Islands of Resilience: the History of the German Strong Verbs from a Systemic Point of View*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

The English Language

The English Language Version 5.0 Eala ðu lareow, tæce me sum ðing. [Aelfric, Grammar] Prof. Dr. Russell Block University of Applied Sciences - München Department 13 – General Studies Winter Semester 2008 © 2008 by Russell Block Um eine gute Note in der Klausur zu erzielen genügt es nicht, dieses Skript zu lesen. Sie müssen auch die “Show” sehen! Dieses Skript ist der Entwurf eines Buches: The English Language – A Guide for Inquisitive Students. Nur der Stoff, der in der Vorlesung behandelt wird, ist prüfungsrelevant. Unit 1: Language as a system ................................................8 1 Introduction ...................................... ...................8 2 A simple example of structure ..................... ......................8 Unit 2: The English sound system ...........................................10 3 Introduction..................................... ...................10 4 Standard dialects ................................ ....................10 5 The major differences between German and English . ......................10 5.1 The consonants ................................. ..............10 5.2 Overview of the English consonants . ..................10 5.3 Tense vs. lax .................................. ...............11 5.4 The final devoicing rule ....................... .................12 5.5 The “th”-sounds ................................ ..............12 5.6 The “sh”-sound .................................. ............. 12 5.7 The voiced sounds / Z/ and / dZ / ...................................12 5.8 The -

0Gpresentparticiples.Pdf

http://www.ToLearnEnglish.com − Resources to learn/teach English (courses, games, grammar, daily page...) Present Participles > Formation The present participle is formed by adding the ending "−−ing" to the infinitive (dropping any silent "e" at the end of the infinitive): to sing −−> singing to take −−> taking to bake −−> baking to be −−> being to have −−> having > Use A. The present participle may often function as an adjective: That's an interesting book. That tree is a weeping willow. B. The present participle can be used as a noun denoting an activity (this form is also called a gerund): Swimming is good exercise. Traveling is fun. C. The present participle can indicate an action that is taking place, although it cannot stand by itself as a verb. In these cases it generally modifies a noun (or pronoun), an adverb, or a past participle: Thinking myself lost, I gave up all hope. Washing clothes is not my idea of a job. Looking ahead is important. D. The present participle may be used with "while" or "by" to express an idea of simultaneity ("while") or causality ("by") : He finished dinner while watching television. By using a dictionary he could find all the words. While speaking on the phone, she doodled. By calling the police you saved my life! E. The present participle of the auxiliary "have" may be used with the past participle to describe a past condition resulting in another action: Having spent all his money, he returned home. Having told herself that she would be too late, she accelerated. TEST A) Find the gerund: 1. -

6 X 10.Long New.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-61803-8 - German: A Linguistic Introduction Sarah M. B. Fagan Index More information Index abbreviation 102, 258–260 analytic language 111n.45, 199 ablaut 57, 75, 80, 88, 97, 107, 113n.72, 186 anaphor 142 (Der) Abrogans 188 Anglo-Americanism 275–276 A.c.I. construction 143 antonymy 150–152 acronym 102–104 apex 12 address, forms of 252–255 approximant 13, 48n.6 in FWG 270 arytenoid cartilages 4–5, 50n.36, 211n.15 history of 252–253 aspect 153–155 adjective 90, 116, 119, 259 habitual 122, 155 attributive 71, 110n.33, 124 imperfective 153–154 and case 120–122 perfective 153 comparative form 71, 150–151, 190 progressive 155, 161–163, 216 inflection of 70–75 aspiration 11, 21, 23–24, 49n.16, 184–185, predicative 71–72, 110n.33, 111n.35, 241n.1 124–125 Aspiration (rule) 23–24 strong endings 72 assimilation 21, 26, 190, 248 superlative form 71, 111n.35 in colloquial German 246 weak endings 72–73 see also Nasal Assimilation, Velar Fricative see also compound Assimilation, voicing assimilation adjective phrase 63, 124–125, 193–194 Auslautverhartung¨ , see Final Fortition extended 125, 278n.10 Auslautsgesetze (laws of finals) 212n.33 adjunct 128 Austrian Standard German (ASG) 224–228 adjunction 135–136, 141–142 grammar 226–227 adverb 92, 116, 124–126, 141–142, 146n.15, legal language 279n.21 250–251; see also compound pronunciation 225–226 adverb phrase 124–126, 176–177 vocabulary 227–228 affix 55–56, 99, 106, 212n.29 auxiliary verb 85, 113n.78, 116, 129, 197, 199, derivational 90, 108n.3 251, 270 inflectional 56, -

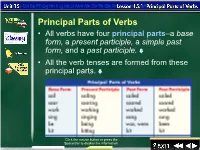

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

Verbals: Participle Or Gerund? | Verbals Worksheets

Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle or Gerund? A participle is a verb form that functions as an adjective in a sentence. A gerund is a verb form that functions as a noun in a sentence. Below are sentences using either a participle or a gerund. Read each sentence carefully. Write which verbal form appears in the sentence in the blank. 1. The jumping frog landed in her lap. _______________________________________________________________________________ 2. Lucinda had a calling to help other people. _______________________________________________________________________________ 3. The mother barely caught the crawling baby before he went into the street. _______________________________________________________________________________ 4. The house was filled with a haunting spector. _______________________________________________________________________________ 5. Running in the halls is strictly forbidden. _______________________________________________________________________________ 6. They won the award for caring for sick animals. _______________________________________________________________________________ 7. Paul bought new climbing gear. _______________________________________________________________________________ 8. Escaping was the only thought he had. _______________________________________________________________________________ Copyright © 2014 K12reader.com. All Rights Reserved. Free for educational use at home or in classrooms. www.k12reader.com Name: ___________________________Key VErbals: Participle -

New Arguments for Verb Cluster Formation at PF and a Right-Branching VP

New arguments for verb cluster formation at PF and a right-branching VP. Evidence from verb doubling and cluster penetrability* version October 12, 2013; to appear in Linguistic Variation Martin Salzmann, University of Leipzig ([email protected]) Abstract This paper provides new evidence that verb cluster formation in West Germanic takes place post- syntactically. Contrary to some previous accounts, I argue that cluster formation involves linearly adjacent morphosyntactic words and not syntactic sister nodes. The empirical evidence is drawn from Swiss German verb doubling constructions where intriguing asymmetries arise between ascending and descending orders. The approach additionally solves the cluster puzzle with extraposition and topicalization, generates all of the crosslinguistically attested six orders in the verbal complex and correctly predicts which orders are penetrable in which positions. On a more general level, the paper provides arguments for a derivational treatment of verb cluster formation and order variation and adduces important evidence in favor of a right-branching VP. 1 Introduction: Verb clusters in West Germanic In this section I will briefly lay out the central properties of West-Germanic verb clusters. Given the vast literature, I will confine myself to the aspects that will play a role in the ensuing discussion. For a detailed survey both over facts and analyses, the reader is referred to Wurmbrand (2005). West Germanic OV-languages are famous for their verb clusters, i.e. the phenomenon that the verbal elements of a clause all occur together clause-finally (under verb second, where the finite verb moves to C, only the non-finite verbs occur together). -

The Germanic Third Weak Class

THE GERMANIC THIRD WEAK CLASS JAY H. JASANOFF Harvard University Germanic verbs of the 3rd weak class form presents characterized by an alternation between predesinential *ai (e.g. Go. 3sg. habai1» and *a (e.g. Ipl. habam). These verbs are usually compared with the 'e-verbs' of Italic and Balto Slavic, but no IE present built on the stative suffix *-e- will account phonologi cally for the form of the suffix in Germanic. Instead, it can be shown that the characteristic Germanic paradigm results from the 'activization' of an older middle paradigm in which a 3sg. in *-ai « IE *-oi; cf. Skt. duh~ 'milks') was further suffixed by the productive active ending *-Pi « IE *-ti). 1. The inflection of the third class of weak verbs (exemplified by the verb 'to have': Gothic haban, Old Norse hafa,! Old High German hab~, Old Saxon hebbian, Old English habban) presents one of the classic problems in the historical morphology of Germanic. Not only do the verbs of this class show peculiarities in all the older Germanic languages, but they differ remarkably in their conjugation from one language to another, so that it is not at all obvious how the Common Germanic paradigm should be reconstructed. Given this diversity of forms, we will do well to begin with a short review of the morphological facts themselves. The situation is simplest in Old High German. The entire conjugation of hab~n is athematic (to the extent that this term still has any meaning), and is based on the single stem hab~-: 1sg. hab~, 3sg. hab~t, 3pl. -

Claire-Latinate English Treasure Hunt-2

Claire Blood-Cheney Latinate English Treasure Hunt Is Globalization Good for Women? By Alison M. Jaggar The term "globalization" is currently used to refer to the rapidly accelerating integration of many local and national economies into a single global market, regulated by the World Trade Organization, and to the political and cultural corollaries of this process. These developments, taken together, raise profound new questions for the humanities in general and for political philosophy in particular. Globalization in the broadest sense is nothing new. Intercontinental travel and trade, and the mixing of cultures and populations are as old as humankind; after all, the foremothers and forefathers of everyone of us walked originally out of Africa. Rather than being an unprecedented phenomenon, contemporary globalization may be seen as the culmination of long- term developments that have shaped the modern world. Specifically, for the last half millennium intercontinental trade and population migrations have mostly been connected with the pursuit of new resources and markets for the emerging capitalist economies of Western Europe and North America. European colonization and expansion may be taken as beginning with the onslaught on the Americas in 1492 and as continuing with the colonization of India, Africa, Australasia, Oceania and much of Asia. History tells of the rise and fall of many great empires, but the greatest empires of all came to exist only in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. It was primarily in consequence of European and U.S. expansion that the world became––and remains– –a single interconnected system. European and U.S. colonialism profoundly shaped the world we inhabit today. -

German Irregular Verbs Chart

GERMAN IRREGULAR VERBS CHART Infinitive Meaning Present Tense Imperfect Participle Tense (e.g. for Passive, & Perfect Tense) to… er/sie/es: ich & er/sie/es: backen bake backt backte gebacken befehlen command, order befiehlt befahl befohlen beginnen begin beginnt begann begonnen beißen bite beißt biss gebissen betrügen deceive, cheat betrügt betrog betrogen bewegen1 move bewegt bewog bewogen biegen bend, turn biegt bog (bin etc.) gebogen bieten offer, bid bietet bot geboten binden tie bindet band gebunden bitten request, ask bittet bat gebeten someone to do... blasen blow, sound bläst blies geblasen bleiben stay, remain bleibt blieb (bin etc.) geblieben braten roast brät briet gebraten brechen break bricht brach gebrochen brennen burn brennt brannte gebrannt bringen bring, take to... bringt brachte gebracht denken think denkt dachte gedacht dürfen be allowed to... darf durfte gedurft empfehlen recommend empfiehlt empfahl empfohlen erschrecken2 be frightened erschrickt erschrak (bin etc.) erschrocken essen eat3 isst aß gegessen fahren go (not on foot), fährt fuhr (bin etc.) gefahren drive fallen fall fällt fiel (bin etc.) gefallen fangen catch fängt fing gefangen finden find findet fand gefunden fliegen fly fliegt flog (bin etc.) geflogen fliehen flee, run away flieht floh (bin etc.) geflohen fließen flow fließt floss geflossen fressen eat (done by frisst fraß gefressen animals) frieren freeze, be cold friert fror (bin etc.) gefroren geben give gibt gab gegeben gedeihen flourish, prosper gedeiht gedieh (bin etc.) gediehen gehen go, walk geht ging (bin etc.) gegangen gelingen4 succeed gelingt gelang (bin etc.) gelungen gelten5 be valid, be of gilt galt gegolten worth 1 Also used as a reflexive verb, i.e. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology.