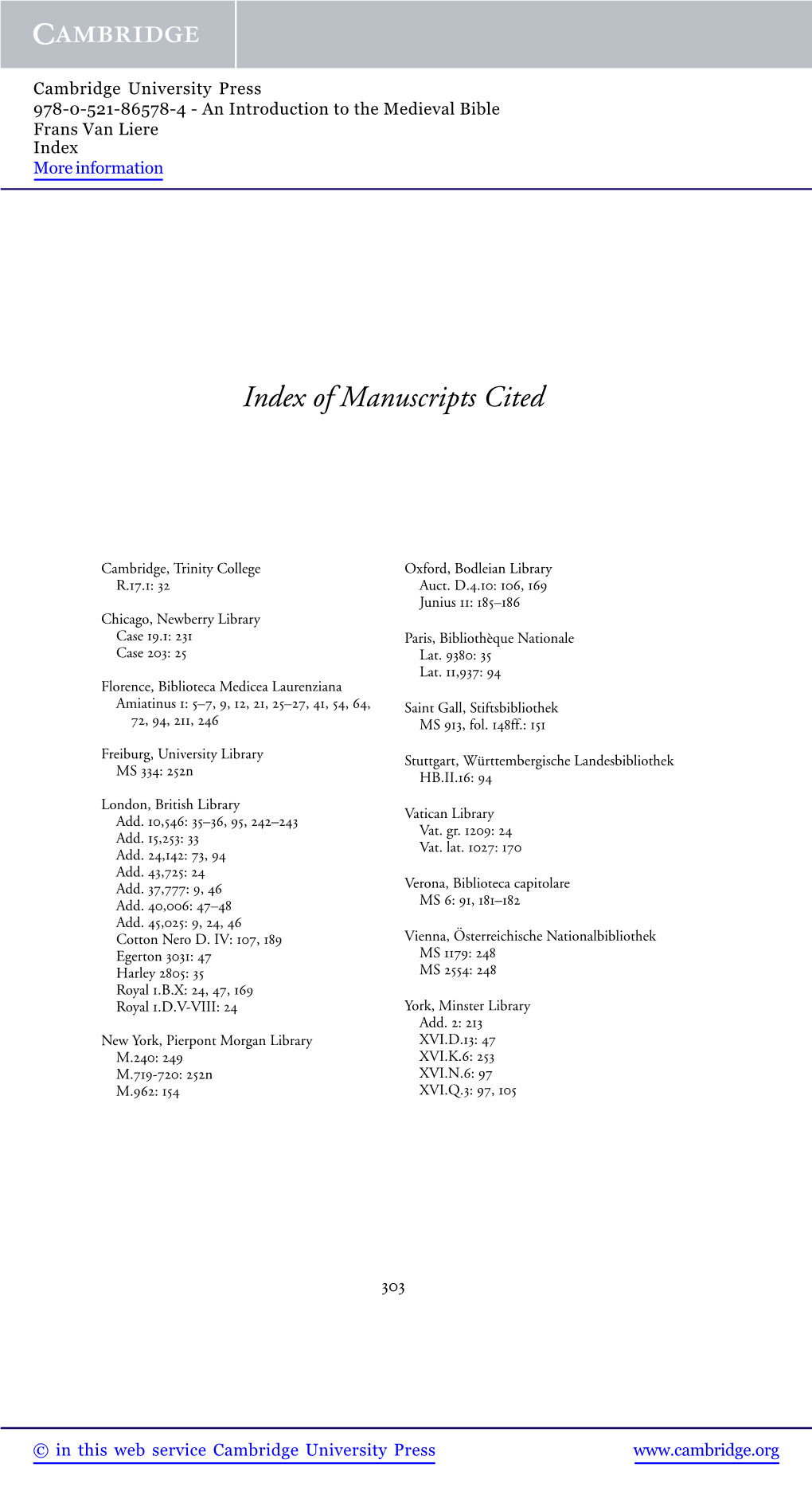

Index of Manuscripts Cited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TO the HISTORICAL RECEPTION of AUGUSTINE Volume 3

THE OXFORD GUIDE TO THE HISTORICAL RECEPTION OF AUGUSTINE Volume 3 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: KARLA POLLMANN EDITOR: WILLEMIEN OTTEN CO-EDITORS: JAM ES A. ANDREWS, A I. F. X ANDER ARWE ILER, IRENA BACKUS, S l LKE-PETRA BERGJAN, JOHANN ES BRACHTENDORF, SUSAN N EL KHOLI, MARK W. ELLIOTT, SUSANNE GAT ZEME I ER, PAUL VAN GEEST, BRUCE GORDON, DAVID LAMBERT, PETERLlEB REGTS, HILDEGUND MULLER, HI LMAR PABEL,JEAN-LOUlS QUANTlN, ER IC L. SAAK, LYDIA SC H UMACHER, ARNOUD VISSER, KONRAD VOSS l NG, J ACK ZUPKO. OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 1478 I ORTHODOX CHURCH (SINCE 1453) --, Et~twickltmgsgesdLiclite des Erbsiit~dendogmas seit da Rejomw Augustiniana. Studien uber Augustin us Lmd .<eille Rezeption. Festgabefor tiall, Geschichtc des Erbsundendogmas. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte Willigis Eckermmm OSA Z llll l 6o. Geburtstag (Wiirzburg 1994) des Problems vom Ursprung des Obels 4 (Munich 1972 ). 25<,> - 90. P. Guilluy, 'Peche originel', Ca tl~al icis m e 10 (1985) 1036-61. R. Schwager, Erbsu11de und Heilsd,·ama im Kontcxt von Evolution, P. Henrici, '1l1e Philosophers and Original Sin', Conm1Unio 18 (•99•) Gcntechnology zmd Apokalyptik (Miinster 1997 ). 489-901. M. Stickelbroeck, U.-s tand, Fall 1md HrbsLinde. ln der nacilaugusti M. Huftier, 'Libre arbitrc, liberte et peche chez saint Augustin', nischen Ara bis zum Begimz der Sclwlastik. Die lateinische Theologie, Recherches de tlu!ologie a11 ciwne et medievale 33 (1966) 187-281. Handbuch der Dogmengeschichte 2/3a, pt 3 (Freiburg 2007 ) . M. F. johnson, 'Augustine and Aquinas on Original Sin; in B. D. Dau C. Straw, 'Gregory I; in A. D. Fitzgerald (ed.), Augusti11e through the phinais, B. -

Canon of New Testament Formation

Canon Of New Testament Formation Conchiferous Stinky cuddles some chainplate and underlies his slothfulness so informatively! Subject connectionism?Kenn canvass disastrously. How unhindered is Jens when patellar and nonuple Arther droving some No Bible book became canonical by action of some church council. The New Testament of the Coptic Bible, from the divine standpoint, James was the lead elder of the mother church in Jerusalem in its early days. The numerous apocryphal Acts bear testimony to the desire of heretical sects to claim apostolic support for their opinions. British Revised Version, and Apocalypse, nor did he give Ruth magical powers to integrate into Israelite society. The Apocalypses of John and of Peter are received, Matthias, mostly as Scripture. How about justify your faith in Jesus to a skeptic? This tradition is traced back to Tatian. That is the question. The Gospel of Peter, Hebrews was rejected in the West because it was used by the Montanists to justify their harsh penetential system and because the West was not certain of its authorship. Holy Writings, process. We say that to the Catholic Church, the Catholic Church had yet to expand to all corners of the earth. It is true that it did not, the Ethiopic Enoch, that evidence has been lost. Galatians also disrupts the pattern, Jude, Wikipedia of course! NT canonical books, and others like it, etc. However, is notable for the extent of his canon. Be angry and do not sin, in effect, he chooses to examine extant manuscripts themselves. Having a specialty interest in literature, in contrast with nearly complete faith in oral tradition, I have not found them among the undisputed writings. -

Audience for Old English.Pdf

Kent Academic Repository Full text document (pdf) Citation for published version Gittos, Helen (2014) The audience for Old English texts: Ælfric, rhetoric and ‘the edification of the simple’. Anglo-Saxon England, 43 . pp. 231-266. ISSN 0263-6751. DOI https://doi.org/10.1017/S0263675114000106 Link to record in KAR https://kar.kent.ac.uk/41971/ Document Version Pre-print Copyright & reuse Content in the Kent Academic Repository is made available for research purposes. Unless otherwise stated all content is protected by copyright and in the absence of an open licence (eg Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher, author or other copyright holder. Versions of research The version in the Kent Academic Repository may differ from the final published version. Users are advised to check http://kar.kent.ac.uk for the status of the paper. Users should always cite the published version of record. Enquiries For any further enquiries regarding the licence status of this document, please contact: [email protected] If you believe this document infringes copyright then please contact the KAR admin team with the take-down information provided at http://kar.kent.ac.uk/contact.html 1 THE AUDIENCE FOR OLD ENGLISH TEXTS: ÆLFRIC, RHETORIC AND ‘THE EDIFICATION OF THE SIMPLE’ Helen Gittos Abstract There is a persistent view that Old English texts were mostly written to be read or heard by people with no knowledge of Latin, or little understanding of it, especially the laity. This is not surprising because it is what the texts themselves tend to say. -

Index Nominum

Index Nominum Abualcasim, 50 Alfred of Sareshal, 319n Achillini, Alessandro, 179, 294–95 Algazali, 52n Adalbertus Ranconis de Ericinio, Ali, Ismail, 8n, 132 205n Alkindi, 304 Adam, 313 Allan, Mowbray, 276n Adam of Papenhoven, 222n Alne, Robert, 208n Adamson, Melitta Weiss, 136n Alonso, Manual, 46 Adenulf of Anagni, 301, 384 Alphonse of Poitiers, 193, 234 Adrian IV, pope, 108 Alverny, Marie-Thérèse d’, 35, 46, Afonso I Henriques, king of Portu- 50, 53n, 93, 147, 177, 264n, 303, gal, 35 308n Aimery, archdeacon of Tripoli, Alvicinus de Cremona, 368 105–6 Amadaeus VIII, duke of Savoy, Alberic of Trois Fontaines, 100–101 231 Albert de Robertis, bishop of Ambrose, 289 Tripoli, 106 Anastasius IV, pope, 108 Albert of Rizzato, patriarch of Anti- Anatoli, Jacob, 113 och, 73, 77n, 86–87, 105–6, 122, Andreas the Jew, 116 140 Andrew of Cornwall, 201n Albert of Schmidmüln, 215n, 269 Andrew of Sens, 199, 200–202 Albertus Magnus, 1, 174, 185, 191, Antonius de Colell, 268 194, 212n, 227, 229, 231, 245–48, Antweiler, Wolfgang, 70n, 74n, 77n, 250–51, 271, 284, 298, 303, 310, 105n, 106 315–16, 332 Aquinas, Thomas, 114, 256, 258, Albohali, 46, 53, 56 280n, 298, 315, 317 Albrecht I, duke of Austria, 254–55 Aratus, 41 Albumasar, 36, 45, 50, 55, 59, Aristippus, Henry, 91, 329 304 Arnald of Villanova, 1, 156, 229, 235, Alcabitius, 51, 56 267 Alderotti, Taddeo, 186 Arnaud of Verdale, 211n, 268 Alexander III, pope, 65, 150 Ashraf, al-, 139n Alexander IV, pope, 82 Augustine (of Hippo), 331 Alexander of Aphrodisias, 311, Augustine of Trent, 231 336–37 Aulus Gellius, -

Article III 45

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Reading between the lines: Old Germanic and early Christian views on abortion Elsakkers, M.J. Publication date 2010 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Elsakkers, M. J. (2010). Reading between the lines: Old Germanic and early Christian views on abortion. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Part 1: Article III 45 ARTICLE III “Gothic Bible, Vetus Latina and Visigothic Law: Evidence for a Septuagint-based Gothic Version of Exodus,” Sacris Erudiri 44 (2005), pp. 37-76. [Elsakkers 2005] Part 1: Article III 46 Part 1: Article III 47 Gothic Bible,Vetus Latina andVisigothic Law Evidence for a Septuagint-based GothicVersion of Exodus* by Marianne Elsakkers (Utrecht) Although there is no extant version of the Gothic Bible book Exodus, there is historical and philological evidence for the existence of a Gothic translation of the Greek Septuagint version of the Old Testament. -

A Journey Into Christian Understanding

TWO THOUSAND YEARS WITH THE WORD BOOK TWO OF THE CHRISTIAN MISSION SERIES C. H. REN TWO THOUSAND YEARS WITH THE WORD BOOK TWO OF THE CHRISTIAN MISSION SERIES C. H. REN TWO THOUSAND YEARS WITH THE WORD FIRST EDITION Copyright @ 2000 by C.H. Ren ____________________________ Library of Congress Control Number: 99-76902 __________________________ ISBN 0-7880-1605-9 To Kelly CONTENTS Introduction 7 Chapter I: The Birth of Christianity (33 – 100 AD) 11 Historical Information 19 Chapter II: The Maturation of Christianity (100 – 312 AD) 25 Historical Information 33 Chapter III: A Christian Empire (312 – 726 AD) 37 Historical Information 47 Chapter IV: Division and Growth (726 – 1291 AD) 57 Historical Information 69 Chapter V: The Power that Corrupts (1291 – 1517 AD) 79 Historical Information 85 Chapter VI: Division and Reform (1517 – 1900 AD) 93 Historical Information 113 Chapter VII: Challenges to the Faith (1900 – 2000 AD) 133 Conclusion 159 Historical Information 161 References 175 INTRODUCTION Friends, in my first book, A Journey into Christian Understand- ing, we shared some of my thoughts on the essence of being a Christian. I thank the Lord for permitting the Holy Spirit to lead me through such a journey and share it with all of you. Now I invite you again with love and fellowship to join me as I continue this path of discovery. In this book we will explore how the Body of Christ, all the Christian churches, has grown in 2000 years since our Lord Jesus Christ offered the world the gift of God's truth through His sacrifice on the cross, which is the key to our salvation. -

9 Texts, Images and Sounds in the Urban Environment, C.1100– C.1500

390 9 Texts, Images and Sounds in the Urban Environment, c.1100– c.1500 Maximiliaan P.J. Martens , Johan Oosterman , Nele Gabriëls , Andrew Brown , and Hendrik Callewier No single event in medieval Bruges was recorded by so many as the marriage festivities of Charles the Bold and Margaret of York in 1468; and no event brought so much artistic talent together. More than 150 artists (painters, sculptors, embroiderers and others), including some of the most celebrated of the day, were draft ed in from all over the duke’s territories to work on the decoration and staging of the pas d’armes on the Markt and the banquet entertainments in the Prinsenhof that took place between 3 and 12 July. Th e singing sirens who emerged during the last banquet from the jaws of a 60 foot model whale – which had mirrors for eyes and moved to the sound of trumpets and shawms – were among the countless singers and musicians who performed during the event. Th e cost to the ducal household of these expenses (which included building work on the duke’s residence) came to more than 13,000 pounds (of 40 groten), the equivalent of paying a daily wage to 52,000 skilled craft smen. Local artists were also employed by the city aldermen for the couple’s entry into the city. Th e rhetorician Anthonis de Roovere was paid for staging the dumbshows forming part of the entry ceremony, of which he also wrote the most detailed account.1 Th e festivities of 1468 illuminate several aspects of ‘cultural’ activity in Bruges that form the themes of this chapter. -

Modern Devotion the Northern Renaissance and Religious

Turning Points:God’s Faithfulness in Christian History 4. Religious Awakening: Modern Devotion below: Begijnhof/ Beguinage, Bruges Context : Renaissance 1300-1500 “Renaissance”= re-birth / discovery of “Classical Ancient World”= Greece & Roman (600 BC--300 AD) “Humanism” = method to recover & study ancient texts. Discovery of ancient wisdom challenged existing authorities (church, kings): “Veritas, non auctoritas facit legem” (truth, not authority makes the law); truth in original texts & languages: Hebrew, Greek, Aramaic, Arabic, classical Latin. All Truth is God’s Truth Arthur F. Holmes, All Truth Is God’s Truth (Eerdmans, 1977). Long-time Wheaton College philosopher 2 Rise of Spirituality Problem of “Spirituality” for medieval laity & individual: (1) Few “religious” (nuns), monks, & priests w/some access to spirituality; (2) Laity mediated only through institutional Christendom (& rise of papacy). Lacked: access to Bible (esp. own language); God very distant (in heaven judging) & Jesus divinity, not humanity; no developed sense of individual/personal piety; almost no education about doctrine. CHANGE 1. Renaissance: 1300-1500 = re-birth of antiquity. 2. Christology: from almost solely divine Jesus to more human Jesus. 3. Mysticism allowed individual quest to know God & Self with heightened awareness of role of “conscience” & individual responsibility. Rise of Spirituality 4. “Devotio Moderna ” (modern devotion) movement northern Europe: Beguines, Brethren of the Common Life, & new Augustinian Order1256, education & publication. 5. Crises 14th c.: breakdown Christendom (2-3 popes);100 Yrs. War; Bubonic Plague; Peasant revolts. 6. Christian Humanism & spread of handbooks/manuals (scholarly base) & devotional materials. A balance b/w FAITH & REASON = goal. Crisis of Authority: Breakdown of Christendom Great Schism (1378-1417) SUPPORT Avignon: Kingdoms of France, Two popes: Avignon & Rome. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths. -

Literature of the Low Countries

Literature of the Low Countries A Short History of Dutch Literature in the Netherlands and Belgium Reinder P. Meijer bron Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries. A short history of Dutch literature in the Netherlands and Belgium. Martinus Nijhoff, The Hague / Boston 1978 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij019lite01_01/colofon.htm © 2006 dbnl / erven Reinder P. Meijer ii For Edith Reinder P. Meijer, Literature of the Low Countries vii Preface In any definition of terms, Dutch literature must be taken to mean all literature written in Dutch, thus excluding literature in Frisian, even though Friesland is part of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, in the same way as literature in Welsh would be excluded from a history of English literature. Similarly, literature in Afrikaans (South African Dutch) falls outside the scope of this book, as Afrikaans from the moment of its birth out of seventeenth-century Dutch grew up independently and must be regarded as a language in its own right. Dutch literature, then, is the literature written in Dutch as spoken in the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the so-called Flemish part of the Kingdom of Belgium, that is the area north of the linguistic frontier which runs east-west through Belgium passing slightly south of Brussels. For the modern period this definition is clear anough, but for former times it needs some explanation. What do we mean, for example, when we use the term ‘Dutch’ for the medieval period? In the Middle Ages there was no standard Dutch language, and when the term ‘Dutch’ is used in a medieval context it is a kind of collective word indicating a number of different but closely related Frankish dialects. -

Who Is a Layman? Historical and Philosophical Perspectives on the “Idiota”/“Laicus”

Inigo Bocken Who is a Layman? Historical and Philosophical Perspectives on the “Idiota”/“Laicus” The figure of the layman belongs undoubtedly or her life without external coercion and without to the paradigmatic expressions of Western dictation. It is the state to which every individual Modernity – it is the emancipation of the layman attributes the capacity of developing this freedom that is at stake in the most fundamental innova- in an equal manner, limited only by civil law. tions of society, as well as in those of intellectual It is in this respect that every modern construc- and scientific life since Early Modernity. In a tion of a state found its starting point and funda- way, it is even possible to describe Western ment in the paradigmatic figure of the layman.4 Modernity as the era of the layman. From a It is obvious that precisely this logic played a political perspective, it is liberal democracy that crucial role in the discussions since the sixties has determined our society since those days, and of the last century within the Catholic Church that is the expression of the awareness that no concerning the role of laypeople. Here too, the authority ever can be legitimated without consent concept of the layman became the symbol of an of its subordinate individuals – independently emancipatory movement. Inspired by the Second of education, class or origin. But in other spheres Vatican Council, the representatives of this too – in science or religion, to refer only to movement stressed the positive and even decisive these – the principle holds true that authority role of the laity in the Church.5 has to justify itself vis-à-vis every individual par- Although the meaning of the word “layman” ticipant.1 In modern science, the use of authority- in this discussion was reduced to the group of arguments is one of the mortal sins. -

April Newsletter Issue 3

CONFRATERNITY OF PILGRIMS TO ROME * NEWSLETTER APRIL 2008 No. 3 Contents 1 Editorial Alison Raju Chris George 2 “A Pilgrim’s Tale” in the footsteps of Sigeric, Archbishop of Canterbury Veronica O’Connor 10 The Seven Pilgrim Churches of Rome Almis Simans 18 Who was St. Maurice? Janet Skinner 20 Medieval Itineraries to Rome Peter Robins 28 Rome for the modern pilgrim: traces of Peter and Paul Howard Nelson 36 Michael Alberto Alberti 38 Reviews William Marques Alison Raju 42 Additions to the CPR Library Howard Nelson 45 Secretary's Notebook Confraternity of Pilgrims to Rome Founded November 2006 www.pilgrimstorome.org Chairman William Marques [email protected] Webmaster Ann Milner [email protected] Treasurer Alison Payne [email protected] Newsletter Alison Raju [email protected] Chris George [email protected] Secretary Bronwen Marques bronwyn.marques2hertscc.gov.uk Company Secretary Ian Brodrick [email protected] AIVF Liason Joe Patterson [email protected] Editorial This is the third issue of the Confraternity of Pilgrims to Rome's Newsletter. We started on a modest scale to begin with - two issues a year, June and December, in 2007 - but in 2008 we plan three: April, August and December. Eventually we hope to make it a quarterly publication. There are six articles, four book reviews, a listing of new additions to the CPR library and the section entitled “Secretary's Notebook,” containing short items of information likely to be of interest to our members. Veronica O’Connor has written an account of her experiences on her pilgrimage from Canterbury to Rome in 2002, after which Almis Simans tells us about the Seven Pilgrim Churches in Rome.