Mislabeled Muses Deborah L

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8021/howl-the-naked-bodies-of-madness-118021.webp)

Howl": the [Naked] Bodies of Madness

promoting access to White Rose research papers Universities of Leeds, Sheffield and York http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/10352/ Published chapter Rodosthenous, George (2005) The dramatic imagery of "Howl": the [naked] bodies of madness. In: Howl for Now. Route Publishing , Pontefract, UK, pp. 53- 72. ISBN 1 901927 25 3 White Rose Research Online [email protected] The dramatic imagery of “Howl”: the [naked] bodies of madness George Rodosthenous …the suffering of America‘s naked mind for love into an eli eli lamma lamma sabacthani saxophone cry that shivered the cities (―Howl‖, 1956) Unlike Arthur Rimbaud who wrote his ―A Season in Hell‖ (1873) when he was only 19 years old, Allen Ginsberg was 29 when he completed his epic poem ―Howl‖ (1956). Both works encapsulate an intense world created by the imagery of words and have inspired and outraged their readers alike. What makes ―Howl‖ relevant to today, 50 years after its first reading, is its honest and personal perspective on life, and its nearly journalistic, but still poetic, approach to depicting a world of madness, deprivation, insanity and jazz. And in that respect, it would be sensible to point out the similarities of Rimbaud‘s concerns with those of Ginsberg‘s. They both managed to create art that changed the status quo of their times and confessed their nightmares in a way that inspired future generations. Yet there is a stark contrast here: for Rimbaud, ―A Season in Hell‖ was his swan song; fortunately, in the case of Ginsberg, he continued to write for decades longer, until his demise in 1997. -

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a Result of Moving to San Francisco in 1954, After His Psychiatric Hospitalizati

Allen Ginsberg, Psychiatric Patient and Poet As a result of moving to San Francisco in 1954, after his psychiatric hospitalization, Allen Ginsberg made a complete transformation from his repressed, fragmented early life to his later life as an openly gay man and public figure in the hippie and environmentalist movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He embodied many contradictory beliefs about himself and his literary abilities. His early life in Paterson, New Jersey, was split between the realization that he was a literary genius (Hadda 237) and the desire to escape his chaotic life as the primary caretaker for his schizophrenic mother (Schumacher 8). This traumatic early life may have lead to the development of borderline personality disorder, which became apparent once he entered Columbia University. Although Ginsberg began writing poetry and protest letters to The New York Times beginning in high school, the turning point in his poetry, from conventional works, such as Dakar Doldrums (1947), to the experimental, such as Howl (1955-1956), came during his eight month long psychiatric hospitalization while a student at Columbia University. Although many critics ignore the importance of this hospitalization, I agree with Janet Hadda, a psychiatrist who examined Ginsberg’s public and private writings, in her assertion that hospitalization was a turning point that allowed Ginsberg to integrate his probable borderline personality disorder with his literary gifts to create a new form of poetry. Ginsberg’s Early Life As a child, Ginsberg expressed a strong desire for a conventional, boring life, where nothing exciting or remarkable ever happened. He frequently escaped the chaos of 2 his mother’s paranoid schizophrenia (Schumacher 11) through compulsive trips to the movies (Hadda 238-39) and through the creation of a puppet show called “A Quiet Evening with the Jones Family” (239). -

The Spirit of the People Will Be Stronger Than the Pigs’ Technology”

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE November 2017 “THE SPIRIT OF THE PEOPLE WILL BE STRONGER THAN THE PIGS’ TECHNOLOGY” An exhibition, a symposium, and a month-long series of events re-examining the interdependent legacies of revolutionary poetry and the militant left in the United States, with a spotlight on Allen Van Newkirk’s Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets (Detroit, Mich. & New York City: 1967-1968) and the recent & upcoming 50th anniversaries of the founding of the Black Panther Party in Oakland, Calif. (1966) and the White Panther Party in Detroit, Mich. (1968) including a presentation of rare ephemera from both groups. Exhibition: 9 November – 29 December 2017 @ Fortnight Institute Symposium: 17 November 2017 @ NYU Page 1 of 6 E XHIBITION A complete run of Guerrilla: Free Newspaper of the Streets serves as the focal point for an exhibition of r evolutionar y le fti s t posters , bro adsides, b oo ks, and ep hemera, ca. 196 4-197 0, a t East Villag e ( Manhattan) a rt gall e ry Fortnight Institute, opening at 6 pm on Thu rsd ay, Novemb er 9 , 2017 a nd c ontinuing through Sun day, December 29. Th e displa y also inc lude s rare, orig inal print m ate rials a nd p osters fro m the Bl ack Pan ther Party, Whi t e Panther Party , Young Lords a nd ot her revolu tion ary g roups. For t he d u ration of the exhib itio n, Fortnig ht Institute will also house a readin g room stock ed with cha pbooks and pa perbacks from leftist mili tant poets o f the era, many of w hose works we re p rinted in G uerrill a, includ ing LeRo i Jones, Diane Di P rima, M arga ret Ran dall, Reg is Deb ray an d o thers. -

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas Collection of Jack Kerouac Material, Circa 1900-2005

KEROUAC, JACK, 1922-1969. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Descriptive Summary Creator: Kerouac, Jack, 1922-1969. Title: John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Extent: 2 linear feet (4 boxes) and 1 oversized papers box (OP) Abstract: Material collected by John Sampas relating to Jack Kerouac and including correspondence, photographs, and manuscripts. Language: Materials entirely in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Use copies have not been made for audiovisual material in this collection. Researchers must contact the Rose Library at least two weeks in advance for access to these items. Collection restrictions, copyright limitations, or technical complications may hinder the Rose Library's ability to provide access to audiovisual material. Terms Governing Use and Reproduction All requests subject to limitations noted in departmental policies on reproduction. Related Materials in Other Repositories Jack Kerouac papers, New York Public Library Related Materials in This Repository Jack Kerouac collection and Jack and Stella Sampas Kerouac papers Source Purchase, 2015 Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study. Copies supplied may not be copied for others or otherwise distributed without prior consent of the holding repository. John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, circa 1900-2005 Manuscript Collection No. 1343 Citation [after identification of item(s)], John Sampas collection of Jack Kerouac material, Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library, Emory University. -

POETS HATING POETRY Can’T Anyone Give Poetry a Break? by Ryan Stuart Lowe

Spring | Summer 2017 OKLAHOMA HUMANITIES Culture | Issues | Ideas dLearning to love like not hate poetry 2017—A Year of New Initiatives At Oklahoma Humanities, the will explore this challenging period in year 2017 begins with continued our nation’s history. Concurrent with the ANN THOMPSON commitment to serving the public magazine and local programming will Executive Director through inspired and inspiring cultural be the September debut of an 18-hour, experiences. In addition to successful NEH-funded Ken Burns documentary programs like Museum on Main Street; on PBS called The Vietnam War. Our Let’s Talk About it, Oklahoma; Oklahoma objective in focusing on the Vietnam era Humanities magazine; and, of course, is to remind those of us who remember our grants program; we’re working on the war to think critically of lessons special initiatives that we’re proud to learned (and not learned) from the war, bring to our state. and to inform younger generations of First, through a partnership with the challenging issues of that period the Ralph Ellison Foundation, we are that continue to impact our national sponsoring a series of public meetings identity—the civil rights movement, on race relations in Oklahoma. Using the the changing roles of women, student texts of one of Oklahoma’s most esteemed writers and favorite sons, the Foundation activism, how we treat veterans, and the will encourage community conversations roles of music, literature, television, and to foster greater understanding and to the media in forming American opinion. promote the common good. This year promises to be meaningful Second is a multi-faceted look at the and rich in opportunities and, as always, Vietnam era. -

Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation

DOCTORAL THESIS Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation Reynolds, Loni Sophia Award date: 2011 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 Irrational Doorways: Religion and Spirituality in the Work of the Beat Generation by Loni Sophia Reynolds BA, MA A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of PhD Department of English and Creative Writing University of Roehampton 2011 Reynolds i ABSTRACT My thesis explores the role of religion and spirituality in the work of the Beat Generation, a mid-twentieth century American literary movement. I focus on four major Beat authors: William S. Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Jack Kerouac, and Gregory Corso. Through a close reading of their work, I identify the major religious and spiritual attitudes that shape their texts. All four authors’ religious and spiritual beliefs form a challenge to the Modern Western worldview of rationality, embracing systems of belief which allow for experiences that cannot be empirically explained. -

Journeys of the Beat Generation

My Witness Is the Empty Sky: Journeys of the Beat Generation Christelle Davis MA Writing (by thesis) 2006 Certificate of Authorship/Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all the information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Candidate 11 Acknowledgements A big thank you to Tony Mitchell for reading everything and coping with my disorganised and rushed state. I'm very appreciative of the Kerouac Conference in Lowell for letting me attend and providing such a unique forum. Thank you to Buster Burk, Gerald Nicosia and the many other Beat scholars who provided some very entertaining e mails and opinions. A big slobbering kiss to all my beautiful friends for letting me crash on couches all over the world and always ringing, e mailing or visiting just when I'm about to explode. Thanks Andre for making me buy that first copy of On the Road. Thank you Tim for the cups of tea and hugs. I'm very grateful to Mum and Dad for trying to make everything as easy as possible. And words or poems are not enough for my brother Simon for those silly months in Italy and turning up at that conference, even if you didn't bother to wear shoes. -

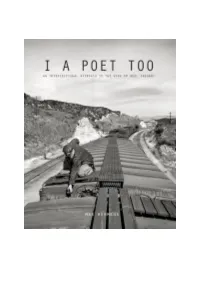

An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady

“I a poet too”: An Intersectional Approach to the Work of Neal Cassady “Look, my boy, see how I write on several confused levels at once, so do I think, so do I live, so what, so let me act out my part at the same time I’m straightening it out.” Max Hermens (4046242) Radboud University Nijmegen 17-11-2016 Supervisor: Dr Mathilde Roza Second Reader: Prof Dr Frank Mehring Table of Contents Acknowledgements 3 Abstract 4 Introduction 5 Chapter I: Thinking Along the Same Lines: Intersectional Theory and the Cassady Figure 10 Marginalization in Beat Writing: An Emblematic Example 10 “My feminism will be intersectional or it will be bullshit”: Towards a Theoretical Framework 13 Intersectionality, Identity, and the “Other” 16 The Critical Reception of the Cassady Figure 21 “No Profane History”: Envisioning Dean Moriarty 23 Critiques of On the Road and the Dean Moriarty Figure 27 Chapter II: Words Are Not For Me: Class, Language, Writing, and the Body 30 How Matter Comes to Matter: Pragmatic Struggles Determine Poetics 30 “Neal Lived, Jack Wrote”: Language and its Discontents 32 Developing the Oral Prose Style 36 Authorship and Class Fluctuations 38 Chapter III: Bodily Poetics: Class, Gender, Capitalism, and the Body 42 A poetics of Speed, Mobility, and Self-Control 42 Consumer Capitalism and Exclusion 45 Gender and Confinement 48 Commodification and Social Exclusion 52 Chapter IV: Writing Home: The Vocabulary of Home, Family, and (Homo)sexuality 55 Conceptions of Home 55 Intimacy and the Lack 57 “By their fruits ye shall know them” 59 1 Conclusion 64 Assemblage versus Intersectionality, Assemblage and Intersectionality 66 Suggestions for Future Research 67 Final Remarks 68 Bibliography 70 2 Acknowledgements First off, I would like to thank Mathilde Roza for her assistance with writing this thesis. -

English Department Newsletter May 2016 Kamala Nehru College

WHITE NOISE English Department Newsletter May 2016 Cover Art by Vidhipssa Mohan Vidhipssa Art by Cover Kamala Nehru College, University of Delhi Contents Editorial Poetry and Short Prose A Little Girl’s Day 4 Aishwarya Gosain The Devil Wears Westwood 4 Debopriyaa Dutta My Dad 5 Suma Sankar Is There Time? 5 Shubhali Chopra Numb 6 Niharika Mathur Why Solve a Crime? 6 Apoorva Mishra Pitiless Time 7 Aisha Wahab Athazagoraphobia 7 Debopriyaa Dutta I Beg Your Pardon 8 Suma Sankar Toska 8 Debopriyaa Dutta Prisoner of Azkaban 8 Abeen Bilal Saudade 9 Debopriyaa Dutta Dusk 11 Sagarika Chakraborty Man and Time 11 Elizabeth Benny Pink Floyd’s Idea of Time 12 Aishwarya Vishwanathan 1 Comics Bookstruck 14 Abeen Bilal The Kahanicles of Maa-G and Bahu-G 15 Pratibha Nigam Rebel Without a Pause 16 Jahnavi Gupta Research Papers Heteronormativity in Homosexual Fanfiction 17 Sandhra Sur Identity and Self-Discovery: Jack Kerouac’s On the Road 20 Debopriyaa Dutta Improvisation and Agency in William Shakespeare’s Twelfth Night 26 Sandhra Sur Woman: Her Own Prisoner or the Social Jailbird and the Question of the Self 30 Shritama Mukherjee Deconstructing Duryodhana – The Villain 37 Takbeer Salati Translations Grief-Stricken (Translation of Pushkar Nath’s Urdu story “Dard Ka Maara”) 39 Maniza Khalid and Abeen Bilal Alone (Translation of Mahasweta Devi’s Bengali story “Ekla”) 42 Eesha Roy Chowdhury Beggar’s Reward (Translation of a Hindi Folktale) 51 Vidhipssa Mohan Translation of a Hindi Oral Folktale 52 Sukriti Pandey Artwork Untitled 53 Anu Priya Untitled 53 Anu Priya Saving Alice 54 Anu Priya 2 Editorial Wait, what is that? Can you hear it? Can you feel it? That nagging at the back of your mind as you lie in bed till ten in the morning when you have to submit an assignment the next day? That bittersweet feeling as you meet a friend after ages knowing that tomorrow you will have to retire to your mundane life. -

Poetics at New College of California

The University of San Francisco USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship Gleeson Library | Geschke Center 2-2020 Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California Patrick James Dunagan University of San Francisco, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation Dunagan, Patrick James, "Assembling evidence of the alternative: Roots and routes: Poetics at New College of California" (2020). Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship. 30. https://repository.usfca.edu/librarian/30 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Gleeson Library | Geschke Center at USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Gleeson Library Faculty and Staff Research and Scholarship by an authorized administrator of USF Scholarship: a digital repository @ Gleeson Library | Geschke Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ASSEMBLING EVIDENCE OF THE ALTERNATIVE: Roots And Routes POETICS AT NEW COLLEGE OF CALIFORNIA Anthology editor Patrick James Dunagan presenting material co-written with fellow anthology editors Marina Lazzara and Nicholas James Whittington. abstract The Poetics program at New College of California (ca. 1980-2000s) was a distinctly alien presence among graduate-level academic programs in North America. Focused solely upon the study of poetry, it offered a truly alternative approach to that found in more traditional academic settings. Throughout the program's history few of its faculty possessed much beyond an M.A. -

Beat Culture and the Grateful Dead

Beat Culture and the Grateful Dead OVERVIEW ESSENTIAL QUESTION How did beat writers like Jack Kerouac influence the Grateful Dead’s music? OVERVIEW Note to teacher: The handout in this lesson contains descriptions of drug use. Our hope is that the language used, which quite often details the repulsive nature of addiction rather than glamorizing it, will paint a realistic, and not desirable picture of drug use. However, we suggest reviewing the handout and making a plan for using it with your classroom before working with the lesson. In post-WWII America, a radical new movement took over the literary world. Anchored by writers like Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burroughs, the Beat Generation, as they came to be known, viewed conventional American culture with disillusionment. They embraced things like free sexuality and drug use, explorations of Eastern religion, and a shirking of materialism in favor of a liberated lifestyle. One of the era’s most definitive works, Jack Kerouac’s 1957 novel On the Road, explores these themes through a semi-autobiographical road trip across America. By the 1960s, the ideals expounded by the Beats were perhaps no better exemplified in musical culture than by the Grateful Dead. For their 30-year career, the Grateful Dead embraced the liberating, always-on-the-move lifestyle promoted by works such as Kerouac’s On the Road. The band eschewed industry conventions by becoming a perpetual “road band,” gaining a reputation not through chart hits, lavish studio recordings, or flashy media appearances, but via ceaseless touring and adventurous, inclusive,and always-changing live performances. -

William Burroughs: Sailor of the Soul. A.J. Lees Reta Lila Weston Institute

William Burroughs: Sailor of the Soul. A.J. Lees Reta Lila Weston Institute of Neurological Sciences, Institute of Neurology, University College London WC1 ([email protected]). Abstract In 1953 William Seward Burroughs made several important and largely unrecognised discoveries relating to the composition and clinical pharmacological effects of the hallucinogenic plant potion known as yagé or ayahuasca. Illustrations of Burroughs’ voucher sample of Psychotria viridis and his letter to the father of modern ethnobotany Richard Evans Schultes are published here for the very first time. Introduction. William Seward Burroughs (1914-1997) demonised by post-War American society eventually came to be regarded by many notable critics as one of the finest writers of the twentieth century. In my article entitled Hanging around with the Molecules and my book Mentored by a Madman; The William Burroughs Experiment I have described how as a young medical student I forged a Mephistolean pact with ‘the hard man of hip’ that allowed me to continue my medical studies. Many years later Burroughs was behind my determination to resurrect apomorphine for the treatment of Parkinson’s disease (Stibe, Lees, and Stern 1987) and employ the Dreamachine to better understand the neurobiology of visual hallucinations. Junkie helped me understand the dopamine dysregulation syndrome, far better than any learned paper. My patients craved, then wanted but never enjoyed their anti-Parkinson Ian medication (Giovannoni et al. 2000) . After reading the Yage Letters in 1978 I also came to see William Burroughs as a shady traveller in the grand tradition of the Victorian naturalists. In this article I reveal how his ethnobotanising in the Colombian and Peruvian Amazon contributed an important and largely unrecognised footnote to the unraveling of the phytochemistry of ayahuasca (yagé).