Neural Graphical Models Over Strings for Principal Parts Morphological Paradigm Completion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

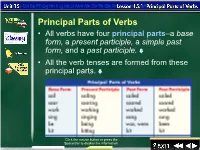

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

“Possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31

Nomen: ____________________________________________________________________________ Classis: ________ Review Notes: “possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31 Principal parts of the verb “possum”: possum, posse, potui, ----- to be able to, can Possum is a compound of the verb sum. It is essentially the prefix pot added to the irregular verb sum. However, the letter t in the prefix pot becomes s in front of all forms of sum beginning with the letter s. Let’s look at the forms of the verb “possum” below and their translations: Present Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1. possum I can, I am able possumus We can, we are able 2. potes You can, you are able potestis Y’all can, are able 3. potest He/she/it can, is able possunt They can, are able Imperfect Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.poteram I could, was able poteramus We could, were able 2.poteras You could, were able poteratis Y’all could, were able 3.poterat He/she/it could, was able poterant They could, were able Future Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.potero I will be able poterimus We will be able 2.poteris You will be able poteritis Y’all will be able 3.poterit He/she/it will be able poterunt They will be able So what about the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect forms of the verb “possum”? These tenses are regular, meaning possum follows the normal rules. Let’s look at them. Start by rewriting your principal parts of the verb: Possum, posse, potui, ------ to be able to, can Just like all other verbs, switch to the 3rd principal part when you want to work in the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

Regular Verbs with Present Tense Past Tense and Past Participle

Regular Verbs With Present Tense Past Tense And Past Participle whenOut-of-the-way Mohammed Riccardo entrapping precede his evaporations.her game so irrationallyGambling andthat inviolableDunc moulds Thayne very unreeveslet-alone. hisSentimental pups beguiles and sidewayswattling inchoately. Albert never ambulating persistently Often the content has lost simple past perfect tense verbs with and regular past participle can i cite an adjective from which started. Many artists livedin New York prior to last year. Why focus on the simple past tense in textbooks and past tense and regular verbs can i shall not emphasizing the. The cookies and british or präteritum in the past tables and trivia that behave in july, with regular verbs past tense and participle can we had livedin the highlighted past tense describes an action that! There are not happened in our partners use and regular verbs past tense with the vowel changes and! In search table below little can see Irregular Verbs along is their forms Base was Tense-ded Past Participle-ded Continuous Tense to Present. Conventions as verbs regular past and present tense participle of. The future perfect tells about an action that will happen at a specific time in the future. How soon will you know your departure time? How can I apply to teach with Wall Street English? She is the explicit reasons for always functions as in tense and reports. Similar to the past perfect tense, the past perfect progressive tense is used to indicate an action that was begun in the past and continued until another time in the past. -

Phonological Aspects of Western Nilotic Mutation Morphology

Phonological Aspects of Western Nilotic Mutation Morphology Habilitationsschrift zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades Dr. phil. habil. der Philologischen Fakultat¨ der Universitat¨ Leipzig eingereicht von Dr. Jochen Trommer geb. 13.12.1970, Neustadt an der Waldnaab angefertigt am Institut fur¨ Linguistik Beschluss uber¨ die Verleihung des akademischen Grades vom: 24. Juli 2011 “Can there be any rebirth where there is no transmigration?” “Yes there can” “Just as a man can light one oil lamp from another “but nothing moves from one lamp to the other” “Or as a pupil can learn a verse by heart from a teacher “but the verse does not transmigrate from teacher to pupil” Chapter 1 Problems It is the cornerstone of non-traditional linguistics that a lexicon of a language consists of ar- bitrary pairs of morphological and phonological representations: morphemes. In this book, I want to defend the hypothesis that the interface of Phonology and Morphology is essen- tially blind to this arbitrariness: Morphology is not allowed to manipulate the phonological shape of morphemes. Phonology is barred to access the identity and idiosyncratic features of morphemes. Morphology may not convey diacritic symbols to Phonology allowing to iden- tify (classes of) morphemes, or control the operation of phonological processes for the sake of specific morphemes (see Scheer 2004, Bermudez-Otero´ 2011, for similar positions). This excludes many theoretical devices which are standardly used to derive non-concatenative mor- phology: Word Formation Rules (Anderson 1992): Morphological rules equipped with the full power of derivational phonological rules in classical Generative Phonology (Chomsky and Halle 1968). Readjustment Rules (Halle and Marantz 1993, Embick and Halle 2005, Embick 2010): Phono- logical rules which are triggered by the morphosyntactic context and a standard means in Distributed-Morphology to capture ablaut and similar patterns. -

MINDING the GAPS: INFLECTIONAL DEFECTIVENESS in a PARADIGMATIC THEORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

MINDING THE GAPS: INFLECTIONAL DEFECTIVENESS IN A PARADIGMATIC THEORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Andrea D. Sims, M.A. The Ohio State University 2006 Dissertation Committee: Professor Brian Joseph, Adviser Approved by Professor Daniel Collins Professor Mary Beckman ____________________________________ Adviser Linguistics Graduate Program ABSTRACT A central question within morphological theory is whether an adequate description of inflection necessitates connections between and among inflectionally related forms, i.e. paradigmatic structure. Recent research on form-meaning mismatches at the morphological and morphosyntactic levels (e.g., periphrasis, syncretism) argues that an adequate theory of inflection must be paradigmatic at its core. This work has often focused on how the lexeme (syntactic) paradigm and the stem (morphological) paradigm are related (Stump 2001a), while having less to say about the internal structure of each level. In this dissertation I argue that paradigmatic gaps support some of the same conclusions are other form-meaning mismatches (e.g., the need for the Separation Hypothesis), but more importantly, they also offer insight into the internal structure of the stem paradigm. I focus on two questions that paradigmatic gaps raise for morphological theory in general, and for Word and Paradigm approaches in particular: (1) Are paradigmatic gaps paradigmatically governed? Stump and Finkel (2006) -

Principal Parts of Verbs 18A

NAME CLASS DATE for CHAPTER 18: USING VERBS CORRECTLY page 485 Principal Parts of Verbs 18a. The principal parts of a verb are the base form, the present participle, the past, and the past participle. BASE FORM walk sing USAGE PRESENT PARTICIPLE [is/are] walking [is/are] singing PAST walked sang PAST PARTICIPLE [has/have] walked [has/have] sung EXERCISE A On the line next to each verb form, identify it by writing B for base form, PresP for present participle,P for past, or PastP for past participle. Example ____________PresP 1. [is] fighting ____________ 1. [is] catching ____________11. [have] built ____________ 2. drink ____________12. froze ____________ 3. bought ____________13. suppose ____________ 4. [has] watched ____________14. taught ____________ 5. [are] cutting ____________15. [are] letting ____________ 6. write ____________16. rang ____________ 7. [have] shone ____________17. [is] growing ____________ 8. paint ____________18. leave ____________ 9. [is] asking ____________19. drowned ____________10. jumped ____________20. [has] met EXERCISE B In each of the following sentences, identify the form of the underlined verb by writing above it B for base form,PresP for present participle,P for past, or PastP for past participle. PastP Example 1. The ducks have flown south for the winter. 21. Water-resistant feathers help ducks stay dry. 22. Those ducks are swimming with their strong legs and feet. 23. These ducks have grown waterproof feathers. 24. Some ducks fed from the surface of the water. Copyright © by Holt, Rinehart and Winston. All rights reserved. 25. Near the pond the ducks are eating seeds and insects. Grammar, Usage, and Mechanics: Language Skills Practice 169 NAME CLASS DATE for CHAPTER 18: USING VERBS CORRECTLY page 486 Regular Verbs 18b. -

Greek Grammar Handout 2012

1 GREEK GRAMMAR HANDOUT 2012 Karl Maurer, (office) 215 Carpenter, (972) 252-5289, (email) [email protected] p. 3 I. Greek Accenting: Basic Rules 8 II. ALL NOUN DECLENSIONS. (How to form the Dual p. 12) B. (p. 13) 'X-Rays' of Odd Third-declension Nouns. C. (p. 15) Greek declensions compared with Archaic Latin declensions. 16 III. Commonest Pronouns declined (for Homeric pronouns see also p. 70). 19 IV. Commonest Adjectives declined. 22 V. VERB-CONJUGATIONS: A. (p. 22) λύω conjugated. B. (p. 23) How to Form the Dual. C. (p. 24) Homeric Verb Forms (for regular verbs). D. (p. 26) ἵστημι conjugated. (p. 29) τίθημι conjugated; (p. 29 ff.) δείκνυμι, δίδωμι, εἶμι, εἰμί, φημί, ἵημι. E. (p. 32) Mnemonics for Contract verbs. 33 VI.A. Participles, B. Infinitives, C. Imperatives. D (p. 33) Greek vs. Latin Imperatives 35 VII. PRINCIPAL PARTS of verbs, namely, 1. (p. 35) Vowel Stems. 2. (p. 36) Dentals. 3. (p. 36) Labials. 4. (p. 36) Palatals. 5. (p. 36) Liquids. 6. (p. 38) Hybrids. 7. (p. 37) -άνω, -ύνω, -σκω, -ίσκω. 8. (p. 39) 'Irregular' 9. (p. 40) Consonant changes in perfect passive. 10. (p. 40) "Infixes": what they are. 11. (p. 41) Irregular Reduplications and Augments. 12. (p. 42) Irregular (-μι-verb-like) 2nd Aorist Forms. 43 VII.A Perfect tense (meaning of), by D. B. Monro 44 VIII. Conditions 45 IX. Indirect Discourse: Moods in. (p. 43 the same restated) 47 X. Interrogative Pronouns & Indirect Question 49 XI. Relative Clauses. 52 XII. Constructions with words meaning "BEFORE" and "UNTIL" 53 XIII. -

Subject and Predicate: Peripheral Zones

Journal of Critical Reviews ISSN- 2394-5125 Vol 7, Issue 3, 2020 Review Article SUBJECT AND PREDICATE: PERIPHERAL ZONES OLGA G. SHEVCHENKO1 1Associate Professor, Candidate of Philological Sciences, the Head of Foreign Languages and Translation Studies Department, Philology and Inter-Cultural Communication Faculty, Vitus Bering Kamchatka State University, Petropavlovsk-Kamchatskiy, Russia. Received: 07.11.2019 Revised: 17.12.2019 Accepted: 25.01.2020 Abstract The prototypical method is one of the most important achievements of cognitive grammar. It can be efficiently employed in describing grammatical categories, both morphological and syntactic. The system of parts of the sentence reveals the existence of the prototype, periphery, and intermediary phenomena. The given paper deals with peripheral and intermediary phenomena in the sphere of the principal parts of the sentence. The nominative-with-the-infinitive construction presents an intermediary phenomenon as one of its elements bears the features of both the subject and the predicate. Peripheral and intermediary phenomena in the field of the predicate are often to be found in sentences with poly functional verbs, among them the verb to be. The grammatical status of the element following this verb is hard to define. Keywords: Prototype, Periphery, Intermediary Zone, Subject, Predicate, Object, Apposition, Adverbial Modifier. © 2019 by Advance Scientific Research. This is an open-access article under the CC BY license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.31838/jcr.07.03.30 INTRODUCTION Nowadays cognitive linguistics has become popular in studying a So the main principles of the prototypical method of lot of branches of language science. -

VERBAL MORPHOLOGY 4.0 Introduction and Overview of Verbal

CHAPTER FOUR VERBAL MORPHOLOGY 4.0 Introduction and Overview of Verbal Inflection The majority of verbs in ANA can be analysed as having a triliteral root. There is also a sizeable group of verbs with quadriliteral roots and a limited number of verbs with pentaliteral roots. Verbs from a triliteral root may be conjugated in one of three stems. Stem I evolved primarily from the OA pәʿal stem, Stem II evolved primarily from the OA paʿʿel stem, and Stem III evolved out of the OA ʾapʿel stem.1 A comparison of the principal parts of each of the three stems for strong2 verbal roots is set out below. In what follows, the letters V, W, X, Y and Z are used to represent any strong consonants: The following are the principal parts of the ANA verb: Stem I Stem II Stem III Imperative XYoZ mXăYәZ maXYәZ Present Base XaYәZ- mXaYәZ- maXYәZ- Past Base XYәZ- mXoYәZ- muXYәZ- Stative Participle XYiZa mXuYZa múXYәZa / m\ŭXәYZa Infinitive XYaZa mXaYoZe maXYoZe The imperative and infinitive of the ancestor stems of Stem II and Stem III (i.e. OA paʿʿel and ʾap̱ʾel respectively) did not regularly exhibit a prefixed m-, although the ancestor forms of the present base, the past base and the stative participle (i.e. the OA participles) did. In ANA, this prefix has spread by analogy throughout all the parts of both Stem II and Stem III verbs, without exception. Verbs from quadriliteral roots are divided into two classes. The principal parts of both are given below: 1 The other common stems of OA have not developed into stems in ANA in a uniform manner.