, biographer of both Allen Ginsberg and William S. Burroughs, gives a typical interpretation of the Beat phenomenon’s political significance: The group was more of a fraternity of spirit and at- titude than a literary movement, and their writings have little in common with each other; what they did have in common was a reaction to the ongoing car- nage of World War 11, the dropping of the A-bomb and the puritan small-mindedness that still char- acterized American life. They shared an interest in widening the area of consciousness, by whatever means available. (1992, 5) This quote is significant not only because of what Miles al- leges about the Beat writers, but also because of what he de- scribes as the Beat “reaction” to those postwar events commonly maintained as the most important. He suggests that a monolithic U.S. culture, in the throes of a puritanical con- servatism, was challenged by a group of heroic writers who countered its hypocrisy and blindness by “widening the area of consciousness.” The version of history that this view im- plies is troublesome for many reasons. First, it posits an axis Aztlan 23:l Spring 1998 33 Martinez of historical relations in which conservative arbiters of bour- geois culture are set against a subversive group that saves the decade by creating a liberating cultural movement, a move- ment that “widens”consciousness and presages the even more “liberating”countercultural movement of the 1960s. -

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters the Origins of the Psychedelic Movement Through the Lens of the Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test

Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters The Origins of the Psychedelic Movement Through the Lens of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test Eleonora De Crescenzo Coming Together or Coming Apart? Europe and the United States in the Sixties Intensive Seminar in Berlin, September 12-24, 2011 Professor Russel Duncan 14 October 2011 Eleonora De Crescenzo Ca' Foscari Venice University IP Berlin – John F.Kennedy Institut Freie Univertät Berlin Ken Kesey and the Merry Pranksters The Origins of the Psychedelic Movement Through the Lens of The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test In 1968 a phenomenon baffled the national imagination: the transformation of the "promising middle-class youth with all the advantages" into what was popularly known as "the hippie"1 The 1960s appear as one of the most culturally complex periods in American history. Nearly all social values were put into discussion, from the “separate but equal” policy to the family structure, from the woman’s role in society to US foreign policy in Vietnam. It would be naïve to argue that such change only came about thanks to political protest songs or the use of hallucinogenic drugs. Rather the process of growing awareness and dissatisfaction with the current society had been underway for a considerable amount of time, and was simply accelerated by an increasing generational divide, a symptom of the coming of age of the baby boomers. What remains undeniable is the influence of what started as youth protests and became the counterculture movement had on reshaping American values, an effect which continues to be felt today. The myriad of differing movements which made up 60s culture merged together in such a way that today it can be difficult to distinguish them.