Phonological Aspects of Western Nilotic Mutation Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T3 Sandhi Rules of Different Prosodic Hierarchies

T3 Sandhi rules of different prosodic hierarchies Abstract This study conducts acoustic analysis on T3 sandhi of two characters across different boundaries of prosodic hierarchies. The experimental data partly support Chen (2000)’s view about sandhi domain that “T3 sandhi takes place obligatorily within MRU”, and “sandhi rule can not apply cross intonation phrase boundary”. Nonetheless, the results do not support his claim that “there are no intermediate sandhi hierarchies between MRU and intonation phrase”. On the contrary, it is found that, although T3 sandhi could occur across all kinds of hierarchical boundaries between MRU and intonation phrase, T3 sandhi rules within a foot (prosodic word), or between foots without pause, or between pauses without intonation (phonology phrase) are very different in terms of acoustic properties. Furthermore, based on the facts that (1) T3 sandhi could occur cross boundary of pauses and (2) phrase-final sandhi could be significantly lengthening, it is argued that T3 sandhi is due to dissimilation of low tones, rather than duration reduction within MRU domain. It is also demonstrated that tone sandhi and prosodic hierarchies may not be equivalently evaluated in Chinese phonology. Prosodic hierarchies are determined by pause and lengthening, not by tone sandhi. Key words: tone sandhi; prosodic hierarchies; boundary; Mandarin Chinese 1 Introduction So-called T3 sandhi in mandarin Chinese has been widely discussed in Chinese Phonology. Mandarin Chinese has four tones: T1 (level 55), T2 (rising 35), T3 (low-rise 214), T4 (falling 51).Generally, when a T3 is followed by another T3, it turns into T2. The rule could be simply stated as: 214->35/ ___214. -

The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology

This page intentionally left blank The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Phonology – the study of how the sounds of speech are represented in our minds – is one of the core areas of linguistic theory, and is central to the study of human language. This state-of-the-art handbook brings together the world’s leading experts in phonology to present the most comprehensive and detailed overview of the field to date. Focusing on the most recent research and the most influential theories, the authors discuss each of the central issues in phonological theory, explore a variety of empirical phenomena, and show how phonology interacts with other aspects of language such as syntax, morph- ology, phonetics, and language acquisition. Providing a one-stop guide to every aspect of this important field, The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology will serve as an invaluable source of readings for advanced undergraduate and graduate students, an informative overview for linguists, and a useful starting point for anyone beginning phonological research. PAUL DE LACY is Assistant Professor in the Department of Linguistics, Rutgers University. His publications include Markedness: Reduction and Preservation in Phonology (Cambridge University Press, 2006). The Cambridge Handbook of Phonology Edited by Paul de Lacy CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS Cambridge, New York, Melbourne, Madrid, Cape Town, Singapore, São Paulo Cambridge University Press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 8RU, UK Published in the United States of America by Cambridge University Press, New York www.cambridge.org Information on this title: www.cambridge.org/9780521848794 © Cambridge University Press 2007 This publication is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provision of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. -

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

Phonological Domains Within Blackfoot Towards a Family-Wide Comparison

Phonological domains within Blackfoot Towards a family-wide comparison Natalie Weber 52nd algonquian conference yale university October 23, 2020 Outline 1. Background 2. Two phonological domains in Blackfoot verbs 3. Preverbs are not a separate phonological domain 4. Parametric variation 2 / 59 Background 3 / 59 Consonant inventory Labial Coronal Dorsal Glottal Stops p pː t tː k kː ʔ <’> Assibilants ts tːs ks Pre-assibilants ˢt ˢtː Fricatives s sː x <h> Nasals m mː n nː Glides w j <y> (w) Long consonants written with doubled letters. (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 4 / 59 Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ /a+o/ ! [ɔː] Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Vowel inventory front central back high i iː o oː mid ɛː <ai> ɔː <ao> low a aː Predictable mid vowels? (Frantz 2017) Many [ɛː] and [ɔː] arise from coalescence across boundaries ◦ /a+i/ ! [ɛː] ◦ ! /a+o/ [ɔː] (Derrick and Weber n.d.; Weber 2020) 5 / 59 Contrastive mid vowels Some [ɛː] and [ɔː] are morpheme-internal, in overlapping environments with other long vowels JɔːníːtK JaːníːtK aoníít aaníít [ao–n/i–i]–t–Ø [aan–ii]–t–Ø [hole–by.needle/ti–ti1]–2sg.imp–imp [say–ai]–2sg.imp–imp ‘pierce it!’ ‘say (s.t.)!’ (Weber 2020) 6 / 59 Syntax within the stem Intransitive (bi-morphemic) vs. syntactically transitive (trimorphemic). Transitive V is object agreement (Quinn 2006; Rhodes 1994) p [ root –v0 –V0 ] Stem type Gloss ikinn –ssi AI ‘he is warm’ ikinn –ii II ‘it is warm’ itap –ip/i –thm TA ‘take him there’ itap –ip/ht –oo TI ‘take it there’ itap –ip/ht –aki AI(+O) ‘take (s.t.) there’ (Déchaine and Weber 2015, 2018; Weber 2020) 7 / 59 Syntax within the verbal complex Template p [ person–(preverb)*– [ –(med)–v–V ] –I0–C0 ] CP vP root vP CP ◦ Minimal verbal complex: stem plus suffixes (I0,C0). -

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M

5 Phonology Florian Lionnet and Larry M. Hyman 5.1. Introduction The historical relation between African and general phonology has been a mutu- ally beneficial one: the languages of the African continent provide some of the most interesting and, at times, unusual phonological phenomena, which have con- tributed to the development of phonology in quite central ways. This has been made possible by the careful descriptive work that has been done on African lan- guages, by linguists and non-linguists, and by Africanists and non-Africanists who have peeked in from time to time. Except for the click consonants of the Khoisan languages (which spill over onto some neighboring Bantu languages that have “borrowed” them), the phonological phenomena found in African languages are usually duplicated elsewhere on the globe, though not always in as concen- trated a fashion. The vast majority of African languages are tonal, and many also have vowel harmony (especially vowel height harmony and advanced tongue root [ATR] harmony). Not surprisingly, then, African languages have figured dispro- portionately in theoretical treatments of these two phenomena. On the other hand, if there is a phonological property where African languages are underrepresented, it would have to be stress systems – which rarely, if ever, achieve the complexity found in other (mostly non-tonal) languages. However, it should be noted that the languages of Africa have contributed significantly to virtually every other aspect of general phonology, and that the various developments of phonological theory have in turn often greatly contributed to a better understanding of the phonologies of African languages. Given the considerable diversity of the properties found in different parts of the continent, as well as in different genetic groups or areas, it will not be possible to provide a complete account of the phonological phenomena typically found in African languages, overviews of which are available in such works as Creissels (1994) and Clements (2000). -

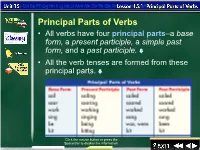

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

ELISION in ESAHIE Victoria Owusu Ansah Abstract One of the Syllable Structure Changes That Occur in Rapid Speech Because of Sounds Influencing Each Other Is Elision

Ghana Journal of Linguistics 9.2: 22-43 (2020) ________________________________________________________________________ http://dx.doi.org/10.4314/gjl.v9i2.2 ELISION IN ESAHIE Victoria Owusu Ansah Abstract One of the syllable structure changes that occur in rapid speech because of sounds influencing each other is elision. This paper provides an account of elision in Esahie, also known as Sehwi, a Kwa language spoken in the Western North region of Ghana. The paper discusses the processes involved in elision, and the context within which elision occurs in the language. The paper shows that sound segments, syllables and tones are affected by the elision process. It demonstrates that elision, though purely a phonological process, is influenced by morphological factors such as vowel juxtapositioning during compounding, and at word boundary. The evidence in this paper show that there is an interface between phonology and morphology when accounting for elision in Esahie. Data for this study were gathered from primary sources using ethnographic and stimuli methods. Keywords: Elision, Esahie, Sehwi, Tone, Deletion, Phonology 1.0 Introduction This paper provides an account of elision in Esahie, a Kwa language spoken in the Western North Region of Ghana1. It discusses the processes involved in elision in Esahie, and the context within which elision occurs in the language. The paper demonstrates that elision is employed in Esahie as a syllable structure repair mechanism. Elision is purely a phonological process but can sometimes be triggered by morphological factors. Indeed, the works of (Abakah 2004a, 2004b), Abdul-Rahman (2013), Abukari (2018), Becker and Gouskova (2016) writing on Akan, Dagbani and Russia respectively, confirm that elision 1 Speakers of Esahie in Ghana number about 580,000 and they live mostly in the Western North Region of the country (Ghana Statistical Service Report 2012, 2010 National Population Census). -

The Role of Morphology in Generative Phonology, Autosegmental Phonology and Prosodic Morphology

Chapter 20: The role of morphology in Generative Phonology, Autosegmental Phonology and Prosodic Morphology 1 Introduction The role of morphology in the rule-based phonology of the 1970’s and 1980’s, from classic GENERATIVE PHONOLOGY (Chomsky and Halle 1968) through AUTOSEGMENTAL PHONOLOGY (e.g., Goldsmith 1976) and PROSODIC MORPHOLOGY (e.g., McCarthy & Prince 1999, Steriade 1988), is that it produces the inputs on which phonology operates. Classic Generative, Autosegmental, and Prosodic Morphology approaches to phonology differ in the nature of the phonological rules and representations they posit, but converge in one key assumption: all implicitly or explicitly assume an item-based morphological approach to word formation, in which root and affix morphemes exist as lexical entries with underlying phonological representations. The morphological component of grammar selects the morphemes whose underlying phonological representations constitute the inputs on which phonological rules operate. On this view of morphology, the phonologist is assigned the task of identifying a set of general rules for a given language that operate correctly on the inputs provided by the morphology of that language to produce grammatical outputs. This assignment is challenging for a variety of reasons, sketched below; as a group, these reasons helped prompt the evolution from classic Generative Phonology to its Autosegmental and Prosodic descendants, and have since led to even more dramatic modifications in the way that morphology and phonology interact (see Chapter XXX). First, not all phonological rules apply uniformly across all morphological contexts. For example, Turkish palatal vowel harmony requires suffix vowels to agree with the preceding stem vowels (paşa ‘pasha’, paşa-lar ‘pasha-PL’; meze ‘appetizer’, meze-ler ‘appetizer-PL’) but does not apply within roots (elma ‘apple’, anne ‘mother’). -

Old and Middle Welsh David Willis ([email protected]) Department of Linguistics, University of Cambridge

Old and Middle Welsh David Willis ([email protected]) Department of Linguistics, University of Cambridge 1 INTRODUCTION The Welsh language emerged from the increasing dialect differentiation of the ancestral Brythonic language (also known as British or Brittonic) in the wake of the withdrawal of the Roman administration from Britain and the subsequent migration of Germanic speakers to Britain from the fifth century. Conventionally, Welsh is treated as a separate language from the mid sixth century. By this time, Brythonic speakers, who once occupied the whole of Britain apart from the north of Scotland, had been driven out of most of what is now England. Some Brythonic-speakers had migrated to Brittany from the late fifth century. Others had been pushed westwards and northwards into Wales, western and southwestern England, Cumbria and other parts of northern England and southern Scotland. With the defeat of the Romano-British forces at Dyrham in 577, the Britons in Wales were cut off by land from those in the west and southwest of England. Linguistically more important, final unstressed syllables were lost (apocope) in all varieties of Brythonic at about this time, a change intimately connected to the loss of morphological case. These changes are traditionally seen as having had such a drastic effect on the structure of the language as to mark a watershed in the development of Brythonic. From this period on, linguists refer to the Brythonic varieties spoken in Wales as Welsh; those in the west and southwest of England as Cornish; and those in Brittany as Breton. A fourth Brythonic language, Cumbric, emerged in the north of England, but died out, without leaving written records, in perhaps the eleventh century. -

Assibilation Or Analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean Noun Stem-Endings*

Assibilation or analogy?: Reconsideration of Korean noun stem-endings* Ponghyung Lee (Daejeon University) This paper discusses two approaches to the nominal stem-endings in Korean inflection including loanwords: one is the assibilation approach, represented by H. Kim (2001) and the other is the analogy approach, represented by Albright (2002 et sequel) and Y. Kang (2003b). I contend that the assibilation approach is deficient in handling its underapplication to the non-nominal categories such as verb. More specifically, the assibilation approach is unable to clearly explain why spirantization (s-assibilation) applies neither to derivative nouns nor to non-nominal items in its entirety. By contrast, the analogy approach is able to overcome difficulties involved with the assibilation position. What is crucial to the analogy approach is that the nominal bases end with t rather than s. Evidence of t-ending bases is garnered from the base selection criteria, disparities between t-ending and s-ending inputs in loanwords. Unconventionally, I dare to contend that normative rules via orthography intervene as part of paradigm extension, alongside semantic conditioning and token/type frequency. Keywords: inflection, assibilation, analogy, base, affrication, spirantization, paradigm extension, orthography, token/type frequency 1. Introduction When it comes to Korean nominal inflection, two observations have captivated our attention. First, multiple-paradigms arise, as explored in previous literature (K. Ko 1989, Kenstowicz 1996, Y. Kang 2003b, Albright 2008 and many others).1 (1) Multiple-paradigms of /pʰatʰ/ ‘red bean’ unmarked nom2 acc dat/loc a. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰatʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e b. pʰat pʰaʧʰ-i pʰaʧʰ-ɨl pʰatʰ-e c. -

Consonant Mutation and Reduplication in Blin Singulars and Plurals

Consonant Mutation and Reduplication in Blin Singulars and Plurals Paul D. Fallon Howard University 1. Introduction Blin1, a Central Cushitic (Agaw) language of Eritrea, displays a complex series of consonant mutations between plural and singular forms, with several unusual properties. This paper describes several such properties, focusing on consonant mutation (or apophony), especially in relation to reduplication, using Correspondence Theory (McCarthy and Prince 1995) within the overall framework of Optimality Theory, drawing on data based on both published sources (e.g. Lamberti and Tonelli 1997) and the author's fieldwork in Eritrea. This paper describes the rare interaction between mutation and reduplication, and provides additional support for Mc Laughlin's (2000) analysis of mutation as the result of featural affixation (Akinlabi 1996, Zoll 1998) to the root node of a consonant. However, unlike Mc Laughlin's analysis, where mutation was stem-initial, in Blin such mutation is stem-final. One of the more unusual properties of Blin is that for phonological purposes, it is often easier to take the plural as the underlying form, since singulars and singulatives are morphologically marked. For example, /kr/ 'stones' has a singular /kr-a/. One common mutation is the lenition of velar stops: /lk/ 'fires', /lx-a/ (sg.). The loss of continuancy also results in the loss of ejection (/ak'/ → /ax-a/ 'cave (pl./sg.)', but not labialization /kin/ → /xin-a/ 'woman (pl./sg.)', /sak’/ → /sax-a/ 'fat (n.)(pl./sg.)'. In addition, velar lenition may occur word-medially, e.g. [bkl] → [bxl-a] 'mule (pl./sg.)'. More than one mutation process may also occur within the word: /dk’l/ → /dxar-a/ 'donkey (pl./sg.)'. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology.