Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

R0693-05.Pdf

I' i\ FILE NO .._O;:..=5:....:::1..;::..62;;;;..4:..- _ RESOLUTION NO. ----------------~ 1 [Howl Week.] 2 3 Resolution declaring the week of October 2-9 Howl Week in the City and County of San 4 Francisco to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the first reading of Allen Ginsberg's 5 classic American poem about the Beat Generation. 6 7 WHEREAS, Allen Ginsberg wrote Howl in San Francisco, 50 years ago in 1955; and 8 ! WHEREAS, Mr. Ginsberg read Howl for the first time at the Six Gallery on Fillmore 9 I Street in San Francisco on October 7, 1955; and 10 WHEREAS, The Six Gallery reading marked the birth of the Beat Generation and the 11 I start not only of Mr. Ginsberg's career, but also of the poetry careers of Michael McClure, 12 Gary Snyder, Jack Kerouac, Philip Whalen; and 13 14 WHEREAS, Howl was published by Lawrence Ferlinghetti at City Lights and has sold 15 nearly one million copies in the Pocket Poets Series; and 16 WHEREAS, Howl rejuvenated American poetry and marked the start of an American 17 Cultural Revolution; and 18 WHEREAS, The City and County of San Francisco is proud to call Allen Ginsberg one 19 of its most beloved poets and Howl one of its signature poems; and, 20 WHEREAS, October 7,2005 will mark the 50th anniversary of the first reading of 21 HOWL; and 22 WHEREAS, Supervisor Michela Alioto-Pier will dedicate a plaque on October 7,2005 23 at the site of Six Gallery; now, therefore, be it 24 25 SUPERVISOR PESKIN BOARD OF SUPERVISORS Page 1 9/20/2005 \\bdusupu01.svr\data\graups\pElskin\iagislatiarlire.soll.ltrons\2005\!lo\l'lf week 9.20,05.6(J-(; 1 RESOLVED, That the San Francisco Board of Supervisors declares the week of 2 October 2-9 Howl Week to commemorate the 50th anniversary of this classic of 20th century 3 American literature. -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies At

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies at 101 An unapologetic proponent of “poetry as insurgent art,” he was also a publisher and the owner of the celebrated San Francisco bookstore City Lights. By Jesse McKinley Feb. 23, 2021 Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a poet, publisher and political iconoclast who inspired and nurtured generations of San Francisco artists and writers from City Lights, his famed bookstore, died on Monday at his home in San Francisco. He was 101. The cause was interstitial lung disease, his daughter, Julie Sasser, said. The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.) While older and not a practitioner of their freewheeling personal style, Mr. Ferlinghetti befriended, published and championed many of the major Beat poets, among them Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Michael McClure, who died in May. His connection to their work was exemplified — and cemented — in 1956 with his publication of Ginsberg’s most famous poem, the ribald and revolutionary “Howl,” an act that led to Mr. Ferlinghetti’s arrest on charges of “willfully and lewdly” printing “indecent writings.” In a significant First Amendment decision, he was acquitted, and “Howl” became one of the 20th century’s best-known poems. -

The 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation Jamie L. Rehlaender Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Cultural History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Rehlaender, Jamie L., "A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Jamie L. Rehlaender Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 201: History of the US Portland State University March 19, 2015 2 A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Allen Ginsberg’s first recitation of his poem Howl , on October 13, 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, ended in tears, both from himself and from members of the audience. “The people gasped and laughed and swayed,” One Six Gallery gatherer explained, “they were psychologically had, it was an orgiastic occasion.”1 Ironically, Ginsberg, upon initially writing Howl , had not intended for it to be a publicly shared piece, due in part to its sexual explicitness and personal references. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 12-2013 "Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 Kayla D. Meyers College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Meyers, Kayla D., ""Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull": Deconstructing the Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957" (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 767. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/767 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Obscene Odes on the Windows of the Skull”: Deconstructing The Memory of the Howl Trial of 1957 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in American Studies from The College of William and Mary by Kayla Danielle Meyers Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Charles McGovern, Director ________________________________________ Arthur Knight ________________________________________ Marc Raphael Williamsburg, VA December 3, 2013 Table of Contents Introduction: The Poet is Holy.........................................................................................................2 -

Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation

PALACKÝ UNIVERSITY OLOMOUC FACULTY OF ARTS Department of English and American Studies Veronika Nováková Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation Bachelor Thesis Thesis Supervisor: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 UNIVERZITA PALACKÉHO V OLOMOUCI FILOZOFICKÁ FAKULTA Katedra anglistiky a amerikanistiky Veronika Nováková Neal Cassady a jeho vliv na beat generation Bakalářská práce Vedoucí práce: PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. Olomouc 2016 Prohlašuji, že jsem bakalářskou práci na téma "Neal Cassady and His Influence on the Beat Generation" vypracovala samostatně pod odborným dohledem vedoucího práce a uvedla jsem všechny použité podklady a literaturu. V ...................... dne...................... Podpis ............................ Acknowledgements I would like to express my gratitude to PhDr. Matthew Sweney, Ph.D. for supervising my thesis and for his help. Table of contents Table of contents.......................................................................................................................6 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................7 2. The Real Neal Cassady ......................................................................................................9 2.1. Youth ........................................................................................................................9 2.2. Marriages ............................................................................................................... -

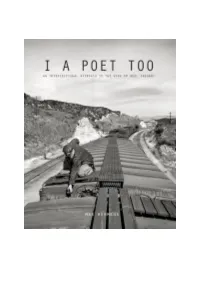

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

A History of Modern Drama

Krasner_bindex.indd 404 8/11/2011 5:01:22 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I Krasner_ffirs.indd i 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM Books by David Krasner An Actor’s Craft: The Art and Technique of Acting (2011) Theatre in Theory: An Anthology (editor, 2008) American Drama, 1945–2000: An Introduction (2006) Staging Philosophy: New Approaches to Theater, Performance, and Philosophy (coeditor with David Saltz, 2006) A Companion to Twentieth-Century American Drama (editor, 2005) A Beautiful Pageant: African American Theatre, Drama, and Performance, 1910–1927 (2002), 2002 Finalist for the Theatre Library Association’s George Freedley Memorial Award African American Performance and Theater History: A Critical Reader (coeditor with Harry Elam, 2001), Recipient of the 2002 Errol Hill Award from the American Society for Theatre Research (ASTR) Method Acting Reconsidered: Theory, Practice, Future (editor, 2000) Resistance, Parody, and Double Consciousness in African American Theatre, 1895–1910 (1997), Recipient of the 1998 Errol Hill Award from ASTR See more descriptions at www.davidkrasner.com Krasner_ffirs.indd ii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM A History of Modern Drama Volume I David Krasner A John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., Publication Krasner_ffirs.indd iii 8/12/2011 12:32:19 PM This edition first published 2012 © 2012 David Krasner Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientific, Technical, and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered Office John Wiley & Sons Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial Offices 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK For details of our global editorial offices, for customer services, and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell. -

Beat Generation and Postmodernism: Deconstructing the Narratives of America

2015 Beat Generation and Postmodernism: Deconstructing the Narratives of America Nicolas Deskos 10623272 MA Literary Studies: English Literature and Culture Supervisor: Dr Roger Eaton University of Amsterdam Contents Introduction 3 The American Dream 3 The Beat Generation 5 Postmodernism 8 Outline 9 Chapter 1: On the Road to a Postmodern Identity 11 Promise of the Road and Its Reality 12 What it Means to Be American 15 Searching for a Transcendent Identity 17 Chapter 2: Deconstructing Burroughs’ ‘Meaningless Mosaic’ 22 Language as a System of Control 23 Metafiction in Naked Lunch 27 Chapter 3: Ginsberg’s Mythical Heroes 32 Fragmentation of the Self 34 Heroes of the Past 39 Conclusion 43 Works Cited 47 2 Introduction This research aims to reinterpret and recontextualise the principal Beat writers – Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs – from the theoretical perspective of postmodernism. I aim to go beyond the traditional interpretation of the Beat Generation as a countercultural, counterhegemonic movement and challenge the “binary opposition between the establishment culture and a dissenting counterculture” (Martinez 7). Through the interpretative paradigm of postmodernism, I want to show that the Beat writers were concerned with the tension between the myths of America and its reality, appropriating one’s identity in the face of a dominant culture, and questions surrounding being, existence and reality. In doing so, I will locate their texts within the discourses of the mainstream as opposed to at its margins. Thus, I will argue that Burroughs, Kerouac and Ginsberg deconstruct, in their own ways, the official and mythical narratives of America, particularly the narrative on which the country is built: the American Dream.