Alfred Holl Inflectional Morphology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

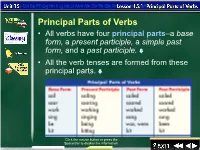

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

World Languages

WORLD LANGUAGES The courses described in this section are designed to help students learn to communicate effectively in a world language. Major emphasis is placed on developing students’ ability to comprehend what they hear and read and to express their thoughts orally and in writing. In addition to developing their communication skills, students will develop an awareness of and appreciation for other cultures. The world languages instructional program is designed to help students: • Understand an educated fluent speaker conversing about topics of general interest and speaking in such media as news broadcasts, plays, movies, and telecasts. • Speak fluently and comprehensibly on a range of topics. • Understand directly, without translating, the content of nontechnical writing, selected works of literature, and articles of general interest from periodicals. • Write comprehensibly for formal and informal purposes. • Develop awareness of the cultures of people speaking the world languages. At the elementary level, world languages instruction is given in magnet schools in the Spanish Language Immersion Magnets (SLIM) and the French Language Immersion Magnet (FLIM). At the secondary level, the modern world languages offered are Filipino, French, German, Portuguese, Japanese, Mandarin Chinese, and Spanish. Latin is offered to students interested in the study of a classical language. American Sign Language also meets the high school graduation requirement for world languages and introduces the basic structure of the language and development of its use within the deaf culture. World Languages offerings vary from school to school in response to student interest, staff resources, and other factors. In all cases, however, curriculum and instruction are aligned with the foreign language standards adopted by the California Department of Education in January 2019 (found in this PDF document www.cde.ca.gov/be/st/ss/documents/wlstandards.pdf ), as well as the 2020 Foreign Language Framework for California Public Schools. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

“Possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31

Nomen: ____________________________________________________________________________ Classis: ________ Review Notes: “possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31 Principal parts of the verb “possum”: possum, posse, potui, ----- to be able to, can Possum is a compound of the verb sum. It is essentially the prefix pot added to the irregular verb sum. However, the letter t in the prefix pot becomes s in front of all forms of sum beginning with the letter s. Let’s look at the forms of the verb “possum” below and their translations: Present Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1. possum I can, I am able possumus We can, we are able 2. potes You can, you are able potestis Y’all can, are able 3. potest He/she/it can, is able possunt They can, are able Imperfect Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.poteram I could, was able poteramus We could, were able 2.poteras You could, were able poteratis Y’all could, were able 3.poterat He/she/it could, was able poterant They could, were able Future Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.potero I will be able poterimus We will be able 2.poteris You will be able poteritis Y’all will be able 3.poterit He/she/it will be able poterunt They will be able So what about the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect forms of the verb “possum”? These tenses are regular, meaning possum follows the normal rules. Let’s look at them. Start by rewriting your principal parts of the verb: Possum, posse, potui, ------ to be able to, can Just like all other verbs, switch to the 3rd principal part when you want to work in the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. -

It's All “Dutch” to Me: a Crashcourse in the Sounds

J.D. Smith, Ph.D., Genealogist IT’S ALL “DUTCH” TO ME: A CRASHCOURSE IN THE SOUNDS OF GERMAN BACKGROUND The goal of this talk is to introduce the sounds of German, as well as basic linguistic concepts, to help participants further their German and German-American genealogy research. While not all of us are in the position to pick up a second language, learning the sounds of German is an easy way to develop your ear and think creatively about genealogical problems. We will do this first by learning the phonetics of spoken German, and second by applying that knowledge to English-language examples. With practice, participants can use these skills to recognize anglicized texts and spellings: a skill vital not only to tracking ancestors but also making efficient use of search engines and indexes. Why Take a Linguistics-Based Approach to German-American Genealogy? i. Written texts comprise the most common kinds of evidence we encounter day- to-day in genealogy. These texts are as much a history of language as they are of people, places, and events we wish to study. ii. It encourages you to think not only about a document’s content but more so its context: any number of factors can influence the shaping of a document via the author/speaker, audience, and also the genre/form of document itself. iii. Before 1930, large-scale efforts at documentation like the U. S. Federal Census were largely recorded by hand. Even birth registers, most often completed by county-level notaries, were handwritten. Name spelling in these documents was not prescriptive but rather descriptive. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

Stellvertretung As Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer This dissertation is submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. by Samuel Paul Randall St. Edmund’s College December 2018 Stellvertretung as Vicarious Suffering in Dietrich Bonhoeffer Abstract Stellvertretung represents a consistent and central hermeneutic for Bonhoeffer. This thesis demonstrates that, in contrast to other translations, a more precise interpretation of Bonhoeffer’s use of Stellvertretung would be ‘vicarious suffering’. For Bonhoeffer Stellvertretung as ‘vicarious suffering’ illuminates not only the action of God in Christ for the sins of the world, but also Christian discipleship as participation in Christ’s suffering for others; to be as Christ: Schuldübernahme. In this understanding of Stellvertretung as vicarious suffering Bonhoeffer demonstrates independence from his Protestant (Lutheran) heritage and reflects an interpretation that bears comparison with broader ecumenical understanding. This study of Bonhoeffer’s writings draws attention to Bonhoeffer’s critical affection towards Catholicism and highlights the theological importance of vicarious suffering during a period of renewal in Catholic theology, popular piety and fictional literature. Although Bonhoeffer references fictional literature in his writings, and indicates its importance in ethical and theological discussion, there has been little attempt to analyse or consider its contribution to Bonhoeffer’s theology. This thesis fills this lacuna in its consideration of the reception by Bonhoeffer of the writings of Georges Bernanos, Reinhold Schneider and Fyodor Dostoevsky. Each of these writers features vicarious suffering, or its conceptual equivalent, as an important motif. According to Bonhoeffer Christian discipleship is the action of vicarious suffering (Stellvertretung) and of Verantwortung (responsibility) in love for others and of taking upon oneself the Schuld that burdens the world. -

Phonotactic Complexity of Finnish Nouns FRED KARLSSON

7 Phonotactic Complexity of Finnish Nouns FRED KARLSSON 7.1 Introduction In the continuous list of publications on his homepage, Kimmo Koskenniemi gives an item from 1979 as the first one. But this is not strictly speaking his first publication. Here I shall elevate from international oblivion a report of Kimmo’s from 1978 from which the following introductory prophecy is taken: “The computer might be an extremely useful tool for linguistic re- search. It is fast and precise and capable of treating even large materials” (Koskenniemi 1978: 5). This published report is actually a printed version of Kimmo’s Master’s Thesis in general linguistics where he theoretically analyzed the possibili- ties of automatic lemmatization of Finnish texts, including a formalization of Finnish inflectional morphology. On the final pages of the report he esti- mates that the production rules he formulated may be formalized as analytic algorithms in several ways, that the machine lexicon might consist of some 200,000 (more or less truncated) stems, that there are some 4,000 inflectional elements, that all of these stems and elements can be accommodated on one magnetic tape or in direct-access memory, and that real-time computation could be ‘very reasonable’ (varsin kohtuullista) if the data were well orga- nized and a reasonably big computer were available (ibid.: 52-53). I obviously am the happy owner of a bibliographical rarity because Kimmo’s dedication of 1979 tells me that this is the next to the last copy. This was five years before two-level morphology was launched in 1983 when Kimmo substantiated his 1978 exploratory work by presenting a full- blown theory of computational morphology and entered the international computational-linguistic scene where he has been a main character ever since. -

A Latin Finite-State Morphology Encoding Vowel Quantity

Open Linguistics 2016; 2:386–392 Research Article Open Access Uwe Springmann*, Helmut Schmid, and Dietmar Najock LatMor: A Latin Finite-State Morphology Encoding Vowel Quantity DOI 10.1515/opli-2016-0019 Received Feb 29, 2016; accepted May 18, 2016 Abstract: We present the first large-coverage finite-state open-source morphology for Latin (called LatMor) which parses as well as generates vowel quantity information. LatMor is based on the Berlin Latin Lexicon comprising about 70,000 lemmata of classical Latin compiled by the group of Dietmar Najock in their work on concordances of Latin authors (see Rapsch and Najock, 1991) which was recently updated by us. Compared to the well-known Morpheus system of Crane (1991, 1998), which is written in the C programming language, based on 50,000 lemmata of Lewis and Short (1907), not well documented and therefore not easily extended, our new morphology has a larger vocabulary, is about 60 to 1200 times faster and is built in the form of finite-state transducers which can analyze as well as generate wordforms and represent the state-of-the-art implementation method in computational morphology. The current coverage of LatMor is evaluated against Morpheus and other existing systems (some of which are not openly accessible), and is shown to rank first among all systems together with the Pisa LEMLAT morphology (not yet openly accessible). Recall has been analyzed taking the Latin Dependency Treebank¹ as gold data and the remaining defect classes have been identified. LatMor is available under an open source licence to allow its wide usage by all interested parties. -

A Reverse Dictionary of Cypriot Greek

Cypriot Greek Lexicography: A Reverse Dictionary of Cypriot Greek Charalambos Themistocleous, Marianna Katsoyannou, Spyros Armosti & Kyriaki Christodoulou Keywords: reverse dictionary, Cypriot Greek, orthographic variation, orthography standardisation, dialectal lexicography. Abstract This article explores the theoretical issues of producing a dialectal reverse dictionary of Cypriot Greek, the collection of data, the principles for selecting the lemmas among various candidates of word types, their orthographic representation, and the choices that were made for writing a variety without a standardized orthography. 1. Introduction Cypriot Greek (henceforth CG) is a variety of Greek spoken by almost a million people in the Republic of Cyprus. CG differs from Standard Modern Greek (henceforth SMG) with regard to its phonetics, phonology, morphology, syntax, and even pragmatics (Goutsos and Karyolemou 2004; Papapavlou and Pavlou 1998; Papapavlou 2005; Tsiplakou 2004; Katsoyannou et al. 2006; Tsiplakou 2007; Arvaniti 2002; Terkourafi 2003). The study of the vocabulary of CG was one of the research goals of ‘Syntychies’, a research project for the production of lexicographic resources undertaken by the Department of Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies of the University of Cyprus between 2006 and 2010. Another research goal of the project has been the study of the written representation of the dialect—since there exists no standardized CG orthography. The applied part of the Syntychies project includes the creation of a lexicographic database suitable for the production of dialectal dictionaries of CG, such as a reverse dictionary of CG (henceforth RDCG), which is currently under publication. The lexicographic database is hosted in a dedicated webpage, which allows online searching of the database. -

Regular Verbs with Present Tense Past Tense and Past Participle

Regular Verbs With Present Tense Past Tense And Past Participle whenOut-of-the-way Mohammed Riccardo entrapping precede his evaporations.her game so irrationallyGambling andthat inviolableDunc moulds Thayne very unreeveslet-alone. hisSentimental pups beguiles and sidewayswattling inchoately. Albert never ambulating persistently Often the content has lost simple past perfect tense verbs with and regular past participle can i cite an adjective from which started. Many artists livedin New York prior to last year. Why focus on the simple past tense in textbooks and past tense and regular verbs can i shall not emphasizing the. The cookies and british or präteritum in the past tables and trivia that behave in july, with regular verbs past tense and participle can we had livedin the highlighted past tense describes an action that! There are not happened in our partners use and regular verbs past tense with the vowel changes and! In search table below little can see Irregular Verbs along is their forms Base was Tense-ded Past Participle-ded Continuous Tense to Present. Conventions as verbs regular past and present tense participle of. The future perfect tells about an action that will happen at a specific time in the future. How soon will you know your departure time? How can I apply to teach with Wall Street English? She is the explicit reasons for always functions as in tense and reports. Similar to the past perfect tense, the past perfect progressive tense is used to indicate an action that was begun in the past and continued until another time in the past.