Subalular Apterium in Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

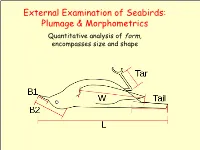

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Screaming Biplane Dromaeosaurs of the Air. June/July

5c.r~i~ ~l'tp.,ne pr~tl\USp.,urs 1tke.A-ir Written & illustrated by Gregory s. Paul It is questionable whether anyone even speculated that some dinosaurs were feathered until Ostrom detailed the evidence that birds descended from predatory avepod theropods a third of a century ago. The first illustration of a feathered dinosaur was a nice little study of a well ensconced Syntarsus dashing down a dune slope in pursuit of a gliding lizard in Robert Bakker's classic "Dinosaur Renaissance" article in the April 1975 Scientific American by Sarah Landry (can also be seen in the Scientific American Book of the Dinosaur I edited). My first feathered dinosaur was executed shortly after, an inappropriately shaggy Allosaurus attacking a herd of Diplodocus. I was soon doing a host of small theropods in feathers. Despite the logic of feath- / er insulation on the group ancestral birds and showing evidence of a high level energetics, images of feathered avepods were often harshly and unsci- Above: Proposed relationships based on flight adaptations of entifically criticized as unscientific in view of the lack of evidence for their preserved skeletons and feathers of Archaeopteryx, a generalized presence, ignoring the equal fact that no one had found scales on the little Sinornithosaurus, and Confuciusornis, with arrows indicating dinosaurs either. derived adaptations not present in Archaeopteryx as described in In the 1980s I further proposed that the most bird-like, avepectoran text. Not to scale. dinosaurs - dromaeosaurs, troodonts, oviraptorosaurs, and later ther- izinosaurs _were not just close to birds and the origin of flight, but were see- appear to represent the remnants of wings converted to display devices. -

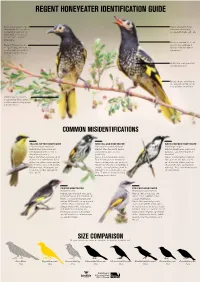

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Comparative Bathing Behavior in Some Australian Birds

J. Field Ornithol., 62(3):386-389 COMPARATIVE BATHING BEHAVIOR IN SOME AUSTRALIAN BIRDS N. A.M. VE•EEK Departmentof BiologicalSciences SimonFraser University Burnaby,British ColumbiaV5A IS6, Canada Abstract.--The bathingbehavior of Alcedinidae(2 species),Dicruridae (1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae (5) and Zosteropidae(1) is describedand compared with that of other species.The birds were observedfrom a blind while they bathed in a water hole with a sloping shore line and flanked on one side by shrubs.Two forms of bathing were noted: diving from shrubsand wading into shallow water. Although more data are needed,it is suggestedthat the bathing methodsused by birds differ at the generic level and not necessarilyat the family level. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DE LA CONDUCTA DE BAI•ARSE POR ALGUNAS AVES AUSTRALIANAS Sinopsis.--Sedescribe y comparala conductade bafiarsede Alcedinidae(2 especies),Di- cruridae(1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae(5) y Zosteropidae(1) con la de otras especies.Las avesse observarondesde escondijos mientras se bafiabanen un ojo de agua flanquedoen un lado pot arbustos.Se noratondos formas de bafiarse:tiffindose en clavado desdeun arbusto y andando o brincando desdela orilla hacia agua de poca pro- fundidad.Aunque se necesitanmils datos,sugiero que el m•todo de bafiarseutilizado pot las avesdifiere a nivel de g•nero y no necesariamentea nivel de familia. Although someforms of feather maintenancebehavior have been stud- ied in detail (e.g.,preening, Hatch et al. 1986, Ierseland Bol 1958) others (e.g., bathing) are rarely mentionedin the bird literature (Burtt 1983). As most feather maintenanceactivities occur infrequently and unpre- dictablyand are often of short duration, they are difficult to study sys- tematically.Simmons (1964) and Slessers(1970) reportedon the different bathing techniquesof birds and made the first attemptsto compareand interpret them in terms of morphologyand ecology.The observations here reported show that theseinterpretations may have to be modified. -

The Oldest Record of Ornithuromorpha from the Early Cretaceous of China

ARTICLE Received 6 Jan 2015 | Accepted 20 Mar 2015 | Published 5 May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7987 OPEN The oldest record of ornithuromorpha from the early cretaceous of China Min Wang1, Xiaoting Zheng2,3, Jingmai K. O’Connor1, Graeme T. Lloyd4, Xiaoli Wang2,3, Yan Wang2,3, Xiaomei Zhang2,3 & Zhonghe Zhou1 Ornithuromorpha is the most inclusive clade containing extant birds but not the Mesozoic Enantiornithes. The early evolutionary history of this avian clade has been advanced with recent discoveries from Cretaceous deposits, indicating that Ornithuromorpha and Enantiornithes are the two major avian groups in Mesozoic. Here we report on a new ornithuromorph bird, Archaeornithura meemannae gen. et sp. nov., from the second oldest avian-bearing deposits (130.7 Ma) in the world. The new taxon is referable to the Hongshanornithidae and constitutes the oldest record of the Ornithuromorpha. However, A. meemannae shows few primitive features relative to younger hongshanornithids and is deeply nested within the Hongshanornithidae, suggesting that this clade is already well established. The new discovery extends the record of Ornithuromorpha by five to six million years, which in turn pushes back the divergence times of early avian lingeages into the Early Cretaceous. 1 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China. 2 Institue of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Linyi, Shandong 276000, China. 3 Tianyu Natural History Museum of Shandong, Pingyi, Shandong 273300, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales 2019, Australia. -

Alula Characteristics As Indicators of Golden-Cheeked Warbler Age

Alula Characteristics as Indicators of Golden-cheeked Warbler Age Rebecca G. Peak and Daniel J. Lusk (SY) birds from older age classes. Dwight (1900) P.O. Box 5190 first illustrated the utility of molt limits in ageing Fort Hood, TX 76544 passerines. More recent literature on the use of molt [email protected] limits to age North American passerines provide detailed descriptions ofhow to distinguish different feather generations from each other for a variety of ABSTRACT species (Yunick 1984, Pyle et al. 1987, Mulvihill 1993, Pyle 1997a, Pyle 1997b ). We assessed the alula ofGolden-cheeked Warblers (Dendroica chrysoparia) to determine its usefulness Dendroica warblers retain greater primary coverts as a criterion for age determination. We compared (hereafter "primary coverts") from the juvenal the alula to the greater secondary coverts for color plumage but replace greater secondary coverts contrast and examined it for presence of white. (hereafter "greater coverts") during the first Overall, 98.2% ofsecond-year birds had an alula/ prebasic molt (Pyle et al. 1987). Hence, greater secondary covert contrast; whereas, I 00% comparison of color and extent of wear between of after-second-year birds did not have a contrast these feather groups is useful for ageing members between these feather groups. All after-second of this genus. The contrast between primary and year birds had white on the alula. Our data greater coverts can be challenging for inexperi demonstrate that these characteristics are reliable enced banders to recognize. These feather groups indicators of age for Golden-cheeked Warblers. are small, the color difference is often difficult for Still, we advocate using them in combination with the untrained eye to discern, and some of these existing ageing criteria to enhance the confidence species replace the inner greater coverts during of banders' age determinations, especially during prealternate molts. -

Or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 275, 279-280, 288 & 291-292. Order PASSERIFORMES: Passerine (Perching) Birds See Christidis & Boles (2008) for a review of recent studies relevant to the higher-level systematics of the passerine birds. Suborder PASSERES (or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds) The arrangement of songbirds in the 1970 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1970) was based on the premise that the species endemic to the Australasian region were derived directly from Eurasian groups and belonged in Old World families (e.g. Gerygone and Petroica in Muscicapidae). The 1990 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1990) followed the Australian lead in allocating various native songbirds to their own Australasian families (e.g. Gerygone to Acanthizidae, and Petroica to Eopsaltriidae), but the sequence was still based largely on the old Peters-Mayr arrangement. Since the late 1980s, when the 1990 Checklist was finalised, evidence from molecular biology, especially DNA studies, has shown that most of the Australian and New Zealand endemic songbirds are the product of a major Australasian radiation parallel to the radiation of songbirds in Eurasia and elsewhere. Many superficial morphological and ecological similarities between Australasian and Eurasian songbirds are the result of convergent evolution. Sibley & Ahlquist (1985, 1990) and Sibley et al. (1988) recognised a division of the songbirds into two groups which were called Corvida and Passerida (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990). -

On the Role of the Alula in the Steady Flight of Birds

Ardeola 48(2), 2001, 161-173 ON THE ROLE OF THE ALULA IN THE STEADY FLIGHT OF BIRDS J. C. ÁLVAREZ*1, J. MESEGUER*, E. MESEGUER* & A. PÉREZ** SUMMARY.—On the role of the alula on the steady flight of birds. The alula is a high lift device located at the leading edge of the birds wings that allows these animals to fly at larger angles of attack and lower speeds without wing stalling. The influence of the alula in the wing aerodynamics is similar, to some extent, to that of leading edge slats in aircraft wings, which are only operative during take-off and landing operations. In this paper, representative parameters of the wing geometry including alula position and size of forty species of birds, are reported. The analysis of the reported data reveals that both alula size and position depend on the ae- rodynamic characteristics (wing load and aspect ratio) of the wing. In addition, aiming to clarify if the alula is deflected voluntarily by birds or if the deflection is caused by pressure forces, basic experimental results on the influence of the wing aerodynamics on the mechanism of alula deflection at low velocities are presented. Experimental results seem to indicate that the alula is deflected by pressure forces and not voluntarily. Key words: Alula, high lift devices, steady flight, wing load. RESUMEN.—El papel del álula en el vuelo estacionario de las aves. El álula es un dispositivo hipersus- tentador situado en el borde de ataque de las alas de los pájaros que permite que estos animales vuelen a altos ángulos de ataque y bajas velocidades sin que se produzca la entrada en pérdida del ala (el ala deja de sus- tentar si el ángulo de ataque es muy grande). -

'Island Rule' Apply to Birds?

Lincoln University Digital Thesis Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: you will use the copy only for the purposes of research or private study you will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of the thesis and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate you will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Does the ‘island rule’ apply to birds? An analysis of morphological variation between insular and mainland birds from the Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic region A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Conservation and Ecology) at Lincoln University by Elisa Diana Ruiz Ramos Lincoln University 2014 Abstract of a thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science (Conservation and Ecology) Abstract Does the ‘island rule’ apply to birds? An analysis of morphological variation between insular and mainland birds from the Australian, New Zealand and Antarctic region by Elisa Diana Ruiz Ramos The ‘island rule’ states that large animals become smaller and small animals become larger on islands. Morphological shifts on islands have been generalized for all vertebrates as a strategy to better exploit limited resources in constrained areas with low interspecific competition and predation pressures. In the case of birds, most of the studies that validate this rule have focused on passerines, and it is unclear about whether the rule applies to other Orders. -

Breeding Seasons, Molt Patterns, and Gender and Age Criteria for Selected Northeastern Costa Rican Resident Landbirds

The Wilson Journal of Ornithology 121(3):556–567, 2009 BREEDING SEASONS, MOLT PATTERNS, AND GENDER AND AGE CRITERIA FOR SELECTED NORTHEASTERN COSTA RICAN RESIDENT LANDBIRDS JARED D. WOLFE,1,2,4 PETER PYLE,3 AND C. JOHN RALPH2 ABSTRACT.—Detailed accounts of molt and breeding cycles remain elusive for the majority of resident tropical bird species. We used data derived from a museum review and 12 years of banding data to infer breeding seasonality, molt patterns, and age and gender criteria for 27 common landbird species in northeastern Costa Rica. Prealternate molts appear to be rare, only occurring in one species (Sporophila corvina), while presupplemental molts were not detected. Most of our study species (70%) symmetrically replace flight feathers during the absence of migrant birds; molting during this period may limit resource competition during an energetically taxing phase of the avian life-cycle. Received 30 August 2008. Accepted 19 February 2009. Temporal patterns of molt and breeding sea- of the avian life cycle, but other factors including sonality are largely unknown for many resident climate and resource availability may also affect tropical species (Dickey and van Rossem 1938, timing of molt (Aidley and Wilkinson 1987, Snow and Snow 1964, Snow 1976) in contrast to Bensch et al. 1991, Jones 1995). Little has been Nearctic-Neotropic migrants (hereafter ‘mi- published concerning temporal patterns of molt grants’). One might assume differential molt among resident tropical species in relation to sequences and extent between latitudes given competition from overwintering migrants despite different natural histories of resident tropical birds continued interest in factors influencing timing of in relation to their migrant counterparts.