Alula Characteristics As Indicators of Golden-Cheeked Warbler Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

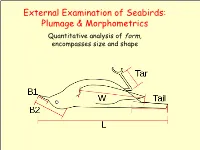

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Screaming Biplane Dromaeosaurs of the Air. June/July

5c.r~i~ ~l'tp.,ne pr~tl\USp.,urs 1tke.A-ir Written & illustrated by Gregory s. Paul It is questionable whether anyone even speculated that some dinosaurs were feathered until Ostrom detailed the evidence that birds descended from predatory avepod theropods a third of a century ago. The first illustration of a feathered dinosaur was a nice little study of a well ensconced Syntarsus dashing down a dune slope in pursuit of a gliding lizard in Robert Bakker's classic "Dinosaur Renaissance" article in the April 1975 Scientific American by Sarah Landry (can also be seen in the Scientific American Book of the Dinosaur I edited). My first feathered dinosaur was executed shortly after, an inappropriately shaggy Allosaurus attacking a herd of Diplodocus. I was soon doing a host of small theropods in feathers. Despite the logic of feath- / er insulation on the group ancestral birds and showing evidence of a high level energetics, images of feathered avepods were often harshly and unsci- Above: Proposed relationships based on flight adaptations of entifically criticized as unscientific in view of the lack of evidence for their preserved skeletons and feathers of Archaeopteryx, a generalized presence, ignoring the equal fact that no one had found scales on the little Sinornithosaurus, and Confuciusornis, with arrows indicating dinosaurs either. derived adaptations not present in Archaeopteryx as described in In the 1980s I further proposed that the most bird-like, avepectoran text. Not to scale. dinosaurs - dromaeosaurs, troodonts, oviraptorosaurs, and later ther- izinosaurs _were not just close to birds and the origin of flight, but were see- appear to represent the remnants of wings converted to display devices. -

The Oldest Record of Ornithuromorpha from the Early Cretaceous of China

ARTICLE Received 6 Jan 2015 | Accepted 20 Mar 2015 | Published 5 May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7987 OPEN The oldest record of ornithuromorpha from the early cretaceous of China Min Wang1, Xiaoting Zheng2,3, Jingmai K. O’Connor1, Graeme T. Lloyd4, Xiaoli Wang2,3, Yan Wang2,3, Xiaomei Zhang2,3 & Zhonghe Zhou1 Ornithuromorpha is the most inclusive clade containing extant birds but not the Mesozoic Enantiornithes. The early evolutionary history of this avian clade has been advanced with recent discoveries from Cretaceous deposits, indicating that Ornithuromorpha and Enantiornithes are the two major avian groups in Mesozoic. Here we report on a new ornithuromorph bird, Archaeornithura meemannae gen. et sp. nov., from the second oldest avian-bearing deposits (130.7 Ma) in the world. The new taxon is referable to the Hongshanornithidae and constitutes the oldest record of the Ornithuromorpha. However, A. meemannae shows few primitive features relative to younger hongshanornithids and is deeply nested within the Hongshanornithidae, suggesting that this clade is already well established. The new discovery extends the record of Ornithuromorpha by five to six million years, which in turn pushes back the divergence times of early avian lingeages into the Early Cretaceous. 1 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China. 2 Institue of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Linyi, Shandong 276000, China. 3 Tianyu Natural History Museum of Shandong, Pingyi, Shandong 273300, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales 2019, Australia. -

On the Role of the Alula in the Steady Flight of Birds

Ardeola 48(2), 2001, 161-173 ON THE ROLE OF THE ALULA IN THE STEADY FLIGHT OF BIRDS J. C. ÁLVAREZ*1, J. MESEGUER*, E. MESEGUER* & A. PÉREZ** SUMMARY.—On the role of the alula on the steady flight of birds. The alula is a high lift device located at the leading edge of the birds wings that allows these animals to fly at larger angles of attack and lower speeds without wing stalling. The influence of the alula in the wing aerodynamics is similar, to some extent, to that of leading edge slats in aircraft wings, which are only operative during take-off and landing operations. In this paper, representative parameters of the wing geometry including alula position and size of forty species of birds, are reported. The analysis of the reported data reveals that both alula size and position depend on the ae- rodynamic characteristics (wing load and aspect ratio) of the wing. In addition, aiming to clarify if the alula is deflected voluntarily by birds or if the deflection is caused by pressure forces, basic experimental results on the influence of the wing aerodynamics on the mechanism of alula deflection at low velocities are presented. Experimental results seem to indicate that the alula is deflected by pressure forces and not voluntarily. Key words: Alula, high lift devices, steady flight, wing load. RESUMEN.—El papel del álula en el vuelo estacionario de las aves. El álula es un dispositivo hipersus- tentador situado en el borde de ataque de las alas de los pájaros que permite que estos animales vuelen a altos ángulos de ataque y bajas velocidades sin que se produzca la entrada en pérdida del ala (el ala deja de sus- tentar si el ángulo de ataque es muy grande). -

Breeding Seasons, Molt Patterns, and Gender and Age Criteria for Selected Northeastern Costa Rican Resident Landbirds

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121(3):556–567, 2009 BREEDING SEASONS, MOLT PATTERNS, AND GENDER AND AGE CRITERIA FOR SELECTED NORTHEASTERN COSTA RICAN RESIDENT LANDBIRDS JARED D. WOLFE,1,2,4 PETER PYLE,3 AND C. JOHN RALPH2 ABSTRACT.—Detailed accounts of molt and breeding cycles remain elusive for the majority of resident tropical bird species. We used data derived from a museum review and 12 years of banding data to infer breeding seasonality, molt patterns, and age and gender criteria for 27 common landbird species in northeastern Costa Rica. Prealternate molts appear to be rare, only occurring in one species (Sporophila corvina), while presupplemental molts were not detected. Most of our study species (70%) symmetrically replace flight feathers during the absence of migrant birds; molting during this period may limit resource competition during an energetically taxing phase of the avian life-cycle. Received 30 August 2008. Accepted 19 February 2009. Temporal patterns of molt and breeding sea- of the avian life cycle, but other factors including sonality are largely unknown for many resident climate and resource availability may also affect tropical species (Dickey and van Rossem 1938, timing of molt (Aidley and Wilkinson 1987, Snow and Snow 1964, Snow 1976) in contrast to Bensch et al. 1991, Jones 1995). Little has been Nearctic-Neotropic migrants (hereafter ‘mi- published concerning temporal patterns of molt grants’). One might assume differential molt among resident tropical species in relation to sequences and extent between latitudes given competition from overwintering migrants despite different natural histories of resident tropical birds continued interest in factors influencing timing of in relation to their migrant counterparts. -

The Chat Vol

The Chat Vol. 78 SUMMER 2014 No. 3 The Quarterly Bulletin of the Carolina Bird Club, Inc. The Ornithological Society of the Carolinas THE CHAT ISSN No. 0009-1987 Vol. 78 SUMMER 2014 No. 3 Editor Don Seriff, 7324 Linda Lake Drive Charlotte, NC 28215 [email protected] General Field Notes Editors North Carolina Christina Harvey South Carolina William Post Briefs for the Files Josh Southern Associate Editor Judy Walker THE CHAT is published quarterly by the Carolina Bird Club, Inc., 1809 Lakepark Drive, Raleigh NC 27612. Individual subscription price $25 per year. Periodicals postage paid at Pinehurst, NC 28374 and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to THE CHAT, Carolina Bird Club, Inc., 9 Quincy Place, Pinehurst, NC 28374. Copyright © 2014 by Carolina Bird Club, Inc. Except for purposes of review, material contained herein may not be reproduced without written permission of the Carolina Bird Club, Inc. Reports South Carolina Bird List South Carolina Bird Records Committee ........................... 81 General Field Notes First Record of MacGillivray’s Warbler for South Carolina Aaron Given ................. 88 Fifty Years Ago in The Chat September 1964 .......................................................................................................... 93 Briefs for the Files Spring 2014 Josh Southern ......................................................................................... 94 Cover: Ruby-throated Hummingbird and coral honeysuckle (Lonicera sempervirens). Original watercolor by Leigh Anne Carter. LACarter.com South Carolina Bird List South Carolina Bird Records Committee [email protected] Received 12 October 2014 As a service to the scientific and birding communities, The Chat periodically publishes the official lists of the birds of North Carolina and of South Carolina. Current state lists, including the scientific names of each species, are also maintained on-line at: http://www.carolinabirdclub.org/brc/ Below is the South Carolina Bird Records Committee’s list of South Carolina birds, as of October 2014. -

The Feather Tracts of Swifts and Hummingbirds

68 CLARK,Pterylosis o/Swt/ls and Hummingbirds. [Jan.[Auk bird. There is no evidencethat griseusinterbreeds with marianet, and I think it shouldbe givefull specificrank. The breeding rangeof griseusextends along the South Carolinacoast as far no•Xhas the •nouthof the SanteeRiver. A glanceat the •nap of South Carolina, will showthat thcre are no salt m•rshcsof any ' extentfrom Georgetown to Southport, N. C., in whichthis wren could breed. THE FEATHER TRACTS OF SWIFTS AND HUMMINGBIRDS. BY HUBERT LYMAN CLARK. Plates II and III. SOMEyears ago I undertookto obtain•naterial for a studyof the arrange•nentof the feathertracts in the Swiftsand Hmmning- birds. Through the kindnessof the authoritiesof the United States National Museran, the alcoholic •naterial in that collection wasplaced at •ny disposal,and wascarefully exmnined. Later on, stonebeautiful hunnningbird•naterial frmn Arizona carne into•ny possession through the effortsof Mr. R. D. Lusk,and in 1897,Mr. C. B. Taylor of Kingston,Jmnaica, presented •ne with somevery valuable speci•nens of both swifts and hmmningbirds. In April,1901, a briefstate•nent appear.ed in 'The Auk' concern- ingthe conclusionsto which the study of this•naterial had led •ne, and a •noreextended reference to the•n appearedin 'Science'for January17, 1902. The preparationof theentire report, however, wascontinually postponed in the hopeof obtaining•nore speci- •nens,and in July,1905, through the kindness of Dr. Wit•nerStone, stonealcoholic hmmningbirds frown Brazil wereloaned •ne by the Academyof Natural Sciencesof Philadelphia. As thereis little Vol.1906 XXIII] j CJ,AI•Xr,Pterylosis o[Swi]ts and Hummingbirds. 69 probabilityat presentof securingin this countryfurther material of importance,I havedecided to delayno longerthe publication of this account of the work that has been done and the conclusions reached. -

The Morphological Basis of the Arm-To-Wing Transition

REVIEWARTICLE TheMorphologicalBasisoftheArm-to-Wing Transition SamuelO.Poore,MD,PhD Human-powered flight has fascinated scientists, artists, and physicians for centuries. This history includes Abbas Ibn Firnas, a Spanish inventor who attempted the first well-documented human flight; Leonardo da Vinci and his flying machines; the Turkish inventor Hezarfen Ahmed Celebi; and the modern aeronautical pioneer Otto Lilienthal. These historic figures held in common their attempts to construct wings from man-made materials, and though their human-powered attempts at flight never came to fruition, the ideas and creative elements contained within their flying machines were essential to modern aeronautics. Since the time of these early pioneers, flight has continued to captivate humans, and recently, in a departure from creating wings from artificial elements, there has been discussion of using reconstructive surgery to fabricate human wings from human arms. This article is a descriptive study of how one might attempt such a reconstruction and in doing so calls upon essential evidence in the evolution of flight, an understanding of which is paramount to constructing human wings from arms. This includes a brief analysis and exploration of the anatomy of the 150-million-year-oldArchaeopteryx lithographicafossil , with particular emphasis on the skeletal organization of this primitive bird’s wing and wrist. Additionally, certain elements of the reconstruction must be drawn from an analysis of modern birds including a description of the specialized shoulder of the EuropeanSturnus starling, vulgaris . With this anatomic description in tow, basic calculations regarding wing loading and allometry suggest that human wings would likely be nonfunctional. However, with the proper reconstructive balance betweenArchaeopteryx primitive) and ( modernSturnus ),( and in attempting to integrate a careful analysis of bird anatomy with modern surgical techniques, the newly constructed human wings could functioncosmetic asfeatures simulating, for example, the nonfunctional wings of flightless birds. -

First Report of the Palau Bird Records Committee

FIRST REPORT OF THE PALAU BIRD RECORDS COMMITTEE DEMEI OTOBED, ALAN R. OLSEN†, and MILANG EBERDONG, Belau National Museum, P.O. Box 666, Koror, Palau 96940 HEATHER KETEBENGANG, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940; [email protected] MANDY T. ETPISON, Etpison Museum, P.O. Box 7049, Koror, Palau 96940 H. DOUGLAS PRATT, 1205 Selwyn Lane, Cary, North Carolina 27511 GLENN H. MCKINLAY, C/55 Albert Road, Devonport, Auckland 0624, New Zealand GARY J. WILES, 521 Rogers St. SW, Olympia, Washington 98502 ERIC A. VANDERWERF, Pacific Rim Conservation, P.O. Box 61827, Honolulu, Hawaii 96839 MARK O’BRIEN, BirdLife International Pacific Regional Office, 10 MacGregor Road, Suva, Fiji RON LEIDICH, Planet Blue Kayak Tours, P.O. Box 7076, Koror, Palau 96940 UMAI BASILIUS and YALAP YALAP, Palau Conservation Society, P.O. Box 1181, Koror, Palau 96940 ABSTRACT: After compiling a historical list of 158 species of birds known to occur in Palau, the Palau Bird Records Committee accepted 10 first records of new occur- rences of bird species: the Common Pochard (Aythya ferina), Black-faced Spoonbill (Platalea minor), Chinese Pond Heron (Ardeola bacchus), White-breasted Waterhen (Amaurornis phoenicurus), Eurasian Curlew (Numenius arquata), Gull-billed Tern (Gelochelidon nilotica), Channel-billed Cuckoo (Scythrops novaehollandiae), Ruddy Kingfisher (Halcyon coromanda), Common Kingfisher (Alcedo atthis), and Isabelline Wheatear (Oenanthe isabellina). These additions bring Palau’s total list of accepted species to 168. We report Palau’s second records of the Broad-billed Sandpiper (Calidris falcinellus), Chestnut-winged Cuckoo (Clamator coromandus), Channel- billed Cuckoo, White-throated Needletail (Hirundapus caudacutus) and Oriental Reed Warbler (Acrocephalus orientalis). -

Wing Injuries- Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment- Kimberly a Mcmunn MS, MPH, DVM, CWR, CPH

Wing Injuries- Approach to Diagnosis and Treatment- Kimberly A McMunn MS, MPH, DVM, CWR, CPH Birds are highly adapted to flight, and preservation of flight capabilities is integral to the rehabilitation process. Each rehabilitator needs to work closely with a veterinarian to diagnose and treat the cause of an inability to fly. Rehabilitators are vital to the recovery of birds, providing necessary care and physical therapy during and after treatment/surgery. This talk will cover aspects of diagnosing and treatment of wing injures, from the perspective of the veterinarian. It will cover best approaches to various types of wing injures, as well as after-care and physical therapy recommendations. Wing injuries are extremely common in wild avian patients, often secondary to trauma. Early identification of wing injuries is critical to optimize the long-term prognosis, as is getting the bird to a veterinarian for care as soon as it is stabilized. Veterinarians are responsible for animal welfare, and are the experts best suited to evaluate a patient’s long-term prognosis.5 The goal of rehabilitation is to return our patients to the wild, which requires return to normal function. If a wild bird is unable to fly, forage, migrate, attract a mate, breed, and avoid predators, euthanasia may be the kindest option.5 Normal avian anatomy must be understood before it is possible to recognize and identify wing injuries. As mammals, we generally have a good comparison of human to mammalian anatomy. Birds are different in that they are highly adapted for flight, and the wing is most comparable to the mammalian forelimb. -

Subalular Apterium in Birds

THE AUK A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF ORNITHOLOGY VoL. 89 Ai, mL 1972 No. 2 SUBALULAR APTERIUM IN BIRDS WILLIAM G. GEORGE AND CLARK L. CASLER AN apterium, which evidently has remainedundescribed, exists under the alula of many avian speciesbut not by any meansin all groups. We first noted it in the Snakebird (Anhinga anhinga) in which the un- featheredarea, measuringabout 850 sq mm, is createdby an absenceof most upper median and other small upper wing covertsassociated with primaries1 (innermost) through6 (Figures 1A, lB). In an ordinary museumskin this apterium is apt to escapenotice, being shut away behind a dry, inflexible alula. Details of subalular plumage are difficult to see in skins for the same reason,and at first we soughtto limit our investigationto specimensin spirits and to freshly- collectedand living birds. But this kind of material proved available for only a few forms. Consequentlywe often resortedto dampeningthe wings of skins with a weak solutionof ethyl alcohol and examiningas much of the subalular area as could be glimpsedby slightly deflecting the alula. The present paper attempts to summarizeour still very incomplete knowledgeof the presenceand absenceof subalular apteria throughout the class. As used below, the term "apterium" refers to an absenceor size reduction of coverts which, as we interpret the evolutionary evi- dence, converted a once almost fully feathered region into a partly naked expanse. A wide variety of conditions intermediate between a well-marked apterium, as seen in Anhinga, and a feathered subalular region,as seenin most species,of courseexists. A showof skin may arise variously from loss of a few or many coverts,from size reductionof a few or many coverts,and from combinationsof both thesecircumstances. -

How Do Birdsfly?

▼ oung Y naturalists Birds take to the sky and safely return to land or water in marvelously different ways. RED-TAILED HAWK BY BILL MARCHEL air air wing By Carrol HendersonHow Doand Michael Birds A. Kallok Fly? air ILLUSTRATION BY ILLUSTRATION STEVE ADAMS air For thousands of years, humans have watched with wonder air and envy as birds fly. People first tried to fly like birds by imitating the flapping of wings. In the late 1400s, Leonardo da Vinci created a wing- flapping contraption called an orni- When a bird or airplane is moving through the air, the air thopter (from the Greek word orni- splits its path at the front edge of the wing and meets again at thos for bird and pteron for wing). the back of the wing. Because the top of the wing is curved, He thought flying was simply a mat- the distance from the front of the wing to the back of the wing ter of flapping wings up and down. The ornithopter didn’t Discoveryis shorter of a for force air passing called under the lift wing. Air passing over the work because he did not understand how bird wings must wing top moves more quickly than air under the bottom. The generate lift and thrust to fly. fast-moving air atop the wing creates less pressure than air Today, airplanes with powerful engines can fly long underneath the wing. The higher air pressure under the wing distances. But human-made machines will probably lifts the bird upward. At the same time, wing flapping acts never match the natural power and grace of birds on the like a propeller to move, or thrust, the bird forward.