Download This PDF File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat

Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Dedicated bird enthusiasts have kindly contributed to this sequence of 106 bird species spotted in the habitat over the last few years Kookaburra Red-browed Finch Black-faced Cuckoo- shrike Magpie-lark Tawny Frogmouth Noisy Miner Spotted Dove [1] Crested Pigeon Australian Raven Olive-backed Oriole Whistling Kite Grey Butcherbird Pied Butcherbird Australian Magpie Noisy Friarbird Galah Long-billed Corella Eastern Rosella Yellow-tailed black Rainbow Lorikeet Scaly-breasted Lorikeet Cockatoo Tawny Frogmouth c Noeline Karlson [1] ( ) Common Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Variegated Fairy- Yellow Faced Superb Fairy-wren White Cheeked Scarlet Honeyeater Blue-faced Honeyeater wren Honeyeater Honeyeater White-throated Brown Gerygone Brown Thornbill Yellow Thornbill Eastern Yellow Robin Silvereye Gerygone White-browed Eastern Spinebill [2] Spotted Pardalote Grey Fantail Little Wattlebird Red Wattlebird Scrubwren Willie Wagtail Eastern Whipbird Welcome Swallow Leaden Flycatcher Golden Whistler Rufous Whistler Eastern Spinebill c Noeline Karlson [2] ( ) Common Sea and shore birds Silver Gull White-necked Heron Little Black Australian White Ibis Masked Lapwing Crested Tern Cormorant Little Pied Cormorant White-bellied Sea-Eagle [3] Pelican White-faced Heron Uncommon Sea and shore birds Caspian Tern Pied Cormorant White-necked Heron Great Egret Little Egret Great Cormorant Striated Heron Intermediate Egret [3] White-bellied Sea-Eagle (c) Noeline Karlson Uncommon Birds in Tilligerry Habitat Grey Goshawk Australian Hobby -

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia

Birding Oxley Creek Common Brisbane, Australia Hugh Possingham and Mat Gilfedder – January 2011 [email protected] www.ecology.uq.edu.au 3379 9388 (h) Other photos, records and comments contributed by: Cathy Gilfedder, Mike Bennett, David Niland, Mark Roberts, Pete Kyne, Conrad Hoskin, Chris Sanderson, Angela Wardell-Johnson, Denis Mollison. This guide provides information about the birds, and how to bird on, Oxley Creek Common. This is a public park (access restricted to the yellow parts of the map, page 6). Over 185 species have been recorded on Oxley Creek Common in the last 83 years, making it one of the best birding spots in Brisbane. This guide is complimented by a full annotated list of the species seen in, or from, the Common. How to get there Oxley Creek Common is in the suburb of Rocklea and is well signposted from Sherwood Road. If approaching from the east (Ipswich Road side), pass the Rocklea Markets and turn left before the bridge crossing Oxley Creek. If approaching from the west (Sherwood side) turn right about 100 m after the bridge over Oxley Creek. The gate is always open. Amenities The main development at Oxley Creek Common is the Red Shed, which is beside the car park (plenty of space). The Red Shed has toilets (composting), water, covered seating, and BBQ facilities. The toilets close about 8pm and open very early. The paths are flat, wide and easy to walk or cycle. When to arrive The diversity of waterbirds is a feature of the Common and these can be good at any time of the day. -

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera Phrygia)

National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) April 2016 1 The Species Profile and Threats Database pages linked to this recovery plan is obtainable from: http://www.environment.gov.au/cgi-bin/sprat/public/sprat.pl © Copyright Commonwealth of Australia, 2016. The National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia) is licensed by the Commonwealth of Australia for use under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International licence with the exception of the Coat of Arms of the Commonwealth of Australia, the logo of the agency responsible for publishing the report, content supplied by third parties, and any images depicting people. For licence conditions see: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This report should be attributed as ‘National Recovery Plan for the Regent Honeyeater (Anthochaera phrygia), Commonwealth of Australia 2016’. The Commonwealth of Australia has made all reasonable efforts to identify content supplied by third parties using the following format ‘© Copyright, [name of third party] ’. Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the contents of this publication are factually correct, the Commonwealth does not accept responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of, or reliance on, the contents of this publication. Image credits Front Cover: Regent honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, NSW. (© Copyright, Dean Ingwersen). 2 -

The Relationships of the Starlings (Sturnidae: Sturnini) and the Mockingbirds (Sturnidae: Mimini)

THE RELATIONSHIPS OF THE STARLINGS (STURNIDAE: STURNINI) AND THE MOCKINGBIRDS (STURNIDAE: MIMINI) CHARLESG. SIBLEYAND JON E. AHLQUIST Departmentof Biologyand PeabodyMuseum of Natural History,Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut 06511 USA ABSTRACT.--OldWorld starlingshave been thought to be related to crowsand their allies, to weaverbirds, or to New World troupials. New World mockingbirdsand thrashershave usually been placed near the thrushesand/or wrens. DNA-DNA hybridization data indi- cated that starlingsand mockingbirdsare more closelyrelated to each other than either is to any other living taxon. Some avian systematistsdoubted this conclusion.Therefore, a more extensiveDNA hybridizationstudy was conducted,and a successfulsearch was made for other evidence of the relationshipbetween starlingsand mockingbirds.The resultssup- port our original conclusionthat the two groupsdiverged from a commonancestor in the late Oligoceneor early Miocene, about 23-28 million yearsago, and that their relationship may be expressedin our passerineclassification, based on DNA comparisons,by placing them as sistertribes in the Family Sturnidae,Superfamily Turdoidea, Parvorder Muscicapae, Suborder Passeres.Their next nearest relatives are the members of the Turdidae, including the typical thrushes,erithacine chats,and muscicapineflycatchers. Received 15 March 1983, acceptedI November1983. STARLINGS are confined to the Old World, dine thrushesinclude Turdus,Catharus, Hylocich- mockingbirdsand thrashersto the New World. la, Zootheraand Myadestes.d) Cinclusis -

Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia

June 2010 223 Recent Honeyeater Migration in Southern Australia BRYAN T HAYWOOD Abstract be seen moving through areas of south-eastern Australia during autumn (Ford 1983; Simpson & A conspicuous migration of honeyeaters particularly Day 1996). On occasions Fuscous Honeyeaters Yellow-faced Honeyeater, Lichenostomus chrysops, have been reported migrating in company with and White-naped Honeyeater, Melithreptus lunatus, Yellow-faced Honeyeaters, but only in small was observed in the SE of South Australia during numbers (Blakers et al., 1984). May and June 2007. A particularly significant day was 12 May 2007 when both species were Movements of honeyeaters throughout southern observed moving in mixed flocks in westerly and Australia are also predominantly up the east northerly directions in five different locations in the coast with birds moving from Victoria and New SE of South Australia. Migration of Yellow-faced South Wales (Hindwood 1956;Munro, Wiltschko Honeyeater and White-naped Honeyeater is not and Wiltschko 1993; Munro and Munro 1998) limited to following the coastline in the SE of South into southern Queensland. The timing and Australia, but also inland. During this migration direction at which these movements occur has period small numbers of Fuscous Honeyeater, L. been under considerable study with findings fuscus, were also observed. The broad-scale nature that birds (heading up the east coast) actually of these movements over the period April to June change from a north-easterly to north-westerly 2007 was indicated by records from south-western direction during this migration period. This Victoria, various locations in the SE of South change in direction is partly dictated by changes Australia, Adelaide and as far west as the Mid North in landscape features, but when Yellow-faced of SA. -

Regent Honeyeater Identification Guide

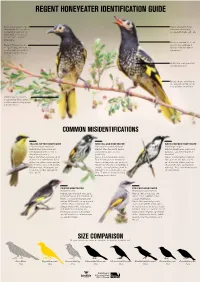

REGENT HONEYEATER IDENTIFICATION GUIDE Broad patch of bare warty Males call prominently, skin around the eye, which whereas females only is smaller in young birds occasionally make soft calls. and females. Best seen at close range or with binoculars. Plumage around the head Regent Honeyeaters are and neck is solid black 20-24 cm long, with females giving a slightly hooded smaller and having duller appearance. plumage than the males. Distinctive scalloped (not streaked) breast. Broad stripes of yellow in the wing when folded, and very prominent in flight. From below the tail is a bright yellow. From behind it’s black bordered by bright yellow feathers. COMMON MISIDENTIFICATIONS YELLOW-TUFTED HONEYEATER NEW HOLLAND HONEYEATER WHITE-CHEEKED HONEYEATER Lichenostomus melanops Phylidonyris novaehollandiae Phylidonyris niger Habitat: Box-Gum-Ironbark Habitat: Woodland with heathy Habitat: Heathlands, parks and woodlands and forest with a understorey, gardens and gardens, less commonly open shrubby understorey. parklands. woodland. Notes: Common, sedentary bird Notes: Often misidentified as a Notes: Similar to New Holland of temperate woodlands. Has a Regent Honeyeater; commonly Honeyeaters, but have a large distinctive yellow crown and ear seen in urban parks and gardens. patch of white feathers in their tuft in a black face, with a bright Distinctive white breast with black cheek and a dark eye (no white yellow throat. Underparts are streaks, several patches of white eye ring). Also have white breast plain dirty yellow, upperparts around the face, and a white eye streaked black. olive-green. ring. Tend to be in small, noisy and aggressive flocks. PAINTED HONEYEATER CRESCENT HONEYEATER Grantiella picta Phylidonyris pyrrhopterus Habitat: Box-Ironbark woodland, Habitat: Wetter habitats like particularly with fruiting mistletoe forest, dense woodland and Notes: A seasonal migrant, only coastal heathlands. -

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’S Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’S

Bird Guide for the Great Western Woodlands Male Gilbert’s Whistler: Chris Tzaros Whistler: Male Gilbert’s Western Australia PART 1. GWW NORTHERN Southern Cross Kalgoorlie Widgiemooltha birds are in our nature ® Australia AUSTRALIA Introduction The birds and places of the north-west region of the Great Western Woodlands are presented in this booklet. This area includes tall woodlands on red soils, shrublands on yellow sand plains and mallee on sand and loam soils. Landforms include large granite outcrops, Banded Ironstone Formation (BIF) Ranges, extensive natural salt lakes and a few freshwater lakes. The Great Western Woodlands At 16 million hectares, the Great Western Woodlands (GWW) is close to three quarters the size of Victoria and is the largest remaining intact area of temperate woodland in the world. It is located between the Western Australian Wheatbelt and the Nullarbor Plain. BirdLife Australia and The Nature Conservancy joined forces in 2012 to establish a long-term project to study the birds of this unique region and to determine how we can best conserve the woodland birds that occur here. Kalgoorlie 1 Groups of volunteers carry out bird surveys each year in spring and autumn to find out the species present, their abundance and to observe their behaviour. If you would like to know more visit http://www.birdlife.org.au/projects/great-western-woodlands If you would like to participate as a volunteer contact [email protected]. All levels of experience are welcome. The following six pages present 48 bird species that typically occur in four different habitats of the north-west region of the GWW, although they are not restricted to these. -

Comparative Bathing Behavior in Some Australian Birds

J. Field Ornithol., 62(3):386-389 COMPARATIVE BATHING BEHAVIOR IN SOME AUSTRALIAN BIRDS N. A.M. VE•EEK Departmentof BiologicalSciences SimonFraser University Burnaby,British ColumbiaV5A IS6, Canada Abstract.--The bathingbehavior of Alcedinidae(2 species),Dicruridae (1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae (5) and Zosteropidae(1) is describedand compared with that of other species.The birds were observedfrom a blind while they bathed in a water hole with a sloping shore line and flanked on one side by shrubs.Two forms of bathing were noted: diving from shrubsand wading into shallow water. Although more data are needed,it is suggestedthat the bathing methodsused by birds differ at the generic level and not necessarilyat the family level. ESTUDIO COMPARATIVO DE LA CONDUCTA DE BAI•ARSE POR ALGUNAS AVES AUSTRALIANAS Sinopsis.--Sedescribe y comparala conductade bafiarsede Alcedinidae(2 especies),Di- cruridae(1), Meliphagidae (16), Meropidae (1), Muscicapidae(5) y Zosteropidae(1) con la de otras especies.Las avesse observarondesde escondijos mientras se bafiabanen un ojo de agua flanquedoen un lado pot arbustos.Se noratondos formas de bafiarse:tiffindose en clavado desdeun arbusto y andando o brincando desdela orilla hacia agua de poca pro- fundidad.Aunque se necesitanmils datos,sugiero que el m•todo de bafiarseutilizado pot las avesdifiere a nivel de g•nero y no necesariamentea nivel de familia. Although someforms of feather maintenancebehavior have been stud- ied in detail (e.g.,preening, Hatch et al. 1986, Ierseland Bol 1958) others (e.g., bathing) are rarely mentionedin the bird literature (Burtt 1983). As most feather maintenanceactivities occur infrequently and unpre- dictablyand are often of short duration, they are difficult to study sys- tematically.Simmons (1964) and Slessers(1970) reportedon the different bathing techniquesof birds and made the first attemptsto compareand interpret them in terms of morphologyand ecology.The observations here reported show that theseinterpretations may have to be modified. -

Eastern Australia: October-November 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN AUSTRALIA: From Top to Bottom 23rd October – 11th November 2016 The bird of the trip, the very impressive POWERFUL OWL Tour Leader: Laurie Ross All photos in this report were taken by Laurie Ross/Tropical Birding. 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report Eastern Australia: October-November 2016 INTRODUCTION The Eastern Australia Set Departure Tour introduces a huge amount of new birds and families to the majority of the group. We started the tour in Cairns in Far North Queensland, where we found ourselves surrounded by multiple habitats from the tidal mudflats of the Cairns Esplanade, the Great Barrier Reef and its sandy cays, lush lowland and highland rainforests of the Atherton Tablelands, and we even made it to the edge of the Outback near Mount Carbine; the next leg of the tour took us south to Southeast Queensland where we spent time in temperate rainforests and wet sclerophyll forests within Lamington National Park. The third, and my favorite leg, of the tour took us down to New South Wales, where we birded a huge variety of new habitats from coastal heathland to rocky shorelines and temperate rainforests in Royal National Park, to the mallee and brigalow of Inland New South Wales. The fourth and final leg of the tour saw us on the beautiful island state of Tasmania, where we found all 13 “Tassie” endemics. We had a huge list of highlights, from finding a roosting Lesser Sooty Owl in Malanda; to finding two roosting Powerful Owls near Brisbane; to having an Albert’s Lyrebird walk out in front of us at O Reilly’s; to seeing the rare and endangered Regent Honeyeaters in the Capertee Valley, and finding the endangered Swift Parrot on Bruny Island, in Tasmania. -

Canberra Bird Notes

ISSN 0314-8211 CANBERRA Volume 21 Number 3 BIRD September 1996 NOTES Registered by Australia Post - publication No NBH 0255 CANBERRA ORNITHOLOGISTS GROUP INC. P.O. Box 301, Civic Square, ACT 2608 Committee Members (1996) Work Home President Paul Fennell 254 1804 Vice-President Jenny Bounds 288 7802 (mobile 014 63 5249) Secretary Susan Newbery 254 0960 Treasurer John Avery 281 4631 Member Mark Clayton 241 3620 Member Gwen Hartican 281 3622 Member David Landon 254 2334 Member Carol Macleay 286 2624 Member Andrew Newbery 254 0960 Member Anthony Overs Member Margaret Palmer 282 3011 Member Harvey Perkins 231 8209 Member Richard Schodde 242 1693 281 3732 The following people represent Canberra Ornithologists Group in various ways although they may not be formally on the Committee: ADP Support Cedric Bear 258 3169 Australian Bird Count Chris Davey 242 1600 254 6324 Barren Grounds, Representative Tony Lawson 288 9430 Canberra Bird Notes, Editor David Purchase 258 2252 258 2252 Assistant Editor Grahame Clark 254 1279 Conservation Council, Representatives < Bruce Lindenmayer 288 5957 288 5957 Jenny Bounds 288 7802 (mobile 014 63 5249) Anthony Overs Exhibitions Coordinator Margaret Palmer 282 3011 Field Trips Coordinator Jenny Bounds 288 7802 (mobile 014 63 5249) Gang Gang, Editor Harvey Perkins 231 8209 Garden Bird Survey, Coordinator Philip Veerman 231 4041 Hotline Ian Fraser Librarian Chris Curry 253 2306 Meetings, Talks Coordinator Barbara Allan 254 6520 (Continued inside back cover) OBSERVATIONS OF A BREEDING COLONY OF FOUR PAIRS OF REGENT HONEYEATERS AT NORTH WATSON, CANBERRA, IN 1995-96 Jenny Bounds, Muriel Brookfield and Murray Delahoy In the spring of 1995 there was a flush of sightings of Regent Honeyeaters Xanthomyza phrygia reported on the Canberra Ornithologists' Group Hotline from five different sites in and around Canberra. -

Amytornis Observations on the Foraging Ecology Of

Amytornis 19 WESTER A USTRALIA J OURAL OF O RITHOLOGY Volume 3 (2011) 19-29 ARTICLE Observations on the foraging ecology of honeyeaters (Meliphagidae) at Dryandra Woodland, Western Australia Harry F. Recher 1, 2, 3* and William E. Davis Jr. 4 1 School of Natural Sciences, Edith Cowan University, Joondalup, Western Australia, Australia 6027 2 The Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia 2000 3 Current address; P.O. Box 154, Brooklyn, New South Wales, Australia 2083 4 Boston University, 23 Knollwood Drive, East Falmouth, MA 02536, USA * Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. Dryandra Woodland, a Class A conservation reserve, on the western edge of the Western Australian wheatbelt lacks the large congregations of nectar-feeding birds associated with eucalypt woodlands to the north and east of the wheatbelt. Reasons for this are not clear, but the most productive woodlands (Wandoo Eucalyptus wandoo ) at Dryandra are dominated by Yellow-plumed Honeyeaters ( Lichenostomus ornatus ), which exclude smaller honeyeaters from their colonies. There is also comparatively little eucalypt blossom available to nectar- feeders during winter and spring when we conducted our research at Dryandra. During winter and spring, honey- eaters are dependent on small areas of shrublands dominated by species of Dryandra (Proteaceae), with species segregated by size; the smaller species making greater use of the small inflorescences of D. sessilis and D. ar- mata , while the large wattlebirds used the large inflorescences of D. nobilis . Honeyeaters at Dryandra also use other energy-rich sources of carbohydrates, such as lerp and honeydew, and take arthropods, segregating by habi- tat, foraging behaviour, and substrate. -

Or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds

Text extracted from Gill B.J.; Bell, B.D.; Chambers, G.K.; Medway, D.G.; Palma, R.L.; Scofield, R.P.; Tennyson, A.J.D.; Worthy, T.H. 2010. Checklist of the birds of New Zealand, Norfolk and Macquarie Islands, and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. 4th edition. Wellington, Te Papa Press and Ornithological Society of New Zealand. Pages 275, 279-280, 288 & 291-292. Order PASSERIFORMES: Passerine (Perching) Birds See Christidis & Boles (2008) for a review of recent studies relevant to the higher-level systematics of the passerine birds. Suborder PASSERES (or POLYMYODI): Oscines (Songbirds) The arrangement of songbirds in the 1970 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1970) was based on the premise that the species endemic to the Australasian region were derived directly from Eurasian groups and belonged in Old World families (e.g. Gerygone and Petroica in Muscicapidae). The 1990 Checklist (Checklist Committee 1990) followed the Australian lead in allocating various native songbirds to their own Australasian families (e.g. Gerygone to Acanthizidae, and Petroica to Eopsaltriidae), but the sequence was still based largely on the old Peters-Mayr arrangement. Since the late 1980s, when the 1990 Checklist was finalised, evidence from molecular biology, especially DNA studies, has shown that most of the Australian and New Zealand endemic songbirds are the product of a major Australasian radiation parallel to the radiation of songbirds in Eurasia and elsewhere. Many superficial morphological and ecological similarities between Australasian and Eurasian songbirds are the result of convergent evolution. Sibley & Ahlquist (1985, 1990) and Sibley et al. (1988) recognised a division of the songbirds into two groups which were called Corvida and Passerida (Sibley & Ahlquist 1990).