Evaluation of the Bringing Nutrition to Scale Project in Iringa, Mbeya and Njombe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

USAID Tanzania Activity Briefer May 2020

TANZANIA ACTIVITY BRIEFER MAY 2020 For over five decades, the United States has partnered with the people of Tanzania to advance shared development objectives. The goal of USAID assistance is to help the country achieve self- reliance by promoting a healthy, prosperous, democratic, well- governed, and secure Tanzania. Through partnerships and investments that save lives, reduce poverty, and strengthen democratic governance, USAID’s programs advance a free, peaceful, and prosperous Tanzania. In Tanzania, USAID engages in activities across four areas: ● Economic growth, including trade, agriculture, food security, and natural resource management ● Democracy, human rights, and governance ● Education ● Global health LARRIEUX/ USAID ALEX ALEX ECONOMIC GROWTH OVERVIEW: USAID supports Tanzania’s economic development and goal to become a self-reliant, middle- income country by 2025. We partner with the government and people of Tanzania, the private sector, and a range of development stakeholders. Agriculture plays a vital role in Tanzania’s economy, employing 65 percent of the workforce and contributing to nearly 30 percent of the economy. USAID strengthens the agriculture policy environment and works directly with actors along the production process to improve livelihoods and trade. At the same time, we strengthen the ability of rural communities to live healthy, productive lives through activities that improve 1 nutrition and provide access to clean water and better sanitation and hygiene. We also enhance the voices of youth and women in decision making by building leadership skills and access to assets, such as loans and land ownership rights. As Tanzania’s natural resources are the foundation for the country’s development, we work to protect globally important wildlife, remarkable ecosystems, and extraordinary natural resources. -

Community Concerns of Orphans and Development Association (Cocoda) P

COMMUNITY CONCERNS OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION (COCODA) P. O. BOX 712, NJOMBE - CHAUNGINGI STREET ALONG SONGEA ROAD, OPPOSITE TANESCO REGIONAL OFFICE Email: [email protected] Website: www.cocoda.or.tz COCODA 2019 ANNUAL REPORT COMMUNITY CONCERN OF ORPHANS AND DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION REPORTING PERIOD: 1 JANUARY – 31 DECEMBER 2019 Projects Implemented Councils • SAUTI Project Njombe Region councils: Njombe Town Council • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA Project • • Njombe District Council • USAID Tulonge Afya • Makambako Town Council • Makete District Council • Wanging’ombe District Council • Ludewa District Council Prime Recipients Implementing Partners • DELOITTE CONSULTANCY LTD • LGAs JHPIEGO • • Health facilities • PACT TANZANIA • FHI360 Programme/Project Budget/Year Programme Duration • SAUTI 182,970,583 5 Years • USAID KIZAZI KIPYA 297,158,227 5 Years • USAID TULONGE AFYA 159,376,560 5 Years TOTAL: 639,505,370 Report Submitted By o Name: Mary Kahemele o Title: Executive Director o Organization: COCODA o Email address: [email protected] o Phone No: 0754 071 288 1 Table of Contents List of Acronyms / Abbreviations ................................................................................ 3 Executive Summary ................................................................................................... 4 PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION ..................................................................................... 5 I. SAUTI PROJECT ................................................................................................. -

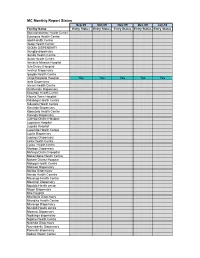

MC Monthly Report Status

MC Monthly Report Status Sep-09 Oct-09 Nov-09 Dec-09 Jan-10 Facility Name Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Entry Status Bomalang'ombe Health Centre Bulongwa Health Centre Idodi Health Centre Ifwagi Health Center IGOMA DISPENSARY Ihungilo dispensary Ikonda Health Centre Ikuwo Health Centre Ilembula Mission Hospital Ilula District Hospital Imalinyi Dispensary Ipogolo Health Centre Iringa Regional Hospital Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Isele Dispensary Ismani Health Centre Itulahumba Dispensary Kasanga Health Centre Kibena Town Hospital Kidabaga Health Centre Kidugala Health Centre Kimande Dispensary Kiponzelo Health Centre Kisanga Dispensary Ludewa District Hospital Lugalawa Hospital Lugoda Hospital Lupembe Health Centre Lupila Dispensary Lupingu Dispensary Lwila Health Centre Lyasa Health centre Madege Dispensary Mafinga District Hospital Makambako Health Centre Makete District Hospital Makoga Health Centre Makowo Dispensary Maliwa Dispensary Manda Health Ceantre Mavanga Health Centre Mawengi Dispensary Mgololo Health center Migori Dispensary Milo Hospital Mtambula Dispensary Mtandika Health Centre Mtwango Dispensary Mundidi Health centre Mwatasi Dispensary Ngalanga dispensary Ngome Health Centre Nyombo Dispensary Nyumbanitu Dispensary Pomerini dispensary Sadani Health Center Saint Lukes Dispensary Tanangozi Dispensary TANWAT Hospital Tosamaganga District Hospital Ugwachanya Dispensary Ujuni Dispensary Ukalawa dispensary Uliwa Dispensary Usokami HC Key: Not Applicable Available Not Available Feb-10 Mar-10 Apr-10 May-10 Jun-10 Jul-10 -

SAGCOT) Public Disclosure Authorized Investment Project

THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRIME MINISTER’S OFFICE Public Disclosure Authorized Southern Agricultural Growth Corridor of Tanzania (SAGCOT) Public Disclosure Authorized Investment Project SRATEGIC REGIONAL ENVIRONMENTAL Public Disclosure Authorized AND SOCIAL ASSESSMENT (SRESA) This SRESA report was prepared for the Government of Tanzania by Environmental Resources Management Limited (ERM) under a contract as part of SAGCOT preparatory activities Public Disclosure Authorized DECEMBER 2013 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY I 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 BACKGROUND 1 1.2 PROGRAMMEOVERVIEW 1 1.3 STUDY OBJECTIVE 2 1.4 PURPOSE OF THIS REPORT 3 1.5 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3 1.5.1 Overview 3 1.5.2 Screening 4 1.5.3 Scoping 4 1.5.4 Baseline Description 4 1.5.5 Scenario Development 4 1.5.6 Impact Assessment 5 1.5.7 Development of Mitigation Measures 5 1.5.8 Consultation 6 1.5.9 Constraints and Limitations 6 1.6 REPORT LAYOUT 6 2 THE SOUTHERN AGRICULTURAL GROWTH CORRIDOR OF TANZANIA 8 2.1 THE SAGCOT PROGRAMME 8 2.1.1 The SAGCOT Concept 8 2.1.2 SAGCOT Organisation 11 2.2 PROPOSED WORLD BANK SUPPORTED SAGCOT INVESTMENT PROJECT 14 2.2.1 General 14 2.2.2 Catalytic Fund 15 2.2.3 Support Institutions 16 3 THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR IN TANZANIA 20 3.1 INTRODUCTION 20 3.2 AGRICULTURE AND THE TANZANIAN ECONOMY 20 3.2.1 Overview 20 3.2.2 Land Use 25 3.3 PRIORITIES FOR DEVELOPMENT OF THE AGRICULTURE SECTOR 25 3.3.1 Current Initiatives for Agricultural Development 25 3.3.2 Rationale for SAGCOT Programme 29 3.3.3 District Level Agricultural Planning 30 3.4 FINANCING POLICIES -

Bringing Nutrition Actions to Scale in Iringa, Njombe and Mbeya Regions of Tanzania

Bringing Nutrition Actions to Scale in Iringa, Njombe and Mbeya Regions of Tanzania In-depth analysis of the factors associated with stunting Joint research study Concern Worldwide and Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (UCL) Study Report version 3 October 2015 Table of Contents 1 Introduction .................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Short review on stunting .................................................................................................................. 1 3 Methods .......................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1 Study area ................................................................................................................................ 2 3.2 Survey procedure ..................................................................................................................... 3 3.3 Data management ................................................................................................................... 3 3.4 Data analysis ............................................................................................................................ 6 3.4.1 Methodology part 1 – determinants of stunting ............................................................... 6 3.4.2 Methodology part 2 – focus on IYCF ................................................................................. 6 4 Results -

Iringa-Summary-Brief-Final.Pdf

STRATEGIC AssEssMENT TO DEFINE A COMPREHENSIVE RESPONSE TO HIV IN IRINGA, TANZANIA RESEARCH BRIEF SUMMARY OF FINDINGS STRATEGIC ASSESSMENT TO DEFINE A COMPREHENSIVE RESPONSE TO HIV IN IRINGA, TANZANIA RESEARCH BRIEF SUMMARY OF FINDINGS September 2013 The USAID | Project SEARCH, Task Order No.2, is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development under Contract No. GHH-I-00-07-00032-00, beginning September 30, 2008, and supported by the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief. The Research to Prevention (R2P) Project is led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Global Health and managed by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Communication Programs (CCP). Iringa Strategic Assessment: Summary of Findings TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .............................................................................................................. 2 INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................................... 3 METHODS ............................................................................................................................ 5 Quantitative Methods .................................................................................................................................. 5 Review of existing data including recent data triangulation efforts ........................................................... 5 DHS analysis ............................................................................................................................................... -

Il UNITED REPUBLIC of TANZANIA IMPLEMENTATION of WATER

Il UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA IATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY DANIDA 824 TZ.IR 85 IMPLEMENTATION OF WATER MASTER PLANS FOR IRINGA, RUVUMA AND MBEYA REGIONS HYDROLOGY - LOW FLOW GAUGINGS 1984 CARL BRO • COWiCONSULT • KAMPSAX - KRLJGER «CCKK I UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DANISH INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT AGENCY DANIDA IMPLEMENTATION OF WATER MASTER PLANS FOR IRINGA, RUVUMA AND MBEYA REGIONS HYDROLOGY - LOW FLOW GAUGINGS 1984 0 LIBRARY, INTERNA n:-NA-,. 1 : ! T .- i- iu/O -; j )] G.-.f. 141/14 L.G: CARL BRO • COWICONSULT • KAMPSAX - KRLJGER «CCKK I I I LOW FLOW STUDIES IN IRINGA, MBEYA AND RUVUMA REGIONS, TANZANIA I TABLE OF CONTENTS I Page 1. INTRODUCTION 1 I 2. DESCRIPTION OF FIELD WORK 2 m 2.1 Low Flow Measurements 2 2.2 Network Station Visits 3 3. DATA ANALYSES 4 I 4. VILLAGE WATER DEMAND VERSUS AVAILABILITY 16 I 5. CORRELATION ANALYSIS 29 I 6. CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS 32 I APPENDIX 1 I I I I I I I I I I I I 1. INTRODUCTION The aim of the low flow study is to provide the best possible estimates I of the 10-year minimum flows at the selected sources of the village water supply schemes. Such estimates will form the basis for the final I design of the individual water supplies and for additional source I investigations where selected sources do not have sufficient yields. The low flow measurement programme was conducted during the months of September, October and November 1984. Two measurements were made at I most of the selected sites with approximately one month lag-time between them. -

United Republic of Tanzania

United Republic of Tanzania The United Republic of Tanzania Jointly prepared by Ministry of Finance and Planning, National Bureau of Statistics and Njombe Regional Secretariat Njombe Region National Bureau of Statistics Njombe Dodoma November, 2020 Njombe Region Socio-Economic Profile, 2018 Foreword The goals of Tanzania’s Development Vision 2025 are in line with United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and are pursued through the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP) or MKUKUTA II. The major goals are to achieve a high-quality livelihood for the people, attain good governance through the rule of law and develop a strong and competitive economy. To monitor the progress in achieving these goals, there is need for timely, accurate data and information at all levels. Problems especially in rural areas are many and demanding. Social and economic services require sustainable improvement. The high primary school enrolment rates recently attained have to be maintained and so is the policy of making sure that all pupils who passed Primary School Leaving Examination must join form one. The Nutrition situation is still precarious; infant and maternal mortality rates continue to be high and unemployment triggers mass migration of youths from rural areas to the already overcrowded urban centres. Added to the above problems, is the menace posed by HIV/AIDS, the prevalence of which hinders efforts to advance into the 21st century of science and technology. The pandemic has been quite severe among the economically active population leaving in its wake an increasing number of orphans, broken families and much suffering. AIDS together with environmental deterioration are problems which cannot be ignored. -

United Republic of Tanzania President’S Office Regional Administration and Local Government

UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA PRESIDENT’S OFFICE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATION AND LOCAL GOVERNMENT WANGING’OMBE DISTRICT COUNCIL COUNCIL STRATEGIC PLAN FOR THE YEAR 2015/16 – 2019/20 Prepared by, District Executive Director, Wanging’ombe District Council, P.O.Box 64, WANGING’OMBE – NJOMBE REGION EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Wanging’ombe is a relatively newly established District council which was officially registered on 18, March, 2013. Like any other Council in Tanzania, Wanging’ombe district council operates with statutory powers and in line with legislation and regulations enacted by the parliament under the Local Government Act No. 7 of 1982. The council is given wide-ranging functions include: To maintain and facilitate the maintenance of peace, order and good governance in their area of jurisdiction, To promote the social welfare and economic well-being of all persons within its area of jurisdiction; Subject to the national policy and plans for the rural and urban development, to further the social and economic development of its area of jurisdiction. In fulfilling the Wanging’ombe district council’s functions, the district requires a comprehensive decision making to trigger sustainable local economic development through strategic planning at local level. This strategic plan will assist the District council to improve performance, to create more relevant institutional structures, to increase levels of institutional, departmental, and individual accountability; to improve transparency and communication between management, employees and stakeholders and to establish priorities for efficient and effective use of resource. This strategic plan document is divided into Five Chapters, where first chapter provides background information and strategic planning process, second chapter provides situational analysis of the district where a through diagnosis of the internal environment in 19 service areas was conducted, as well as the external environment which the district is operating under in executing this strategic plan. -

1.0. Introduction

FERTILITY LEVELS AND PATTERNS AMONG HIV-INFECTED AND UN-INFECTED WOMEN IN KYELA DISTRICT A CASE STUDY FROM TANZANIA. 1.0. Introduction The fertility transition, seen in many parts of the world, has been slow to start in Sub-Saharan Africa, although recent evidence suggests a moderate of fertility in few countries (UNAIDS, 2003). It is not clear how the HIV epidemic will alter future levels of fertility and what impact it will have on the nature of fertility transition. The contribution of HIV/AIDS to the fertility transition is not currently evident due to the fact that. For four reasons. First, isolating the factor of HIV/AIDS from other factors of fertility is a complex process because it is not a proximate variable, but one of the contributors to several proximate determinants of fertility. Secondly, for the impact of the epidemic to be felt, the prevalence has to be high in the region of 20 percent and be sustainable for a long time, about a decade or longer. Thirdly, behavior factors may reduce fertility of women with symptoms of AIDS, but not those asymptomatic. Fourthly, as infant mortality increases, the need to replace dead children and produce more to ensure survival of some will challenge implementation of family planning programmes in Sub-Saharan Africa and perhaps increase fertility. Also, increasing HIV prevalence in the region will mean that HIV/AIDS programmes will compete for resources with family planning progrmmes, which would weaken the latter (UNAIDS, 2003). Recent studies in Sub Saharan Africa have shown that fertility is reduced among HIV infected women compare with uninfected women. -

Ileje SP FULL

PREFACE Ileje District Council has a vital role of ensuring that effective coordination and supervision of service delivery Targets is in place so that stakeholders deliver quality services to the community and practice good governance in the development of the District. In order to achieve the above Strategic Objective, Ileje District Council through its Departments will strengthen its cooperation with all stakeholders through the existing government machinery. It will make sure that the policies are properly translated and implemented by her stakeholders in order to achieve sustainable development. The Medium Term Strategic Plan (MTSP) for the Ileje District Council (IDC) 2017/2018 - 2020/2021 is aimed at building the capacity of the Council and its stakeholders towards promoting economic growth with consequent poverty reduction among the local communities, with due emphasis. Ileje District Council will ensure that the set key result areas, strategic objectives and strategies are effectively implemented and monitored. Stakeholder shall be called upon to cooperate in the implementation of the District’s Strategic Plan. Therefore Government, Development Partners and Community are urged to give their maximum contribution and support according to their commitments in order to facilitate execution of the Council Medium Term Strategic Plan. Success in implementing the service delivery targets and strategic objectives of Ileje District Council will contribute greatly to the overall success in the achievement of National goals by improving its economy and reduce poverty among the population. ___________________ Ubatizo J. Songa DISTRICT CHAIRERSON, ILEJE. i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This Strategic Plan for 2017/2018 – 2020/2021 has been prepared in collaboration with a number of individuals and institutions including District and Ward political leaders, Council staff, Ward Executive Officers and Extension Staff, representatives from Public Institutions, Business Community and the Media. -

Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania I Design and Layout By: Jenna Park [email protected] TABLE of CONTENTS

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized ACCELERATING MINI- GRID DEPLOYMENT IN SUB-SAHARAN AFRICA Lessons from Tanzania Public Disclosure Authorized LILY ODARNO, ESTOMIH SAWE, MARY SWAI, MANENO J.J. KATYEGA AND ALLISON LEE Public Disclosure Authorized WRI.ORG Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania i Design and layout by: Jenna Park [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Foreword 3 Preface 5 Executive Summary 13 Introduction 19 Overview of Mini-Grids in Tanzania 39 The Institutional, Policy, and Regulatory Framework for Mini-Grids in Tanzania 53 Mini-Grid Ownership and Operational Models 65 Planning and Securing Financing for Mini-Grid Projects 79 How Are Mini-Grids Contributing to Rural Development? 83 Conclusions and Recommendations 86 Appendix A: People Interviewed for This Report 88 Appendix B: Small Power Producers That Signed Small Power Purchase Agreements and Submitted Letters of Intent 90 Appendix C: Policies, Strategies, Acts, Regulations, Technical Standards, and Programs, Plans, and Projects on Mini-Grids 94 Abbreviations 95 Glossary 96 Bibliography 99 Endnotes Accelerating Mini-Grid Deployment in Sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from Tanzania iii iv WRI.org FOREWORD More than half of the 1 billion people in the world In Tanzania, a slow environmental clearance without electricity live in Sub-Saharan Africa, procedure delayed the deployment of some mini- and rapid population growth is projected to grids despite a streamlined regulatory process. outpace electric grid expansion. For communities across the region, a consistent and affordable Invest in both qualitative and quantitative ▪ supply of electricity can open new possibilities for assessments of the development impacts socioeconomic progress.