GIPE-004879.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Suggested Blueprint for the Development of Maritime Archaeological Research in Namibia Bruno E.J.S

Journal of Namibian Studies, 2 (2007): 103–121 ISSN: 1863-5954 A suggested blueprint for the development of maritime archaeological research in Namibia Bruno E.J.S. Werz Abstract During the last few decades, maritime archaeology has developed into an internationally accepted field of specialisation within the discipline of archaeology. It has, however, only gained academic recognition in Southern Africa since the late 1980s, when a lecturing post for maritime archaeology was established at the University of Cape Town. This resulted in initial efforts being focused on South Africa. Now, however, the time has come to expand the development of maritime archaeology to neighbouring countries. Due to various positive factors – including the presence of an important research potential as well as growing interest and positive contributions by some organisations and private individuals – Namibia provides a fertile ground to extend the field of operations. This article first summarises the objectives and methodology of maritime archaeological research in general; then it offers suggestions as to how to establish this research specialisation in Namibia, bearing in mind local circumstances. What is Maritime Archaeology? Maritime archaeology developed by means of an evolutionary process from underwater salvage, treasure hunting, the collecting of antiquities and the kind of archaeological work that was done until the early twentieth century. During the 1960s, the field became an area of specialisation within the discipline of archaeology. This period saw a growing involvement of professional archaeologists, the rudimentary development of research designs, the improvement of diving equipment, and the application of techniques that facilitated work in an underwater environment. The initial emphasis, however, was on the latter.1 As a result, the field did not obtain widespread support from its terrestrial counterparts, where efforts were generally directed at solving specific research problems. -

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Environmental Management Programme Report for the Development of the Kudu Gas Field on the Continental Shelf of Namibia

CSIR REPORT: CSIR/NRE/ECO/2005/0004/C ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE KUDU GAS FIELD ON THE CONTINENTAL SHELF OF NAMIBIA Prepared for: ENERGY AFRICA KUDU LIMITED Prepared by: P D Morant CSIR NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT P O Box 320 Stellenbosch 7599 South Africa Tel: +27 21 888 2400 Fax: +27 21 888 2693 Keywords: Namibia Hydrocarbon production Coast Offshore Environmental management programme JUNE 2006 ENERGY AFRICA KUDU LIMITED ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE KUDU GAS FIELD ON THE CONTINENTAL SHELF OF NAMIBIA SCOPE The CSIR’s Natural Resources and Environment Unit was commissioned by Energy Africa Kudu Limited to provide an environmental management programme report (EMPR) for the development and operation of the Kudu gas field on the southern Namibian continental shelf. The EMPR is based on the environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the development of the Kudu gas field (CSIR Report ENV-S-C 2004-066, December 2004 plus Addendum, December 2005). The EMPR includes an updated description of the project reflecting the finally selected design and a re-assessment of the resulting environmental impacts. The EMPR includes: An overview of the project and various component activities which may have an impact on the environment; A qualitative assessment of the various project actions on the marine and coastal environment of southern Namibia; A management plan to guide the implementation of the mitigation measures identified in the EIA. The format of the EMPR is modelled on the South African Department of Minerals and Energy’s Guidelines for the preparation of Environmental Management Programme Reports for prospecting for and exploitation of oil and gas in the marine environment, Pretoria 1996. -

Southwest Coast of Africa

PUB. 123 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ SOUTHWEST COAST OF AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2012 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2012 THIRTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface 0.0 Pub. 123, Sailing Directions (Enroute) Southwest Coast of date of the publication shown above. Important information to Africa, Thirteenth Edition, 2012, is issued for use in conjunc- amend material in the publication is available as a Publication tion with Pub. 160, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) South Data Update (PDU) from the NGA Maritime Domain web site. Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean. The companion volume is Pubs. 124. 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website 0.0 Digital Nautical Chart 1 provides electronic chart coverage http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 18 August 2012, in- 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same cluding Notice to Mariners No. 33 of 2012. manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- Explanatory Remarks igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the designated course. Vessels following the directives must allow 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department and navigate so that the designated course is continuously be- of Defense Directive 5105.40, dated 12 December 1988, and ing made good. -

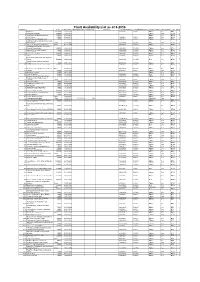

Chart Availability List As of 8-2016

Chart Availability List as of 8-2016 Number Title Scale Edition Date Withdrawn Date Replaced By Replaces Last NM Number Last NM Week-Year Product Status ARCS Chart Folio Disk 2 British Isles 1500000 23.07.2015 325\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF6 2 3 Chagos Archipelago 360000 21.06.2012 - Edition Yes BF38 5 5 `Abd Al Kuri to Suqutra (Socotra) 350000 07.03.2013 - Edition Yes BF32 5 6 Gulf of Aden 750000 26.04.2012 124\2015 1-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 7 Aden Harbour and Approaches 25000 31.10.2013 452\2016 3-2016 Edition Yes BF32 5 La Skhirra-Gabes and Ghannouch with 9 Approaches Plans 24.10.1986 1578\2014 14-2014 New Yes BF24 4 11 Jazireh-Ye Khark and Approaches Plans 03.12.2009 4769\2015 37-2015 Edition Yes BF40 5 Al Aqabah to Duba and Ports on the 12 Coast of Saudi Arabia 350000 14.04.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 13 Approaches to Cebu Harbour 35000 21.04.2011 3428\2014 31-2014 Edition Yes BF58 6 14 Cebu Harbour 12500 17.01.2013 4281P\2015 33-2015 Edition Yes BF58 6 15 Approaches to Jizan 200000 17.07.2014 105\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 16 Jizan 30000 19.05.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 Plans of the Santa Cruz and Adjacent 17 Islands 500000 14.08.1992 2829\1995 33-1995 New Yes BF68 7 Falmouth Inner Harbour Including 18 Penryn 5000 20.02.2014 5087\2015 40-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 20 Ile d'Ouessant to Pointe de la Coubre 500000 22.08.2013 419\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF16 1 26 Harbours on the South Coast of Devon Plans 17.04.2014 5726\2015 45-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 27 Bushehr 25000 15.07.2010 984\2016 7-2016 Edition Yes -

Forzamiento De Flujos Ageostróficos. Mar De

FORZAMIENTO DE FLUJOS AGEOSTRÓFICOS. MAR DE ALBORÁN Y PLATAFORMA DE MALLORCA-CABRERA Memoria para la obtención del título de doctor en Ciencias Físicas de: s Alvaro Viudez Lomba VOLUMEN I: TEXTO Universitat de les liles Balears Junio de 1994 Forzamiento de flujos ageostróficos. Mar de Alborán y plataforma de Mallorca-Cabrera. Memoria para la obtención del título de Doctor en Ciencias Físicas de: Alvaro Viudez Lomba Director: Dr. Joaquín Tintoré Subirana VOLUMEN I: TEXTO Universitat de les Ules Balears Junio de 1994 A mis padres, por su generosidad. Prólogo El contenido básico de la presente memoria de tesis doctoral, dirigida por el Dr. Joaquín Tintoré, está formado por un conjunto de artículos de Oceano grafía Física elaborados desde 1991 en colaboración con otros investigadores. El primer capítulo sitúa e introduce, desde la perspectiva general de la Oceanografía Física, los diversos trabajos que forman esta tesis. El segundo capítulo, cuyo principal autor es el Dr. Francisco E. Werner, es básicamente un estudio numérico de la circulación en la plataforma insular de Mallorca-Cabrera en el que se considera la topografía real y la influencia de diversos tipos de forzamiento. El tercer capítulo es la descripción, basada en datos experimentales prove nientes de una campaña oceanográfica realizada en 1991, de un nuevo estado de la circulación en la cuenca Este del Mar de Alborán. El siguiente artículo es el análisis dinámico de la estructura tridimensional de la circulación en el Mar de Alborán realizado a partir de los datos experi mentales obtenidos en una campaña oceanográfica llevada a cabo por la UIB y el Instituí de Ciéncies del Mar de Barcelona (CSIC) en 1992, bajo la dirección del Dr. -

Draft Scoping Report

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE IBHUBESI GAS PROJECT DRAFT SCOPING REPORT Prepared for: Department of Environmental Affairs On behalf of: Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd Prepared by: CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 APRIL 2014 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE IBHUBESI GAS PROJECT DRAFT SCOPING REPORT Prepared for: Department of Environmental Affairs Fedsure Forum Building, 2nd Floor North Tower 315 Pretorius Street PRETORIA, 0002 On behalf of: Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd 201 Two Oceans House, Surrey Place Surrey Road, Mouille Point Cape Town, 8005 Prepared by: CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd Contact person: Jonathan Crowther Unit 35 Roeland Square, Drury Lane CAPE TOWN, 8001 Tel: (021) 461 1118 / 9 Fax (021) 461 1120 E-mail: [email protected] SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 APRIL 2014 Sunbird Energy: Proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project PROJECT INFORMATION TITLE Draft Scoping Report for proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project APPLICANT Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANT CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd REPORT REFERENCE SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 DEA REFERENCE 14/12/16/3/3/2/587 REPORT DATE 25 April 2014 REPORT COMPILED BY: Jeremy Blood ......................................... Jeremy Blood (Pr.Sci.Nat.; CEAPSA) Associate REPORT REVIEWED BY: Jonathan Crowther .......................................... Jonathan Crowther (Pr.Sci.Nat.; CEAPSA) Managing Director CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd i Draft Scoping Report Sunbird Energy: Proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project EXPERTISE OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PRACTITIONER NAME Jonathan Crowther RESPONSIBILITY ON PROJECT Project leader and quality control DEGREE B.Sc. Hons (Geol.), M.Sc. (Env. Sci.) PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION Pr.Sci.Nat., CEAPSA EXPERIENCE IN YEARS 26 Jonathan Crowther has been an in environmental consultant since 1988 and is currently the Managing Director of CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd. -

STUDY GUIDE DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL Pressing Topics in the International Agenda

ABOUT THE JOURNAL UFRGS Model United Nations Journal is an academic vehicle, linked to UFRGSMUN, an sponsors Extension Project of the Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. It aims to contribute to the academic production in the fields of Inter- national Relations and International Law, as well as related areas, through the study of STUDY GUIDE DA UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL pressing topics in the international agenda. The DO RIO GRANDE DO SUL journal publishes original articles in English and Portuguese, about issues related to peace and security, environment, world economy, inter- national law, regional integration and defense. The journal’s target audience are undergradu- ate and graduate students. All of the contribu- tions to the journal are subject of careful scien- tific revision by postgraduate students. The journal seeks to promote the engagement in the debate of such important topics. STUDY GUIDE SOBRE O PERIÓDICO support O periódico acadêmico do UFRGS Modelo das Nações Unidas é vinculado ao UFRGSMUN, um frgs Projeto de Extensão da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul que possui como objetivo 2016 contribuir para a produção acadêmica nas áreas PPGEEI - UFRGS Núcleo Brasileiro de Estratégia e Relações Internacionais Programa de Pós-Graduação em de Relações Internacionais e Direito Internacio- Estudos Estratégicos Internacionais nal, bem como em áreas afins, através do estudo de temas pertinentes da agenda inter- nacional. O periódico publica artigos originais em inglês e português sobre questões relacio- nadas com paz e segurança, meio ambiente, frgs Instituto Sul-Americano de Política e Estratégia 2016 economia mundial, direito internacional, defesa Empowering people, e integração regional. -

Np 2 Africa Pilot Volume Ii

NP 2 RECORD OF AMENDMENTS The table below is to record Section IV Notice to Mariners amendments affecting this volume. Sub paragraph numbers in the margin of the body of the book are to assist the user with corrections to this volume from these amendments. Weekly Notices to Mariners (Section IV) 2005 2006 2007 2008 IMPORTANT − SEE RELATED ADMIRALTY PUBLICATIONS This is one of a series of publications produced by the United Kingdom Hydrographic Office which should be consulted by users of Admiralty Charts. The full list of such publications is as follows: Notices to Mariners (Annual, permanent, temporary and preliminary), Chart 5011 (Symbols and abbreviations), The Mariner’s Handbook (especially Chapters 1 and 2 for important information on the use of UKHO products, their accuracy and limitations), Sailing Directions (Pilots), List of Lights and Fog Signals, List of Radio Signals, Tide Tables and their digital equivalents. All charts and publications should be kept up to date with the latest amendments. NP 2 AFRICA PILOT VOLUME II Comprising the west coast of Africa from Bakasi Peninsula to Cape Agulhas; islands in the Bight of Biafra; Ascension Island; Saint Helena Island; Tristan da Cunha Group and Gough Island FOURTEENTH EDITION 2004 PUBLISHED BY THE UNITED KINGDOM HYDROGRAPHIC OFFICE E Crown Copyright 2004 To be obtained from Agents for the sale of Admiralty Charts and Publications Copyright for some of the material in this publication is owned by the authority named under the item and permission for its reproduction must be obtained from the owner. First published. 1868 Second edition. 1875 Third edition. -

Study of Heavy Metals Contamination in Mangrove Sediments of the Red Sea Coast of Yemen from Al-Salif to Bab-El-Mandeb Strait

Journal of Ecology & Natural Resources ISSN: 2578-4994 Study of Heavy Metals contamination in Mangrove Sediments of the Red Sea Coast of Yemen from Al-Salif to Bab-el-Mandeb Strait Al Hagibi HA*, Al-Selwi KM, Nagi HM and Al-Shwafi NA Research Article Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, Sana'a University, Yemen Volume 2 Issue 1 *Corresponding author: Hagib A Al-Hagibi, Department of Earth and Environmental Received Date: January 28, 2018 Sciences, Faculty of Science, Sana'a University, Yemen, Tel: 00967777322298; Email: Published Date: February 20, 2018 [email protected] DOI: 10.23880/jenr-16000121 Abstract This research aimed to estimate the concentration of Pb, Cd, Cr, Ni, Co, Cu, Zn, Mn, Mg and Fe in the sediments of mangrove habitats located in the Yemeni from Al-Salif to Bab-el-Mandeb Strait. Samples were collected seasonally at five locations: Al-Salif, Al-Urj, Al-Hodeidah, Yakhtol and Ghorairah, during the months of January, April, August and October 2013, which are chosen to represent the four seasons of a full year. Atomic Absorption Spectroscopy techniques were used to determine heavy metals concentration in the samples, which extracted using Acid digestion methods. The results showed that Heavy metals concentration (µg/g) in mangrove sediments were in the following order: Fe (8,432.0- 15,255.2) > Mg (915.2-2,066.0) > Mn (195.8-528.0) > Zn (27.5-57.2) > Cu (12.3-40.7) > Ni (15.5-34.7) > Cr (15.3-35.6) > Pb (6.2-16.6) > Co (6.2-15.8) > Cd (ND-0.57). -

Republic of South Africa

SAIHC8-5.3B REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA SAN HYDROGRAPHIC OFFICE NATIONAL REPORT TO THE 8TH SOUTHERN AFRICA AND ISLANDS HYDROGRAPHIC COMMISSION MEETING (SAIHC) 06 - 07 SEPTEMBER 2011 (WALVIS BAY, NAMIBIA) 2 CONTENTS 1. SA Navy Hydrographic Office (SANHO) Personnel 2. Hydrographic Surveys 3. Charts and Publications a. Charts International Charts National Paper Charts Vessel Traffic Service (VTS) & Traffic Separation Schemes (TSS) Small Craft Charts World Geodetic System (WGS 84) Print-on-Demand (PoD) Electronic Navigation Charts (ENCs) ENC Production ENC Production Priority Distribution Dissemination of ENC and related information b. Publications 4. Capacity Building Regional Capacity Building Initiatives Tide Gauge Installation Training 5. IHO Special Publication C-55 6. Oceanographic activities General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) IBCWIO Project (Int Bathymetric Chart of the West Indian Ocean) Tide Gauge Network 7. Appendix A – Status of Hydrographic Surveys along the RSA and Namibian Coastline 3 8thSAIHC MEETING REPORT BY THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA 1. SA Navy Hydrographic Office (SANHO) The SA Hydrographic Service is a government-funded service and is part of the SA Navy. The major assets for the Hydrographic Service is as follows: One Hecla Class Hydrographic Survey Vessel, namely SAS PROTEA. She carries on board two smaller survey launches that are deployed for shallow water surveys. There is an additional launch on a trailer and equipment that is used as a mobile survey unit. The Hydrographic Office, with the following principal functions: Conduct hydrographic surveys, produce paper nautical charts, electronic navigation charts (ENCs) and publications including List of Lights and Radio Signals, three volumes of Sailing Directions, maintaining a tide gauge network and provide tidal information, collect GEBCO data, issue Monthly Notices to Mariners, Radio Navigational Warnings and the provision of a Chart Depot service. -

PLACE and INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS INDEX Italicised Page Numbers Refer to Extended Entries

PLACE AND INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATIONS INDEX Italicised page numbers refer to extended entries Aaehen, 600, 611. 627 Adelaide (Australia), Aix-en-Provence, 554, Aleppo, 1260, 1263 Aalborg, 482, 491 100-1,114,117,124, 560 Aleppuzha (Aleppy). Aalsmeer,990 143,146 Aizwal. 718, 721. 748-9 739-40 Aalst, 193 Adehe Land. 100. 125. Ajaccio,554 Alessandria (Italy), 818 A.A. Neto Airport, 446 582 Ajman,131O Alesund, 1038 Aargau, 1251, 1253 Aden. 1603-6 Ajmer. 702, 755 Aleutians East (Ak.), Aarhus. 482, 490-1 Adilabad, 650 Akashi.834 1445 Aba,I031 Adiyaman, 1292, 1294 Akershus. 1037 Aleutians West (Ak.). Abaeo,l72 Adjaria. 437, 439 Akhali-Antoni.439 1445 Abadan. 781, 783 Ado-Ekiti, ID31 Akit.,834 Alexander Hamilton Abaing,854 Adola,533 Akjoujt,943 Airport. 1575 Abakan.412 AdonL 723 Akola, 702, 744-5 Alexandria (Egypt). Abancay,1085 Adrar (Algeria). 76 Akouta. 1029-30 512-15.517-18 Abariringa, 854 Adrar (Mauritania), 942 Akranes, 693 Alexandria (Romania), Abastuman, 438 Adventure, 666 Akron (Oh.), 1394, 1122 Abbotsford (Canada). Adygei, 401, 411 1523-5 Alexandria (Va.). 1395, 306 Adzope,453 Aksaray. 1292 1406,1551 Abdel Magid, 1140 Aegean Islands. 646 Aksaz Karaaga,. 1295 Alexandroupolis,643 Abeche, 346, 348 Aegean North Region, Aksu.426 Algarve, 1112-13 Abemama,854 642 Aktyubinsk.425-6 AIgeeiras. 1209 Abengourou,453 Aegean South Region, Akurc. 1032 Algeria, 8, 47, 59-60, Abeokuta, 1031 642 Akureyri, 693, 698 76-81 Aberdeen (Hong Kong), Aetolia and Acamania, Akwa Ibom, 1031 Algiers, 76-80 608 642 Akyab. 254, 257 AI-Hillah,788 Aberdeen (S.D.). 1540-1 Afam.945 Alabama.