Teaching Greek Verbs: a Manifesto

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greek Verb Aspect

Greek Verb Aspect Paul Bell & William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 21, 2012 The technical literature concerning aspect is vast and difficult. The goal of this tutorial is to present, as gently as possible, a few more or less commonly held opinions about aspect. Although these opinions may be championed by one academic quarter and denied by another, at the very least they should shed some light on an abstruse matter. Introduction The word “aspect” has its roots in the Latin verb specere meaning “to look at.” Aspect is concerned with how we view a particular situation. Hence aspect is subjective – different people will view the same situation differently; the same person can view a situation differently at different times. There is little doubt that how we see things depends on our psychological state at the mo- ment of seeing. The ‘choice’ to bring some parts of a situation into close, foreground relief while relegating others to an almost non-descript background happens unconsciously. But for one who must describe a situation to others, this choice may indeed operate consciously and deliberately. Hence aspect concerns not only how one views a situation, but how he chooses to relate, to re-present, a situation. A Definition of Aspect But we still haven’t really said what aspect is. So here’s a working definition – aspect is the dis- closure of a situation from the perspective of internal temporal structure. To put it another way, when an author makes an aspectual choice in relating a situation, he is choosing to reveal or conceal the situation’s internal temporal structure. -

The Dialect of Elis and Its Position Within the Greek Dialectological System MA-Thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations

The dialect of Elis and its position within the Greek dialectological system MA-thesis for the Master Classics and Ancient Civilisations Le site antique d’Olympie, illustration taken from Minon 2007 : 559 by M.J. van der Velden BA supervisors: dr. L. van Beek dr. A. Rademaker 2015-17 Universiteit Leiden Table of contents i. Acknowledgements ii. List of abbreviations 0. Introduction 1. The dialect features of Elean 1.1 West Greek features 1.1.1 West Greek phonological features 1.1.2 West Greek morphological features 1.1.3 Conclusion 1.2 Northwest Greek features 1.2.1 Northwest Greek phonological features 1.2.2 Northwest Greek morphological features 1.2.3 Conclusion 1.3 Features in common with various other dialects 1.3.1 Phonological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.2 Morphological features in common with various other dialects 1.3.3 Conclusion 1.4 Specifically Elean features 1.4.1 Specifically Elean phonological features 1.4.2 Specifically Elean morphological features 1.4.3 Conclusion 1.5 General conclusion 2. Evaluation 2.1 The consonant stem accusative plural in -ες 2.2 The consonant stem dative plural endings -οις and -εσσι 2.3 The middle participle in /-ēmenos/ 2.4 The development *ē > ǟ 2.5 The development *ӗ > α 2.6 The development *i > ε 3. Conclusion 4. Bibliography 2 Acknowledgements First of all, I would like to express my deepest gratitude towards Lucien van Beek for supervising my work, without whose help, comments and – at times necessary – incitations this study would not have reached its current shape, as well as towards Adriaan Rademaker for carefully reading my work and sharing his remarks. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran

Tense, Time, Aspect and the Ancient Greek Verb by Jerome Moran early every – no, every – Greek The questions in the first sentence 3. In Greek the tense of a verb may Ngrammar and course book, even (‘deliberative’ questions, therefore in denote something different from or the most comprehensive (in English, the subjunctive) refer to present (or additional to the time at which the at any rate), gives a very skimpy, perhaps future) time. But one of act, event, occurrence, process, state perfunctory and unhelpful account — the verbs (εἴπωμεν) is in a past denoted by the verb is located. In insofar as it gives any account at all – of tense (aorist). The second sentence particular, it may denote something what ‘aspect’ is and how exactly it is refers to past time, but one of the called ‘aspect’. related to verb tense and time (which verbs (βούλοιτο) is in the present tend to be conflated). Most of the tense. 4. Whether the tense of a Greek verb books and articles on the subject of denotes time or/and aspect depends the aspect of the Greek verb are What is going on? The answer is in the first place on the mood of the accessible only to the professional something called ‘aspect’, and its verb (‘the form which a verb philologist, and can’t therefore be connection with tense and time. Just assumes in order to reflect the easily applied by non-specialists to the note for now a difference in the manner (modus) in which the speaker understanding of the actual usage of kind of things denoted by the verbs conceives the action’ (Woodcock)). -

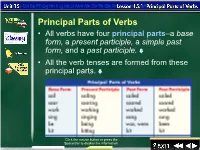

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

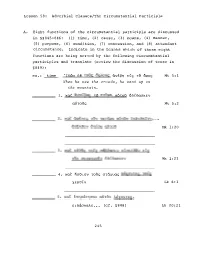

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight

Lesson 58: Adverbial Clauses/The Circumstantial Participle A. Eight functions of the circumstantial participle are discussed in §§845-846: (1) time, (2) cause, (3) means, (4) manner, (5) purpose, (6) condition, (7) concession, and (8) attendant circumstance. Indicate in the blanks which of these eight functions are being served by the following circumstantial participles and translate (review the discussion of tense in §849) : ex.: time -Iowv o� �o�� 5XAOU� aVE�n EL� �b 5po� Mt 5:1 When he saw the orowds, he went up on the mountain. 1. Kat avoLEa� �b o�oHa au�ou EOLoaoKEv au�o�� Mt 5:2 Mk 1:20 Mk 1:21 4. Kat no8Lov �o�� o�axua� WWXOV�E� �aC� XEPOLV Lk 6:1 ALoaaKaAE • • • (cf. §848) Lk 20:21 245 246 6. xat &auuaoav�E� En� �fj anoxpCoE� au�oG EOCYnOav Lk 20:26 7. TaG�a �a pnua�a EAaAnOEv EV �� yako �uAaxl� o�oaoxwv EV �Q tEPQ In 8:20 Acts 10:27 B. As a modifier, a circumstantial participle agrees in gender, number and case with its antecedent (§8460) in the sentence unless it has its own subject in a genitive absolute con struction (§847). Underline the antecedents or subjects of the participles in the following sentences and translate (note §8470): 1. Ka�aBav�o� 08 au�ou an� �oG opou� nXOAou&noav au�� OXAO� nOAAol Mt 8:1 Mt 22:18 Mk 1:40 Mk 2:23 247 5. Kat AEYEL aULoL� tv tXElv� Lij nUEP� 6�Ca� YEVOUEVT)� Mk 4:3 5 c. Prepare Gal 1:11-24 (from selection #26) for class trans lation. -

The Aorist in Modern Armenian: Core Value and Contextual Meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos

The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos To cite this version: Anaid Donabedian-Demopoulos. The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual mean- ings. Zlatka Guentcheva. Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, pp.375 - 412, 2016, 9789027267610. 10.1075/slcs.172.12don. halshs-01424956 HAL Id: halshs-01424956 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-01424956 Submitted on 6 Jan 2017 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. The Aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings, in Guentchéva, Zlatka (ed.), Aspectuality and Temporality. Descriptive and theoretical issues, John Benjamins, 2016, p. 375-411 (the published paper miss examples written in Armenian) The aorist in Modern Armenian: core values and contextual meanings Anaïd Donabédian (SeDyL, INALCO/USPC, CNRS UMR8202, IRD UMR135) Introduction Comparison between particular markers in different languages is always controversial, nevertheless linguists can identify in numerous languages a verb tense that can be described as aorist. Cross-linguistic differences exist, due to the diachrony of the markers in question and their position within the verbal system of a given language, but there are clearly a certain number of shared morphological, syntactic, semantic and/or pragmatic features. -

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615

30. Tense Aspect Mood 615 Richards, Ivor Armstrong 1936 The Philosophy of Rhetoric. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Rockwell, Patricia 2007 Vocal features of conversational sarcasm: A comparison of methods. Journal of Psycho- linguistic Research 36: 361−369. Rosenblum, Doron 5. March 2004 Smart he is not. http://www.haaretz.com/print-edition/opinion/smart-he-is-not- 1.115908. Searle, John 1979 Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Seddiq, Mirriam N. A. Why I don’t want to talk to you. http://notguiltynoway.com/2004/09/why-i-dont-want- to-talk-to-you.html. Singh, Onkar 17. December 2002 Parliament attack convicts fight in court. http://www.rediff.com/news/ 2002/dec/17parl2.htm [Accessed 24 July 2013]. Sperber, Dan and Deirdre Wilson 1986/1995 Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Oxford: Blackwell. Voegele, Jason N. A. http://www.jvoegele.com/literarysf/cyberpunk.html Voyer, Daniel and Cheryl Techentin 2010 Subjective acoustic features of sarcasm: Lower, slower, and more. Metaphor and Symbol 25: 1−16. Ward, Gregory 1983 A pragmatic analysis of epitomization. Papers in Linguistics 17: 145−161. Ward, Gregory and Betty J. Birner 2006 Information structure. In: B. Aarts and A. McMahon (eds.), Handbook of English Lin- guistics, 291−317. Oxford: Basil Blackwell. Rachel Giora, Tel Aviv, (Israel) 30. Tense Aspect Mood 1. Introduction 2. Metaphor: EVENTS ARE (PHYSICAL) OBJECTS 3. Polysemy, construal, profiling, and coercion 4. Interactions of tense, aspect, and mood 5. Conclusion 6. References 1. Introduction In the framework of cognitive linguistics we approach the grammatical categories of tense, aspect, and mood from the perspective of general cognitive strategies. -

Sequence-Of-Tense and the Features of Finite Tenses Karen Zagona University of Washington*

Sequence-of-tense and the Features of Finite Tenses Karen Zagona University of Washington* Abstract Sequence-of-tense (SOT) is often described as a (past) tense verb form that does not correspond to a semantically interpretable tense. Since SOT clauses behave in other respects like finite clauses, the question arises as to whether the syntactic category Tense has to be distinguished from the functional category tense. I claim that SOT clauses do in fact contain interpretable PRESENT tense. The “past” form is analyzed as a manifestation of agreement with the (matrix past) controller of the SOT clause evaluation time. One implication of this analysis is that finite verb forms should be analyzed as representing features that correspond to functional categories higher in clause structure, including those of the clausal left periphery. SOT morphology then sheds light on the existence of a series of finer- grained functional heads that contribute to tense construal, and to verbal paradigms. These include Tense, Modality and Force. 1. Introduction The phenomenon of sequence-of-tense (SOT) poses several challenges for the standard assumption that a “past tense” verb form signals the presence of a functional category in clause structure with an interpretable ‘past’ value. SOT is illustrated by the ‘simultaneous’ reading of sentence (1): (1) Terry believed that Sue was pregnant. a. The time of Sue’s pregnancy precedes time of Terry’s belief (precedence) b. The time of Sue’ pregnancy overlaps time of Terry’s belief (simultaneity) For the ‘precedence’ reading in (1a), the embedded clause tense is semantically transparent in the sense that the past form was corresponds to a past ordering relation (relative to the time of Terry’s belief). -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

The Indo-European K-Aorist

Frederik Kortlandt, Leiden University, www.kortlandt.nl The Indo-European k-aorist Ten years ago I wrote (2007: 155f.): “It has been impossible to establish an original meaning for the alleged velar suffix in the root aorists fēcī and iēcī (cf. Untermann 1993). I therefore think that we have to look for a phonetic explanation. Since the -k- is limited to the singular in the Greek active aorist indicative, I am h inclined to regard fēc- as the phonetic reflex of monosyllabic *dhēk < *d eH1t, where *-k- may have been either an intrusive consonant after the laryngeal before the final *-t, like -p- in Latin emptus ‘bought’ or *-s- in Hittite ezta ‘he ate’ < *edto, or a remnant of the Indo-Uralic velar consonant from which the laryngeal developed, as in Finnish teke- ‘make’ (cf. Kortlandt 2002: 220). The present stems of faciō and iaciō support the former possibility. This would also account for Tocharian A tāk, B tāka ‘became’, h h which reflect *steH2t. In a similar vein I reconstruct *hēp < *g eH1b t and *sēp < *seH1pt for Oscan hipid, hipust ‘will hold’, sipus ‘knowing’. While Oscan hafiest ‘will hold’ is in accordance with the Latin, Celtic and Germanic evidence, Umbrian hab- suggests that h h h *g eH1b - yielded *g eb- with preglottalized *-b- at an early stage and that this root- final consonant was generalized in Italic. It appears that Latin capiō ‘take’ < *kH2p- adopted the -ē- of cēpī from its synonym apiō, ēpī, and that scabō, scābī ‘scratch’ reflects original *skebh- (cf. Schrijver 1991: 431).” As Untermann observes (1993: 463), the Latin stems fac- and iac- behave as roots of primary verbs, and the same holds for Sabellic and Venetic. -

The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor

THE GRAMMAR OF FEAR: MORPHOSYNTACTIC METAPHOR IN FEAR CONSTRUCTIONS by HOLLY A. LAKEY A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2016 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Holly A. Lakey Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Linguistics by: Dr. Cynthia Vakareliyska Chairperson Dr. Scott DeLancey Core Member Dr. Eric Pederson Core Member Dr. Zhuo Jing-Schmidt Institutional Representative and Dr. Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2016. ii © 2016 Holly A. Lakey iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Holly A. Lakey Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics March 2016 Title: The Grammar of Fear: Morphosyntactic Metaphor in Fear Constructions This analysis explores the reflection of semantic features of emotion verbs that are metaphorized on the morphosyntactic level in constructions that express these emotions. This dissertation shows how the avoidance or distancing response to fear is mirrored in the morphosyntax of fear constructions (FCs) in certain Indo-European languages through the use of non-canonical grammatical markers. This analysis looks at both simple FCs consisting of a single clause and complex FCs, which feature a subordinate clause that acts as a complement to the fear verb in the main clause. In simple FCs in some highly-inflected Indo-European languages, the complement of the fear verb (which represents the fear source) is case-marked not accusative but genitive (Baltic and Slavic languages, Sanskrit, Anglo-Saxon) or ablative (Armenian, Sanskrit, Old Persian).