Project Proposal for Ludali Farmers Association

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Concerns of Orphans and Development Association (Cocoda) P

COMMUNITY CONCERNS OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (COCODA) P. O. BOX 712, NJOMBE - CHAUNGINGI STREET ALONG SONGEA ROAD, OPPOSITE TANESCO REGIONAL OFFICE Email: [email protected] Website: www.cocoda.or.tz COCODA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT COMMUNITY CONCERN OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION REPORTING PERIOD: 1 JANUARY – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Projects Implemented Councils • SAUTI Project Njombe Region councils: Njombe Town Council • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA Project • • Njombe District Council • USAID Tulonge Afya • Makambako Town Council • Makete District Council • Wanging’ombe District Council • Ludewa District Council Prime Recipients Implementing Partners • DELOITTE CONSULTANCY LTD • LGAs JHPIEGO • • Health facilities • PACT TANZANIA • FHI360 Programme/Project Budget/Year Programme Duration • SAUTI 182,970,583 5 Years • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA 297,158,227 5 Years • USAID TULONGE AFYA 159,376,560 5 Years TOTAL: 639,505,370 Report Submitted By o Name: Mary Kahemele o Title: Executive Director o Organization: COCODA o Email address: [email protected] o Phone No: 0754 071 288 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms / Abbreviations ................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................................................... 5 I. SAUTI PROJECT ................................................................................................. -

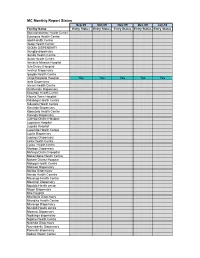

MC Monthly Report Status

MC Monthly Report Status Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Jan-10 Facility Name Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Bomalang'ombe Health Centre Bulongwa Health Centre Idodi Health Centre Ifwagi Health Center IGOMA DISPENSARY Ihungilo dispensary Ikonda Health Centre Ikuwo Health Centre Ilembula Mission Hospital Ilula District Hospital Imalinyi Dispensary Ipogolo Health Centre Iringa Regional Hospital Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Isele Dispensary Ismani Health Centre Itulahumba Dispensary Kasanga Health Centre Kibena Town Hospital Kidabaga Health Centre Kidugala Health Centre Kimande Dispensary Kiponzelo Health Centre Kisanga Dispensary Ludewa District Hospital Lugalawa Hospital Lugoda Hospital Lupembe Health Centre Lupila Dispensary Lupingu Dispensary Lwila Health Centre Lyasa Health centre Madege Dispensary Mafinga District Hospital Makambako Health Centre Makete District Hospital Makoga Health Centre Makowo Dispensary Maliwa Dispensary Manda Health Ceantre Mavanga Health Centre Mawengi Dispensary Mgololo Health center Migori Dispensary Milo Hospital Mtambula Dispensary Mtandika Health Centre Mtwango Dispensary Mundidi Health centre Mwatasi Dispensary Ngalanga dispensary Ngome Health Centre Nyombo Dispensary Nyumbanitu Dispensary Pomerini dispensary Sadani Health Center Saint Lukes Dispensary Tanangozi Dispensary TANWAT Hospital Tosamaganga District Hospital Ugwachanya Dispensary Ujuni Dispensary Ukalawa dispensary Uliwa Dispensary Usokami HC Key: Not Applicable Available Not Available Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania The United Republic of Tanzania Jointly prepared by Ministry of Finance and Planning, National Bureau of Statistics and Njombe Regional Secretariat Njombe Region National Bureau of Statistics Njombe Dodoma November, 2020 Njombe Region Socio-Economic Profile, 2018 Foreword The goals of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025 are in line with United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and are pursued through the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) or MKUKUTA II. The major goals are to achieve a high-quality livelihood for the people, attain good governance through the rule of law and develop a strong and competitive economy. To monitor the progress in achieving these goals, there is need for timely, accurate data and information at all levels. Problems especially in rural areas are many and demanding. Social and economic services require sustainable improvement. The high primary school enrolment rates recently attained have to be maintained and so is the policy of making sure that all pupils who passed Primary School Leaving Examination must join form one. The Nutrition situation is still precarious; infant and maternal mortality rates continue to be high and unemployment triggers mass migration of youths from rural areas to the already overcrowded urban centres. Added to the above problems, is the menace posed by HIV/AIDS, the prevalence of which hinders efforts to advance into the 21st century of science and technology. The pandemic has been quite severe among the economically active population leaving in its wake an increasing number of orphans, broken families and much suffering. AIDS together with environmental deterioration are problems which cannot be ignored. -

An End of Project Review for the Agro-Dealer Development Project Funded by Agra in Tanzania

AN END OF PROJECT REVIEW FOR THE AGRO-DEALER DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FUNDED BY AGRA IN TANZANIA FINAL REPORT Prepared by: Kobe Konsult Ltd JUED Business Centre, 34 Garden Road, Mikocheni A, P.O. Box 32187, Dar es Salaam Phone: +255 22 277 4436 / 0754 300 767 Fax: +255 22 277 4426 Email: [email protected] August 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES .................................................................................................................. iv LIST OF TABLES ...................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................................... vii Executive Summary ................................................................................................................ viii 1.0 INTRODUCTION................................................................................................................. 1 1.1 Background and Rationale ....................................................................................... 1 1.2 Evaluation Objectives and Scope ............................................................................. 1 1.2.1 Specific objectives ........................................................................................................ 2 2.0 METHODOLOGY AND APPROACH ............................................................................. 2 2.1 Review of Secondary Data ....................................................................................... -

Potentials of Agrarian Cluster Development for Improving Smallholder’S Income – a Case Study from the SAGCOT Initiative in Tanzania

_______________________________________________________________ Universität zu Köln Mathematisch-Naturwissenschaftliche-Fakultät Geographisches Institut Bachelorarbeit zur Erlangung des Grades „Bachelor of Science“ Potentials of Agrarian Cluster Development for Improving Smallholder’s Income – a case study from the SAGCOT initiative in Tanzania Veronika Charlotte Steffens Matrikelnummer: 5639913 [email protected] Richard-Wagner-Str. 22 Eingereicht am 21.11.2016 Erstgutachter: Prof. Dr. Peter Dannenberg 50181 Bedburg Zweitgutachter: Prof. Dr. Javier Revilla Diez Tel.: 0174 957 11 24 – 0 – . Table of Contents . LIST OF FIGURES ......................................................................................................... II LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS .......................................................................................... III 1 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 1 2 CONCEPTIONAL BACKGROUND: POTENTIALS OF CLUSTER-BASED DEVELOPMENT IN AGRICULTURE ............................................................................. 2 2.1 THE IDEA OF CLUSTER AND CLUSTER INITIATIVE – GENERAL DEFINITIONS ........................................ 2 2.2 CLUSTER-RELATED CONCEPTS FOR AGRICULTURAL AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT ............................... 4 2.3 TAKING THE CONCEPT TO THE GLOBAL SOUTH: CLUSTER DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMS IN AFRICA ... 6 2.4 FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSIS ........................................................................................................................ -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania POWER SYSTEM MASTER PLAN 2012 UPDATE Produced by: Ministry of Energy and Minerals May 2013 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AfDB African Development Bank BoT Bank of Tanzania CCM Chama Cha Mapinduzi COSS Cost of Service Study DSM Demand-side Management EAPMP East Africa Power Master Plan EEPCo Ethiopia Electric Power Company EPC Engineering, Procurement and Construction Contract ERT Energizing Rural Transformation ESKOM Electricity Supply Company (RSA) EWURA Energy and Water Utilities Regulatory Authority FYDP Five Years Development Plan GoT Government of the United Republic of Tanzania GWh Gigawatt-hours = 1,000,000,000 watt-hours GWh Gigawatt-hours = 1,000,000,000 watt-hours IDC Interest During Construction IPP Independent Power Producer IPTL Independent Power Tanzania Limited KPLC Kenya Power and Lighting Company kWh Kilowatt-hours = 1,000 watt-hours LTPP Long Term Plan Perspective MCA-T Millennium Challenge Account Tanzania MEM Ministry of Energy and Minerals MKUKUTA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi na Kupunguza Umasikini Tanzania MKUZA Mkakati wa Kukuza Uchumi Zanzibar MoF Ministry of Finance MPEE Ministry of Planning, Economy and Empowerment MPIP Medium-Term Public Investment Plan MVA Mega Volt Ampere MVAr Mega Volt Ampere Reactive MW Megawatt = 1000,000 watts MWh Megawatt-hours = 1,000,000 watt-hours NBS National Bureau of Statistics NDC National Development Corporation NGO Non-Governmental Organisations POPC President‘s Office Planning Commission PPA Power Purchase Agreement i PPP Public Private Partnership PSMP Power System Master Plan R&D Research and Development REA Rural Energy Agency REB Rural Energy Board REF Rural Energy Fund SADC Southern African Development Community SAPP South African Power Pool SEZ Special Economic Zone SME Small and Medium Enterprises SNC SNC-Lavalin International Inc. -

A Report on Avocado Value Chain Mapping in Siha And

A REPORT ON AVOCADO VALUE CHAIN MAPPING IN SIHA AND NJOMBE DISTRICTS May 20th, 2014 Prepared by Hebron A. Mwakalinga P.O. Box 78496, Dar es Salaam Phone : +255 786 171 000 E-mail: [email protected] Report on Avocado Value Chain Mapping in Siha and Njombe ACKNOWLGEMENT AND DISCLAIMER The Consultant thanks UNDP and MIT for awarding this interesting and important assignment of mapping avocado value chain in Siha and Njombe. It is important because of the potential the crop has in improving rural household incomes, foreign exchange earnings, nutrition to Tanzanians as well as environment protection. The Consultant team acknowledges the support received from UNDP and MIT staff namely Mr. Ernest Salla – Practice Specialist Trade/Private Sector Development, Mr Yona Shamo – Procurement Associate and Ms Irene Kajuna – Procurement Analyst. At the Ministry of Industry and Trade the work was supervised by SME Department Staff particularly Dr. Fidea Mgina – Assistant Director and Mr. Deogratius Sangu – Trade Officer who also accompanied the team in the field. In Kilimanjaro we acknowledge RAS staff namely Mr. Simon Msoka and Frederick Mushi for their assistance in gathering production data from District Councils and Mr. Frederick Mushi for participating at the Siha’s stakeholders’ workshop. At Siha the Acting District Executive Director Mr. Jonas P. Moses is thanked by the Team for gracing the workshop. Special appreciations go to Mr. A. Siayo Agriculture Officer who coordinated all field activities in Siha. In Njombe special thanks are extended to Njombe Regional Commissioner Captain A. G. Msangi who dedicated about two hours of his precious time for consultation with the study team, alongside the Regional Commissioner were the Assistant RAS – Productive Sector Mr. -

Makambako Town Council Strategic Plan 2016/17-2020/21

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT MAKAMBAKO TOWN COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN 2016/17-2020/21 Prepared by: Town Director’s Office Makambako Town Council P O BOX 405, Makambako, Tanzania Tel: 026- 2773004 Fax 026- 27730445 Email: [email protected] August, 2016 i Contents LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................................... iv Definition of terms ........................................................................................................................................... vi Message from his Honorary the Chairman ................................................................................................ viii Forward by Town Director ............................................................................................................................ ix Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ xi CHAPTER ONE -INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Socio-Economic Development ................................................................................................. 2 1.3 Methodology ......................................................................................................................... -

VIPAJI NJOMBE MKOA.Xlsx

MKOA WA NJOMBE ORODHA YA WANAFUNZI WALIOCHAGULIWA KUJIUNGA NA SHULE ZA SEKONDARI KIDATO CHA KWANZA JANUARI 2020 A: SHULE ZA BWENI 1.UFAULU MZURI (SPECIAL SCHOOLS) I: WAVULANA PReM NAMBA YA SHULE SHULE HALMASHAURI NA JINA LA MTAHINIWA NUMBER MTAHINIWA ATOKAYO AENDAYO ATOKAYO 1 20171374982 PS2603032-039 JONATHAN VALENTINO NDEDELA SIGRID KIBAHA MJI MAKAMBAKO 2 20171375004 PS2603033-038 YOHANA JANKE SANGA UHURU KIBAHA MJI MAKAMBAKO 3 20130910264 PS2604077-001 ADAMU GERALD MAGAGA MT BAKITA KIBAHA MJI NJOMBE 4 20130910505 PS2604079-002 BRAITON KANUTH MSEMWA ST DONBOSCO KIBAHA MJI NJOMBE 5 20130966305 PS2601104-009 JOSEPH JERMANUS MGANWA MAMALILO KIBAHA LUDEWA 6 20130966300 PS2601104-004 CLINTON MUSSA MHINA MAMALILO KIBAHA LUDEWA 7 20130316694 PS2606019-004 ANTELMO INONCENT CHAMANGE IGWACHANYA KIBAHA WANGING'OMBE 8 20130763996 PS2602066-008 ETHNOS METHOD MLOWE MFUMBI KIBAHA MAKETE 9 20130327956 PS2606012-013 DIKSON JOSEPH MDUGO IGELEHEDZA KIBAHA WANGING'OMBE 10 20130260830 PS2605058-016 NICK KELVIN MTANGA ITUNDUMA KIBAHA NJOMBE VIJIJINI 2. SHULE ZA SEKONDARI UFUNDI PReM NAMBA YA SHULE SHULE HALMASHAURI NA JINA LA MTAHINIWA NUMBER MTAHINIWA ATOKAYO AENDAYO ATOKAYO 1 20171039562 PS2603033-037 TONINO IGNASI KIBIKI UHURU IFUNDA TECH MJI MAKAMBAKO 2 20130910267 PS2604077-003 ALFA DAWI YAEDA MT BAKITA IFUNDA TECH MJI NJOMBE 3 20130910272 PS2604077-006 BRIGHT CHARLES MFUNTA MT BAKITA IFUNDA TECH MJI NJOMBE 4 20171374986 PS2603032-044 KELLY VALENCE MKULA SIGRID IYUNGA TECH MJI MAKAMBAKO 5 20130909200 PS2604077-005 BONAVENTURE YERONIMUS KISWAGA MT BAKITA -

Evaluation of the Bringing Nutrition to Scale Project in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe

Evaluation of the Bringing Nutrition to Scale Project in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe Regions (2013–2017) Evaluation Report 23 April 2018 Prepared by Stephen Turner (Team Leader) Bjorn Ljungqvist Joyce Kinabo Jim Grabham Proposal contacts: Evaluation of Bringing Nutrition to Scale in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DISCLAIMER The evaluation team are grateful to the nutrition colleagues at the UNICEF Country Office in Dar es Salaam and the Sub-office in Mbeya for all their support in providing information and facilitating meetings throughout this assignment. Quality support for the evaluation has been provided by the QS team assigned to the evaluation: Stephen Anderson (Food Economy Group) and Stephen Lister (Mokoro Ltd). The authors take full responsibility for the contents of this report. The designations employed, maps and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNICEF concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. ii Evaluation of Bringing Nutrition to Scale in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe Contents Summary v 1. Introduction __________________________________________________ 1 1.1. Evaluation purpose and scope ___________________________________ 1 1.2. Country context ______________________________________________ 1 1.3. Nutrition in Tanzania and the project area __________________________ 2 2. The BNTS and ASRP projects _____________________________________ 5 2.1. Project description ____________________________________________ 5 2.2. Key stakeholders and linkages ___________________________________ 8 2.3. Summary of reported performance ______________________________ 10 3. Approach and methods _________________________________________ 11 3.1. Evaluation approach __________________________________________ 11 3.2. -

Annual Report 2013 Table of Contents

SHIPO Annual Report 2013 Table of contents Abbreviations 1 The Board Chairperson’s foreword 2 Program Manager’s foreword 2 Intoduction 3 Where we work 5 The Board 6 Organisation achievements for 2013 7 Water Supply and Management, Hygiene and Sanitation 8 Education and Health 10 Home Based Care 12 SHIPO SMART Training Centre 14 CSR solutions for big companies 15 Independence Torch 16 Donors and Funding 17 Financial Performances 19 Network and alliances 20 Human Resources 21 Contacts 23 Abbriviations ACRA Asociación de Cooperación Rural en Africa CBO Community Based Orgasation CI Connect International COWSO Community Owned Water Supply Organisation CSO Civil Society Organizations CSR Corporate Social Responsibility GRL Green Resources Limited LRTT Limited Resources Teacher Training NGO Non Governmental Organization NJODINGO Njombe District Non Governmental Organization OVC Orphans and Vulnerable Children O&OD Obstacles and Opportunity to Development RWSN Rural Water Supply Network SACCOS Savings and Credit Cooperatives Societies. SHIPO Southern Highlands Participatory Organization SIDO Small-scale Industries Development Organization SMART Sustainable, Market based, Affordable and Reliable Technology SNV Netherlands Development Organization SWASH School Water, Sanitation and Hygiene TAWASANET Tanzania Water and Sanitation Network TLM Teaching and Learning Materials TZS Tanzanian Shillings VAG Village Action Groups WASH Water, Sanitation and Hygiene VETA Vocational Education and Training Authority WDMI Water Development and Management Institute of Tanzania 1 Foreword Board Chairperson’s foreword The Millennium Development Goals (MDG) has been guiding beacons for develop- ment for the past Decade. 2015 is the final year for implementation of the targets set down more than 10 years ago. As an organization, SHIPO has been striving to contrib- ute to reach the MDGs, especially MDG number one being; halve the proportion of people living below the national poverty line by 2015. -

A Brief Report on Potato Production in Njombe Region

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT A BRIEF REPORT ON POTATO PRODUCTION IN NJOMBE REGION Prepared by: Regional Commissioner’s Office P. O Box 668 NJOMBE Tel No: (026) 2782912 E-mail: [email protected] [email protected] 1 A REPORT ON POTATO PRODUCTION IN NJOMBE REGION 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Regional Profile The region is located in Southern Highlands Zone which comprises of Ruvuma, Iringa, Mbeya, Rukwa, Katavi and Njombe Regions. It borders Iringa Region in the north, Morogoro Region in the east and Ruvuma region in the south. The Republic of Malawi via Lake Nyasa and part of Mbeya Region borders Njombe Region in the south-west, while in the west the borders are shared with Mbeya Region again. The region lies between latitude 08o 50’ and 10o 30’ south of the equator and between longitude 33o 45’ and 35o 45’ east of Greenwich. Njombe region has an area of 24,994 km2 and is divided into four Administrative Districts (Makete, Njombe, Ludewa and Wanging’ombe) and six Local Government Authorities (Njombe DC, Njombe TC, Makambako TC, Makete DC, Ludewa DC and Wanging’ombe DC). 1. 2 Administration Table 1: Distribution of Administrative Units by Councils District Division Wards Villages Streets/sub villages Njombe TC 2 13 44 26 Njombe DC 2 12 45 219 Ludewa DC 5 25 77 337 Makete DC 6 22 97 467 Wanging’ombe 3 21 108 446 DC Makambako TC 1 12 14 54 Total 19 105 385 1,549 1.3 Population According to the census of 2012 the population of Njombe Region is 702,097 people (329, 593 males and 372,738 females).