America Singing Loud: Shifting Representations of American National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

What Is Genius of the Kazakh Poet Abay Kunanbayuly by Rashida

Shahanova Rozalinda Ashirbayevna Professor Head Department of the Philological Specialties Institute of Doctoral Studies Akademic of the International Academy of the Pedagogical Educational Sciences Almaty, Kazakhstan Shokanova Rashida Visiting Professor, Kazakh Language Jamia Millia Islamia New Delhi [email protected] What is genius of the Kazakh poet Abay Kunanbayuly? This article is about the great poet, philosopher, thinker, composer, educator of Kazakh people in the nineteenth century AbayKunanbay. Depite nor the era of colonial oppression, nor feudal-bourgeois system with all its shortcomings, when spread rot and humiliated people, as well as hid in prison, he was able - in spite of all the abominations being and destiny - to raise an unprecedented height resistance of the national spirit, singing and introducing into the consciousness of their fellow tenacity and boldness instead cowardice, focus, instead of a loss, the pursuit of knowledge, rather than ignorance and miserable careerism The acts instead Abay Kunanbay was born (July 29) August 10, 1845 in Chingiz Mountains Semipalatinsk region, in the family of a feudal lord Kunanbai Uskenbaev. His family was aristocratic, that is why Abay received a broad education. He attended a madrassa - Islamic school, is a both a high school and seminary. In addition, Abay was a disciple of the ordinary Russian school.The true figure, genuinely caring about his people, seeking and finding the way to new vertices. Today the name of Abay for many people on all continents should flush with the names of Shakespeare, Goethe, Pushkin and Moliere. Abay is the founder of Kazakh written literature. In the history of Kazakh literature Abay took pride of place, enriching the Kazakh versification new dimensions and rhymes. -

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (Guest Post)*

“Howl”—Allen Ginsberg (1959) Added to the National Registry: 2006 Essay by David Wills (guest post)* Allen Ginsberg, c. 1959 The Poem That Changed America It is hard nowadays to imagine a poem having the sort of impact that Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl” had after its publication in 1956. It was a seismic event on the landscape of Western culture, shaping the counterculture and influencing artists for generations to come. Even now, more than 60 years later, its opening line is perhaps the most recognizable in American literature: “I saw the best minds of my generation destroyed by madness…” Certainly, in the 20h century, only T.S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” can rival Ginsberg’s masterpiece in terms of literary significance, and even then, it is less frequently imitated. If imitation is the highest form of flattery, then Allen Ginsberg must be the most revered writer since Hemingway. He was certainly the most recognizable poet on the planet until his death in 1997. His bushy black beard and shining bald head were frequently seen at protests, on posters, in newspapers, and on television, as he told anyone who would listen his views on poetry and politics. Alongside Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel, “On the Road,” “Howl” helped launch the Beat Generation into the public consciousness. It was the first major post-WWII cultural movement in the United States and it later spawned the hippies of the 1960s, and influenced everyone from Bob Dylan to John Lennon. Later, Ginsberg and his Beat friends remained an influence on the punk and grunge movements, along with most other musical genres. -

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge

National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge Nation’s Motto of Pakistan The scroll supporting the shield contains Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s motto in Urdu, which reads as “Iman, Ittehad, Nazm” translated as “Faith, Unity, Discipline” and are intended as the guiding principles for Pakistan. Official Map of Pakistan Official Map of Pakistan is that which was prepared by Mahmood Alam Suhrawardy National Symbol of Pakistan Star and crescent is a National symbol. The star and crescent symbol was the emblem of the Ottoman Empire in the 19th century, and gradually became associated with Islam in late 19th-century Orientalism. National Epic of Pakistan The Hamza Nama or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza narrates the legendary exploits of Amir Hamza, an uncle of the Prophet Muhammad, though most of the stories are extremely fanciful, “a continuous series of romantic interludes, threatening events, narrow escapes, and violent acts National Calendar of Pakistan Fasli which means (harvest) is derived from the Arabic term for division, which in India was applied to the groupings of the seasons. Fasli Calendar is a chronological system introduced by the Mughal emperor Akbar basically for land revenue and records purposes in northern India. Fasli year means period of 12 months from July to Downloaded from www.csstimes.pk | 1 National Symbols of Pakistan | Pakistan General Knowledge June. National Reptile of Pakistan The mugger crocodile also called the Indian, Indus, Persian, Sindhu, marsh crocodile or simply mugger, is found throughout the Indian subcontinent and the surrounding countries, like Pakistan where the Indus crocodile is the national reptile of Pakistan National Mammal of Pakistan The Indus river dolphin is a subspecies of freshwater river dolphin found in the Indus river (and its Beas and Sutlej tributaries) of India and Pakistan. -

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies At

Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Poet Who Nurtured the Beats, Dies at 101 An unapologetic proponent of “poetry as insurgent art,” he was also a publisher and the owner of the celebrated San Francisco bookstore City Lights. By Jesse McKinley Feb. 23, 2021 Lawrence Ferlinghetti, a poet, publisher and political iconoclast who inspired and nurtured generations of San Francisco artists and writers from City Lights, his famed bookstore, died on Monday at his home in San Francisco. He was 101. The cause was interstitial lung disease, his daughter, Julie Sasser, said. The spiritual godfather of the Beat movement, Mr. Ferlinghetti made his home base in the modest independent book haven now formally known as City Lights Booksellers & Publishers. A self-described “literary meeting place” founded in 1953 and located on the border of the city’s sometimes swank, sometimes seedy North Beach neighborhood, City Lights, on Columbus Avenue, soon became as much a part of the San Francisco scene as the Golden Gate Bridge or Fisherman’s Wharf. (The city’s board of supervisors designated it a historic landmark in 2001.) While older and not a practitioner of their freewheeling personal style, Mr. Ferlinghetti befriended, published and championed many of the major Beat poets, among them Allen Ginsberg, Gregory Corso and Michael McClure, who died in May. His connection to their work was exemplified — and cemented — in 1956 with his publication of Ginsberg’s most famous poem, the ribald and revolutionary “Howl,” an act that led to Mr. Ferlinghetti’s arrest on charges of “willfully and lewdly” printing “indecent writings.” In a significant First Amendment decision, he was acquitted, and “Howl” became one of the 20th century’s best-known poems. -

Walt Whitman (1819-1892)

Whitman 1 Walt Whitman (1819-1892) 2 Section headings and information Poems 6 “In Cabin’d Ships at Sea” 7 “We Two, How Long We Were Foole’d” 8 “These I Singing in Spring” 9 “France, the 18th Year of These States” 10 “Year of Meteors (1859-1860)” 11 “Song for All Seas, All Ships” 12 “Gods” 13 “Beat! Beat! Drums!” 14 “Vigil Strange I Kept on the Field one Night” 15 “A March in the Ranks Hard-Prest, and the Road Unknown” 16 “O Captain! My Captain!” 17 “Unnamed Lands” 18 “Warble for Lilac-Time” 19 “Vocalism” 20 “Miracles” 21 “An Old Man’s Thought of School” 22 “Thou Orb Aloft Full-Dazzling” 23 “To a Locomotive in Winter” 24 “O Magnet-South” 25 “Years of the Modern” Source: Leaves of Grass. Sculley Bradley and Harold W. Blodgett, ed. NY: W.W. Norton & Company, 1973. Print. Note: For the IOC, copies of the poems will contain no information other than the title, the poem’s text, and line numbers. Whitman 2 Leaves of Grass, 1881, section headings for those poems within this packet WW: Walt Whitman LG: Leaves of Grass MS: manuscript “Inscriptions” First became a group title for the opening nine poems of LG 1871. In LG 1881 the group was increased to the present twenty-four poems, of which one was new. “Children of Adam” In two of his notes toward poems WW set forth his ideas for this group. One reads: “A strong of Poems (short, etc.), embodying the amative love of woman—the same as Live Oak Leaves do the passion of friendship for man.” (MS unlocated, N and F, 169, No. -

The 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation

Portland State University PDXScholar Young Historians Conference Young Historians Conference 2015 Apr 28th, 1:00 PM - 2:15 PM A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation Jamie L. Rehlaender Lakeridge High School Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians Part of the Cultural History Commons, Legal Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Rehlaender, Jamie L., "A Howl of Free Expression: the 1957 Howl Obscenity Trial and Sexual Liberation" (2015). Young Historians Conference. 1. https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/younghistorians/2015/oralpres/1 This Event is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Young Historians Conference by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Jamie L. Rehlaender Dr. Karen Hoppes HST 201: History of the US Portland State University March 19, 2015 2 A HOWL OF FREE EXPRESSION: THE 1957 HOWL OBSCENITY TRIAL AND SEXUAL LIBERATION Allen Ginsberg’s first recitation of his poem Howl , on October 13, 1955, at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, ended in tears, both from himself and from members of the audience. “The people gasped and laughed and swayed,” One Six Gallery gatherer explained, “they were psychologically had, it was an orgiastic occasion.”1 Ironically, Ginsberg, upon initially writing Howl , had not intended for it to be a publicly shared piece, due in part to its sexual explicitness and personal references. -

The Impact of Allen Ginsberg's Howl on American Counterculture

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Croatian Digital Thesis Repository UNIVERSITY OF RIJEKA FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH Vlatka Makovec The Impact of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl on American Counterculture Representatives: Bob Dylan and Patti Smith Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the M.A.in English Language and Literature and Italian language and literature at the University of Rijeka Supervisor: Sintija Čuljat, PhD Co-supervisor: Carlo Martinez, PhD Rijeka, July 2017 ABSTRACT This thesis sets out to explore the influence exerted by Allen Ginsberg’s poem Howl on the poetics of Bob Dylan and Patti Smith. In particular, it will elaborate how some elements of Howl, be it the form or the theme, can be found in lyrics of Bob Dylan’s and Patti Smith’s songs. Along with Jack Kerouac’s On the Road and William Seward Burroughs’ Naked Lunch, Ginsberg’s poem is considered as one of the seminal texts of the Beat generation. Their works exemplify the same traits, such as the rejection of the standard narrative values and materialism, explicit descriptions of the human condition, the pursuit of happiness and peace through the use of drugs, sexual liberation and the study of Eastern religions. All the aforementioned works were clearly ahead of their time which got them labeled as inappropriate. Moreover, after their publications, Naked Lunch and Howl had to stand trials because they were deemed obscene. Like most of the works written by the beat writers, with its descriptions Howl was pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression and paved the path to its successors who continued to explore the themes elaborated in Howl. -

Using Poetry to Teach Children About the Civil Rights Movement Elouise

Using Poetry to Teach Children About the Civil Rights Movement Elouise Payton Objectives After teaching this unit, I hope that my students will be able to identify with their own history and value their own background and identities. I plan to provide my students with opportunities to reflect upon what they are learning and give them the opportunity to express their feelings in positive ways. I want to support them as they interact and think more critically about their own identities, cultural experiences and the world that they live in. Likewise, in this unit my students will learn about the active roles that African American children and others played in reforming their communities during the era. Furthermore, it is my hope that my students will view themselves as agents of change; understand that they too are active participants in history and that they can play key roles in shaping their own lives and communities. I want my students to read interesting texts related to the Civil Rights Era and be able to discuss, question, think, and infer what is happening in them. This can be accomplished as students respond to texts by asking questions, paraphrasing important information, creating visual images, making comparisons, analyzing and summarizing what they have learned. My students will be encouraged to read more literature written by and about African Americans to support their understanding of the events that happened during the era. I will have students interview relatives and have conversations with their relatives about what they have learned about the history of the Civil Rights Movement. -

Calamus, Drum-Taps, and Whitman's Model of Comradeship

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1996 Calamus, Drum-Taps, and Whitman's Model of Comradeship Charles B. Green College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Green, Charles B., "Calamus, Drum-Taps, and Whitman's Model of Comradeship" (1996). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626051. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-61z8-wk77 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "CALAMUS," DRUM-TAPS, AND WHITMAN’S MODEL OF COMRADESHIP A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of English The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Charles B. Green 1996 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Author Approved, December 1996 Kenneth M. Price Robert SdnoLhick Li chard Lowry 11 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The writer wishes to express his appreciation to Professor Kenneth M. Price, under whose supervision this project was conducted, for his patient guidance and criticism throughout the process. ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to explore the relationship between Whitman's "Calamus" and Drum-Taps poems, and to determine the methods by which the poet communicates what Michael Moon calls in his Disseminating Whitman: Revision and Corporeality in Leaves of Grass "a program" of revising the "meaning of bodily experience" in terms of man to man affection. -

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

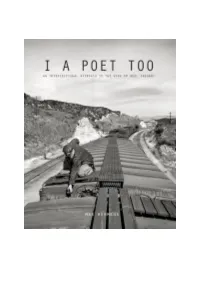

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis.