Studies in Latin American Ethnohistory & Archaeology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Apus De Los Cuatro Suyos

! " " !# "$ ! %&' ()* ) "# + , - .//0 María Cleofé que es sangre, tierra y lenguaje. Silvia, Rodolfo, Hamilton Ernesto y Livia Rosa. A ÍNDICE Pág. Sumario 5 Introducción 7 I. PLANTEAMIENTO Y DISEÑO METODOLÓGICO 13 1.1 Aproximación al estado del arte 1.2 Planteamiento del problema 1.3 Propuesta metodológica para un nuevo acercamiento y análisis II. UN MODELO EXPLICATIVO SOBRE LA COSMOVISIÓN ANDINA 29 2.1 El ritmo cósmico o los ritmos de la naturaleza 2.2 La configuración del cosmos 2.3 El dominio del espacio 2.4 El ciclo productivo y el calendario festivo en los Andes 2.5 Los dioses montaña: intermediarios andinos III. LAS IDENTIDADES EN LOS MITOS DE APU AWSANGATE 57 3.1 Al pie del Awsangate 3.2 Awsangate refugio de wakas 3.3 De Awsangate a Qhoropuna: De los apus de origen al mundo de los muertos IV. PITUSIRAY Y EL TINKU SEXUAL: UNA CONJUNCIÓN SIMBÓLICA CON EL MUNDO DE LOS MUERTOS 93 4.1 El mito de las wakas Sawasiray y Pitusiray 4.2 El mito de Aqoytapia y Chukillanto 4.3 Los distintos modelos de la relación Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.4 Pitusiray/ Chukillanto y los rituales del agua 4.5 Las relaciones urko-uma en el ciclo de Sawasiray-Pitusiray 4.6 Una homologación con el mito de Los Hermanos Ayar Anexos: El pastor Aqoytapia y la ñusta Chukillanto según Murúa El festival contemporáneo del Unu Urco o Unu Horqoy V. EL PODEROSO MALLMANYA DE LOS YANAWARAS Y QOTANIRAS 143 5.1 En los dominios de Mallmanya 5.2 Los atributos de Apu Mallmanya 5.3 Rivales y enemigos 5.4 Redes de solidaridad y alianzas VI. -

The Political Ecology of Late South American Pastoralism: an Andean Perspective A.D

The political ecology of late South American pastoralism: an Andean perspective A.D. 1,000-1,615 Jennifer Granta1 Kevin Laneb a Instituto Nacional de Antropología y Pensamiento Latinoamericano, Argentina b Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina Abstract Prehispanic South American pastoralism has a long and rich, though often understudied, trajectory. In this paper, we analyze the transition from a generalized to a specialized pastoralism at two geographical locations in the Andes: Antofagasta de la Sierra, Southern Argentina Puna, and the Ancash Highlands, Peruvian North- central Puna. Although at opposite ends of the Andes this herding specialization commences during the same moment in time, A.D. 600-1,000, suggesting that a similar process was at work in both areas. Moreover, this was a process that was irrevocably tied to the coeval development of specialized highland agriculture. From a perspective of political ecology and structuration theory we emphasis the time-depth and importance that Andean pastoralism had in shaping highland landscapes. Taking into consideration risk-management theory, ecology and environment as crucial factors in the development of a specialized pastoralism we nevertheless emphasis the importance of the underlying human decisions that drove this process. Based broadly within the field of political ecology we therefore emphasize how human agency and structure impacted on these landscapes, society and animal husbandry. Our article covers such aspects as the human and animal use of resource areas, settlement location, herding patterns, selective breeding, and human-induced alterations to pasturage. Keywords: Andes, pastoralism, political ecology, Southern Andes, Central Andes Résumé Le pastoralisme préhispanique sud-américain a une trajectoire longue et riche, mais souvent peu étudiée. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

Pscde3 - the Four Sides of the Inca Empire

CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. Manco Cápac 515 – Wanchaq Ca. M. M. Izaga 740 Of. 207 - Chiclayo www.chaskiventura.com T: 51+ 84 233952 T: 51 +74 221282 PSCDE3 - THE FOUR SIDES OF THE INCA EMPIRE SUMMARY DURATION AND SEASON 15 Days/ 14 Nights LOCATION Department of Arequipa, Puno, Cusco, Raqchi community ATRACTIONS Tourism: Archaeological, Ethno tourism, Gastronomic and landscapes. ATRACTIVOS Archaeological and Historical complexes: Machu Picchu, Tipón, Pisac, Pikillaqta, Ollantaytambo, Moray, Maras, Chinchero, Saqsayhuaman, Catedral, Qoricancha, Cusco city, Inca and pre-Inca archaeological complexes, Temple of Wiracocha, Arequipa and Puno. Living culture: traditional weaving techniques and weaving in the Communities of Chinchero, Sibayo, , Raqchi, Uros Museum: in Lima, Arequipa, Cusco. Natural areas: of Titicaca, highlands, Colca canyon, local fauna and flora. TYPE OF SERVICE Private GUIDE – TOUR LEADER English, French, or Spanish. Its presence is important because it allows to incorporate your journey in the thematic offered, getting closer to the economic, institutional, and historic culture and the ecosystems of the circuit for a better understanding. RESUME This circuit offers to get closer to the Andean culture and to understand its world view, its focus, its technologies, its mixture with the Hispanic culture, and the fact that it remains present in Indigenous Communities today. In this way, by bus, small boat, plane or walking, we will visit Archaeological and Historical Complexes, Communities, Museums & Natural Environments that will enable us to know the heart of the Inca Empire - the last heir of the Andean independent culture and predecessor of the mixed world of nowadays. CUSCO LAMBAYEQUE Email: [email protected] Av. -

Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ Ä Æ

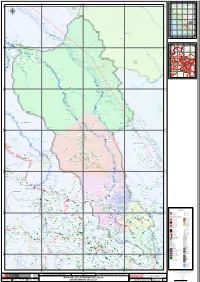

81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W 800000 820000 840000 ° ° 0 0 R 0 í 0 o 0 C 0 COLOMBIA a 0 l 0 l a n 0 0 ECUADOR Victoria g a 2 2 6 Sacramento Santuario 6 8 8 S S 560 Nacional ° ° Esmeralda Megantoni 3 3 TUMBES LORETO PIURA AMAZONAS S S ° ° R 6 LAMBAYEQUECAJAMARCA BRASIL 6 ío 565 M a µ e SAN MARTIN Quellouno st ró Trabajos n LA LIBERTAD Rosario S S Bellavista ° ° 9 ANCASH 9 HUANUCO UCAYALI 570 PASCO R Mesapata 1 ío P CUSCO a u c Monte Cirialo a Ocampo r JUNIN ta S S m CALLAOLIMA ° b ° o MADRE DE DIOS 2 2 1 Rí CUSCO 1 Paimanayoc o M ae strón HUANCAVELICA OCÉANO PACÍFICO Chaupimayo AYACUCHOAPURIMAC 575 ICA PUNO S S Mapitonoa ° ° Chaupichullo Lacco 1 5 5 Qosqopata Quellomayo 1 1 Emp. CU-104. Mameria AREQUIPA Llactapata MOQUEGUA Huaynapata Emp. CU-104. Miraflores MANU Alto Serpiyoc. BOLIVIA S S TACNA Cristo Salvador Achupallayoc ° Emp. CU-698 ° Larco 580 8 8 Emp. CU-104. 1 1 Quesquento Alto. Yanamayo CU Limonpata CU «¬701 81° W 78° W 75° W 72° W 69° W CU Campanayoc Alto Emp. CU-698 Chunchusmayo Ichiminea «¬695 Kcarun 693 Antimayo «¬ Dos De Mayo Santa Rosa Serpiyoc Cerpiyoc Serpiyoc Alto Mision Huaycco Martinesniyoc San Jose de Sirphiyoc Emp. CU-694 (Serpiyoc) CU Emp. CU-696 CU Cosireni Paititi Quimsacocha Emp. CU-105 (Chancamayo) 694 Limonpata Santa C¬ruz 698 Emp. CU-104 585 R « R ¬ « Emp. CU-104 (Lechemayo). í ío CU o U Ur ru ub 697 Emp. -

Suministro Zona Direccion Programasocial Codigofise

Beneficiarios FISE Programas Sociales Suministro Zona Direccion ProgramaSocial CodigoFise 980301010034 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY 1° DE MAYO COMEDOR POPULAR ULLPUHUAYCCO 0301010034 980301010021 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY ASILLO ALTO COMEDOR POPULAR NTRA SRA DEL ROSARIO 0301010021 980301010009 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY ASILLO BAJO COMEDOR POPULAR FLOR DE PISONAY 0301010009 980301010033 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY ASOC SOL BRILLANTE COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN DE GUADALUPE 0301010033 980301010026 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY ATUMPATA ALTA COMEDOR POPULAR SANTA CRUZ DE ATUMPATA 0301010026 980301010048 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY ATUMPATA BAJA COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN DEL ROSARIO 0301010048 980301010019 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY AV ABANCAY 112 COMEDOR PARROQUIAL MIKUNA WASI 0301010019 980301010006 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY AV ABANCAY 112 COMEDOR POPULAR DIVINA PROVIDENCIA 0301010006 980301010031 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY AYMAS COMEDOR POPULAR SANTA TERESITA 0301010031 980301010028 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY BELLA VISTA BAJA ASOC ISIRDOCOMEDOR POPULAR SANTA ISABEL 0301010028 980301010036 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY BELLA VISTA BAJA COMITE V COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN DE ASUNCIÓN 0301010036 980301010041 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY BELLAVISTA ALTA COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN DEL CARMEN 0301010041 980301010004 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY CARCATERA COMEDOR POPULAR SANTA ROSA 0301010004 980301010052 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY CATEDRALTRUJIPATA COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN ROSARIO 0301010052 980301010039 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY CCACSA COMEDOR POPULAR VIRGEN DE FÁTIMA 0301010039 980301010012 APURIMAC/ABANCAY/ABANCAY -

How Did the Inka Apply Innovation to Water Management?

Teacher Materials The Importance of Water Management: How did the Inka apply innovation to water management? Lesson Components The Power of Water: Urubamba River Image Description Urubamba River Video: Witness the sheer power of this river in the Andes. Consider how we depend on water and the extent to which we can control its force. AmericanIndian.si.edu/NK360 1 The Inka Empire: The Inka Empire What innovations can provide food and water for millions? Teacher Materials The Importance of Water Management Explore Inka Water Management Image Description 360-degree Panoramic: Explore the Inka ancestral site of Pisac showing erosion and terracing. Preventing Erosion Video: See how the Inka prevented erosion by controlling the destructive force of water. Engineer an Inka Terrace: Put your engineering skills to the test. Place materials in the correct order to create a stable terrace. Tipón Video and Water Management Interactive: Discover how water was distributed to irrigate agricultural terraces and supply water to the local population. AmericanIndian.si.edu/NK360 2 The Inka Empire: The Inka Empire What innovations can provide food and water for millions? Teacher Materials The Importance of Water Management Contemporary Connections: Inka Water Management Today Image Description Drinking from an Inka Fountain Video: See how water is still available for drinking in Machu Picchu. Interviews with Local Experts: Read interviews with local experts from the Sacred Valley in the Cusco Region of Peru who still use water management methods introduced by the Inka. Student Worksheet Inka Water Management Connection to the Compelling Question In this lesson, students will construct their own understanding of water management by investigating several innovative engineering techniques used by the Inka Empire. -

Brazil Eyes the Peruvian Amazon

Site of the proposed Inambari Dam in the Peruvian Amazon. Brazil Eyes the Photo: Nathan Lujan Peruvian Amazon WILD RIVERS AND INDIGENOUS PEOPLES AT RISK he Peruvian Amazon is a treasure trove of biodiversity. Its aquatic ecosystems sustain Tbountiful fisheries, diverse wildlife, and the livelihoods of tens of thousands of people. White-water rivers flowing from the Andes provide rich sediments and nutrients to the Amazon mainstream. But this naturally wealthy landscape faces an ominous threat. Brazil’s emergence as a regional powerhouse has been accom- BRAZIL’S ROLE IN PERU’S AMAZON DAMS panied by an expansionist energy policy and it is looking to its In June 2010, the Brazilian and Peruvian governments signed neighbors to help fuel its growth. The Brazilian government an energy agreement that opens the door for Brazilian com- plans to build more than 60 dams in the Brazilian, Peruvian panies to build a series of large dams in the Peruvian Amazon. and Bolivian Amazon over the next two decades. These dams The energy produced is largely intended for export to Brazil. would destroy huge areas of rainforest through direct flood- The first five dams – Inambari, Pakitzapango, Tambo 40, ing and by opening up remote forest areas to logging, cattle Tambo 60 and Mainique – would cost around US$16 billion, ranching, mining, land speculation, poaching and planta- and financing is anticipated to come from the Brazilian National tions. Many of the planned dams will infringe on national Development Bank (BNDES). parks, wildlife sanctuaries and some of the largest remaining wilderness areas in the Amazon Basin. -

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Pollen Dispersal and Deposition in the High-Central Andes, South America Carl A. Reese

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2003 Pollen dispersal and deposition in the high-central Andes, South America Carl A. Reese Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Reese, Carl A., "Pollen dispersal and deposition in the high-central Andes, South America" (2003). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1690. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1690 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. POLLEN DISPERSAL AND DEPOSITION IN THE HIGH-CENTRAL ANDES, SOUTH AMERICA A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography and Anthropology by Carl A. Reese B.A., Louisiana State University, 1998 M.S., Louisiana State University, 2000 August 2003 Once again, To Bull and Sue ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost I would like to thank my major professor, Dr. Kam-biu Liu, for his undying support throughout my academic career. From sparking my initial interest in the science of biogeography, he has wisely led me through swamps and hurricanes, from the Amazon to the Atacama, and from sea level to the roof of the world with both patience and grace. -

INCA TRAIL to MACHU PICCHU RUNNING ADVENTURE July 31 to August 8, 2021 OR July 31 to August 9, 2021 (With Rainbow Mountain Extension)

3106 Voltaire Dr • Topanga, CA 90290 PHONE (310) 395-5265 e-mail: [email protected] www.andesadventures.com INCA TRAIL TO MACHU PICCHU RUNNING ADVENTURE July 31 to August 8, 2021 OR July 31 to August 9, 2021 (with Rainbow Mountain extension) Day 1 Saturday — July 31, 2021: Lima/Cusco Early morning arrival at the Lima airport, where you will be met by an Andes Adventures representative, who will assist you with connecting flights to Cusco. Depart on a one-hour flight to Cusco, the ancient capital of the Inca Empire and the continent's oldest continuously inhabited city. Upon arrival in Cusco, we transfer to the hotel where a traditional welcome cup of coca leaf tea is served to help with the acclimatization to the 11,150 feet altitude. After a welcome lunch we will have a guided sightseeing tour of the city, visiting the Cathedral, Qorikancha, the most important temple of the Inca Empire and the Santo Domingo Monastery. You will receive a tourist ticket valid for the length of the trip enabling you to visit the many archaeological sites, temples and other places of interest. After lunch enjoy shopping and sightseeing in beautiful Cusco. Dinner and overnight in Cusco. Overnight: Costa del Sol Ramada Cusco (Previously Picoaga Hotel). Meals: L, D. Today's run: None scheduled. Day 2 Sunday — August 1, 2021: Cusco Morning visit to the archaeological sites surrounding Cusco, beginning with the fortress and temple of Sacsayhuaman, perched on a hillside overlooking Cusco at 12,136 feet. It is still a mystery how this fortress was constructed. -

Cusco Y Su Montaña Sagrada

CUSCO Y SU MONTAÑA SAGRADA Teléfono. +51 84 224 613 | Celular. +51 948 315 330 Desde EE.UU. +1 646 844 7431 Av. Brasil A-14, Urb. Quispicanchi, Cusco, Perú [email protected] | www.andeanlodges.com DÍA 1: LLEGADA Y CITY TOUR A su llegada al aeropuerto de Cusco, un miembro de nuestro equipo lo estará esperando para darle la bienvenida, y acompañarlo hasta su hotel. Por la tarde, uno de nuestros guías pasará por su hotel, para iniciar el primer tour en la ciudad, comenzando en Sacsayhuaman. Éste es uno de los más imponentes sitios arqueológicos en el área, debido a sus estructuras megalíticas. Luego, continuaremos por la Plaza de Armas, y la Catedral del Cusco, la cual cuenta con más de 300 pinturas de la Escuela Cusqueña de Arte, decorando sus históricas paredes de piedra. Nuestra última parada del día será en el centro del Imperio Incaico, conocido como el Templo de Oro, o por su nombre en quechua, Qoricancha. Este impresionante título, se refiere a los días en el incanato, cuando las paredes de esta inmortal estructura estaban cubiertas por planchas de oro. Sin embargo, cuando los españoles llegaron, la inimaginable cantidad de oro fue derretida y convertida en “Escudos” (la moneda de España de ese tiempo), para ser llevada de vuelta a España. Y sobre este templo se construyó el Convento y la iglesia de Santo Domingo, una impresionante construcción de estilo barroco, que nos recuerda la imposición de dominio por parte de los europeos en ese tiempo. PERNOCTE: Cusco Teléfono. +51 84 224 613 | Celular. -

Machu Picchu & Abra Malaga, Peru II 2018 BIRDS

Field Guides Tour Report Machu Picchu & Abra Malaga, Peru II 2018 Oct 5, 2018 to Oct 14, 2018 Jesse Fagan For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. Our hike to the ridge above Abra Malaga couldn't have been more magical. Cerro Veronica in the background and feeding alpaca in the foreground, that is the Andes in Peru. Video grab by guide Jesse Fagan. I hope that you found Peru to be overwhelmingly beautiful. The food, the people, the Andes, the humid forest, Machu Picchu, and, of course, the birds. Indeed, this is my second home, and so I hope you felt welcomed here and decide to return soon. Peru is big (really big!) and there is much, much more to see. The birding was very good and a few highlights stood out for everyone. These included Andean Motmot, Pearled Treerunner, Plumbeous Rail, Versicolored Barbet, and Spectacled Redstart. However, a majority of the group thought seeing Andean Condors, well, in the Andes (!) was pretty darn cool. Black-faced Ibis feeding in plowed fields against Huaypo lake was a memory for a few others. I was glad to see one of my favorite birds stood out, the shocking Bearded Mountaineer (plus, maybe I am just partial to the "bearded" part). But you couldn't beat Andean Cock-of-the-Rock for shock value and the female on a nest was something you don't see everyday. Thanks to our team of drivers, and Lucrecia, our informative and always pleasant local guide. I hope to see you again soon.