Doolittle and Eaker Said He Was the Greatest Air Commander of All Time

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

0511Bases.Pdf

Guide to Air Force Installations Worldwide ■ 2011 USAF Almanac Active Duty Installations Abbreviations ABW/G Air Base Wing/Group This section includes Air Force owned and operated command: ACC. Major units/missions: 9th ACW/S Air Control Wing/Squadron facilities around the world. (It also lists the former RW (ACC), ISR and UAV operations; 548th ISRG AFB Air Force Base USAF bases now under other service leadership (AFISRA), DCGS; 940th Wing (AFRC), C2, ISR, AFDW Air Force District of Washington as joint bases.) It is not a complete list of units and UAV operations. History: opened October AFGLSC Air Force Global Logistics Support Center by base. Many USAF installations host numerous 1942 as Army’s Camp Beale. Named for Edward F. AFISRA Air Force ISR Agency tenants, not just other USAF units but DOD, joint, Beale, a former Navy officer who became a hero AFNWC Air Force Nuclear Weapons Center AFOSI Air Force Office of Special Investigations other service, and federal and civil entities. of the Mexican-American War and early devel- AFRICOM US Africa Command oper of California, as well as a senior appointee/ AFRL Air Force Research Laboratory Altus AFB, Okla. 73523-5000. Nearest city: Al- diplomat for four Presidents. Transferred to USAF AFS Air Force Station tus. Phone: 580-482-8100. Owning command: 1948. Designated AFB April 1951. AFWA Air Force Weather Agency AETC. Unit/mission: 97th AMW (AETC), training. AGOW Air Ground Operations Wing History: activated January 1943. Inactivated Brooks City-Base, Tex., 78235-5115. Nearest ALC Air Logistics Center May 1945. Reactivated August 1953. city: San Antonio. -

Canadian Airmen Lost in Wwii by Date 1943

CANADA'S AIR WAR 1945 updated 21/04/08 January 1945 424 Sqn. and 433 Sqn. begin to re-equip with Lancaster B.I & B.III aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). 443 Sqn. begins to re-equip with Spitfire XIV and XIVe aircraft (RCAF Sqns.). Helicopter Training School established in England on Sikorsky Hoverfly I helicopters. One of these aircraft is transferred to the RCAF. An additional 16 PLUTO fuel pipelines are laid under the English Channel to points in France (Oxford). Japanese airstrip at Sandakan, Borneo, is put out of action by Allied bombing. Built with forced labour by some 3,600 Indonesian civilians and 2,400 Australian and British PoWs captured at Singapore (of which only some 1,900 were still alive at this time). It is decided to abandon the airfield. Between January and March the prisoners are force marched in groups to a new location 160 miles away, but most cannot complete the journey due to disease and malnutrition, and are killed by their guards. Only 6 Australian servicemen are found alive from this group at the end of the war, having escaped from the column, and only 3 of these survived to testify against their guards. All the remaining enlisted RAF prisoners of 205 Sqn., captured at Singapore and Indonesia, died in these death marches (Jardine, wikipedia). On the Russian front Soviet and Allied air forces (French, Czechoslovakian, Polish, etc, units flying under Soviet command) on their front with Germany total over 16,000 fighters, bombers, dive bombers and ground attack aircraft (Passingham & Klepacki). During January #2 Flying Instructor School, Pearce, Alberta, closes (http://www.bombercrew.com/BCATP.htm). -

The US Army Air Forces in WWII

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES AIR FORCE Air Force Historical Studies Office 28 June 2011 Errata Sheet for the Air Force History and Museum Program publication: With Courage: the United States Army Air Forces in WWII, 1994, by Bernard C. Nalty, John F. Shiner, and George M. Watson. Page 215 Correct: Second Lieutenant Lloyd D. Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 218 Correct Lieutenant Hughes To: Second Lieutenant Lloyd H. Hughes Page 357 Correct Hughes, Lloyd D., 215, 218 To: Hughes, Lloyd H., 215, 218 Foreword In the last decade of the twentieth century, the United States Air Force commemorates two significant benchmarks in its heritage. The first is the occasion for the publication of this book, a tribute to the men and women who served in the U.S. Army Air Forces during World War 11. The four years between 1991 and 1995 mark the fiftieth anniversary cycle of events in which the nation raised and trained an air armada and com- mitted it to operations on a scale unknown to that time. With Courage: U.S.Army Air Forces in World War ZZ retells the story of sacrifice, valor, and achievements in air campaigns against tough, determined adversaries. It describes the development of a uniquely American doctrine for the application of air power against an opponent's key industries and centers of national life, a doctrine whose legacy today is the Global Reach - Global Power strategic planning framework of the modern U.S. Air Force. The narrative integrates aspects of strategic intelligence, logistics, technology, and leadership to offer a full yet concise account of the contributions of American air power to victory in that war. -

HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDING SURVEY Southwest System Support Office National Park Service P.O

KELLY AIR FORCE BASE, CADET BARRACKS HABS No. TX-3396-AG (Kelly Air Force Base, Building 1676) 205 Gilmore Drive San Antonio Bexar County Texas PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL AND DESCRIPTIVE DATA FIELD RECORDS HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDING SURVEY Southwest System Support Office National Park Service P.O. Box 728 Santa Fe, New Mexico 87504 HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY KELLY AIR FORCE BASE, CADET BARRACKS HABS No. TX-3396-AG (Kelly Air Force Base, Building 1676) Location: 205 Gilmore Drive San Antonio Bexar County Texas Quadrangle BT~4 CoordtnateS'~-t4, -Northillg~ 56300rr,~0 (San Antonio, Texas, 7.S-minute USGS Quadrangle) Date of Construction: November 24, 1940 Present Owner: U.S. Air Force Kelly Air Force Base San Antonio, Texas 78241 Current Occupants: 76 SPTG/SUBMO; Visiting Officers Quarters (VOQ) (1-10) Original Owners: U.S. Army; U.S. Army Air Force (Kelly Field) Original Use: Cadet Barracks and Open Mess Current Use: VOQ and Officers' Club KELLY AIR FORCE BASE. CADET BARRACKS (Kelly Air Force Base, Building 1676) HABS No. TX-3396-AG (Page 2) Significance: Building 1676 was completed on November 24, 1940, and was first used as a Cadet Barracks to replace dilapidated World War I facilities. In 1943, when flight training ceased at Kelly Air Force Base (AFB), the building was redesignated as a Bachelor Officers' Quarters and Operations Hotel (OPS). The building was associated with activities of the San Antonio Air Service Command (1944-1946) and San Antonio Air Materiel Area (1946-1974) during a time when Kelly Field and depot were the largest such facilities in the world. -

A Lanc Called Mickey

A Lanc called Mickey Recollections of the crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Memoirs of Frank Mouritz, Laurie Cooper, Jim Leith, David Blomfield, Peter Smith, Dennis Cluett and Arthur Bass. Recollections of a crew of World War II Lancaster Bomber called Mickey the Moocher Contents Introduction .............................................................................. 2 Abbreviations Used ................................................................... 3 Mickey the Moocher .................................................................. 5 Frank Mouritz ............................................................................ 7 No 5 Initial Training School, Clontarf .......................................................... 7 No 9 Elementary Flying Training School, Cunderdin .................................... 10 No 4 Service Flying Training School, Geraldton .......................................... 11 No 5 Embarkation Depot ......................................................................... 12 No 1 Embarkation Depot, Ascot Vale ......................................................... 13 At Sea .................................................................................................. 14 Across America ...................................................................................... 16 Crossing the Atlantic .............................................................................. 17 United Kingdom, First Stop Brighton ........................................................ -

Nation's Top Cybersecurity Program Leaps Forward with Infrastructure Investments to Advance Government–University–Industry

Nation’s top cybersecurity program leaps forward with infrastructure investments to advance Government–University–Industry partnerships in the interest of national security Leveraging Government-University-Industry Partnerships Governmental agencies are calling for greater collaboration to address America’s national security infrastructure protection. To encourage this, business and local government partners will have direct access to the technical expertise, highly trained students, and specialized facilities that make UTSA a premier cybersecurity program. The National Security Collaboration Center (NSCC) is the result of strong partnerships with both the public and private sectors. Current federal cyber operations in San Antonio Both virtual resources and a physical account for more than 7,000 military and civilian jobs. location are vital for government, industry, and academic partners to collaborate, UT San Antonio is partnering with the following: conduct leading research, and to rapidly develop and prototype state of the art · U.S. Army Research Laboratory technologies and solutions to face the ever- · National Security Agency (NSA) Texas increasing level of threats to national security and global defense. · 24th Air Force Cyber Command · 25th Air Force By partnering with the National Security (specializing in intelligence, surveillance Collaboration Center, companies will have and reconnaissance agency) a competitive advantage for attracting customers, talent, and funding to grow their Department of Homeland Security · businesses. With its convenient location, · U.S. Secret Service partners will have expedient access to UTSA faculty, research, and students and · Federal Bureau of Investigation have the benefit of competitively priced land, lab, and office space leases. The NSCC will be a 80,000 sq. ft./$33M facility supporting Government-University-Industry (GUI) partners. -

The Bombsight War: Norden Vs. Sperry

The bombsight war: Norden vs. Sperry As the Norden bombsight helped write World War II’s aviation history, The less-known Sperry technology pioneered avionics for all-weather flying Contrary to conventional wisdom, Carl three axes, and was often buffeted by air turbulence. L. Norden -- inventor of the classified Norden The path of the dropped bomb was a function of the bombsight used in World War I! -- did not acceleration of gravity and the speed of the plane, invent the only U.S. bombsight of the war. He modified by altitude wind direction, and the ballistics invented one of two major bombsights used, of the specific bomb. The bombardier's problem was and his was not the first one in combat. not simply an airborne version of the artillery- That honor belongs to the top secret gunner's challenge of hitting a moving target; it product of an engineering team at involved aiming a moving gun with the equivalent of Sperry Gyroscope Co., Brooklyn, N. Y. The a variable powder charge aboard a platform evading Sperry bombsight out did the Norden in gunfire from enemy fighters. speed, simplicity of operation, and eventual Originally, bombing missions were concluded technological significance. It was the first by bombardier-pilot teams using pilot-director bombsight built with all-electronic servo systems, so it responded indicator (PDI) signals. While tracking the target, the bombardier faster than the Norden's electromechanical controls. It was much would press buttons that moved a needle on the plane's control simpler to learn to master than the Norden bombsight and in the panel, instructing the pilot to turn left or right as needed. -

Avro Lancaster: the Survivors Free

FREE AVRO LANCASTER: THE SURVIVORS PDF Glenn White | 200 pages | 30 Dec 2010 | Mushroom Model Publications | 9788389450470 | English | Poland MMP Books » Książki Bureau of Aircraft Accidents Archives. Avro Lancaster. KB Read more about KB Type of aircraft: Avro Lancaster. Registration: B Flight Phase: Takeoff climb. Flight Type: Training. Survivors: Yes. Site: Airport less than 10 km from airport. MSN: Santa Cruz. Country: Argentina. Region: South America. Crew on board: 6. Pax on board: 0. Total fatalities: 0. Aircraft flight hours: Circumstances: Crashed during takeoff and came to rest in flames. All six crew members escaped uninjured. Registration: Flight Phase: Flight. Flight Type: Military. Survivors: No. Site: Plain, Valley. Schedule: Paris — Istres — Agadir. Marrakech-Tensift- El Haouz. Country: Morocco. Region: Africa. Crew on board: 5. Pax on board: Total fatalities: The airplane was also coded WU Probable cause: Engine fire in flight. Flight Type: Test. Schedule: Malmen - Malmen. Country: Sweden. Region: Europe. Crew on board: 4. Total fatalities: 2. Circumstances: The crew two pilots and two engineers were involved in a local Avro Lancaster: The Survivors flight following engine maintenance and modification. Shortly after takeoff from Malmen AFB, while climbing, the engine number one caught fire. Both engineers were able to bail out and were found alive while both pilots were killed when the aircraft crashed in a huge explosion in Slaka Kyrka, about 4 km south of the airbase. Probable cause: Loss of control during initial climb following fire on engine number one. Crash of an Avro Lancaster B. Registration: RE Schedule: Newquay - Newquay. Country: United Kingdom. The captain decided to abandon the takeoff procedure but as the aircraft started to skid, he raised the undercarriage, causing the aircraft to sink on runway and to slid for dozen yards before coming to rest. -

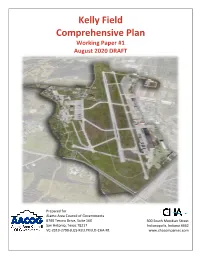

Kelly Field Comprehensive Plan Working Paper #1 August 2020 DRAFT

Kelly Field Comprehensive Plan Working Paper #1 August 2020 DRAFT Prepared for Alamo Area Council of Governments 8700 Tesoro Drive, Suite 160 300 South Meridian Street San Antonio, Texas 78217 Indianapolis, Indiana 4662 VC-2019-2790-JLUS-KELLYFIELD-CHA-R1 www.chacompanies.com KELLY FIELD (SKF) COMPREHENSIVE PLAN TABLE OF CONTENTS Kelly Field Executive Summary: National Airport, National Asset ................................................... I Introduction ........................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 Project Description ...................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Purpose and Objective ................................................................................................. 1-2 1.3 Kelly Field Background ................................................................................................. 1-2 1.3.1 History .......................................................................................................................... 1-3 1.3.2 Airport Organization and National Role ...................................................................... 1-4 1.3.3 Impact on National Defense ........................................................................................ 1-5 1.3.4 Annual Aircraft Operations .......................................................................................... 1-6 1.3.5 Surrounding Aviation Community .............................................................................. -

Advertising Brochure

Banners Advertising $ Price Listing JBSAtoday Magazine • $550 half page • $1,000 full page Posters • $1,200 inside front, inside back cover or back cover Digital Vinyl Banners: Displays • Cost based on size @ $8.50 per square foot, per month • Example: 4’ x 10’ banner equals 40 sq ft x $8.50 = $340 per month Primary POC for Advertising • Annual rate for advertising at one JBSA location- $1,620 (10% Direct discount) • Annual rate for advertising at all three JBSA locations- $4,320 (20% JBSA - Lackland: Advertising discount) Mr. Al Conyers Posters 22”w x 28”h: Vinyl banners, posters and table tents may be • Cost per location- $125 per poster, per month 210-925-1187 displayed at any of our high traffic facilities • Discounted monthly rate when advertised at all three locations- $120 [email protected] throughout JBSA. Those facilities include but are per poster per month • Annual rate for advertising at one JBSA location- $1,350 (10% not limited to three Bowling Centers, four 18-hole discount) championship Golf Courses, Fitness Centers, multiple • Annual rate for advertising at all three JBSA locations- $1,200 (20% Advertising Child and Youth Centers, a historic Theatre, three discount) Clubs, three Outdoor Recreation Centers, the Student Window Clings Activity Center on the METC campus at Fort Sam • Cost based on size @ $10.00 per square foot, per month Brochure • Example: 4’ x 10’ banner equals 40 sq ft x $8.50 = $340 per month Houston serving enlisted medical trainees and an • Annual rate for advertising at one JBSA location- $1,620 (10% Alternate POC’s Equestrian Center. -

Evolutionary Agent-Based Simulation of the Introduction of New Technologies in Air Traffic Management

Evolutionary Agent-Based Simulation of the Introduction of New Technologies in Air Traffic Management Logan Yliniemi Adrian Agogino Kagan Tumer Oregon State University UCSC at NASA Ames Oregon State University Corvallis, OR, USA Moffett Field, CA, USA Corvallis, OR, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT new piece of technology to fit into this framework is a challenging Accurate simulation of the effects of integrating new technologies process in which many unforeseen consequences. Thus, the abil- into a complex system is critical to the modernization of our anti- ity to simulate new technologies within an air traffic management quated air traffic system, where there exist many layers of interact- framework is of the utmost importance. ing procedures, controls, and automation all designed to cooperate One approach is to create a highly realistic simulation for the with human operators. Additions of even simple new technologies entire system [13, 14], but in these cases, every technology in the may result in unexpected emergent behavior due to complex hu- system must be modeled, and their interactions must be understood man/machine interactions. One approach is to create high-fidelity beforehand. If this understanding is lacking, it may be difficult human models coming from the field of human factors that can sim- to integrate them into such a framework [16]. With a sufficiently ulate a rich set of behaviors. However, such models are difficult to complex system, missed interactions become a near-certainty. produce, especially to show unexpected emergent behavior com- Another approach is to use an evolutionary approach in which a ing from many human operators interacting simultaneously within series of simple agents evolves a model the complex behavior of the a complex system. -

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron's

The Fighting Five-Tenth: One Fighter-Bomber Squadron’s Experience during the Development of World War II Tactical Air Power by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Auburn, Alabama December 14, 2013 Keywords: World War II, fighter squadrons, tactical air power, P-47 Thunderbolt, European Theater of Operations Copyright 2013 by Adrianne Lee Hodgin Bruce Approved by William Trimble, Chair, Alumni Professor of History Alan Meyer, Assistant Professor of History Mark Sheftall, Associate Professor of History Abstract During the years between World War I and World War II, many within the Army Air Corps (AAC) aggressively sought an independent air arm and believed that strategic bombardment represented an opportunity to inflict severe and dramatic damages on the enemy while operating autonomously. In contrast, working in cooperation with ground forces, as tactical forces later did, was viewed as a subordinate role to the army‘s infantry and therefore upheld notions that the AAC was little more than an alternate means of delivering artillery. When President Franklin Delano Roosevelt called for a significantly expanded air arsenal and war plan in 1939, AAC strategists saw an opportunity to make an impression. Eager to exert their sovereignty, and sold on the efficacy of heavy bombers, AAC leaders answered the president‘s call with a strategic air doctrine and war plans built around the use of heavy bombers. The AAC, renamed the Army Air Forces (AAF) in 1941, eventually put the tactical squadrons into play in Europe, and thus tactical leaders spent 1943 and the beginning of 1944 preparing tactical air units for three missions: achieving and maintaining air superiority, isolating the battlefield, and providing air support for ground forces.