Screaming Biplane Dromaeosaurs of the Air. June/July

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Chinese Archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx Gen. Nov

A Chinese archaeopterygian, Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. by Qiang Ji and Shu’an Ji Geological Science and Technology (Di Zhi Ke Ji) Volume 238 1997 pp. 38-41 Translated By Will Downs Bilby Research Center Northern Arizona University January, 2001 Introduction* The discoveries of Confuciusornis (Hou and Zhou, 1995; Hou et al, 1995) and Sinornis (Ji and Ji, 1996) have profoundly stimulated ornithologists’ interest globally in the Beipiao region of western Liaoning Province. They have also regenerated optimism toward solving questions of avian origins. In December 1996, the Chinese Geological Museum collected a primitive bird specimen at Beipiao that is comparable to Archaeopteryx (Wellnhofer, 1992). The specimen was excavated from a marl 5.5 m above the sediments that produce Sinornithosaurus and 8-9 m below the sediments that produce Confuciusornis. This is the first documentation of an archaeopterygian outside Germany. As a result, this discovery not only establishes western Liaoning Province as a center of avian origins and evolution, it provides conclusive evidence for the theory that avian evolution occurred in four phases. Specimen description Class Aves Linnaeus, 1758 Subclass Sauriurae Haeckel, 1866 Order Archaeopterygiformes Furbringer, 1888 Family Archaeopterygidae Huxley, 1872 Genus Protarchaeopteryx gen. nov. Genus etymology: Acknowledges that the specimen possesses characters more primitive than those of Archaeopteryx. Diagnosis: A primitive archaeopterygian with claviform and unserrated dentition. Sternum is thin and flat, tail is long, and forelimb resembles Archaeopteryx in morphology with three talons, the second of which is enlarged. Ilium is large and elongated, pubes are robust and distally fused, hind limb is long and robust with digit I reduced and dorsally migrated to lie in opposition to digit III and forming a grasping apparatus. -

Theropod Teeth from the Upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New Morphotypes and Faunal Comparisons

Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons TERRY A. GATES, LINDSAY E. ZANNO, and PETER J. MAKOVICKY Gates, T.A., Zanno, L.E., and Makovicky, P.J. 2015. Theropod teeth from the upper Maastrichtian Hell Creek Formation “Sue” Quarry: New morphotypes and faunal comparisons. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 60 (1): 131–139. Isolated teeth from vertebrate microfossil localities often provide unique information on the biodiversity of ancient ecosystems that might otherwise remain unrecognized. Microfossil sampling is a particularly valuable tool for doc- umenting taxa that are poorly represented in macrofossil surveys due to small body size, fragile skeletal structure, or relatively low ecosystem abundance. Because biodiversity patterns in the late Maastrichtian of North American are the primary data for a broad array of studies regarding non-avian dinosaur extinction in the terminal Cretaceous, intensive sampling on multiple scales is critical to understanding the nature of this event. We address theropod biodiversity in the Maastrichtian by examining teeth collected from the Hell Creek Formation locality that yielded FMNH PR 2081 (the Tyrannosaurus rex specimen “Sue”). Eight morphotypes (three previously undocumented) are identified in the sample, representing Tyrannosauridae, Dromaeosauridae, Troodontidae, and Avialae. Noticeably absent are teeth attributed to the morphotypes Richardoestesia and Paronychodon. Morphometric comparison to dromaeosaurid teeth from multiple Hell Creek and Lance formations microsites reveals two unique dromaeosaurid morphotypes bearing finer distal denticles than present on teeth of similar size, and also differences in crown shape in at least one of these. These findings suggest more dromaeosaurid taxa, and a higher Maastrichtian biodiversity, than previously appreciated. -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Second Edition

MASS ESTIMATES - DINOSAURS ETC (largely based on models) taxon k model femur length* model volume ml x specific gravity = model mass g specimen (modeled 1st):kilograms:femur(or other long bone length)usually in decameters kg = femur(or other long bone)length(usually in decameters)3 x k k = model volume in ml x specific gravity(usually for whole model) then divided/model femur(or other long bone)length3 (in most models femur in decameters is 0.5253 = 0.145) In sauropods the neck is assigned a distinct specific gravity; in dinosaurs with large feathers their mass is added separately; in dinosaurs with flight ablity the mass of the fight muscles is calculated separately as a range of possiblities SAUROPODS k femur trunk neck tail total neck x 0.6 rest x0.9 & legs & head super titanosaur femur:~55000-60000:~25:00 Argentinosaurus ~4 PVPH-1:~55000:~24.00 Futalognkosaurus ~3.5-4 MUCPv-323:~25000:19.80 (note:downsize correction since 2nd edition) Dreadnoughtus ~3.8 “ ~520 ~75 50 ~645 0.45+.513=.558 MPM-PV 1156:~26000:19.10 Giraffatitan 3.45 .525 480 75 25 580 .045+.455=.500 HMN MB.R.2181:31500(neck 2800):~20.90 “XV2”:~45000:~23.50 Brachiosaurus ~4.15 " ~590 ~75 ~25 ~700 " +.554=~.600 FMNH P25107:~35000:20.30 Europasaurus ~3.2 “ ~465 ~39 ~23 ~527 .023+.440=~.463 composite:~760:~6.20 Camarasaurus 4.0 " 542 51 55 648 .041+.537=.578 CMNH 11393:14200(neck 1000):15.25 AMNH 5761:~23000:18.00 juv 3.5 " 486 40 55 581 .024+.487=.511 CMNH 11338:640:5.67 Chuanjiesaurus ~4.1 “ ~550 ~105 ~38 ~693 .063+.530=.593 Lfch 1001:~10700:13.75 2 M. -

R~;: PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL

....----------- 'r~;: i ! 'r; Pa/eont .. 62(4), 1988, pp. 64~52 Copyright © 1988, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/88/0062-0640$03.00 PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL, CLIMATOLOGICAL, GEOPHYSICAL, SURVIVAL, AND EVOLUTIONARY IMPLICATIONS OF CRETACEOUS POLAR DINOSAURS GREGORY S. PAUL 3109 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 ABSTRACTT- he presence of Late Cretaceous social dinosaurs in polar regions confronted them with winter conditions of extended dark, coolness, breezes, and precipitation that could best be coped with via an endothermic homeothermic physiology of at least the tenrec level. This is true whether the dinosaurs stayed year round in the polar regime-which in North America extended from Alaska south to Montana-or if they migrated away from polar winters. More reptilian physiologies fail to meet the demands of such winters -in certain key ways, a· point tentatively confirmed by the apparent failure of giant Late Cretaceous phobosuchid crocodilians to dwell north of Montana. Low metabolisms were also insufficient for extended annual migrations away from and towards the poles. It is shown that even high metabolic rate dinosaurs probably remained in their polar habitats year-round. The possibility that dinosaurs had avian-mammalian metabolic systems, and may have borne insulation at least seasonally, severely limits their use as polar paleoclimatic and Earth axial tilt indicators. Polar dinosaurs may have been a center of dinosaur evolution. The possible ability of polar dinosaurs to cope with conditions of cool and dark challenges theories that a gradual temperature decline, or a sudden, meteoritic or volcanic induced collapse in temperature and sunlight, destroyed the dinosaurs. INTRODUCTION America suggests that dinosaurs were regularly crossing, and NCREASINGNUMBERSof remains show that dinosaurs lived living upon, the Bering Land Bridge within a few degrees of the I near the North and South Poles during the Cretaceous. -

State of the Palaeoart

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org State of the Palaeoart Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway The discipline of palaeoart, a branch of natural history art dedicated to the recon- struction of extinct life, is an established and important component of palaeontological science and outreach. For more than 200 years, palaeoartistry has worked closely with palaeontological science and has always been integral to the enduring popularity of prehistoric animals with the public. Indeed, the perceived value or success of such products as popular books, movies, documentaries, and museum installations can often be linked to the quality and panache of its palaeoart more than anything else. For all its significance, the palaeoart industry ment part of this dialogue in the published is often poorly treated by the academic, media and literature, in turn bringing the issues concerned to educational industries associated with it. Many wider attention. We argue that palaeoartistry is standard practises associated with palaeoart pro- both scientifically and culturally significant, and that duction are ethically and legally problematic, stifle improved working practises are required by those its scientific and cultural growth, and have a nega- involved in its production. We hope that our views tive impact on the financial viability of its creators. inspire discussion and changes sorely needed to These issues create a climate that obscures the improve the economy, quality and reputation of the many positive contributions made by palaeoartists palaeoart industry and its contributors. to science and education, while promoting and The historic, scientific and economic funding derivative, inaccurate, and sometimes exe- significance of palaeoart crable artwork. -

Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in Later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous Asiamerica Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2020-0174.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the 04-Jan-2021 Author: Complete List of Authors: Holtz, Thomas; University of Maryland at College Park, Department of Geology; NationalDraft Museum of Natural History, Department of Geology Keyword: Dinosaur, Ontogeny, Theropod, Paleocology, Mesozoic, Tyrannosauridae Is the invited manuscript for consideration in a Special Tribute to Dale Russell Issue? : © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Page 1 of 91 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Theropod Guild Structure and the Tyrannosaurid Niche Assimilation Hypothesis: 2 Implications for Predatory Dinosaur Macroecology and Ontogeny in later Late Cretaceous 3 Asiamerica 4 5 6 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 7 8 Department of Geology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA 9 Department of Paleobiology, National Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC 20013 USA 10 Email address: [email protected] 11 ORCID: 0000-0002-2906-4900 Draft 12 13 Thomas R. Holtz, Jr. 14 Department of Geology 15 8000 Regents Drive 16 University of Maryland 17 College Park, MD 20742 18 USA 19 Phone: 1-301-405-4084 20 Fax: 1-301-314-9661 21 Email address: [email protected] 22 23 1 © The Author(s) or their Institution(s) Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Page 2 of 91 24 ABSTRACT 25 Well-sampled dinosaur communities from the Jurassic through the early Late Cretaceous show 26 greater taxonomic diversity among larger (>50kg) theropod taxa than communities of the 27 Campano-Maastrichtian, particularly to those of eastern/central Asia and Laramidia. -

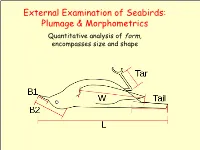

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

A Bird's Eye View of the Evolution of Avialan Flight

Chapter 12 Navigating Functional Landscapes: A Bird’s Eye View of the Evolution of Avialan Flight HANS C.E. LARSSON,1 T. ALEXANDER DECECCHI,2 MICHAEL B. HABIB3 ABSTRACT One of the major challenges in attempting to parse the ecological setting for the origin of flight in Pennaraptora is determining the minimal fluid and solid biomechanical limits of gliding and powered flight present in extant forms and how these minima can be inferred from the fossil record. This is most evident when we consider the fact that the flight apparatus in extant birds is a highly integrated system with redundancies and safety factors to permit robust performance even if one or more components of their flight system are outside their optimal range. These subsystem outliers may be due to other adaptive roles, ontogenetic trajectories, or injuries that are accommodated by a robust flight system. This means that many metrics commonly used to evaluate flight ability in extant birds are likely not going to be precise in delineating flight style, ability, and usage when applied to transitional taxa. Here we build upon existing work to create a functional landscape for flight behavior based on extant observations. The functional landscape is like an evolutionary adap- tive landscape in predicting where estimated biomechanically relevant values produce functional repertoires on the landscape. The landscape provides a quantitative evaluation of biomechanical optima, thus facilitating the testing of hypotheses for the origins of complex biomechanical func- tions. Here we develop this model to explore the functional capabilities of the earliest known avialans and their sister taxa. -

Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past Reviewed by Mark P. Witton Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past. 2017. Written by Zoë Lescaze and Walton Ford. Taschen. 292 pages, ISBN 978-3-8365-5511-1 (English edition). € 75, £75, $100 (hardcover) Paleoart: Visions of the Prehistoric Past is a collection of palaeoartworks spanning 150 years of palaeoart history, from 1830 to the second half of the 20th century. This huge, supremely well-pre- sented book was primarily written by journalist, archaeological illustrator and art scholar Zoë Les- caze, with an introduction by artist Walton Ford (both are American, and use ‘paleoart’ over the European spelling ‘palaeoart’). Ford states that the genesis of the book reflects “the need for a paleo- art book that was more about the art and less about the paleo” (p. 12), and thus Paleoart skews towards artistic aspects of palaeoartistry rather than palaeontological theory or technical aspects of reconstructing extinct animal appearance. Ford and Lescaze are correct that this angle of palaeo- artistry remains neglected, and this puts Paleoart in prime position to make a big impact on this pop- ular, though undeniably niche subject. Paleoart is extremely well-produced and stun- ning to look at, a visual feast for anyone with an interest in classic palaeoart. 292 pages of thick, sturdy paper (9 chapters, hundreds of images, and four fold outs) and almost impractical dimensions (28 x 37.4 cm) make it a physically imposing, stately tome that reminds us why books belong on shelves and not digital devices. Focusing exclu- sively on 2D art, the layout is minimalist and clean, detail, unobscured by text and labelling. -

Hierarchical Clustering Analysis Suppcdr.Cdr

Distance Hierarchical joiningclustering 3.0 2.5 2.0 1.5 1.0 0.5 Sinosauropteryx Caudipteryx Eoraptor Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Megaraptora basal Coelurosauria Noasauridae Neotheropoda non-averostran T non-tyrannosaurid Dromaeosauridae basalmost Theropoda Oviraptorosauria Compsognathidae Therizinosauria T A yrannosauroidea Compsognathus roodontidae ves Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Richardoestesia Scipionyx Buitreraptor Compsognathus Troodon Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Juravenator Sinosauropteryx Juravenator Juravenator Sinosauropteryx Incisivosaurus Coelophysis Scipionyx Richardoestesia Compsognathus Compsognathus Compsognathus Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Compsognathus Richardoestesia Juravenator Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Buitreraptor Saurornitholestes Ichthyornis Saurornitholestes Ichthyornis Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Juravenator Scipionyx Buitreraptor Coelophysis Richardoestesia Coelophysis Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Coelophysis Richardoestesia Bambiraptor Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Velociraptor Juravenator Saurornitholestes Saurornitholestes Buitreraptor Coelophysis Coelophysis Ornitholestes Richardoestesia Richardoestesia Juravenator Saurornitholestes Velociraptor Saurornitholestes -

The Oldest Record of Ornithuromorpha from the Early Cretaceous of China

ARTICLE Received 6 Jan 2015 | Accepted 20 Mar 2015 | Published 5 May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7987 OPEN The oldest record of ornithuromorpha from the early cretaceous of China Min Wang1, Xiaoting Zheng2,3, Jingmai K. O’Connor1, Graeme T. Lloyd4, Xiaoli Wang2,3, Yan Wang2,3, Xiaomei Zhang2,3 & Zhonghe Zhou1 Ornithuromorpha is the most inclusive clade containing extant birds but not the Mesozoic Enantiornithes. The early evolutionary history of this avian clade has been advanced with recent discoveries from Cretaceous deposits, indicating that Ornithuromorpha and Enantiornithes are the two major avian groups in Mesozoic. Here we report on a new ornithuromorph bird, Archaeornithura meemannae gen. et sp. nov., from the second oldest avian-bearing deposits (130.7 Ma) in the world. The new taxon is referable to the Hongshanornithidae and constitutes the oldest record of the Ornithuromorpha. However, A. meemannae shows few primitive features relative to younger hongshanornithids and is deeply nested within the Hongshanornithidae, suggesting that this clade is already well established. The new discovery extends the record of Ornithuromorpha by five to six million years, which in turn pushes back the divergence times of early avian lingeages into the Early Cretaceous. 1 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China. 2 Institue of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Linyi, Shandong 276000, China. 3 Tianyu Natural History Museum of Shandong, Pingyi, Shandong 273300, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales 2019, Australia.