A Suggested Blueprint for the Development of Maritime Archaeological Research in Namibia Bruno E.J.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memoirs of Hydrography

MEMOIRS 07 HYDROGRAPHY INCLUDING Brief Biographies of the Principal Officers who have Served in H.M. NAVAL SURVEYING SERVICE BETWEEN THE YEARS 1750 and 1885 COMPILED BY COMMANDER L. S. DAWSON, R.N. I 1s t tw o PARTS. P a r t II.—1830 t o 1885. EASTBOURNE: HENRY W. KEAY, THE “ IMPERIAL LIBRARY.” iI i / PREF A CE. N the compilation of Part II. of the Memoirs of Hydrography, the endeavour has been to give the services of the many excellent surveying I officers of the late Indian Navy, equal prominence with those of the Royal Navy. Except in the geographical abridgment, under the heading of “ Progress of Martne Surveys” attached to the Memoirs of the various Hydrographers, the personal services of officers still on the Active List, and employed in the surveying service of the Royal Navy, have not been alluded to ; thereby the lines of official etiquette will not have been over-stepped. L. S. D. January , 1885. CONTENTS OF PART II ♦ CHAPTER I. Beaufort, Progress 1829 to 1854, Fitzroy, Belcher, Graves, Raper, Blackwood, Barrai, Arlett, Frazer, Owen Stanley, J. L. Stokes, Sulivan, Berard, Collinson, Lloyd, Otter, Kellett, La Place, Schubert, Haines,' Nolloth, Brock, Spratt, C. G. Robinson, Sheringham, Williams, Becher, Bate, Church, Powell, E. J. Bedford, Elwon, Ethersey, Carless, G. A. Bedford, James Wood, Wolfe, Balleny, Wilkes, W. Allen, Maury, Miles, Mooney, R. B. Beechey, P. Shortland, Yule, Lord, Burdwood, Dayman, Drury, Barrow, Christopher, John Wood, Harding, Kortright, Johnson, Du Petit Thouars, Lawrance, Klint, W. Smyth, Dunsterville, Cox, F. W. L. Thomas, Biddlecombe, Gordon, Bird Allen, Curtis, Edye, F. -

Pyrenae 41-1 Pyrenae 04/06/10 10:33 Página 7

Pyrenae 41-1_Pyrenae 04/06/10 10:33 Página 7 PYRENAE, núm. 41, vol. 1 (2010) ISSN: 0079-8215 (p. 7-52) REVISTA DE PREHISTÒRIA I ANTIGUITAT DE LA MEDITERRÀNIA OCCIDENTAL JOURNAL OF WESTERN MEDITERRANEAN PREHISTORY AND ANTIQUITY Prehistoric Exploitation of Marine Resources in Southern Africa with Particular Reference to Shellfish Gathering: Opportunities and Continuities ANTONIETA JERARDINO Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies (ICREA)/UB-GEPEG Department of Prehistory, Ancient History and Archaeology Universitat de Barcelona C/ Montalegre, 6-8, E-08001 Barcelona [email protected] This paper discusses three case studies in which marine resources played an important role in human development in southern Africa over the last 164 ka: the ability of modern humans to exit successfully from Africa is seen partly as the result of a foraging expansion from rocky shores to sandy beaches; the location of an aggregation site close to the coast in the context of low human densities during post-glacial times allowed people to meet social needs and ensure population survival; and a heavy reliance on marine resources supported highest populations levels during the late Holocene. Broader and related issues are also discussed. KEYWORDS COASTAL ARCHAEOLOGY, OUT OF AFRICA, AGGREGATION SITE, PLEISTOCENE/ HOLOCENE TRAN- SITION, RESOURCE INTENSIFICATION, MEGAMIDDENS. Este artículo se centra en la discusión de tres casos de estudio en los cuales los recursos marinos desempeñaron un rol importante en el desarrollo humano del sur de África desde hace 164 ka. La capacidad de los humanos modernos de emigrar fuera de África se ve, en parte, como una expansión en la capacidad de forrajeo inicialmente expresada en el litoral rocoso para incluir más tarde las costas de playas de arena. -

Environmental Management Programme Report for the Development of the Kudu Gas Field on the Continental Shelf of Namibia

CSIR REPORT: CSIR/NRE/ECO/2005/0004/C ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE KUDU GAS FIELD ON THE CONTINENTAL SHELF OF NAMIBIA Prepared for: ENERGY AFRICA KUDU LIMITED Prepared by: P D Morant CSIR NATURAL RESOURCES AND ENVIRONMENT P O Box 320 Stellenbosch 7599 South Africa Tel: +27 21 888 2400 Fax: +27 21 888 2693 Keywords: Namibia Hydrocarbon production Coast Offshore Environmental management programme JUNE 2006 ENERGY AFRICA KUDU LIMITED ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME REPORT FOR THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE KUDU GAS FIELD ON THE CONTINENTAL SHELF OF NAMIBIA SCOPE The CSIR’s Natural Resources and Environment Unit was commissioned by Energy Africa Kudu Limited to provide an environmental management programme report (EMPR) for the development and operation of the Kudu gas field on the southern Namibian continental shelf. The EMPR is based on the environmental impact assessment (EIA) for the development of the Kudu gas field (CSIR Report ENV-S-C 2004-066, December 2004 plus Addendum, December 2005). The EMPR includes an updated description of the project reflecting the finally selected design and a re-assessment of the resulting environmental impacts. The EMPR includes: An overview of the project and various component activities which may have an impact on the environment; A qualitative assessment of the various project actions on the marine and coastal environment of southern Namibia; A management plan to guide the implementation of the mitigation measures identified in the EIA. The format of the EMPR is modelled on the South African Department of Minerals and Energy’s Guidelines for the preparation of Environmental Management Programme Reports for prospecting for and exploitation of oil and gas in the marine environment, Pretoria 1996. -

Southwest Coast of Africa

PUB. 123 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ SOUTHWEST COAST OF AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2012 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2012 THIRTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface 0.0 Pub. 123, Sailing Directions (Enroute) Southwest Coast of date of the publication shown above. Important information to Africa, Thirteenth Edition, 2012, is issued for use in conjunc- amend material in the publication is available as a Publication tion with Pub. 160, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) South Data Update (PDU) from the NGA Maritime Domain web site. Atlantic Ocean and Indian Ocean. The companion volume is Pubs. 124. 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website 0.0 Digital Nautical Chart 1 provides electronic chart coverage http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 18 August 2012, in- 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same cluding Notice to Mariners No. 33 of 2012. manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- Explanatory Remarks igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the designated course. Vessels following the directives must allow 0.0 Sailing Directions are published by the National Geospatial- for every influence tending to cause deviation from such track, Intelligence Agency (NGA), under the authority of Department and navigate so that the designated course is continuously be- of Defense Directive 5105.40, dated 12 December 1988, and ing made good. -

Coastways Tours and URI Adventures Joint Forces Offering This Trip Into the Namib Desert Between Luderitz and Walvis

We are proud to offer a unique 4x4 adventure trip through the worlds oldest desert, being one of only 7 remote wilderness areas left on our planet. We travel through the Namib between Luderitz and Walvis Bay formerly known as “Diamond Area no 2”. Places visited on the way include Silvia Hill, Meob Bay, Conception Bay & Sandwich Bay. Desert wildlife, spectacular scenery, untouched beaches, abandoned mining settlements, miles of sand driving and shipwrecks are some of the attractions along the way. Background: The discovery of diamonds in 1908 around Kolmanskuppe resulted in an uncontrollable diamond rush forcing the Government to establish the “Sperrgebiet” between 26-degree (Gibraltar) and the southern border stretching 100-kilometer inland. Prospectors were forced to turn northwards beyond the Sperrgebiet. This resulted in the discovery of diamonds at Spencer Bay in December 1908 and between Meob and the Conception Bay area (Diamond area no 2). This resulted in a total of 5000 diamond claims being registered in 1909 and hopeful prospectors tried their luck at Saddle Hill and Spencer Bay and via Swakopmund and Sandwich Harbour southwards towards Meob Bay. However, the small yields of diamonds from these claims resulted in only a few prospectors in the long term being successful. Transporting of supplies and mine equipment was effected mainly from Swakopmund by ship and the cutter Viking via Sandwich Harbour, Conception Bay and Meob Bay. Various shipping casualties occurred, such as when the Eduard Bohlen intend to off-load mining equipment, was consequently lost at Conception Bay (1909). In the area between Conception Bay and Meob Bay the mining settlements of Holsatia, Charlottenfelder and Grillenberger was established and no form of engine-driven transport was available during the first 15 years. -

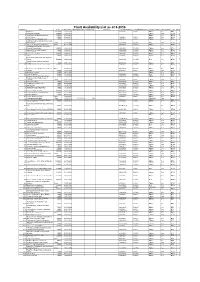

Chart Availability List As of 8-2016

Chart Availability List as of 8-2016 Number Title Scale Edition Date Withdrawn Date Replaced By Replaces Last NM Number Last NM Week-Year Product Status ARCS Chart Folio Disk 2 British Isles 1500000 23.07.2015 325\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF6 2 3 Chagos Archipelago 360000 21.06.2012 - Edition Yes BF38 5 5 `Abd Al Kuri to Suqutra (Socotra) 350000 07.03.2013 - Edition Yes BF32 5 6 Gulf of Aden 750000 26.04.2012 124\2015 1-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 7 Aden Harbour and Approaches 25000 31.10.2013 452\2016 3-2016 Edition Yes BF32 5 La Skhirra-Gabes and Ghannouch with 9 Approaches Plans 24.10.1986 1578\2014 14-2014 New Yes BF24 4 11 Jazireh-Ye Khark and Approaches Plans 03.12.2009 4769\2015 37-2015 Edition Yes BF40 5 Al Aqabah to Duba and Ports on the 12 Coast of Saudi Arabia 350000 14.04.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 13 Approaches to Cebu Harbour 35000 21.04.2011 3428\2014 31-2014 Edition Yes BF58 6 14 Cebu Harbour 12500 17.01.2013 4281P\2015 33-2015 Edition Yes BF58 6 15 Approaches to Jizan 200000 17.07.2014 105\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 16 Jizan 30000 19.05.2011 101\2015 53-2015 Edition Yes BF32 5 Plans of the Santa Cruz and Adjacent 17 Islands 500000 14.08.1992 2829\1995 33-1995 New Yes BF68 7 Falmouth Inner Harbour Including 18 Penryn 5000 20.02.2014 5087\2015 40-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 20 Ile d'Ouessant to Pointe de la Coubre 500000 22.08.2013 419\2016 2-2016 Edition Yes BF16 1 26 Harbours on the South Coast of Devon Plans 17.04.2014 5726\2015 45-2015 Edition Yes BF1 1 27 Bushehr 25000 15.07.2010 984\2016 7-2016 Edition Yes -

Partitioning of Nesting Space Among Seabirds of the Benguela Upwelling Region

PARTITIONING OF NESTING SPACE AMONG SEABIRDS OF THE BENGUELA UPWELLING REGION DAviD C. DuFFY & GRAEME D. LA CocK Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa, 7700. Received February /985 SUMMARY DuFFY, D. C. & LA CocK, G. D. 1985. Partitioning of nesting space among seabirds of the Benguela upwel ling region. Ostrich 56: 186-201. An examination of nesting habitats used by the four main species of seabirds nesting on southern African islands (Jackass Penguin Spheniscus demersus, Cape Cormorant Phalacrocorax capensis, Bank Cormorant P. neglectus and Cape Gannet Morus capensis) revealed relatively minor differences and extensive over laps between species, primarily in subcolony size, steepness of nesting substratum, and proximity to cliffs. A weak dominance hierarchy existed; gannets could displace penguins, and penguins could displace cor morants. This hierarchy appeared to have little effect on partitioning of nesting space. Species successfully defended occupied sites in most cases of interspecific conflict, suggesting that site tenure by one species could prevent nesting by another. The creation of additional nesting space on Namibian nesting platforms did not increase guano harvests, suggesting that nesting space had not previously limited the total nesting population of Cape Cormorants, the most abundant of the breeding species, in Namibia. While local shortages of nesting space may occur, populations of the four principal species of nesting seabirds in the Benguela upwelling region do not seem to have been limited by the availability of nesting space on islands. INTRODUCTION pean settlement, space for nesting was limited. Af ter settlement, human disturbance such as hunting The breeding seabirds of the Benguela upwel and guano extraction reduced nesting space, re ling region off Namibia and South Africa are be sulting in smaller populations of nesting seabirds. -

GIPE-004879.Pdf

... .. A STUD'lJN.COLONIAL GEOGRAPHY -· ··· ···-·· · . A . LBE ~.RT . DEMAN GEON :I l l ftO ,., 1110 1 ~ 0 111 1\ h O &0 .. , 6 0 9 0 lO> .120 l~ 5 150 16, 18 0 r '" "' I (. , •• "'• r4 ? 80 ! 0 (: f : ~ ~,-. 1:- A if t 1 I t , ,. r ' .v "- .. .. (\.., f r·•-- •• ~ ~_ I • ,, ...h ·;f" I "''I ... ~~) .I ·--.. ~ ,,.,..·'~· .. .. ..... .. ,,_ ··- ,"·. / •. .. , . ,. ...... t' ., I It ! ,... II 1 It "'~ol' r . ~ ·· ..~~ • , ,I ... I I , .: ··- :-.,. ... -·- (' I ,r· I ( "" THE BRITISH EMPIRE THROUGHOU T THE WORLD ON MY. III ' 1'111l':i I 'IW.I t: 1'1'IO N s,•• , •••• t, .lu!f- - ''"- ~ ...,.,._, )tlo),u NA.-,. 1 .c.J-'-"'"' .-A- ,. u.,.,. ··--L ,_ . l tt o 1n n 1:''11 1 OM 1111 THE BRITISH EMPIRE THE BRITISH EMPIRE A STUDY IN COLONIAL GEOGRAPHY BY ALBERT DEMANGEON PROFESSOR OF GEOGRAPHY AT THE SORBONNE TRANSLATED BY ERNEST F. ROW B.Sc. (Econ.) L.C.P. AtJTHOR OF "WORK WEALTH AND WAGES" "ELEMENTS OF ECONOMICS" ETC. TKANSLATOR OF GIDE'S "PRINCIPLES OF POLITICAL ECONOMY" GEORGE G. HARRAP & COMPANY LTD. LONDON CALCUTTA SYDNEY Fir61 Juoli6,ed 192.1 by GBORGB G. HARRAP &- Co. LTD. 39-11 P_arleer $Ired, Kingi'WaJI, Ltmtbm, W.C.• TRANSLATOR'S NOTE THE translator has endeavoured to provide an exact English version of Professor Demangeon's L' Empire britannique, which was published in 1923. No changes have been made in the text, except the turning of metric measures into their English equivalents and the occasional correction of an obvious slip or misprint. In the footnote references the number in black type following the author's name is the number of the book in the Bibliography at the end of this volume, where details as to title and publisher will be found. -

Forzamiento De Flujos Ageostróficos. Mar De

FORZAMIENTO DE FLUJOS AGEOSTRÓFICOS. MAR DE ALBORÁN Y PLATAFORMA DE MALLORCA-CABRERA Memoria para la obtención del título de doctor en Ciencias Físicas de: s Alvaro Viudez Lomba VOLUMEN I: TEXTO Universitat de les liles Balears Junio de 1994 Forzamiento de flujos ageostróficos. Mar de Alborán y plataforma de Mallorca-Cabrera. Memoria para la obtención del título de Doctor en Ciencias Físicas de: Alvaro Viudez Lomba Director: Dr. Joaquín Tintoré Subirana VOLUMEN I: TEXTO Universitat de les Ules Balears Junio de 1994 A mis padres, por su generosidad. Prólogo El contenido básico de la presente memoria de tesis doctoral, dirigida por el Dr. Joaquín Tintoré, está formado por un conjunto de artículos de Oceano grafía Física elaborados desde 1991 en colaboración con otros investigadores. El primer capítulo sitúa e introduce, desde la perspectiva general de la Oceanografía Física, los diversos trabajos que forman esta tesis. El segundo capítulo, cuyo principal autor es el Dr. Francisco E. Werner, es básicamente un estudio numérico de la circulación en la plataforma insular de Mallorca-Cabrera en el que se considera la topografía real y la influencia de diversos tipos de forzamiento. El tercer capítulo es la descripción, basada en datos experimentales prove nientes de una campaña oceanográfica realizada en 1991, de un nuevo estado de la circulación en la cuenca Este del Mar de Alborán. El siguiente artículo es el análisis dinámico de la estructura tridimensional de la circulación en el Mar de Alborán realizado a partir de los datos experi mentales obtenidos en una campaña oceanográfica llevada a cabo por la UIB y el Instituí de Ciéncies del Mar de Barcelona (CSIC) en 1992, bajo la dirección del Dr. -

Day Tours & Experiences NAMIBIA

Day Tours & Experiences NAMIBIA Our selection of day tours and experiences encompass a wide selection of full day and half day excursions from areas around Namibia. These excursions allow guests to fully customise their tour to suit their individual interests. We recognise our guests seek real experiences and a depth of understanding that expands their full appreciation of their chosen destination. HORSE RIDING SAFARIS The horse-back riding offered can be tailored to suit each guests’ riding ability. There are sunrise and sunset options, each of which lasts three to four hours. End the experience with refreshing drinks and delicious snacks. The horses range from gentle souls to more lively rides, once again dependant on each client’s level of experience. For the SOSSUSVLEI HOT AIR BALLOONING more adventurous of spirit, a night under the stars with softly As the sun’s first rays peek over scarlet sand dunes, the hot burring horses should be on everyone’s bucket list. air balloon drifts slowly upward, revealing the undulating landscapes of Sossusvlei. The adventure begins before sunrise when you are collected from your accommodation, and driven to the take-off area. Once the balloon is airborne you drift silently over the desert for about an hour, where the views of the Namib Desert are exceptional. SOSSUSVLEI SAND DUNE EXCURSIONS Enter the Namib-Naukluft Park at sunrise, while the temperature is mild and the dune contrasts are at their best. Travel in one of the all-terrain URI game viewer vehicles, custom-built in Namibia with your own specially-trained guide who will share all his knowledge of the area, animals and plant life. -

Spatiotemporal Shoreline Dynamics of Namibian Coastal Lagoons Derived by a Dense Remote Sensing Time Series Approach

Originally published as: Behling, R., Milewski, R., Chabrillat, S. (2018): Spatiotemporal shoreline dynamics of Namibian coastal lagoons derived by a dense remote sensing time series approach. - International Journal of Applied Earth Observation and Geoinformation, 68, pp. 262—271. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jag.2018.01.009 1 Spatiotemporal shoreline dynamics of Namibian coastal lagoons 2 derived by a dense remote sensing time series approach 3 Robert Behling*, Robert Milewski, Sabine Chabrillat 4 Remote Sensing Section - GFZ German Research Centre for Geosciences, Telegrafenberg, 14473 Potsdam, 5 Germany 6 * Corresponding author 7 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 8 ABSTRACT 9 This paper proposes the remote sensing time series approach WLMO (Water-Land MOnitor) to monitor 10 spatiotemporal shoreline changes. The approach uses a hierarchical classification system based on 11 temporal MNDWI-trajectories with the goal to accommodate typical uncertainties in remote sensing 12 shoreline extraction techniques such as existence of clouds and geometric mismatches between images. 13 Applied to a dense Landsat time series between 1984 and 2014 for the two Namibian coastal lagoons at 14 Walvis Bay and Sandwich Harbour the WLMO was able to identify detailed accretion and erosion 15 progressions at the sand spits forming these lagoons. For both lagoons a northward expansion of the sand 16 spits of up to 1000m was identified, which corresponds well with the prevailing northwards directed ocean 17 current and wind processes that are responsible for the material transport along the shore. At Walvis Bay 18 we could also show that in the 30 years of analysis the sand spit’s width has decreased by more than a half 19 from 750m in 1984 to 360m in 2014. -

Draft Scoping Report

PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE IBHUBESI GAS PROJECT DRAFT SCOPING REPORT Prepared for: Department of Environmental Affairs On behalf of: Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd Prepared by: CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 APRIL 2014 PROPOSED DEVELOPMENT OF THE IBHUBESI GAS PROJECT DRAFT SCOPING REPORT Prepared for: Department of Environmental Affairs Fedsure Forum Building, 2nd Floor North Tower 315 Pretorius Street PRETORIA, 0002 On behalf of: Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd 201 Two Oceans House, Surrey Place Surrey Road, Mouille Point Cape Town, 8005 Prepared by: CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd Contact person: Jonathan Crowther Unit 35 Roeland Square, Drury Lane CAPE TOWN, 8001 Tel: (021) 461 1118 / 9 Fax (021) 461 1120 E-mail: [email protected] SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 APRIL 2014 Sunbird Energy: Proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project PROJECT INFORMATION TITLE Draft Scoping Report for proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project APPLICANT Sunbird Energy (Ibhubesi) Pty Ltd ENVIRONMENTAL CONSULTANT CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd REPORT REFERENCE SE01IPP/DSR/Rev.0 DEA REFERENCE 14/12/16/3/3/2/587 REPORT DATE 25 April 2014 REPORT COMPILED BY: Jeremy Blood ......................................... Jeremy Blood (Pr.Sci.Nat.; CEAPSA) Associate REPORT REVIEWED BY: Jonathan Crowther .......................................... Jonathan Crowther (Pr.Sci.Nat.; CEAPSA) Managing Director CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd i Draft Scoping Report Sunbird Energy: Proposed development of the Ibhubesi Gas Project EXPERTISE OF ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT PRACTITIONER NAME Jonathan Crowther RESPONSIBILITY ON PROJECT Project leader and quality control DEGREE B.Sc. Hons (Geol.), M.Sc. (Env. Sci.) PROFESSIONAL REGISTRATION Pr.Sci.Nat., CEAPSA EXPERIENCE IN YEARS 26 Jonathan Crowther has been an in environmental consultant since 1988 and is currently the Managing Director of CCA Environmental (Pty) Ltd.