An Assessment of the Development of Target Marking Techniques to the Prosecution of the Bombing Offensive During the Second World War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fstate Scientist: Omond Mckillop Solandt and Government Science

fState Scientist: Omond McKillop Solandt and Government Science in War and Hostile Peace, 1939-1956/ Scientifique.de l'Etat: Omond McKillop Solandt et la Science du Gouvernement lors de la Guerre et de la Paix Hostile, 1939-1956 A Thesis Submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies of the Royal Military College of Canada by Jason Sean Ridler, MA Royal Military College of Canada, 2001 BA (Hons.) York University, 1999 In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2008 ©This thesis may be used within the Department of National Defence but copyright for open publication remains the property of the author. Library and Bibliotheque et 1*1 Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47901-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-47901-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Plntemet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. -

Doolittle and Eaker Said He Was the Greatest Air Commander of All Time

Doolittle and Eaker said he was the greatest air commander of all time. LeMayBy Walter J. Boyne here has never been anyone like T Gen. Curtis E. LeMay. Within the Air Force, he was extraordinarily successful at every level of com- mand, from squadron to the entire service. He was a brilliant pilot, preeminent navigator, and excel- lent bombardier, as well as a daring combat leader who always flew the toughest missions. A master of tactics and strategy, LeMay not only played key World War II roles in both Europe and the Pacific but also pushed Strategic Air Command to the pinnacle of great- ness and served as the architect of victory in the Cold War. He was the greatest air commander of all time, determined to win as quickly as possible with the minimum number of casualties. At the beginning of World War II, by dint of hard work and train- ing, he was able to mold troops and equipment into successful fighting units when there were inadequate resources with which to work. Under his leadership—and with support produced by his masterful relations with Congress—he gained such enor- During World War II, Gen. Curtis E. LeMay displayed masterful tactics and strategy that helped the US mous resources for Strategic Air prevail first in Europe and then in the Pacific. Even Command that American opponents Soviet officers and officials acknowledged LeMay’s were deterred. brilliant leadership and awarded him a military deco- “Tough” is always the word that ration (among items at right). springs to mind in any consideration of LeMay. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

Lord Healey CH MBE PC

ROYAL AIR FORCE HISTORICAL SOCIETY JOURNAL 31 (Incorporating the Proceedings of the Bomber Command Association’s 60th Anniversary Symposium) 2 The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the contributors concerned and are not necessarily those held by the Royal Air Force Historical Society. Photographs credited to MAP have been reproduced by kind permission of Military Aircraft Photographs. Copies of these, and of many others, may be obtained via http://www.mar.co.uk First published in the UK in 2004 by the Royal Air Force Historical Society All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing. ISSN 1361 4231 Typeset by Creative Associates 115 Magdalen Road Oxford OX4 1RS Printed by Advance Book Printing Unit 9 Northmoor Park Church Road Northmoor OX29 5UH 3 CONTENTS RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR 4 DEFENCE – The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC HOW DECISIVE WAS THE ROLE OF ALLIED AIR POWER 17 IN THE WAR IN THE PACIFIC, 1941-1945? by Sqn Ldr S I Richards SUMMARY OF THE MINUTES OF THE SEVENTEENTH 47 ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING HELD IN THE ROYAL AIR FORCE CLUB ON 10 JUNE 2003 FEEDBACK 51 DEREK WOOD – AN OBITUARY 55 BOOK REVIEWS 56 PROCEEDINGS OF THE BOMBER COMMAND 82 ASSOCIATION 60TH ANNIVERSARY SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE RAF MUSEUM, HENDON ON 12 OCTOBER 2002 UNDER THE CHAIRMANSHIP OF AIR MSHL SIR JOHN CURTISS KCB KBE 4 RECOLLECTIONS OF A SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENCE The Rt Hon The Lord Healey CH MBE PC I should perhaps start by saying that there is no specific theme to what I have to say. -

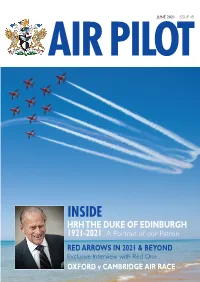

June 2021 Issue 45 Ai Rpi Lo T

JUNE 2021 ISSUE 45 AI RPI LO T INSIDE HRHTHE DUKE OF EDINBURGH 1921-2021 A Portrait of our Patron RED ARROWS IN 2021 & BEYOND Exclusive Interview with Red One OXFORD v CAMBRIDGE AIR RACE DIARY With the gradual relaxing of lockdown restrictions the Company is hopeful that the followingevents will be able to take place ‘in person’ as opposed to ‘virtually’. These are obviously subject to any subsequent change THE HONOURABLE COMPANY in regulations and members are advised to check OF AIR PILOTS before making travel plans. incorporating Air Navigators JUNE 2021 FORMER PATRON: 26 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Duxford His Royal Highness 30 th T&A Committee Air Pilot House (APH) The Prince Philip Duke of Edinburgh KG KT JULY 2021 7th ACEC APH GRAND MASTER: 11 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Henstridge His Royal Highness th The Prince Andrew 13 APBF APH th Duke of York KG GCVO 13 Summer Supper Girdlers’ Hall 15 th GP&F APH th MASTER: 15 Court Cutlers’ Hall Sqn Ldr Nick Goodwyn MA Dip Psych CFS RAF (ret) 21 st APT/AST APH 22 nd Livery Dinner Carpenters’ Hall CLERK: 25 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Weybourne Paul J Tacon BA FCIS AUGUST 2021 Incorporated by Royal Charter. 3rd Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Lee on the Solent A Livery Company of the City of London. 10 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Popham PUBLISHED BY: 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club The Honourable Company of Air Pilots, Summer BBQ White Waltham Air Pilots House, 52A Borough High Street, London SE1 1XN SEPTEMBER 2021 EMAIL : [email protected] 15 th APPL APH www.airpilots.org 15 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Oaksey Park th EDITOR: 16 GP&F APH Allan Winn EMAIL: [email protected] 16 th Court Cutlers’ Hall 21 st Luncheon Club RAF Club DEPUTY EDITOR: 21 st Tymms Lecture RAF Club Stephen Bridgewater EMAIL: [email protected] 30 th Air Pilot Flying Club Fly-in Compton Abbas SUB EDITOR: Charlotte Bailey Applications forVisits and Events EDITORIAL CONTRIBUTIONS: The copy deadline for the August 2021 edition of Air Pilot Please kindly note that we are ceasing publication of is 1 st July 2021. -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

For 30 Minutes, James H. Howard Single-Handedly Fought Off Marauding German Fighters to Defend the B-17S of 401St Bomb Group. for That, He Received the Medal of Honor

For 30 minutes, James H. Howard single-handedly fought off marauding German fighters to defend the B-17s of 401st Bomb Group. For that, he received the Medal of Honor. One-Man Air Force By Rebecca Grant Mustang pilot who took on the German Air Force single-handedly, and saved on Nazi aircraft and fuel production. our 401st Bomb Group from disaster?” uesday, Jan. 11, 1944, was Devastating missions to targets such wondered Col. Harold Bowman, the a rough day for the B-17Gs as Ploesti in Romania had already unit’s commander. of the 401st Bomb Group. produced Medal of Honor recipients. Soon the bomber pilots knew—and TIt was their 14th mission, but the Many were awarded posthumously, and so did those back home. first one on which they took heavy nearly all went to bomber crewmen. “Maj. James H. Howard was identi- losses—four aircraft missing in ac- Waist gunners, pilots, and naviga- fied today as the lone United States tion after bombing Me 110 fighter tors—all were carrying out heroic acts fighter pilot who for more than 30 production plants at Oschersleben and in the face of the enemy. minutes fought off about 30 Ger- Halberstadt, Germany. The lone P-51 pilot on this bomb- man fighters trying to attack Eighth Turning for home, they witnessed ing run would, in fact, become the Air Force B-17 formations returning an amazing sight: A single P-51 stayed only fighter pilot awarded the Medal from Oschersleben and Halberstadt with them for an incredible 30 minutes of Honor in World War II’s European in Germany,” reported the New York on egress, chasing off German fighters Theater. -

A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians

RAF COLLEGE CRANWELL “The Cranwellian Many” A Tribute to Bomber Command Cranwellians Version 1.0 dated 9 November 2020 IBM Steward 6GE In its electronic form, this document contains underlined, hypertext links to additional material, including alternative source data and archived video/audio clips. [To open these links in a separate browser tab and thus not lose your place in this e-document, press control+click (Windows) or command+click (Apple Mac) on the underlined word or image] Bomber Command - the Cranwellian Contribution RAF Bomber Command was formed in 1936 when the RAF was restructured into four Commands, the other three being Fighter, Coastal and Training Commands. At that time, it was a commonly held view that the “bomber will always get through” and without the assistance of radar, yet to be developed, fighters would have insufficient time to assemble a counter attack against bomber raids. In certain quarters, it was postulated that strategic bombing could determine the outcome of a war. The reality was to prove different as reflected by Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris - interviewed here by Air Vice-Marshal Professor Tony Mason - at a tremendous cost to Bomber Command aircrew. Bomber Command suffered nearly 57,000 losses during World War II. Of those, our research suggests that 490 Cranwellians (75 flight cadets and 415 SFTS aircrew) were killed in action on Bomber Command ops; their squadron badges are depicted on the last page of this tribute. The totals are based on a thorough analysis of a Roll of Honour issued in the RAF College Journal of 2006, archived flight cadet and SFTS trainee records, the definitive International Bomber Command Centre (IBCC) database and inputs from IBCC historian Dr Robert Owen in “Our Story, Your History”, and the data contained in WR Chorley’s “Bomber Command Losses of the Second World War, Volume 9”. -

Exeter Blitz for Adobe

Devon Libraries Exeter Blitz Factsheet 17 On the night of 3 rd - 4 th of May 1942, Exeter suffered its most destructive air raid of the Second World War. 160 high explosive bombs and 10,000 incendiary devices were dropped on the city. The damage inflicted changed the face of the city centre forever. Exeter suffered nineteen air raids between August 1940 and May 1942. The first was on the night of 7 th – 8 th of August 1940, when a single German bomber dropped five high explosive bombs on St. Thomas. Luckily no one was hurt and the damage was slight. The first fatalities were believed to have been in a raid on 17 th September 1940, when a house in Blackboy Road was destroyed, killing four boys. In most of the early raids it is likely that the city was not the intended target. The Luftwaffe flew over Exeter on its way towards the industrial cities to the north. It is possible that these earlier attacks on Exeter were caused by German bombers jettisoning unused bombs on the city when returning from raiding these industrial targets. It was not until the raids of 1942 that Exeter was to become the intended target. The town of Lubeck is a port on the Baltic; it had fine medieval architecture reflecting its wealth and importance. Although it was used to supply the German army and had munitions factories on the outskirts of the town, it was strategically unimportant. The bombing of this town on the night of 28 th – 29 th March on the orders of Bomber Command is said to be the reason why revenge attacks were carried out on ‘some of the most beautiful towns in England’. -

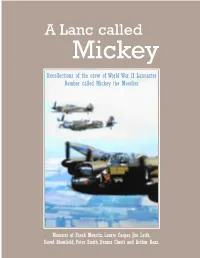

A Lanc Called Mickey

A Lanc called Mickey Recollections of the crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Memoirs of Frank Mouritz, Laurie Cooper, Jim Leith, David Blomfield, Peter Smith, Dennis Cluett and Arthur Bass. Recollections of a crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Contents Introduction .............................................................................. 2 Abbreviations Used ................................................................... 3 Mickey the Moocher .................................................................. 5 Frank Mouritz ............................................................................ 7 No 5 Initial Training School, Clontarf .......................................................... 7 No 9 Elementary Flying Training School, Cunderdin .................................... 10 No 4 Service Flying Training School, Geraldton .......................................... 11 No 5 Embarkation Depot ......................................................................... 12 No 1 Embarkation Depot, Ascot Vale ......................................................... 13 At Sea .................................................................................................. 14 Across America ...................................................................................... 16 Crossing the Atlantic .............................................................................. 17 United Kingdom, First Stop Brighton ........................................................ -

First Developments of Electronic Navigation Systems

ARTICLE HOW TELEVISION €˜GHOSTS€™ CONTRIBUTED TO POSITIONING First Developments of Electronic Navigation Systems Before and during the Second World War, there were several developments in electronics that changed the course of hydrographic history. These aircraft bombing systems were what ultimately led from the medium-frequency systems to super-high-frequency navigation systems that characterised navigational control for hydrographic surveying throughout much of the world for the next 50 years. Not by coincidence did they also lead to many advances in distance measurement in geodetic and plane surveying. Oboe, Gee, Decca and Loran were developed by the British for various types of navigation during the war. Oboe was the equivalent of a super-high-frequency range- range system in which a bombing aircraft would follow a pre-set range arc from one station called the ‘cat' and would drop its ordnance when it intersected a second predetermined arc from a second station termed the ‘mouse'. This system was capable of placing bombs within at least 65 metres of the desired target. Gee, Decca and Loran were usually set up so that navigation was accomplished by observing and plotting intersecting hyperbolic lines of position. Accordingly, they had varying accuracies depending on factors such as system frequency, hyperbolic lane expansion, lines-of- position intersection angles and the weather. The US contribution to these navigation methods was a 300MHz line-of-sight system called Shoran (an acronym for short-range navigation). The origins of Shoran can be traced to a serendipitous discovery before the war. Stuart Seeley, an engineer with the Radio Corporation of America, developed a concept for an extremely accurate navigation system based not on work with radar, but with television. -

2007 Lnstim D'hi,Stoire Du Temp

WORLD "TAR 1~WO STlIDIES ASSOCIATION (formerly American Committee on the History ofthe Second World War) Mark P. l'arilIo. Chai""an Jona:han Berhow Dl:pat1menlofHi«ory E1izavcla Zbeganioa 208 Eisenhower Hall Associare Editors KaDsas State University Dct>artment ofHistory Manhattan, Knnsas 66506-1002 208' Eisenhower HnJl 785-532-0374 Kansas Stale Univemty rax 785-532-7004 Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 parlllo@,'<su.edu Archives: Permanent Directors InstitlJle for Military History and 20" Cent'lly Studies a,arie, F. Delzell 22 J Eisenhower F.all Vandcrbijt Fai"ersity NEWSLETTER Kansas State Uoiversit'j Manhattan, Kansas 66506-1002 Donald S. Detwiler ISSN 0885·-5668 Southern Ulinoi' Va,,,,,,,sity The WWT&« is a.fIi!iilI.etf witJr: at Ccrbomlale American Riston:a1 A."-'iociatioG 400 I" Street, SE. T.!rms expiring 100(, Washingtoo, D.C. 20003 http://www.theah2.or9 Call Boyd Old Dominio" Uaiversity Comite internationa: dlli.loire de la Deuxii:me G""",, Mondiale AI"".nde< CochrnIl Nos. 77 & 78 Spring & Fall 2007 lnstiM d'Hi,stoire du Temp. PreSeDt. Carli5te D2I"n!-:'ks, Pa (Centre nat.onal de I. recberche ,sci,,,,tifiqu', [CNRSJ) Roj' K. I'M' Ecole Normale S<rpeneure de Cach411 v"U. Crucis, N.C. 61, avenue du Pr.~j~'>Ut WiJso~ 94235 Cacllan Cedex, ::'C3nce Jolm Lewis Gaddis Yale Universit}' h<mtlJletor MUitary HL'mry and 10'" CenJury Sllldie" lIt Robin HiRbam Contents KaIUa.r Stare Universjly which su!'prt. Kansas Sl.ll1e Uni ....ersity the WWTSA's w-'bs;te ":1 the !nero.. at the following ~ljjrlrcs:;: (URL;: Richa.il E. Kaun www.k··stare.eDu/his.tD.-y/instltu..:..; (luive,.,,)' of North Carolw.