The Molecular Evolution of Feathers with Direct Evidence from Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LETTER Doi:10.1038/Nature14423

LETTER doi:10.1038/nature14423 A bizarre Jurassic maniraptoran theropod with preserved evidence of membranous wings Xing Xu1,2*, Xiaoting Zheng1,3*, Corwin Sullivan2, Xiaoli Wang1, Lida Xing4, Yan Wang1, Xiaomei Zhang3, Jingmai K. O’Connor2, Fucheng Zhang2 & Yanhong Pan5 The wings of birds and their closest theropod relatives share a ratios are 1.16 and 1.08, respectively, compared to 0.96 and 0.78 in uniform fundamental architecture, with pinnate flight feathers Epidendrosaurus and 0.79 and 0.66 in Epidexipteryx), an extremely as the key component1–3. Here we report a new scansoriopterygid short humeral deltopectoral crest, and a long rod-like bone articu- theropod, Yi qi gen. et sp. nov., based on a new specimen from the lating with the wrist. Middle–Upper Jurassic period Tiaojishan Formation of Hebei Key osteological features are as follows. STM 31-2 (Fig. 1) is inferred Province, China4. Yi is nested phylogenetically among winged ther- to be an adult on the basis of the closed neurocentral sutures of the opods but has large stiff filamentous feathers of an unusual type on visible vertebrae, although this is not a universal criterion for maturity both the forelimb and hindlimb. However, the filamentous feath- across archosaurian taxa12. Its body mass is estimated to be approxi- ers of Yi resemble pinnate feathers in bearing morphologically mately 380 g, using an empirical equation13. diverse melanosomes5. Most surprisingly, Yi has a long rod-like The skull and mandible are similar to those of other scansoriopter- bone extending from each wrist, and patches of membranous tissue ygids, and to a lesser degree to those of oviraptorosaurs and some basal preserved between the rod-like bones and the manual digits. -

Review REVIEW 1: 543–559, 2014 Doi: 10.1093/Nsr/Nwu055 Advance Access Publication 5 September 2014

National Science Review REVIEW 1: 543–559, 2014 doi: 10.1093/nsr/nwu055 Advance access publication 5 September 2014 GEOSCIENCES Special Topic: Paleontology in China The Jehol Biota, an Early Cretaceous terrestrial Lagerstatte:¨ new discoveries and implications Zhonghe Zhou ABSTRACT The study of the Early Cretaceous terrestrial Jehol Biota, which provides a rare window for reconstruction of a Lower Cretaceous terrestrial ecosystem, is reviewed with a focus on some of the latest progress. A newly proposed definition of the biota based on paleoecology and taphonomy is accepted. Although theJehol fossils are mainly preserved in two types of sedimentary rocks, there are various types of preservation with a complex mechanism that remains to be understood. New discoveries of significant taxa from the Jehol Biota, with an updated introduction of its diversity, confirm that the Jehol Biota represents one of themost diversified biotas of the Mesozoic. The evolutionary significance of major biological groups (e.g. dinosaurs, birds, mammals, pterosaurs, insects, and plants) is discussed mainly in the light of recent discoveries, and some of the most remarkable aspects of the biota are highlighted. The global and local geological, paleogeographic, and paleoenvironmental background of the Jehol Biota have contributed to the unique composition, evolution, and preservation of the biota, demonstrating widespread faunal exchanges between Asia and other continents caused by the presence of the Eurasia–North American continental mass and its link to South America, and confirming northeastern China as the origin and diversification center fora variety of Cretaceous biological groups. Although some progress has been made on the reconstruction of the paleotemperature at the time of the Jehol Biota, much more work is needed to confirm a possible link between the remarkable diversity of the biota and the cold intervals during the Early Cretaceous. -

Magnificent Magpie Colours by Feathers with Layers of Hollow Melanosomes Doekele G

© 2018. Published by The Company of Biologists Ltd | Journal of Experimental Biology (2018) 221, jeb174656. doi:10.1242/jeb.174656 RESEARCH ARTICLE Magnificent magpie colours by feathers with layers of hollow melanosomes Doekele G. Stavenga1,*, Hein L. Leertouwer1 and Bodo D. Wilts2 ABSTRACT absorption coefficient throughout the visible wavelength range, The blue secondary and purple-to-green tail feathers of magpies are resulting in a higher refractive index (RI) than that of the structurally coloured owing to stacks of hollow, air-containing surrounding keratin. By arranging melanosomes in the feather melanosomes embedded in the keratin matrix of the barbules. barbules in more or less regular patterns with nanosized dimensions, We investigated the spectral and spatial reflection characteristics of vivid iridescent colours are created due to constructive interference the feathers by applying (micro)spectrophotometry and imaging in a restricted wavelength range (Durrer, 1977; Prum, 2006). scatterometry. To interpret the spectral data, we performed optical The melanosomes come in many different shapes and forms, and modelling, applying the finite-difference time domain (FDTD) method their spatial arrangement is similarly diverse (Prum, 2006). This has as well as an effective media approach, treating the melanosome been shown in impressive detail by Durrer (1977), who performed stacks as multi-layers with effective refractive indices dependent on extensive transmission electron microscopy of the feather barbules the component media. The differently coloured magpie feathers are of numerous bird species. He interpreted the observed structural realised by adjusting the melanosome size, with the diameter of the colours to be created by regularly ordered melanosome stacks acting melanosomes as well as their hollowness being the most sensitive as optical multi-layers. -

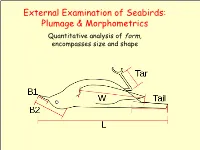

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics

External Examination of Seabirds: Plumage & Morphometrics Quantitative analysis of form, encompasses size and shape Seabird Topography ➢ Naming Conventions: • Parts of the body • Types of feathers (Harrison 1983) Types of Feathers Coverts: Rows bordering and overlaying the edges of the tail and wings on both the lower and upper sides of the body. Help streamline shape of the wings and tail and provide the bird with insulation. Feather Tracks ➢ Feathers are not attached randomly. • They occur in linear tracts called pterylae. • Spaces on bird's body without feather tracts are called apteria. • Densest area for feather tracks is head and neck. • Feathers arranged in distinct layers: contour feathers overlay down. Generic Pterylae Types of Feathers Contour feathers: outermost feathers. Define the color and shape of the bird. Contour feathers lie on top of each other, like shingles on a roof. Shed water, keeping body dry and insulated. Each contour feather controlled by specialized muscles which control their position, allowing the bird to keep the feathers in clean and neat condition. Specialized contour feathers used for flight: delineate outline of wings and tail. Types of Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Define outline of wings and tail Long and stiff Asymmetrical those on wings are called remiges (singular remex) those on tail are called retrices (singular retrix) Types of Flight Feathers Remiges: Largest contour feathers (primaries / secondaries) Responsible for supporting bird during flight. Attached by ligaments or directly to the wing bone. Types of Flight Feathers Flight feathers – special contour feathers Rectrices: tail feathers provide flight stability and control. Connected to each other by ligaments, with only the inner- most feathers attached to bone. -

Colour De Verre Molds: Feather

REUSABLE MOLDS FOR GLASS CASTING With either product, clean the See our website’s Learn section for mold with a stiff nylon brush and/ more instructions about priming or toothbrush to remove any old Colour de Verre molds with ZYP. kiln wash or boron nitride. (This step can be skipped if the mold is Filling the Feather brand new.) The suggested fill weight for the Feather is 330 to 340 grams. The If you are using Hotline Primo most simple way to fill the Feather Primer, mix the product according mold is to weigh out 330 of fine to directions. Apply the Primo frit and to evenly distribute the frit Primer™ with a soft artist’s brush in the mold. Fire the mold and frit (not a hake brush) and use a hair according the Casting Schedule Feather dryer to completely dry the coat. below. This design is also a perfect Create feathers that are as fanci- Give the mold four to five thin, candidate for our Wafer-Thin ful or realistic as you like with even coats drying each coat with a technique. One can read more Colour de Verre’s Feather de- hair dryer before applying the about this at www.colourdeverre.- sign. Once feathers are cast, next. Make sure to keep the Primo they can be slumped into amaz- com/go/wafer. ing decorative or functional well stirred as it settles quickly. pieces. The mold should be totally dry before filling. There is no reason to nnn pre-fire the mold. To use ZYP, hold the can 10 to 12 Feathers are a design element that inches from the mold. -

Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight

Feathered Dinosaurs and the Origin of Flight Exhibition Organized and Circulated by: The Dinosaur Museum, Utah The Fossil Administration Office, Liaoning, China Beipiao City Paleontological Research Center, Liaoning, China THE PREHISTORIC WORLD OF LIAONING The fossils of Liaoning represent a complex ecosystem creating a more complete picture of this particular age of dinosaurs than ever before. Life of the Early Cretaceous, 120 million years ago, was far more than a world of dinosaurs. The fossils include a remarkable variety of plants, crustaceans, insects, fish, amphibians, lizards, crocodiles, aquatic reptiles, flying reptiles, as well as birds that could fly and others which were flightless. FEATHERS BEFORE BIRDS Included are graphics and photos which show developmental stages of feathers. The fossil of the flying reptile, Pterorhynchus is preserved with details of what pterosaurs looked like which have never been seen before. The body is covered with down-like feathers which resemble those also found on the dinosaur, Sinosauropteryx. Because feathers are now known to exist on animals other than birds, this discovery changes the definition of what a bird is. Pterorhynchus Sinosauropteryx FLYING DROMAEOSAURS AND THE MISTAKEN IDENTITY Dromaeosaurs have been thought to be ground-dwelling dinosaurs that represented ancestral stages of how birds evolved. Fossils in this exhibit show that they have been misinterpreted as dinosaurs when they are actually birds. Feather impressions reveal that they had flight feathers on the wings and a second set on the hind legs. Even without the feathers preserved, the avian characteristics of the skeleton demonstrate that these dromaeosaurs are birds. This discovery means that the larger dromaeosaurs, like Deinonychus and Velociraptor of “Jurassic Park” fame, were really feathered and are secondarily flightless birds. -

Additional Specimen of Microraptor Provides Unique Evidence of Dinosaurs Preying on Birds

Additional specimen of Microraptor provides unique evidence of dinosaurs preying on birds Jingmai O’Connor1, Zhonghe Zhou1, and Xing Xu Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China Contributed by Zhonghe Zhou, October 28, 2011 (sent for review September 13, 2011) Preserved indicators of diet are extremely rare in the fossil record; The vertebral column of this specimen is complete except for even more so is unequivocal direct evidence for predator–prey its proximal and distal ends; pleurocoels are absent from the relationships. Here, we report on a unique specimen of the small thoracic vertebrae, as in dromaeosaurids and basal birds. Poor nonavian theropod Microraptor gui from the Early Cretaceous preservation prevents clear observation of sutures; however, Jehol biota, China, which has the remains of an adult enantiorni- there does not appear to be any separation between the neural thine bird preserved in its abdomen, most likely not scavenged, arches and vertebral centra, or any other indicators that the but captured and consumed by the dinosaur. We provide direct specimen is a juvenile. The number of caudal vertebrae cannot evidence for the dietary preferences of Microraptor and a nonavian be estimated, but the elongate distal caudals are tightly bounded dinosaur feeding on a bird. Further, because Jehol enantiorni- by elongated zygapophyses, as in other dromaeosaurids. The rib thines were distinctly arboreal, in contrast to their cursorial orni- cage is nearly completely preserved; both right and left sides are thurine counterparts, this fossil suggests that Microraptor hunted visible ventrally closed by the articulated gastral basket. -

Feather Loss and Feather Destructive Behavior in Pet Birds

REVIEW FEATHER LOSS AND FEATHER DESTRUCTIVE BEHAVIOR IN PET BIRDS Jonathan Rubinstein, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian), and Teresa Lightfoot, DVM, Dip. ABVP (Avian) Abstract Feather loss in psittacine birds is an extremely common and extremely frustrating clinical presentation. Causes include medical and non-medical causes of feather loss both with and without overt feather destructive behavior. Underlying causes are myriad and include inappropriate husbandry and housing; parasitic, viral and bacterial infections; metabolic and allergic diseases; and behavioral disorders. Prior to a diagnosis of a behavioral disorder, medical causes of feather loss must be excluded through a complete medical work-up including a comprehensive history, physical exam, and diagnostic testing as indicated by the history, signalment and clinical signs. This article focuses on some of the more common medical and non-medical causes of feather loss and feather destructive behavior as well as approaches to diagnosis and treatment. Copyright 2012 Published by Elsevier Inc. Key words: feather destructive behavior; psittacine; behavioral disorder; feather-picking; avian behavior eather loss is one of the more common and frustrating reasons that avian patients are presented to veterinary hospitals. Several factors make the treatment of feather loss difficult. The initial problem lies in the relative scarcity of controlled studies related to the underlying causes of feather loss in companion avian species and the paucity of current veterinary medical knowledge regarding feather loss and feather destructive behavior (FDB). Although many medical and environmental conditions Fhave been associated with FDB, few have been proven to be causal. Wherever possible, this article references applicable controlled studies, although they are few. -

Avian Feathers Function, Structure & Coloration

A Feather from the Whippoorwill (Emily Dickinson, 1955) A feather from the Whippoorwill That everlasting -- sings! Whose galleries -- are Sunrise – Whose Opera -- the Springs – Whose Emerald Nest the Ages spin Of mellow -- murmuring thread – Whose Beryl Egg, what Schoolboys hunt In "Recess" -- Overhead! Photograph by Robert Clark—Audubon Magazine 2012 Avian Feathers Function, Structure & Coloration • Tremendous Investment – 25,000 on Tundra Swan – 2-4,000 on songbirds – 970 on hummingbird • Feather Mass=2-3X Skeletal Mass • 91% Protein (keratin) 1% Fat, 8% water • Waxy secretions and fatty acids from uropygial gland protect feathers Feather Outline • Functions in addition • Coloration to flight – Pigments – Structural Colors • Structure & Variation • Origin of feather color and recent fossil discoveries Do feathers have a function or are they just an expensive costume? • Insulation • Sound production • Sound capture • Camouflage • Aerodynamics • Sexual selection • Protection • Nesting, diet, other Diverse Functions • Crypticity – Disruptive color patterns in Killdeer and meadowlarks – Mimicry in bitterns, snipe, and woodcock Diverse Functions • Sound production for attraction – Booming of Ruffed Grouse wings – Primary flight feathers of American Woodcock – Hummingbirds • You Tube Hummingbird Music – Manakins • Manakin Wing Sound Diverse Functions • Sound gathering properties of owls and some hawks – Eastern Screech Owl – Northern Harrier (hawk) http://www.wisenaturephotos.com/NEW!!!%202-10-06.htm Diverse Functions • Support – Tail rectrices -

Pattern and Chronology of Prebasic Molt for the Wood Thrush and Its Relation to Reproduction and Migration Departure

Wilson Bull., 110(3), 1998, pp. 384-392 PATTERN AND CHRONOLOGY OF PREBASIC MOLT FOR THE WOOD THRUSH AND ITS RELATION TO REPRODUCTION AND MIGRATION DEPARTURE J. H. VEGA RIVERA,1,3 W. J. MCSHEA,* J. H. RAPPOLE, AND C. A. HAAS ’ ABSTRACT-Documentation of the schedule and pattern of molt and their relation to reproduction and migration departure are important, but often neglected, areas of knowledge. We radio-tagged Wood Thrushes (Hylocichlu mustelina), and monitored their movements and behavior on the U.S. Marine Corps Base, Quantico, Virginia (38” 40 ’ N, 77” 30 ’ W) from May-Oct. of 1993-1995. The molt period in adults extended from late July to early October. Molt of flight feathers lasted an average of 38 days (n = 17 birds) and there was no significant difference in duration between sexes. In 21 observed and captured individuals, all the rectrices were lost simultaneously or nearly so, and some individuals dropped several primaries over a few days. Extensive molt in Wood Thrushes apparently impaired flight efficiency, and birds at this stage were remarkably cautious and difficult to capture and observe. All breeding individuals were observed molting l-4 days after fledgling independence or last-clutch predation, except for one pair that began molt while still caring for fledglings. Our data indicate that energetics or flight efficiency constraints may dictate a separation of molt and migration. We did not observe Wood Thrushes leaving the Marine Base before completion of flight-feather molt. Departure of individuals with molt in body and head, however, was common. We caution against interpreting the lack of observations or captures of molting individuals on breeding sites as evidence that birds actually have left the area. -

The Oldest Record of Ornithuromorpha from the Early Cretaceous of China

ARTICLE Received 6 Jan 2015 | Accepted 20 Mar 2015 | Published 5 May 2015 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms7987 OPEN The oldest record of ornithuromorpha from the early cretaceous of China Min Wang1, Xiaoting Zheng2,3, Jingmai K. O’Connor1, Graeme T. Lloyd4, Xiaoli Wang2,3, Yan Wang2,3, Xiaomei Zhang2,3 & Zhonghe Zhou1 Ornithuromorpha is the most inclusive clade containing extant birds but not the Mesozoic Enantiornithes. The early evolutionary history of this avian clade has been advanced with recent discoveries from Cretaceous deposits, indicating that Ornithuromorpha and Enantiornithes are the two major avian groups in Mesozoic. Here we report on a new ornithuromorph bird, Archaeornithura meemannae gen. et sp. nov., from the second oldest avian-bearing deposits (130.7 Ma) in the world. The new taxon is referable to the Hongshanornithidae and constitutes the oldest record of the Ornithuromorpha. However, A. meemannae shows few primitive features relative to younger hongshanornithids and is deeply nested within the Hongshanornithidae, suggesting that this clade is already well established. The new discovery extends the record of Ornithuromorpha by five to six million years, which in turn pushes back the divergence times of early avian lingeages into the Early Cretaceous. 1 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100044, China. 2 Institue of Geology and Paleontology, Linyi University, Linyi, Shandong 276000, China. 3 Tianyu Natural History Museum of Shandong, Pingyi, Shandong 273300, China. 4 Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Science, Macquarie University, Sydney, New South Wales 2019, Australia. -

The Physical Structure, Optical Mechanics and Aesthetics of the Peacock Tail Feathers

© 2002 WIT Press, Ashurst Lodge, Southampton, SO40 7AA, UK. All rights reserved. Web: www.witpress.com Email [email protected] Paper from: Design and Nature, CA Brebbia, L Sucharov & P Pascola (Editors). ISBN 1-85312-901-1 The physical structure, optical mechanics and aesthetics of the peacock tail feathers S.C. Burgess Department of Mechanical Engineering, University of Bristol, University Walk, Bristol, BS8 I TR, UK Abstract The peacock tail feathers have no flight or thermal function but have the sole purpose of providing an attractive display. The peacock tail produces colours by thin-film interference. There is a very high level of optimum design in the peacock feathers including optimum layer thickness, multi layers, precision co- ordination and dark background colour, This paper analyses the structure and beauty of the peacock tail. 1 Introduction Aesthetic beauty in appearance is produced by attributes such as patterns, brightness, variety, curves, blending or any combination of such attributes. Beauty is so important in engineering design that there is a whole subject called aesthetics which defines how beauty can be added to man-made products’, An object can have two types of beauty: inherent beauty and added beauty, Inherent beauty is a beauty that exists as a hi-product of mechanical design, In contrast, added beauty is a type of beauty which has the sole purpose of providing a beautiful display. These two types of beauty can be seen in man-made products like buildings and bridges. An example of inherent beauty is found in the shape of a suspension bridge, A suspension bridge has a curved cable structure because this is an efficient way of supporting a roadway.