A New Feather Type in a Nonavian Theropod and the Early Evolution of Feathers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chinese Archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx Gen. Nov

A Chinese archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. by Qiang Ji and Shu’an Ji Geological Science and Technology (Di Zhi Ke Ji) Volume 238 1997 pp. 38-41 Translated By Will Downs Bilby Research Center Northern Arizona University January, 2001 Introduction* The discoveries of Confuciusornis (Hou and Zhou, 1995; Hou et al, 1995) and Sinornis (Ji and Ji, 1996) have profoundly stimulated ornithologists’ interest globally in the Beipiao region of western Liaoning Province. They have also regenerated optimism toward solving questions of avian origins. In December 1996, the Chinese Geological Museum collected a primitive bird specimen at Beipiao that is comparable to Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer, 1992). The specimen was excavated from a marl 5.5 m above the sediments that produce Sinornithosaurus and 8-9 m below the sediments that produce Confuciusornis. This is the first documentation of an archaeopterygian outside Germany. As a result, this discovery not only establishes western Liaoning Province as a center of avian origins and evolution, it provides conclusive evidence for the theory that avian evolution occurred in four phases. Specimen description Class Aves Linnaeus, 1758 Subclass Sauriurae Haeckel, 1866 Order Archaeopterygiformes Furbringer, 1888 Family Archaeopterygidae Huxley, 1872 Genus Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. Genus etymology: Acknowledges that the specimen possesses characters more primitive than those of Archaeopteryx. Diagnosis: A primitive archaeopterygian with claviform and unserrated dentition. Sternum is thin and flat, tail is long, and forelimb resembles Archaeopteryx in morphology with three talons, the second of which is enlarged. Ilium is large and elongated, pubes are robust and distally fused, hind limb is long and robust with digit I reduced and dorsally migrated to lie in opposition to digit III and forming a grasping apparatus. -

A New Understanding of the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Western Liaoning

Open Journal of Geology, 2019, 9, 658-660 https://www.scirp.org/journal/ojg ISSN Online: 2161-7589 ISSN Print: 2161-7570 A New Understanding of the Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in Western Liaoning Zijie Wu1,2, Longwei Qiu1, Haipeng Wang2 1School of Geosciences, China University of Petroleum, Qingdao, China 2Liaoning Provincial Institute of Geological Exploration Co., Ltd., Dalian, China How to cite this paper: Wu, Z.J., Qiu, Abstract L.W. and Wang, H.P. (2019) A New Un- derstanding of the Lower Cretaceous Jiufo- The Lower Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation in western Liaoning is the most tang Formation in Western Liaoning. Open important fossil production horizon of the Jehol Biota, which is widely dis- Journal of Geology, 9, 658-660. tributed in the Mesozoic basins of western Liaoning. Due to the influence of https://doi.org/10.4236/ojg.2019.910067 historical data, previous scholars believed that there was no volcanic activity Received: August 16, 2019 in the Jiufotang Formation in western Liaoning. In a field investigation in Accepted: September 21, 2019 western Liaoning, the authors discovered basalt and andesite in the Hu- Published: September 24, 2019 jiayingzi bed. In addition, a conformable boundary was found between the Copyright © 2019 by author(s) and Yixian and the Jiufotang formations. It indicates that both the Jiufotang For- Scientific Research Publishing Inc. mation and the Yixian Formation are strata containing volcanic-sedimentary This work is licensed under the Creative rocks, only differing in strength of volcanic activity. Commons Attribution International License (CC BY 4.0). Keywords http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Open Access Western Liaoning, Lower Cretaceous, Jiufotang Formation, Volcanic Rocks, New Discoveries 1. -

Luis V. Rey & Gondwana Studios

EXHIBITION BY LUIS V. REY & GONDWANA STUDIOS HORNS, SPIKES, QUILLS AND FEATHERS. THE SECRET IS IN THE SKIN! Not long ago, our knowledge of dinosaurs was based almost completely on the assumptions we made from their internal body structure. Bones and possible muscle and tendon attachments were what scientists used mostly for reconstructing their anatomy. The rest, including the colours, were left to the imagination… and needless to say the skins were lizard-like and the colours grey, green and brown prevailed. We are breaking the mould with this Dinosaur runners, massive horned faces and Revolution! tank-like monsters had to live with and defend themselves against the teeth and claws of the Thanks to a vast web of new research, that this Feathery Menace... a menace that sometimes time emphasises also skin and ornaments, we reached gigantic proportions in the shape of are now able to get a glimpse of the true, bizarre Tyrannosaurus… or in the shape of outlandish, and complex nature of the evolution of the massive ornithomimids with gigantic claws Dinosauria. like the newly re-discovered Deinocheirus, reconstructed here for the first time in full. We have always known that the Dinosauria was subdivided in two main groups, according All of them are well represented and mostly to their pelvic structure: Saurischia spectacularly mounted in this exhibition. The and Ornithischia. But they had many things exhibits are backed with close-to-life-sized in common, including structures made of a murals of all the protagonist species, fully special family of fibrous proteins called keratin fleshed and feathered and restored in living and that covered their skin in the form of spikes, breathing colours. -

Zircon U-Pb SHRIMP Dating of the Yixian Formation in Sihetun, Northeast China

Cretaceous Research 28 (2007) 177e182 www.elsevier.com/locate/CretRes New evidence for Cretaceous age of the feathered dinosaurs of Liaoning: zircon U-Pb SHRIMP dating of the Yixian Formation in Sihetun, northeast China Wei Yang a, Shuguang Li a,*, Baoyu Jiang b a Department of Earth and Space Sciences, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei 230026, China b Department of Earth Sciences, Nanjing University, Nanjing 210093, China Accepted 30 May 2006 Available online 25 January 2007 Abstract We present the first report of U-Pb SHRIMP dating of zircons from three tuffs interbedded within the ‘‘feathered dinosaur’’-bearing deposits in western Liaoning, China. One is a sample from the Bed 6 tuff (LX-SHT-12) of the Yixian Formation in Sihetun, for which our zircon U-Pb SHRIMP analyses gave a Cretaceous age (124.7 Æ 2.7 Ma), in agreement with a previously published sanidine 40Ar/39Ar age (124.60 Æ 0.25 Ma). The other two are from the Bed 1 tuff (LX-HBJ-1) and Bed 8 tuff (LX-HBJ-6) of the Yixian Formation in Huangbanjigou; the former gave an age of 124.9 Æ 1.7 Ma, the latter an age of 122.8 Æ 1.6 Ma. The three consistent ages indicate that the Yixian Formation was deposited in the Early Cretaceous within a very short time period (ca. 2 Ma). Ó 2006 Published by Elsevier Ltd. Keywords: Zircon U-Pb SHRIMP dating; Yixian Formation; Feathered dinosaurs; Liaoning; Jehol Biota 1. Introduction still the subject of disagreement. Previously K-Ar and Rb-Sr dat- ing results for the volcanic rocks of the formation have yielded Recently, a wide variety of spectacular fossils, including the Jurassic ages of 137 Æ 7 Ma and 142.5 Æ 4Ma(Wang and Diao, ‘‘feathered dinosaurs’’ Sinosauropteryx (Chen et al., 1998), Pro- 1984). -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Second Edition

MASS ESTIMATES - DINOSAURS ETC (largely based on models) taxon k model femur length* model volume ml x specific gravity = model mass g specimen (modeled 1st):kilograms:femur(or other long bone length)usually in decameters kg = femur(or other long bone)length(usually in decameters)3 x k k = model volume in ml x specific gravity(usually for whole model) then divided/model femur(or other long bone)length3 (in most models femur in decameters is 0.5253 = 0.145) In sauropods the neck is assigned a distinct specific gravity; in dinosaurs with large feathers their mass is added separately; in dinosaurs with flight ablity the mass of the fight muscles is calculated separately as a range of possiblities SAUROPODS k femur trunk neck tail total neck x 0.6 rest x0.9 & legs & head super titanosaur femur:~55000-60000:~25:00 Argentinosaurus ~4 PVPH-1:~55000:~24.00 Futalognkosaurus ~3.5-4 MUCPv-323:~25000:19.80 (note:downsize correction since 2nd edition) Dreadnoughtus ~3.8 “ ~520 ~75 50 ~645 0.45+.513=.558 MPM-PV 1156:~26000:19.10 Giraffatitan 3.45 .525 480 75 25 580 .045+.455=.500 HMN MB.R.2181:31500(neck 2800):~20.90 “XV2”:~45000:~23.50 Brachiosaurus ~4.15 " ~590 ~75 ~25 ~700 " +.554=~.600 FMNH P25107:~35000:20.30 Europasaurus ~3.2 “ ~465 ~39 ~23 ~527 .023+.440=~.463 composite:~760:~6.20 Camarasaurus 4.0 " 542 51 55 648 .041+.537=.578 CMNH 11393:14200(neck 1000):15.25 AMNH 5761:~23000:18.00 juv 3.5 " 486 40 55 581 .024+.487=.511 CMNH 11338:640:5.67 Chuanjiesaurus ~4.1 “ ~550 ~105 ~38 ~693 .063+.530=.593 Lfch 1001:~10700:13.75 2 M. -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

The Molecular Evolution of Feathers with Direct Evidence from Fossils

The molecular evolution of feathers with direct evidence from fossils Yanhong Pana,1, Wenxia Zhengb, Roger H. Sawyerc, Michael W. Penningtond, Xiaoting Zhenge,f, Xiaoli Wange,f, Min Wangg,h, Liang Hua,i, Jingmai O’Connorg,h, Tao Zhaoa, Zhiheng Lig,h, Elena R. Schroeterb, Feixiang Wug,h, Xing Xug,h, Zhonghe Zhoug,h,i,1, and Mary H. Schweitzerb,j,1 aChinese Academy of Sciences Key Laboratory of Economic Stratigraphy and Palaeogeography, Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology and Center for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Nanjing 210008, China; bDepartment of Biological Sciences, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27695; cDepartment of Biological Sciences, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC 29205; dAmbioPharm Incorporated, North Augusta, SC 29842; eInstitute of Geology and Paleontology, Lingyi University, Lingyi City, 27605 Shandong, China; fShandong Tianyu Museum of Nature, Pingyi, 273300 Shandong, China; gCAS Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; hCenter for Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100044 Beijing, China; iCollege of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, 100049 Beijing, China; and jNorth Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, NC 27601 Contributed by Zhonghe Zhou, December 15, 2018 (sent for review September 12, 2018; reviewed by Dominique G. Homberger and Chenxi Jia) Dinosaur fossils possessing integumentary appendages of various feathers in Anchiornis, barbules that interlock to form feather morphologies, interpreted as feathers, have greatly enhanced our vanes critical for flight have not been identified yet (12). -

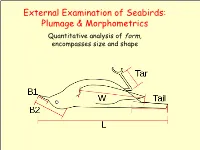

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Postcranial Skeletal Pneumaticity in Sauropods and Its

Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung by Mathew John Wedel B.S. (University of Oklahoma) 1997 A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Kevin Padian, Co-chair Professor William Clemens, Co-chair Professor Marvalee Wake Professor David Wake Professor John Gerhart Spring 2007 1 The dissertation of Mathew John Wedel is approved: Co-chair Date Co-chair Date Date Date Date University of California, Berkeley Spring 2007 2 Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung © 2007 by Mathew John Wedel 3 Abstract Postcranial Pneumaticity in Dinosaurs and the Origin of the Avian Lung by Mathew John Wedel Doctor of Philosophy in Integrative Biology University of California, Berkeley Professor Kevin Padian, Co-chair Professor William Clemens, Co-chair Among extant vertebrates, postcranial skeletal pneumaticity is present only in birds. In birds, diverticula of the lungs and air sacs pneumatize specific regions of the postcranial skeleton. The relationships among pulmonary components and the regions of the skeleton that they pneumatize form the basis for inferences about the pulmonary anatomy of non-avian dinosaurs. Fossae, foramina and chambers in the postcranial skeletons of pterosaurs and saurischian dinosaurs are diagnostic for pneumaticity. In basal saurischians only the cervical skeleton is pneumatized. Pneumatization by cervical air sacs is the most consilient explanation for this pattern. In more derived sauropods and theropods pneumatization of the posterior dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae indicates that abdominal air sacs were also present. -

Screaming Biplane Dromaeosaurs of the Air. June/July

5c.r~i~ ~l'tp.,ne pr~tl\USp.,urs 1tke.A-ir Written & illustrated by Gregory s. Paul It is questionable whether anyone even speculated that some dinosaurs were feathered until Ostrom detailed the evidence that birds descended from predatory avepod theropods a third of a century ago. The first illustration of a feathered dinosaur was a nice little study of a well ensconced Syntarsus dashing down a dune slope in pursuit of a gliding lizard in Robert Bakker's classic "Dinosaur Renaissance" article in the April 1975 Scientific American by Sarah Landry (can also be seen in the Scientific American Book of the Dinosaur I edited). My first feathered dinosaur was executed shortly after, an inappropriately shaggy Allosaurus attacking a herd of Diplodocus. I was soon doing a host of small theropods in feathers. Despite the logic of feath- / er insulation on the group ancestral birds and showing evidence of a high level energetics, images of feathered avepods were often harshly and unsci- Above: Proposed relationships based on flight adaptations of entifically criticized as unscientific in view of the lack of evidence for their preserved skeletons and feathers of Archaeopteryx, a generalized presence, ignoring the equal fact that no one had found scales on the little Sinornithosaurus, and Confuciusornis, with arrows indicating dinosaurs either. derived adaptations not present in Archaeopteryx as described in In the 1980s I further proposed that the most bird-like, avepectoran text. Not to scale. dinosaurs - dromaeosaurs, troodonts, oviraptorosaurs, and later ther- izinosaurs _were not just close to birds and the origin of flight, but were see- appear to represent the remnants of wings converted to display devices. -

Colour De Verre Molds: Feather

REUSABLE MOLDS FOR GLASS CASTING With either product, clean the See our website’s Learn section for mold with a stiff nylon brush and/ more instructions about priming or toothbrush to remove any old Colour de Verre molds with ZYP. kiln wash or boron nitride. (This step can be skipped if the mold is Filling the Feather brand new.) The suggested fill weight for the Feather is 330 to 340 grams. The If you are using Hotline Primo most simple way to fill the Feather Primer, mix the product according mold is to weigh out 330 of fine to directions. Apply the Primo frit and to evenly distribute the frit Primer™ with a soft artist’s brush in the mold. Fire the mold and frit (not a hake brush) and use a hair according the Casting Schedule Feather dryer to completely dry the coat. below. This design is also a perfect Create feathers that are as fanci- Give the mold four to five thin, candidate for our Wafer-Thin ful or realistic as you like with even coats drying each coat with a technique. One can read more Colour de Verre’s Feather de- hair dryer before applying the about this at www.colourdeverre.- sign. Once feathers are cast, next. Make sure to keep the Primo they can be slumped into amaz- com/go/wafer. ing decorative or functional well stirred as it settles quickly. pieces. The mold should be totally dry before filling. There is no reason to nnn pre-fire the mold. To use ZYP, hold the can 10 to 12 Feathers are a design element that inches from the mold.