Print This Article

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bhakti in New Normal Era

Bhakti In New Normal Era L. Eka M. Julianingsih P STAH N Mpu Kuturan Singaraja A. Introduction The year of 2020 begin with unexpected pandemic which become big disaster for almost every country including Indonesia. This pandemic known as the COVID-19. It is not only paralyzed the world of health sector but affected the education sector also. With this condition the government continues to impose policies, starting from the central level to the regions, not least in the state of Bali. The policies carried out by the state government of Bali which restrict to people for there activity, as everybody must follow social distancing and this are felt different by Balinese community. Bali actually famous for its religion and culture, which is full of ritual ceremonies in their daily lives, Balinese Hindu society performs rituals every day from the smallest level up to large ceremonies which of course often involve many people, both in terms of the ceremonies of Dewa Yadnya, Manusa Yadnya, Rsi Yadnya, Bhuta Yadnya and Pitra Yadnya. The yadnya ceremony that is seen and often performed on a daily basis by Hindus is an implementation of the teachings of Bhoutika bhakti, namely bhakti which is done by making various kinds of offerings or visiting holy places. Especially during pujawali/odalan, Hindus will flock to visit the temple with relatives, as a form of devotion and love to God for omnipotence. L. Eka M. Julianingsih P | 316 With the COVID-19, the Hindus is invited back to perform rituals that are simple but do not reduce the meaning of all the processions that occur in the implementation. -

Penjor in Hindu Communities

Penjor in Hindu Communities: A symbolic phrases of relations between human to human, to environment, and to God Makna penjor bagi Masyarakat Hindu: Kompleksitas ungkapan simbolis manusia kepada sesama, lingkungan, dan Tuhan I Gst. Pt. Bagus Suka Arjawa1* & I Gst. Agung Mas Rwa Jayantiari2 1Department of Sociology, Faculty of Social and Political Sciences, Universitas Udayana 2Faculty of Law, Universitas Udayana Address: Jalan Raya Kampus Unud Jimbaran, South Kuta, Badung, Bali 80361 E-mail: [email protected]* & [email protected] Abstract The purpose of this article was to observe the development of the social meaning derived from penjor (bamboo decorated with flowers as an expression of thanks to God) for the Balinese Hindus. In the beginning, the meaning of penjor serves as a symbol of Mount Agung, and it developed as a human wisdom symbol. This research was conducted in Badung and Tabanan Regency, Bali using a qualitative method. The time scope of this research was not only on the Galungan and Kuningan holy days, where the penjor most commonly used in society. It also used on the other holy days, including when people hold the caru (offerings to the holy sacrifice) ceremony, in the temple, or any other ceremonial place and it is also displayed at competition events. The methods used were hermeneutics and verstehen. These methods served as a tool for the researcher to use to interpret both the phenomena and sentences involved. The results of this research show that the penjor has various meanings. It does not only serve as a symbol of Mount Agung and human wisdom; and it also symbolizes gratefulness because of God’s generosity and human happiness and cheerfulness. -

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali

Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Fine Arts of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Jennifer L. Goodlander August 2010 © 2010 Jennifer L. Goodlander. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali by JENNIFER L. GOODLANDER has been approved for the Interdisciplinary Arts and the College of Fine Arts by William F. Condee Professor of Theater Charles A. McWeeny Dean, College of Fine Arts 3 ABSTRACT GOODLANDER, JENNIFER L., Ph.D., August 2010, Interdisciplinary Arts Body of Tradition: Becoming a Woman Dalang in Bali (248 pp.) Director of Dissertation: William F. Condee The role of women in Bali must be understood in relationship to tradition, because “tradition” is an important concept for analyzing Balinese culture, social hierarchy, religious expression, and politics. Wayang kulit, or shadow puppetry, is considered an important Balinese tradition because it connects a mythic past to a political present through public, and often religiously significant ritual performance. The dalang, or puppeteer, is the central figure in this performance genre and is revered in Balinese society as a teacher and priest. Until recently, the dalang has always been male, but now women are studying and performing as dalangs. In order to determine what women in these “non-traditional” roles means for gender hierarchy and the status of these arts as “traditional,” I argue that “tradition” must be understood in relation to three different, yet overlapping, fields: the construction of Bali as a “traditional” society, the role of women in Bali as being governed by “tradition,” and the performing arts as both “traditional” and as a conduit for “tradition.” This dissertation is divided into three sections, beginning in chapters two and three, with a general focus on the “tradition” of wayang kulit through an analysis of the objects and practices of performance. -

Identifikasi Kolektif Dan Ideologisasi Jihad: Studi Kualitatif Teroris Di Indonesia

TOPIK IDENTIFIKASI KOLEKTIF DAN IDEOLOGISASI JIHAD: STUDI KUALITATIF TERORIS DI INDONESIA G A Z I S A L O O M*) ABSTRAK Artikel ini menggambarkan bahwa para teroris setidaknya di Indonesia adalah kumpulan orang normal yang memiliki pikiran yang sehat dan memiliki tujuan jangka panjang untuk menegakkan sistem pemerintahan Islam yang berdasarkan ajaran Al-Qur’an dan Hadis. Penelitian ini menggunakan pendekatan kualitatif dengan pengumpulan data yang dilakukan melalui wawancara, telaah dokumen, dan informasi media tentang teroris dan terorisme. Satu orang mantan teroris yang pernah terlibat dalam kasus Bom Bali 1 dipilih untuk menjadi responden penelitian. Data yang diperoleh dari hasil wawancara mendalam dan telaah dokumen dianalisa dengan teori identitas sosial dan teori kognisi sosial mengenai ideologisasi jihad. Artikel ini menyimpulkan bahwa proses perubahan orang biasa menjadi teroris sangat berkaitan dengan ideologisasi jihad dan pencarian identitas. KATA KUNCI: Psikopat, Gangguan Mental, Normal, Islam ABSTRACT This article articulates that the terrorists in Indonesia are basically a group of normal people who have sound minds and a long-term goal to establish an Islamic government system based on the teachings of the Quran and Hadith. This study employed qualitative approach by acquiring the data through interviews, document analysis and media information covering terrorists and terrorism. A former terrorist involved in Bali bombing I served as the research informant. Data from in-depth interviews and document analysis were analyzed by utilizing social identity and social cognition theory about ideology of jihad. The article concludes that the changing process from the ordinary people into the terrorist strongly relates to jihad ideology and search for identity. -

Bharata Natyam Is a Traditional Female Solo Dance Form in Tamil Nadu, Southeast India

=Wor d of Dance< Asian Dance SECOND EDITION WoD-Asian dummy.indd 1 12/11/09 3:16:42 PM World of Dance African Dance, Second Edition Asian Dance, Second Edition Ballet, Second Edition European Dance: Ireland, Poland, Spain, and Greece, Second Edition Latin and Caribbean Dance Middle Eastern Dance, Second Edition Modern Dance, Second Edition Popular Dance: From Ballroom to Hip-Hop WoD-Asian dummy.indd 2 12/11/09 3:16:43 PM =Wor d of Dance< Asian Dance SECOND EDITION Janet W. Descutner Consulting editor: Elizabeth A. Hanley, Associate Professor Emerita of Kinesiology, Penn State University Foreword by Jacques D’Amboise, Founder of the National Dance Institute WoD-Asian dummy.indd 3 12/11/09 3:16:44 PM World of Dance: Asian Dance, Second Edition Copyright © 2010 by Infobase Publishing All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher. For information, contact: Chelsea House An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Descutner, Janet. Asian dance / by Janet W. Descutner. — 2nd ed. p. cm. — (World of dance) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-60413-478-0 (hardcover) ISBN 978-1-4381-3078-1 (e-book) 1. Dance—Asia. I. Title. II. Series. GV1689.D47 2010 793.3195—dc22 2009019582 Chelsea House books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. -

Bangli Explore 2021

BANGLI EXPLORE 2021 Bangli Explore 2020 I Gede Sutarya Pariwisata Agama, Budaya dan Spiritual e-ISSN 2684-964X i I Gede Sutarya Bangli Explore 2021 Mempromosikan budaya, agama dan spiritual Kabupaten Bangli, sebagai destinasi pariwisata Persembahan untuk Bangli Yayasan Wikarman 2021 ii Bangli Explore 2021 Sutarya, I Gede Lay out: I Nyoman Jati Karmawan Sutarya, I Gede Bangli Explore Layout: I Nyoman Jati Karmawan Yayasan Wikarman Bangli 2020 VI+39 Halaman; e-ISSN 2684-964X 1. Pariwisata 3. Kebudayaan 2. Agama 4. Spiritual Penerbit Yayasan Wikarman Toko Ditu, Jalan Tirta Geduh, LC Subak Aya, Bangli, Bali 80613 Telp (Hp) +6281997852219 Email: [email protected] Percetakan: Bhakti Printing, Jl Singasari Utara, Gang Umapunggul, Denpasar Hak Cipta Dilindungi Undang-Undang iii Kata Pengantar Om Swastyastu, Puja bhakti, kami panjatkan kepada Ida Sanghyang Widhi, karena Bangli Explore 2021 bisa terbit. Bangli Explore 2021 ini merupakan lanjutan dari Bangli Explore 2020 dan 2019. Karena itu, pada tahun ini, Bangli Explore telah terbit tiga kali. Hal ini merupakan kebanggaan bagi kami, yang ingin terus berkiprah dan berkontribusi dalam pembangunan Bangli, melalui promosi pariwisata. Kami mengucapkan terima kasih kepada Saudara I Gede Sutarya, yang telah menulis Bangli Explore 2021 ini. Kami juga berterima kasih kepada berbagai pihak yang telah membantu melengkapi data- data dalam buku ini, seperti Bapak I Ketut Kayana, yang merupakan Bendesa Majelis Desa Adat Kabupaten Bangli. Terima kasih juga untuk Bapak I Nyoman Sukra, yang merupakan Ketua Parisada Hindu Dharma Indonesia (PHDI) Kabupaten Bangli atas berbagai masukannya. Kami juga mengucapkan terima kasih kepada Bupati Bangli, I Made Gianyar, yang juga telah memberikan berbagai fasilitas untuk melengkapi data-data buku ini. -

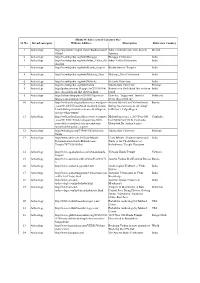

3.Hindu Websites Sorted Country Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Country wise Sl. Reference Country Broad catergory Website Address Description No. 1 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindushahi Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 2 Afghanistan Dynasty http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jayapala King Jayapala -Hindu Shahi Dynasty Afghanistan, Pakistan 3 Afghanistan Dynasty http://www.afghanhindu.com/history.asp The Hindu Shahi Dynasty (870 C.E. - 1015 C.E.) 4 Afghanistan History http://hindutemples- Hindu Roots of Afghanistan whthappendtothem.blogspot.com/ (Gandhar pradesh) 5 Afghanistan History http://www.hindunet.org/hindu_history/mode Hindu Kush rn/hindu_kush.html 6 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindu.wordpress.com/ Afghan Hindus 7 Afghanistan Information http://afghanhindusandsikhs.yuku.com/ Hindus of Afaganistan 8 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.com/vedic.asp Afghanistan and It's Vedic Culture 9 Afghanistan Information http://www.afghanhindu.de.vu/ Hindus of Afaganistan 10 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.afghanhindu.info/ Afghan Hindus 11 Afghanistan Organisation http://www.asamai.com/ Afghan Hindu Asociation 12 Afghanistan Temple http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hindu_Temples_ Hindu Temples of Kabul of_Kabul 13 Afghanistan Temples Database http://www.athithy.com/index.php?module=p Hindu Temples of Afaganistan luspoints&id=851&action=pluspoint&title=H indu%20Temples%20in%20Afghanistan%20. html 14 Argentina Ayurveda http://www.augurhostel.com/ Augur Hostel Yoga & Ayurveda 15 Argentina Festival http://www.indembarg.org.ar/en/ Festival of -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id10. India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civil Indus Valley Civilisation India ization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at newly Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html discovered site 9 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia om/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village in found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress.c Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia om/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200-year- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia-unearthed- Unearthed By Archaeologists 11 Archaelogy http://wikimapia.org/7359843/Takshashila- Takshashila University Pakistan Taxila 12 Archaelogy http://www.agamahindu.com/vietnam-hindu- Vietnam -

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts

Society for Ethnomusicology Abstracts Musicianship in Exile: Afghan Refugee Musicians in Finland Facets of the Film Score: Synergy, Psyche, and Studio Lari Aaltonen, University of Tampere Jessica Abbazio, University of Maryland, College Park My presentation deals with the professional Afghan refugee musicians in The study of film music is an emerging area of research in ethnomusicology. Finland. As a displaced music culture, the music of these refugees Seminal publications by Gorbman (1987) and others present the Hollywood immediately raises questions of diaspora and the changes of cultural and film score as narrator, the primary conveyance of the message in the filmic professional identity. I argue that the concepts of displacement and forced image. The synergistic relationship between film and image communicates a migration could function as a key to understanding musicianship on a wider meaning to the viewer that is unintelligible when one element is taken scale. Adelaida Reyes (1999) discusses similar ideas in her book Songs of the without the other. This panel seeks to enrich ethnomusicology by broadening Caged, Songs of the Free. Music and the Vietnamese Refugee Experience. By perspectives on film music in an exploration of films of four diverse types. interacting and conducting interviews with Afghan musicians in Finland, I Existing on a continuum of concrete to abstract, these papers evaluate the have been researching the change of the lives of these music professionals. communicative role of music in relation to filmic image. The first paper The change takes place in a musical environment which is if not hostile, at presents iconic Hollywood Western films from the studio era, assessing the least unresponsive towards their music culture. -

Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals RT1806 C00.Qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page Ii

RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page i encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page ii ROUTLEDGE ENCYCLOPEDIAS OF RELIGION AND SOCIETY David Levinson, Series Editor The Encyclopedia of Millennialism and Millennial Movements Richard A. Landes, Editor The Encyclopedia of African and African-American Religions Stephen D. Glazier, Editor The Encyclopedia of Fundamentalism Brenda E. Brasher, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religious Freedom Catharine Cookson, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religion and War Gabriel Palmer-Fernandez, Editor The Encyclopedia of Religious Rites, Rituals, and Festivals Frank A. Salamone, Editor RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page iii encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals Frank A. Salamone, Editor Religion & Society A Berkshire Reference Work ROUTLEDGE New York London RT1806_C00.qxd 4/23/2004 2:13 PM Page iv Published in 2004 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.uk.co A Berkshire Reference Work. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group. Copyright © 2004 by Berkshire Publishing Group Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Encyclopedia of religious rites, rituals, and festivals / Frank A. -

Cudamani 'Odalan Bali: an Offering of Music and D

Cudamani ‘Odalan Bali: An Offering of Music and Dance’ 1st April 2005 San Francisco, Zellerbach Hall by Renee Renouf Cudamani refers to the third eye of Shiva, not only destroying but also annihilating ignorance. This program came with impressive credentials not noted prior to sitting down. An informative 45 minute-talk prior to the © Jorge Vismara curtain, made me realize the varied 'Odalan Bali' reviews genesis of this unusual program. recent Cudamani reviews In the 1970's, Judy Mitoma, a young more Renee Renouf reviews Discuss this review Japanese-American woman, was (Open for at least 6 months) studying Indonesian dance at UCLA at the high tide of the Ethno- musicology program and the Dance Department. She met Hardja Susilo and the two married. Their daughter Emiko Saraswati Susilo attended U.C., Berkeley’s Music Department, studying Balanese gamelan, performing with the nearby Gamelan Sekar Jaya. Emiko met and married I Dewa Putu Barata, going to live in Pengosekan, Barata’s native village in Bali.. Mitoma became a professor and chair of UCLA’s Dance Department; she was a key in the transformation to the current World Cultures Department. She also was one of the instrumental figures in the 1990 Los Angeles Asian Festival and now directs the UCLA Center for Intercultural Performance. With Bali undergoing the transition pressures from an agricultural society, into the nine-to-five world, cell phones, television and set pieces for the tourist industry, Cudamani was created in 1997 in an effort to retain the ritual roots of Balinese tradition in the training of young artists.The founding directors were I Dewa Putu Berata, his brother Dewa Ketut Ali and I Nyoman Cerita. -

2.Hindu Websites Sorted Category Wise

Hindu Websites sorted Category wise Sl. No. Broad catergory Website Address Description Reference Country 1 Archaelogy http://aryaculture.tripod.com/vedicdharma/id1 India's Cultural Link with Ancient Mexico 0.html America 2 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harappa Harappa Civilisation India 3 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indus_Valley_Civ Indus Valley Civilisation India ilization 4 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kiradu_temples Kiradu Barmer Temples India 5 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mohenjo_Daro Mohenjo_Daro Civilisation India 6 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nalanda Nalanda University India 7 Archaelogy http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Taxila Takshashila University Pakistan 8 Archaelogy http://padmasrinivas.blogspot.in/2007/05/bhi Bhima's son Gadotkach like skeleton India mas-son-gadotkach-like-skeleton.html found 9 Archaelogy http://selians.blogspot.in/2010/01/ganesha- Ganesha, ‘lingga yoni’ found at Indonesia lingga-yoni-found-at-newly.html newly discovered site 10 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress Ancient Idol of Lord Vishnu found Russia .com/2012/05/27/ancient-idol-of-lord-vishnu- during excavation in an old village found-during-excavation-in-an-old-village-in- in Russia’s Volga Region russias-volga-region/ 11 Archaelogy http://vedicarcheologicaldiscoveries.wordpress Mahendraparvata, 1,200-Year-Old Cambodia .com/2013/06/15/mahendraparvata-1200- Lost Medieval City In Cambodia, year-old-lost-medieval-city-in-cambodia- Unearthed By Archaeologists unearthed-by-archaeologists/