Culture and Humor in Postwar American Poetry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0056/celebrating-the-best-american-poetry-2018-at-villanova-3-450056.webp)

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova[3]

Celebrating the Best American Poetry 2018 at Villanova February 6, 2019 5:00 Connelly Center Cinema 6:15 (St. David’s Room) Reception and Book Signing Villanova University is honored to host the regional launch of the thirtieth anniversary edition of The Best American Poetry, guest edited by Dana Gioia, David Lehman, general editor. For three decades, the Best American Poetry has served as an annual occasion to recognize new work by American authors; inclusion is one of the great honors established and emerging poets may receive. The anthology was officially launched at New York University, in September 2018, but Villanova now brings together six of the anthology’s authors, along with David Lehman, for an evening of reading, discussion, and fellowship on our campus. David Lehman will chair the event, which will feature short readings from six poets: Maryann Corbett, Ernest Hilbert, Mary Jo Salter, Adrienne Su, Ryan Wilson, and Villanova’s own James Matthew Wilson. The public is warmly invited to this special evening to celebrate the achievement of contemporary letters and to join us for food and conversation afterwards. This event is sponsored by the Honors Program, the Villanova Center for Liberal Education, the Department of English, and the Department of Humanities. For more information, contact James Matthew Wilson, at [email protected] About the poets Maryann Corbett was born in Washington, DC, and grew up in northern Virginia. She earned a BA from the College of William and Mary and an MA and PhD from the University of Minnesota. She has published three books of poetry: Breath Control (2012); Credo for the Checkout Line in Winter (2013), which was a finalist for the Able Muse Book Prize; and Mid Evil (2014), the winner of the Richard Wilbur Award. -

Using Poetry to Teach Children About the Civil Rights Movement Elouise

Using Poetry to Teach Children About the Civil Rights Movement Elouise Payton Objectives After teaching this unit, I hope that my students will be able to identify with their own history and value their own background and identities. I plan to provide my students with opportunities to reflect upon what they are learning and give them the opportunity to express their feelings in positive ways. I want to support them as they interact and think more critically about their own identities, cultural experiences and the world that they live in. Likewise, in this unit my students will learn about the active roles that African American children and others played in reforming their communities during the era. Furthermore, it is my hope that my students will view themselves as agents of change; understand that they too are active participants in history and that they can play key roles in shaping their own lives and communities. I want my students to read interesting texts related to the Civil Rights Era and be able to discuss, question, think, and infer what is happening in them. This can be accomplished as students respond to texts by asking questions, paraphrasing important information, creating visual images, making comparisons, analyzing and summarizing what they have learned. My students will be encouraged to read more literature written by and about African Americans to support their understanding of the events that happened during the era. I will have students interview relatives and have conversations with their relatives about what they have learned about the history of the Civil Rights Movement. -

William Carlos Williams's the Great American Novel

William Carlos Williams’s The Great American Novel: Flamboyance and the Beginning of Art April Boone William Carlos Williams Review, Volume 26, Number 1, Spring 2006, pp. 1-25 (Article) Published by Penn State University Press DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/wcw.2007.0000 For additional information about this article https://muse.jhu.edu/article/216543 [ This content has been declared free to read by the pubisher during the COVID-19 pandemic. ] William Carlos Williams’s The Great American Novel: Flamboyance and the Beginning of Art April Boone U N I V E R S I T Y O F T E N N E S S E E N the early 1920s in Rutherford, New Jersey, William Carlos Williams had serious doubts that the “Great American Novel,” as it Iwas then conceptualized, could ever be written. Though generally known for his revolutionary work in poetry, Williams was also quite an experi- mentalist in prose, claiming in Spring and All that prose and verse “are phases of the same thing” (144). Williams showed concern for the future of American litera- ture in general, including that of the novel. In response to what he viewed as spe- cific problems facing the American novel, problems with American language, and problems inherent in the nature of language itself, Williams created The Great American Novel in 1923. Williams was troubled by the derivative nature of American novels of the time, their lack of originality, and their dependence upon European models; the exhausted material and cliché- ridden language of the his- torical novels of his day; the tendency of such novels to oversimplify or misrepre- sent the American experience; and the formulaic quality of genres such as detec- tive novels. -

Whitman's Civil

Whitman’s Civil War: Writing and Imaging Loss, Death, and Disaster CLASS ONE • Video Transcript >>I am Christopher Merrill, the Director of the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa. And I'm Ed Folsom, Professor of English at the University of Iowa. And it's our pleasure to welcome you to the first session of our Massive Open Online Course, "Whitman's Civil War: Writing and Imaging Loss, Death, and Disaster." Ed and I began composing introductions and commentaries about Whitman's Civil War writings and poetry and prose last summer. And it's interesting to think about this at a moment in our history: we began our writing journey for this MOOC a hundred and fifty years after the end of the Civil War. At a moment in American history where, because of the deaths in Ferguson, Missouri, and in Baltimore, Maryland, as well as rippling around the world - wars in Iraq, in Syria, in Libya, and Yemen, and on and on, we are thinking that, Whitman's attempts to write and image loss and death and disaster have broad applicability. That, what he's trying to do with this great disaster in American history is something that writers face again and again in the 20th century, the bloodiest century of all, and now in our own century, where the forces of chaos seem often to be overwhelming. How did Whitman do that? Yes, and with Whitman, we really have the sense that we are at the beginning of the era that defines us - that still defines our era - this is the first great mechanized war of mass death. -

The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson's Poetry

International Academy Journal Web of Scholar ISSN 2518-167X PHILOLOGY THE MOTIVE OF ASCETICISM IN EMILY DICKENSON’S POETRY Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid, Ph.D. Odlar Yurdu University, Baku, Azerbaijan DOI: https://doi.org/10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Received: 25 November 2019 This paper is an attempt to analyze the poetry of Miss Emily Dickinson Accepted: 12 January 2020 (1830-1886) contributed both American and World literature in order to Published: 31 January 2020 reveal the extent of asceticism in it. Asceticism involves a deep, almost obsessive, concern with such problems as death, the life after death, the KEYWORDS existence of the soul, immortality, the existence of God and heaven, the meaningless of life and etc. Her enthusiastic expressions of life in poems spiritual asceticism, psychological had influenced the development of poetry and became the source of portrait, transcendentalism, Emily inspiration for other poets and poetesses not only in last century but also . Dickenson’s poetry in modern times. The paper clarifies the motives of spiritual asceticism, self-identity in Emily Dickenson’s poetry. Citation: Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. (2020) The Motive of Asceticism in Emily Dickenson’s Poetry. International Academy Journal Web of Scholar. 1(43). doi: 10.31435/rsglobal_wos/31012020/6880 Copyright: © 2020 Abdurahmanova Saadat Khalid. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS The most advanced technology has been used to photo graph and reproduce this manuscript from the microfilm master. UMI films the original text directly from the copy submitted. Thus, some dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from a computer printer. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyrighted material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are re produced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each oversize page is available as one exposure on a standard 35 mm slide or as a 17" x 23" black and white photographic print for an additional charge. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. 35 mm slides or 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Accessing■i the World's UMI Information since 1938 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA Order Number 882462 James Wright’s poetry of intimacy Terman, Philip S., Ph.D. The Ohio State University, 1988 Copyright ©1988 by Terman, Philip S. All rights reserved. UMI 300 N. Zeeb Rd. Ann Arbor, M I 48106 JAMES WRIGHT'S POETRY OF INTIMACY DISSERTATION Presented In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Philip S. -

Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman's Collaborations with the New York School Poets

Timothy Keane Studies in Visual Arts and Communication: an international journal Vol 1, No 2 (2014) on-line ISSN 2393 - 1221 No Real Assurances: Late Modernist Poetics and George Schneeman’s Collaborations with the New York School Poets Timothy Keane City University of New York Abstract: Painter George Schneeman’s collaborations with the New York School poets represent an under-examined, vast body of visual-textual hybrids that resolve challenges to mid-and-late century American art through an indirect alliance with late modernist literary practices. Schneeman worked with New York poets intermittently from 1966 into the early 2000s. This article examines these collagist works from a formalist perspective, uncovering how they incorporate gestural techniques of abstract art and the poetic use of juxtaposition, vortices, analogies, and pictorial and lexical imagism to generate non-representational, enigmatic assemblages. I argue that these late modernist works represent an authentically experimental form, violating boundaries between art and writing, disrupting the venerated concept of single authorship, and resisting the demands of the marketplace by affirming for their creators a unity between art-making and daily life—ambitions that have underpinned every twentieth century avant-garde movement. On first seeing George Schneeman’s painting in the 1960s, poet Alice Notley asked herself, “Is this [art] new? Or old fashioned?”1 Notley was probably reacting to Schneeman’s unassuming, intimate representations of Tuscan landscape and what she called their “privacy of relationship.” The potential newness Notley detected in Schneeman’s “old-fashioned” art might be explained by how his small-scale and quiet paintings share none of the self-conscious flamboyance in much American painting of the 1960s and 1970s. -

Reading by David Lehman

FOR IMMEDIATE PRESS RELEASE 4-5-17 EVENTS: Poets of National Stature Reading Series presents: Leading poet David Lehman o Reading by David Lehman, author of Poems in the Manner Of… at Writer’s Block o Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook, lecture & discussion led by David Lehman. WHO: David Lehman is one of America’s leading poets using humor and everyday language to bring us great insight into the most powerful thoughts and feelings of life. He wrote an article recently regarding Bob Dylan and the Nobel Prize for the Wall Street Journal and was quoted prominently on the topic in the Washington Post. David Lehman’s books include Yeshiva Boys, A Fine Romance: Jewish Songwriters American Songs, and most recently, Poems in the Manner of.... He edits the Best American Poetry series the Oxford Book ofAmerican Poetry. As series editor, he has earned high acclaim for his pivotal role in garnering contemporary American poetry a larger audience. One of the foremost editors, literary critics, and anthologists of contemporary American literature, David Lehman is also one of our most accomplished poets. WHEN: Reading by David Lehman: Saturday, May 20, 7:00-8:30 p.m., Writer’s Block 1020 Fremont St #100, Las Vegas, NV 89101. Dylan, the Nobel, & the Jewish American Songbook – Lecture & Discussion by David Lehman: Sunday, May 21, 3 - 4:30 p.m. Congregation Ner Tamid, Beit Tefillah (Room) 55 N Valle Verde Dr, Henderson, NV 89074. COST: Both events are free and open to the public. CONTACT: Bruce Isaacson, CC Poet Laureate 702-205-7100 or [email protected] Angela M. -

Reflections on Poetry & Social Class

The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. Opening the Field The New American Poetry By the time that Melvin B. Tolson was composing Libretto for the Republic of Liberia, a group of younger poets had already dis- missed the formalism of Eliot and his New Critic followers as old hat. Their “new” position was much closer to that of Langston Hughes and others whom Tolson perceived as out- moded, that is, having yet to learn—or advance—the lessons of Eliotic modernism. Inspired by action painting and bebop, these younger poets valued spontaneity, movement, and authentic expression. Though New Critics ruled the established maga- zines and publishing houses, this new audience was looking for something different, something having as much to do with free- dom as form, and ‹nding it in obscure magazines and readings in bars and coffeehouses. In 1960, many of these poets were pub- lished by a commercial press for the ‹rst time when their poems were gathered in The New American Poetry, 1946–1960. Editor Donald Allen claimed for its contributors “one common charac- teristic: total rejection of all those qualities typical of academic verse.” The extravagance of that “total” characterizes the hyperbolic gestures of that dawn of the atomic age. But what precisely were these poets rejecting? Referring to Elgar’s “Enigma” Variations, 85 The Stamp of Class: Reflections on Poetry and Social Class Gary Lenhart http://www.press.umich.edu/titleDetailLookInside.do?id=104886 The University of Michigan Press, 2005. -

Sensing Sounding: Close Listening to Experimental Asian American Poetry

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2016 Sensing Sounding: Close Listening To Experimental Asian American Poetry Ashley Chang University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Aesthetics Commons, Asian American Studies Commons, and the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Chang, Ashley, "Sensing Sounding: Close Listening To Experimental Asian American Poetry" (2016). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2210. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2210 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2210 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sensing Sounding: Close Listening To Experimental Asian American Poetry Abstract This dissertation examines a selection of Asian American experimental poetries from the 1960’s to the present day through the sensory paradigms of avant-garde aesthetic discourse. By approaching both the poem and racial formation in sonic terms, this dissertation project argues that rethinking the sensory as well as the political ramifications of sounding can help us ecuperr ate Asian American poets’ often overlooked experimentation with poetic form. Specifically, I read the works of Marilyn Chin, Theresa Cha, John Yau, Cathy Park Hong, Mei-mei Berssenbrugge, and Tan Lin. By tracing the historical conditions of Orientalist objectification and e-interrr ogating postmodern theories of -

The Best American Poetry 2009 Series Editor David Lehman 1St Edition Download Free

THE BEST AMERICAN POETRY 2009 SERIES EDITOR DAVID LEHMAN 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE David Wagoner | 9780743299770 | | | | | The Best American Poetry 2009 : Series Editor David Lehman Views Read Edit View history. The list doesn't have to make any sense at all. All right, I'll say weird stuff about the fifty states, just meaningless stuff, and string it all togetherthinks Bibbins's clogged brain one fall morning at the New School. Please enter a valid email address. The editor groups poems of particular styles together, and they seemed to progress from more traditional to those that have a more modern flavor. Email address. Known for his marvelous narrative skill and humane wit, David Wagoner is one of the few poets of his generation to win the universal admiration of his peers. Like, what are the things I would do if I met Moses in a laundry room in a twenty-fifth century spaceship? He has been a contributing editor at The American Scholar[35] sincewhere he acts as quiz master for the weekly column Next Line, Pleasea public poetry-writing contest, in addition to writing various articles. A smile of complicity. For years, the Best American Poetry series, edited by David Lehman, has been on a downward slope using slope in the most generous sense of the word. Lehman, David December 4, And poets in America today are defining nothing as much as they are defining poetry itself. About This Item. Join HuffPost. See our disclaimer. This is gibberish pretending to be poetry. To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. -

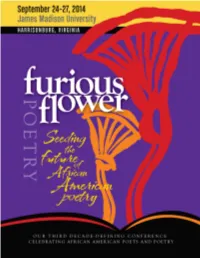

Furiousflower2014 Program.Pdf

Dedication “We are each other’s harvest; we are each other’s business; we are each other’s magnitude and bond.” • GWENDOLYN BROOKS Dedicated to the memory of these poets whose spirit lives on: Ai Margaret Walker Alexander Maya Angelou Alvin Aubert Amiri Baraka Gwendolyn Brooks Lucille Clifton Wanda Coleman Jayne Cortez June Jordan Raymond Patterson Lorenzo Thomas Sherley Anne Williams And to Rita Dove, who has sharpened love in the service of myth. “Fact is, the invention of women under siege has been to sharpen love in the service of myth. If you can’t be free, be a mystery.” • RITA DOVE Program design by RobertMottDesigns.com GALLERY OPENING AND RECEPTION • DUKE HALL Events & Exhibits Special Time collapses as Nigerian artist Wole Lagunju merges images from the Victorian era with Yoruba Gelede to create intriguing paintings, and pop culture becomes bedfellows with archetypal imagery in his kaleidoscopic works. Such genre bending speaks to the notions of identity, gender, power, and difference. It also generates conversations about multicultur- alism, globalization, and transcultural ethos. Meet the artist and view the work during the Furious Flower reception at the Duke Hall Gallery on Wednesday, September 24 at 6 p.m. The exhibit is ongoing throughout the conference, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. FUSION: POETRY VOICED IN CHORAL SONG FORBES CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS Our opening night concert features solos by soprano Aurelia Williams and performances by the choirs of Morgan State University (Eric Conway, director) and James Madison University (Jo-Anne van der Vat-Chromy, director). In it, composer and pianist Randy Klein presents his original music based on the poetry of Margaret Walker, Michael Harper, and Yusef Komunyakaa.