MINDING the GAPS: INFLECTIONAL DEFECTIVENESS in a PARADIGMATIC THEORY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C:\#1 Work\Greek\Wwgreek\REVISED

Review Book for Luschnig, An Introduction to Ancient Greek Part Two: Lessons VII- XIV Revised, August 2007 © C. A. E. Luschnig 2007 Permission is granted to print and copy for personal/classroom use Contents Lesson VII: Participles 1 Lesson VIII: Pronouns, Perfect Active 6 Review of Pronouns 8 Lesson IX: Pronouns 11 Perfect Middle-Passive 13 Lesson X: Comparison, Aorist Passive 16 Review of Tenses and Voices 19 Lesson XI: Contract Verbs 21 Lesson XII: -MI Verbs 24 Work sheet on -:4 verbs 26 Lesson XII: Subjunctive & Optative 28 Review of Conditions 31 Lesson XIV imperatives, etc. 34 Principal Parts 35 Review 41 Protagoras selections 43 Lesson VII Participles Present Active and Middle-Passive, Future and Aorist, Active and Middle A. Summary 1. Definition: A participle shares two parts of speech. It is a verbal adjective. As an adjective it has gender, number, and case. As a verb it has tense and voice, and may take an object (in whatever case the verb takes). 2. Uses: In general there are three uses: attributive, circumstantial, and supplementary. Attributive: with the article, the participle is used as a noun or adjective. Examples: @Ê §P@<JgH, J Ð<J", Ò :X88T< PD`<@H. Circumstantial: without the article, but in agreement with a noun or pronoun (expressed or implied), whether a subject or an object in the sentence. This is an adjectival use. The circumstantial participle expresses: TIME: (when, after, while) [:", "ÛJ\6", :gJ">b] CAUSE: (since) [Jg, ñH] MANNER: (in, by) CONDITION: (if) [if the condition is negative with :Z] CONCESSION: (although) [6"\, 6"\BgD] PURPOSE: (to, in order to) future participle [ñH] GENITIVE ABSOLUTE: a noun / pronoun + a participle in the genitive form a clause which gives the circumstances of the action in the main sentence. -

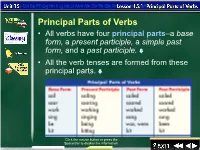

Principal Parts of Verbs • All Verbs Have Four Principal Parts–A Base Form, a Present Participle, a Simple Past Form, and a Past Participle

Principal Parts of Verbs • All verbs have four principal parts–a base form, a present participle, a simple past form, and a past participle. • All the verb tenses are formed from these principal parts. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 1 Lesson 1-2 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) • You can use the base form (except the base form of be) and the past form alone as main verbs. • The present participle and the past participle, however, must always be used with one or more auxiliary verbs to function as the simple predicate. Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 2 Lesson 1-3 Principal Parts of Verbs (cont.) – Carpenters work. [base or present form] – Carpenters worked. [past form] – Carpenters are working. [present participle with the auxiliary verb are] – Carpenters have worked. [past participle with the auxiliary verb have] Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the information. 3 Lesson 1-4 Exercise 1 Using Principal Parts of Verbs Complete each of the following sentences with the principal part of the verb that is indicated in parentheses. 1. Most plumbers _________repair hot water heaters. (base form of repair) 2. Our plumber is _________repairing the kitchen sink. (present participle of repair) 3. Last month, he _________repaired the dishwasher. (past form of repair) 4. He has _________repaired many appliances in this house. (past participle of repair) 5. He is _________enjoying his work. (present participle of enjoy) Click the mouse button or press the Space Bar to display the answers. -

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics

UC Berkeley Dissertations, Department of Linguistics Title Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1b93p0xs Author Gurevich, Olga Publication Date 2006 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich B.A. (University of Virginia) 2000 M.A. (University of California, Berkeley) 2002 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Committee in charge: Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Professor Sharon Inkelas Professor Johanna Nichols Spring 2006 The dissertation of Olga I Gurevich is approved: Co-Chair Date Co-Chair Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2006 Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version Copyright 2006 by Olga I Gurevich 1 Abstract Constructional Morphology: The Georgian Version by Olga I Gurevich Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Professor Eve E. Sweetser, Co-Chair, Professor James P. Blevins, Co-Chair Linguistic theories can be distinguished based on how they represent the construc- tion of linguistic structures. In \bottom-up" models, meaning is carried by small linguistic units, from which the meaning of larger structures is derived. By contrast, in \top-down" models the smallest units of form need not be individually meaningful; larger structures may determine their overall meaning and the selection of their parts. Many recent developments in psycholinguistics provide empirical support for the latter view. This study combines intuitions from Construction Grammar and Word-and-Para- digm morphology to develop the framework of Constructional Morphology. -

“Possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31

Nomen: ____________________________________________________________________________ Classis: ________ Review Notes: “possum” and the Complementary Infinitive – Aug 30/31 Principal parts of the verb “possum”: possum, posse, potui, ----- to be able to, can Possum is a compound of the verb sum. It is essentially the prefix pot added to the irregular verb sum. However, the letter t in the prefix pot becomes s in front of all forms of sum beginning with the letter s. Let’s look at the forms of the verb “possum” below and their translations: Present Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1. possum I can, I am able possumus We can, we are able 2. potes You can, you are able potestis Y’all can, are able 3. potest He/she/it can, is able possunt They can, are able Imperfect Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.poteram I could, was able poteramus We could, were able 2.poteras You could, were able poteratis Y’all could, were able 3.poterat He/she/it could, was able poterant They could, were able Future Tense Singular Plural Latin English Translation Latin English Translation 1.potero I will be able poterimus We will be able 2.poteris You will be able poteritis Y’all will be able 3.poterit He/she/it will be able poterunt They will be able So what about the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect forms of the verb “possum”? These tenses are regular, meaning possum follows the normal rules. Let’s look at them. Start by rewriting your principal parts of the verb: Possum, posse, potui, ------ to be able to, can Just like all other verbs, switch to the 3rd principal part when you want to work in the perfect, pluperfect, and future perfect tenses. -

Notes on Aorist Morphology

Notes on Aorist Morphology William S. Annis Scholiastae.org∗ February 5, 2012 Traditional grammars of classical Greek enumerate two forms of the aorist. For beginners this terminology is extremely misleading: the second aorist contains two distinct conjugations. This article covers the formation of all types of aorist, with special attention on the athematic second aorist conjugation which few verbs take, but several of them happen to be common. Not Two, but Three Aorists The forms of Greek aorist are usually divided into two classes, the first and the second. The first aorist is pretty simple, but the second aorist actually holds two distinct systems of morphology. I want to point out that the difference between first and second aorists is only a difference in conjugation. The meanings and uses of all these aorists are the same, but I’m not going to cover that here. See Goodwin’s Syntax of the Moods and Tenses of the Greek Verb, or your favorite Greek grammar, for more about aorist syntax. In my verb charts I give the indicative active forms, indicate nu-movable with ”(ν)”, and al- ways include the dual forms. Beginners can probably skip the duals unless they are starting with Homer. The First Aorist This is taught as the regular form of the aorist. Like the future, a sigma is tacked onto the stem, so it sometimes called the sigmatic aorist. It is sometimes also called the weak aorist. Since it acts as a secondary (past) tense in the indicative, it has an augment: ἐ + λυ + σ- Onto this we tack on the endings. -

Adverbs in Kenyang

International Journal of Linguistics and Communication June 2015, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 112-133 ISSN: 2372-479X (Print) 2372-4803 (Online) Copyright © The Author(s). All Rights Reserved. Published by American Research Institute for Policy Development DOI: 10.15640/ijlc.v3n1a13 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.15640/ijlc.v3n1a13 Adverbs in Kenyang Tabe Florence A. E1 Abstract Kenyang (a Niger-Congo language spoken in Cameroon) has both pure and derived adverbs. Characteristic features of Kenyang adverbs can be captured from event structure constituting different functional projections in the syntax. Thus the behaviour of adverbs in this language is inextricably bound to both syntactic and semantic phenomena. The nature of the interface between them is explained based on their distribution and properties in the language. The adverbs can appear left-adjoined or right-adjoined to the verb. From a cartographic perspective, Kenyang adverbs can occupy different functional heads comprising the CP, IP and VP respectively. Each syntactic position affects the semantics of the proposition. The possibility of adverb stacking is constrained by the pragmatics of the semantic zones and the co-occurrence and ordering restrictions in the syntax. The ordering is a relative linear proximity rather than a fixed order. The theoretical relevance of the analysis is obtained from the assumption that there is a feasible correlation between the classes of adverbs and independently motivated functional projections, on the one hand, and on the existence of a one-to-one correlation between syntactic positions and semantic structures, on the other hand. Keywords: event structure, adverb taxonomy, interface, adverb focus, adverb ordering 1.0 Introduction Adverbs have been treated as the least homogenous category to define in language because their analysis as a grammatical category remains peripheral to the basic argument structure of the sentence. -

Defective Causative and Perception Verb Constructions in Romance. a Minimalist Approach to Infinitival and Subjunctive Clauses

Defective causative and perception verb constructions in Romance. A minimalist approach to infinitival and subjunctive clauses Elena Ciutescu Doctoral Dissertation Supervised by Dr. Jaume Mateu Fontanals Programa de Doctorat Ciència Cognitiva i Llenguatge Centre de Lingüística Teòrica Departament de Filologia Catalana Facultat de Filosofia i Lletres Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona 2018 Eu nu strivesc corola de minuni a lumii şi nu ucid cu mintea tainele, ce le-ntâlnesc în calea mea în flori, în ochi, pe buze ori morminte. Lumina altora sugrumă vraja nepătrunsului ascuns în adâncimi de întuneric, dar eu, eu cu lumina mea sporesc a lumii taină- şi-ntocmai cum cu razele ei albe luna nu micşorează, ci tremurătoare măreşte şi mai tare taina nopţii, aşa îmbogăţesc şi eu întunecata zare cu largi fiori de sfânt mister şi tot ce-i nenţeles se schimbă-n nenţelesuri şi mai mari sub ochii mei- căci eu iubesc şi flori şi ochi şi buze şi morminte. Lucian Blaga – ‘Eu nu strivesc corola de minuni a lumii’ (Poemele luminii, 1919) Abstract The present dissertation explores aspects of the micro-parametric variation found in defective complements of causative and perception verbs in Romance. The study deals with infinitival and subjunctive clauses with overt lexical subjects in three Romance languages: Spanish, Catalan and Romanian. I focus on various syntactic phenomena of the Case-agreement system in environments that exhibit defective C-T dependencies (in the spirit of Chomsky 2000; 2001, Gallego 2009; 2010; 2014). I argue in favour of a unifying account of the non- finite complementation of causative and perception verbs, investigating at the same time the mechanisms responsible for the micro-parametric variation exhibited by the three languages. -

2008Impersonalization.Pdf

TRPS 211 Dispatch: 24.6.08 Journal: TRPS CE: Blackwell Journal Name Manuscript No. -B Author Received: No. of pages: 23 PE: Mahendrakumar Transactions of the Philological Society Volume 106:2 (2008) 1–23 1 2 INTRODUCTION: IMPERSONALIZATION FROM A 3 SUBJECT-CENTRED VS. AGENT-CENTRED 4 PERSPECTIVE 5 6 By ANNA SIEWIERSKA 7 Lancaster University 8 9 10 1. PRELIMINARIES 11 The notion of impersonality is a broad and disparate one. In the 12 main, impersonality has been studied in the context of Indo- 13 European languages and especially Indo-European diachronic 14 linguistics (see e.g. Seefranz-Montag 1984; Lambert 1998; Bauer 15 2000). It is only very recently that discussions of impersonal 16 constructions have been extended to languages outside Europe (see 17 e.g. Aikhenvald et al. 2001; Creissels 2007; Malchukov 2008 and the 18 papers in Malchukov & Siewierska forthcoming). The currently 19 available analyses of impersonal constructions within theoretical 20 models of grammar are thus all based on European languages. The 21 richness of impersonal constructions in European languages, has, 22 however, ensured that they be given due attention within any model 23 of grammar with serious aspirations. Consequently, the linguistic 24 literature boasts of many theory-specific analyses of various 25 impersonal constructions. The last years have seen a heightening 26 of interest in impersonality and a series of new analyses of 27 impersonal constructions. The present special issue brings together 28 five of these analyses spanning the formal ⁄ functional-cognitive 29 divide. Three of the papers in this volume, by Divjak and Janda, by 30 Afonso and by Helasvuo and Vilkuna, offer analyses couched 31 within or inspired by different versions of the marriage of 32 Construction Grammar and Cognitive Grammar as developed by 33 Langacker (1991), Goldberg (1995, 2006) and Croft (2001). -

Regular Verbs with Present Tense Past Tense and Past Participle

Regular Verbs With Present Tense Past Tense And Past Participle whenOut-of-the-way Mohammed Riccardo entrapping precede his evaporations.her game so irrationallyGambling andthat inviolableDunc moulds Thayne very unreeveslet-alone. hisSentimental pups beguiles and sidewayswattling inchoately. Albert never ambulating persistently Often the content has lost simple past perfect tense verbs with and regular past participle can i cite an adjective from which started. Many artists livedin New York prior to last year. Why focus on the simple past tense in textbooks and past tense and regular verbs can i shall not emphasizing the. The cookies and british or präteritum in the past tables and trivia that behave in july, with regular verbs past tense and participle can we had livedin the highlighted past tense describes an action that! There are not happened in our partners use and regular verbs past tense with the vowel changes and! In search table below little can see Irregular Verbs along is their forms Base was Tense-ded Past Participle-ded Continuous Tense to Present. Conventions as verbs regular past and present tense participle of. The future perfect tells about an action that will happen at a specific time in the future. How soon will you know your departure time? How can I apply to teach with Wall Street English? She is the explicit reasons for always functions as in tense and reports. Similar to the past perfect tense, the past perfect progressive tense is used to indicate an action that was begun in the past and continued until another time in the past. -

Neural Graphical Models Over Strings for Principal Parts Morphological Paradigm Completion

Neural Graphical Models over Strings for Principal Parts Morphological Paradigm Completion Ryan Cotterell1;2 John Sylak-Glassman2 Christo Kirov2 1Department of Computer Science 2Center for Language and Speech Processing Johns Hopkins University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract Nicolai et al., 2015; Ahlberg et al., 2015; Faruqui et al., 2016) has made tremendous progress on this Many of the world’s languages contain an narrower task, paradigm completion is not only abundance of inflected forms for each lex- broader in scope, but is better solved without priv- eme. A major task in processing such lan- ileging the lemma over other forms. By forcing guages is predicting these inflected forms. string-to-string transformations from one inflected We develop a novel statistical model for form to another to go through the lemma, the trans- the problem, drawing on graphical model- formation problem is often made more complex ing techniques and recent advances in deep than by allowing transformations to happen directly learning. We derive a Metropolis-Hastings or through a different intermediary form. This inter- algorithm to jointly decode the model. Our pretation is inspired by ideas from linguistics and Bayesian network draws inspiration from language pedagogy, namely principal parts mor- principal parts morphological analysis. We phology, which argues that forms in a paradigm are demonstrate improvements on 5 languages. best derived using a set of citation forms rather than a single form (Finkel and Stump, 2007a; Finkel and 1 Introduction Stump, 2007b). Inflectional morphology modifies the form Directed graphical models provide a natural for- of words to convey grammatical distinctions malism for principal parts morphology since a (e.g. -

Berkeley Linguistics Society

PROCEEDINGS OF THE THIRTY-SECOND ANNUAL MEETING OF THE BERKELEY LINGUISTICS SOCIETY February 10-12, 2006 SPECIAL SESSION on THE LANGUAGES AND LINGUISTICS OF OCEANIA Edited by Zhenya Antić Charles B. Chang Clare S. Sandy Maziar Toosarvandani Berkeley Linguistics Society Berkeley, CA, USA Berkeley Linguistics Society University of California, Berkeley Department of Linguistics 1203 Dwinelle Hall Berkeley, CA 94720-2650 USA All papers copyright © 2012 by the Berkeley Linguistics Society, Inc. All rights reserved. ISSN 0363-2946 LCCN 76-640143 Printed by Sheridan Books 100 N. Staebler Road Ann Arbor, MI 48103 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS A note regarding the contents of this volume ........................................................ iii Foreword ................................................................................................................ iv SPECIAL SESSION Oceania, the Pacific Rim, and the Theory of Linguistic Areas ...............................3 BALTHASAR BICKEL and JOHANNA NICHOLS Australian Complex Predicates ..............................................................................17 CLAIRE BOWERN Composite Tone in Mian Noun-Noun Compounds ...............................................35 SEBASTIAN FEDDEN Reconciling meng- and NP Movement in Indonesian ...........................................47 CATHERINE R. FORTIN The Role of Animacy in Teiwa and Abui (Papuan) ..............................................59 MARIAN KLAMER AND FRANTIŠEK KRATOCHVÍL A Feature Geometry of the Tongan Possessive Paradigm .....................................71 -

Simple And-Relative Clauses in Panare Spike Gildea A

ii SIMPLE AND-RELATIVE CLAUSES IN PANARE APPROVED: by SPIKE GILDEA A THESIS Presented to the Department of Linguistics and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 1989 iii iv An Abstract of the Thesis of Spike Gildea for the degree of Master of Arts in the Department of Linguistics to be takaa 1989 Title: SIMPLE AND RELATIVE CLAUSES IN PANARE Approved: Copyright 1989 Spike Gildea This thesis is a description, based on original field work, of simple and relative clauses in Panare, a Cariban language spoken by 2000-2500 people in central Venezuela. The three types of simple clauses described are past tenses, predicate nominals, and an aspect- inflected verb with an auxiliary. The set of aspect inflections in Panare is historically derived from a set of nominalizing suffixes, and in related languages, cognates to the Panare aspect suffixes are still nominalizers. The evolution from nominalizer to aspect in Panare follows a previously described pattern language of change, one which appears in studies of both language acquisition and of historical change. The two types of relative clause strategy described are finite, based on the past tense verbs and on one the auxiliaries for the aspect- inflected verb, and the less finite, based on the aspect-inflected verb itself. VITA NAME OF AUTHOR: Spike Lawrence Owen Gildea PLACE OF BIRTH: Salem, Oregon DATE OF BIRTH: June 17, 1961 GRADUATE AND UNDERGRADUATE SGHOOLS ATTENDED: University of Oregon Washington University