The Origin and Diversification of Birds

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beyond Endocasts: Using Predicted Brain-Structure Volumes of Extinct Birds to Assess Neuroanatomical and Behavioral Inferences

diversity Article Beyond Endocasts: Using Predicted Brain-Structure Volumes of Extinct Birds to Assess Neuroanatomical and Behavioral Inferences 1, , 2 2 Catherine M. Early * y , Ryan C. Ridgely and Lawrence M. Witmer 1 Department of Biological Sciences, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA 2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701, USA; [email protected] (R.C.R.); [email protected] (L.M.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Current Address: Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL 32611, USA. y Received: 1 November 2019; Accepted: 30 December 2019; Published: 17 January 2020 Abstract: The shape of the brain influences skull morphology in birds, and both traits are driven by phylogenetic and functional constraints. Studies on avian cranial and neuroanatomical evolution are strengthened by data on extinct birds, but complete, 3D-preserved vertebrate brains are not known from the fossil record, so brain endocasts often serve as proxies. Recent work on extant birds shows that the Wulst and optic lobe faithfully represent the size of their underlying brain structures, both of which are involved in avian visual pathways. The endocasts of seven extinct birds were generated from microCT scans of their skulls to add to an existing sample of endocasts of extant birds, and the surface areas of their Wulsts and optic lobes were measured. A phylogenetic prediction method based on Bayesian inference was used to calculate the volumes of the brain structures of these extinct birds based on the surface areas of their overlying endocast structures. This analysis resulted in hyperpallium volumes of five of these extinct birds and optic tectum volumes of all seven extinct birds. -

MADAGASCAR: the Wonders of the “8Th Continent” a Tropical Birding Custom Trip

MADAGASCAR: The Wonders of the “8th Continent” A Tropical Birding Custom Trip October 20—November 6, 2016 Guide: Ken Behrens All photos taken during this trip by Ken Behrens Annotated bird list by Jerry Connolly TOUR SUMMARY Madagascar has long been a core destination for Tropical Birding, and with the opening of a satellite office in the country several years ago, we further solidified our expertise in the “Eighth Continent.” This custom trip followed an itinerary similar to that of our main set-departure tour. Although this trip had a definite bird bias, it was really a general natural history tour. We took our time in observing and photographing whatever we could find, from lemurs to chameleons to bizarre invertebrates. Madagascar is rich in wonderful birds, and we enjoyed these to the fullest. But its mammals, reptiles, amphibians, and insects are just as wondrous and accessible, and a trip that ignored them would be sorely missing out. We also took time to enjoy the cultural riches of Madagascar, the small villages full of smiling children, the zebu carts which seem straight out of the Middle Ages, and the ingeniously engineered rice paddies. If you want to come to Madagascar and see it all… come with Tropical Birding! Madagascar is well known to pose some logistical challenges, especially in the form of the national airline Air Madagascar, but we enjoyed perfectly smooth sailing on this tour. We stayed in the most comfortable hotels available at each stop on the itinerary, including some that have just recently opened, and savored some remarkably good food, which many people rank as the best Madagascar Custom Tour October 20-November 6, 2016 they have ever had on any birding tour. -

Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes Fulgens Donald R

Digital Commons @ George Fox University Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Department of Biology and Chemistry Chemistry 6-27-2018 Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens Donald R. Powers George Fox University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, and the Poultry or Avian Science Commons Recommended Citation Powers, Donald R., "Rivoli's Hummingbird: Eugenes fulgens" (2018). Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry. 123. https://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/bio_fac/123 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Biology and Chemistry at Digital Commons @ George Fox University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications - Department of Biology and Chemistry by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ George Fox University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rivoli's Hummingbird Eugenes fulgens Order: CAPRIMULGIFORMES Family: TROCHILIDAE Version: 2.1 — Published June 27, 2018 Donald R. Powers Introduction Rivoli's Hummingbird was named in honor of the Duke of Rivoli when the species was described by René Lesson in 1829 (1). Even when it became known that William Swainson had written an earlier description of this species in 1827, the common name Rivoli's Hummingbird remained until the early 1980s, when it was changed to Magnificent Hummingbird. In 2017, however, the name was restored to Rivoli's Hummingbird when the American Ornithological Society officially recognized Eugenes fulgens as a distinct species from E. spectabilis, the Talamanca Hummingbird, of the highlands of Costa Rica and western Panama (2). See Systematics: Related Species. -

Tiny Fossil Sheds Light on Miniaturization of Birds

Retraction Tiny fossil sheds light on miniaturization of birds Roger B. J. Benson Nature 579, 199–200 (2020) In view of the fact that the authors of ‘Hummingbird-sized dinosaur from the Cretaceous period of Myanmar‘ (L. Xing et al. Nature 579, 245–249; 2020) are retracting their report, I wish to retract this News & Views article, which dealt with this study and was based on the accuracy and reproducibility of their data. Nature | 22 July 2020 ©2020 Spri nger Nature Li mited. All rights reserved. drives the assembly of DNA-PK and stimulates regulation of protein synthesis. And, although 3. Dragon, F. et al. Nature 417, 967–970 (2002). its catalytic activity in vitro, although does so further studies are required, we might have 4. Adelmant, G. et al. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 11, 411–421 (2012). much less efficiently than can DNA. taken a step closer to deciphering the 5. Britton, S., Coates, J. & Jackson, S. P. J. Cell Biol. 202, Taken together, these observations suggest mysterious ribosomopathies. 579–595 (2013). a model in which KU recruits DNA-PKcs to the 6. Barandun, J. et al. Nature Struct. Mol. Biol. 24, 944–953 (2017). small-subunit processome. In the case of Alan J. Warren is at the Cambridge Institute 7. Ma, Y. et al. Cell 108, 781–794 (2002). kinase-defective DNA-PK, the mutant enzyme’s for Medical Research, Hills Road, Cambridge 8. Yin, X. et al. Cell Res. 27, 1341–1350 (2017). inability to regulate its own activity gives the CB2 OXY, UK. 9. Sharif, H. et al. -

Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds

Evol Biol DOI 10.1007/s11692-015-9334-7 SYNTHESIS PAPER Altriciality and the Evolution of Toe Orientation in Birds 1 1 1 Joa˜o Francisco Botelho • Daniel Smith-Paredes • Alexander O. Vargas Received: 3 November 2014 / Accepted: 18 June 2015 Ó Springer Science+Business Media New York 2015 Abstract Specialized morphologies of bird feet have trees, to swim under and above the water surface, to hunt and evolved several times independently as different groups have fish, and to walk in the mud and over aquatic vegetation, become zygodactyl, semi-zygodactyl, heterodactyl, pam- among other abilities. Toe orientations in the foot can be prodactyl or syndactyl. Birds have also convergently described in six main types: Anisodactyl feet have digit II evolved similar modes of development, in a spectrum that (dII), digit III (dIII) and digit IV (dIV) pointing forward and goes from precocial to altricial. Using the new context pro- digit I (dI) pointing backward. From the basal anisodactyl vided by recent molecular phylogenies, we compared the condition four feet types have arisen by modifications in the evolution of foot morphology and modes of development orientation of digits. Zygodactyl feet have dI and dIV ori- among extant avian families. Variations in the arrangement ented backward and dII and dIII oriented forward, a condi- of toes with respect to the anisodactyl ancestral condition tion similar to heterodactyl feet, which have dI and dII have occurred only in altricial groups. Those groups repre- oriented backward and dIII and dIV oriented forward. Semi- sent four independent events of super-altriciality and many zygodactyl birds can assume a facultative zygodactyl or independent transformations of toe arrangements (at least almost zygodactyl orientation. -

P0455-P0459.Pdf

The Condor 101:455-459 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1999 BOOK REVIEWS Social Influences on Vocal Development.- Why read the rest of the book if the main themes Charles T Snowdon and Mat-tine Hausberger, eds. are already discussed in the introduction? I believe it 1997. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, U.K. is worth it, not only to check the statements of the ix + 351 pp. ISBN 0521 49526 1. $95.00 (cloth). editors. All the articles are fine reviews of a given At least in certain aspects, this book is a referee’s field, written by experts. Doug Nelson provides a very dream: not only do the editors provide short summaries good account of the state of the art in song learning in their introduction of the 16 articles making up this theory, and as I expressed above, I fully agree with his volume, they also inform the reader about the main claim that the two stage nature of song learning is still general conclusions that can be drawn from those ar- not fully understood or accepted by other researchers ticles. According to Snowdon and Hausberger, there of the field. are five central themes that arc treated in almost all Luis Baptista and Sandra Gaunt provide a very com- contributions. The first and main theme is the claim petent review on social interaction and vocal devel- that vocal learning has more aspects than learning to opment in birds. As ever, there is a wealth of findings produce sounds. It is also necessary to learn how to from the lab and from the field included in their re- use and comprehend vocalizations. -

A New Raptorial Dinosaur with Exceptionally Long Feathering Provides Insights Into Dromaeosaurid flight Performance

ARTICLE Received 11 Apr 2014 | Accepted 11 Jun 2014 | Published 15 Jul 2014 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5382 A new raptorial dinosaur with exceptionally long feathering provides insights into dromaeosaurid flight performance Gang Han1, Luis M. Chiappe2, Shu-An Ji1,3, Michael Habib4, Alan H. Turner5, Anusuya Chinsamy6, Xueling Liu1 & Lizhuo Han1 Microraptorines are a group of predatory dromaeosaurid theropod dinosaurs with aero- dynamic capacity. These close relatives of birds are essential for testing hypotheses explaining the origin and early evolution of avian flight. Here we describe a new ‘four-winged’ microraptorine, Changyuraptor yangi, from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota of China. With tail feathers that are nearly 30 cm long, roughly 30% the length of the skeleton, the new fossil possesses the longest known feathers for any non-avian dinosaur. Furthermore, it is the largest theropod with long, pennaceous feathers attached to the lower hind limbs (that is, ‘hindwings’). The lengthy feathered tail of the new fossil provides insight into the flight performance of microraptorines and how they may have maintained aerial competency at larger body sizes. We demonstrate how the low-aspect-ratio tail of the new fossil would have acted as a pitch control structure reducing descent speed and thus playing a key role in landing. 1 Paleontological Center, Bohai University, 19 Keji Road, New Shongshan District, Jinzhou, Liaoning Province 121013, China. 2 Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90007, USA. 3 Institute of Geology, Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences, 26 Baiwanzhuang Road, Beijing 100037, China. 4 University of Southern California, Health Sciences Campus, BMT 403, Mail Code 9112, Los Angeles, California 90089, USA. -

Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor How They Arise, Modify and Vanish

Fascinating Life Sciences Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Fascinating Life Sciences This interdisciplinary series brings together the most essential and captivating topics in the life sciences. They range from the plant sciences to zoology, from the microbiome to macrobiome, and from basic biology to biotechnology. The series not only highlights fascinating research; it also discusses major challenges associated with the life sciences and related disciplines and outlines future research directions. Individual volumes provide in-depth information, are richly illustrated with photographs, illustrations, and maps, and feature suggestions for further reading or glossaries where appropriate. Interested researchers in all areas of the life sciences, as well as biology enthusiasts, will find the series’ interdisciplinary focus and highly readable volumes especially appealing. More information about this series at http://www.springer.com/series/15408 Dieter Thomas Tietze Editor Bird Species How They Arise, Modify and Vanish Editor Dieter Thomas Tietze Natural History Museum Basel Basel, Switzerland ISSN 2509-6745 ISSN 2509-6753 (electronic) Fascinating Life Sciences ISBN 978-3-319-91688-0 ISBN 978-3-319-91689-7 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-91689-7 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018948152 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2018. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

R~;: PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL

....----------- 'r~;: i ! 'r; Pa/eont .. 62(4), 1988, pp. 64~52 Copyright © 1988, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/88/0062-0640$03.00 PHYSIOLOGICAL, MIGRATORIAL, CLIMATOLOGICAL, GEOPHYSICAL, SURVIVAL, AND EVOLUTIONARY IMPLICATIONS OF CRETACEOUS POLAR DINOSAURS GREGORY S. PAUL 3109 North Calvert Street, Baltimore, Maryland 21218 ABSTRACTT- he presence of Late Cretaceous social dinosaurs in polar regions confronted them with winter conditions of extended dark, coolness, breezes, and precipitation that could best be coped with via an endothermic homeothermic physiology of at least the tenrec level. This is true whether the dinosaurs stayed year round in the polar regime-which in North America extended from Alaska south to Montana-or if they migrated away from polar winters. More reptilian physiologies fail to meet the demands of such winters -in certain key ways, a· point tentatively confirmed by the apparent failure of giant Late Cretaceous phobosuchid crocodilians to dwell north of Montana. Low metabolisms were also insufficient for extended annual migrations away from and towards the poles. It is shown that even high metabolic rate dinosaurs probably remained in their polar habitats year-round. The possibility that dinosaurs had avian-mammalian metabolic systems, and may have borne insulation at least seasonally, severely limits their use as polar paleoclimatic and Earth axial tilt indicators. Polar dinosaurs may have been a center of dinosaur evolution. The possible ability of polar dinosaurs to cope with conditions of cool and dark challenges theories that a gradual temperature decline, or a sudden, meteoritic or volcanic induced collapse in temperature and sunlight, destroyed the dinosaurs. INTRODUCTION America suggests that dinosaurs were regularly crossing, and NCREASINGNUMBERSof remains show that dinosaurs lived living upon, the Bering Land Bridge within a few degrees of the I near the North and South Poles during the Cretaceous. -

State of the Palaeoart

Palaeontologia Electronica http://palaeo-electronica.org State of the Palaeoart Mark P. Witton, Darren Naish, and John Conway The discipline of palaeoart, a branch of natural history art dedicated to the recon- struction of extinct life, is an established and important component of palaeontological science and outreach. For more than 200 years, palaeoartistry has worked closely with palaeontological science and has always been integral to the enduring popularity of prehistoric animals with the public. Indeed, the perceived value or success of such products as popular books, movies, documentaries, and museum installations can often be linked to the quality and panache of its palaeoart more than anything else. For all its significance, the palaeoart industry ment part of this dialogue in the published is often poorly treated by the academic, media and literature, in turn bringing the issues concerned to educational industries associated with it. Many wider attention. We argue that palaeoartistry is standard practises associated with palaeoart pro- both scientifically and culturally significant, and that duction are ethically and legally problematic, stifle improved working practises are required by those its scientific and cultural growth, and have a nega- involved in its production. We hope that our views tive impact on the financial viability of its creators. inspire discussion and changes sorely needed to These issues create a climate that obscures the improve the economy, quality and reputation of the many positive contributions made by palaeoartists palaeoart industry and its contributors. to science and education, while promoting and The historic, scientific and economic funding derivative, inaccurate, and sometimes exe- significance of palaeoart crable artwork. -

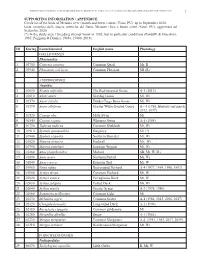

1 ID Euring Latin Binomial English Name Phenology Galliformes

BIRDS OF METAURO RIVER: A GREAT ORNITHOLOGICAL DIVERSITY IN A SMALL ITALIAN URBANIZING BIOTOPE, REQUIRING GREATER PROTECTION 1 SUPPORTING INFORMATION / APPENDICE Check list of the birds of Metauro river (mouth and lower course / Fano, PU), up to September 2020. Lista completa delle specie ornitiche del fiume Metauro (foce e basso corso /Fano, PU), aggiornata ad Settembre 2020. (*) In the study area 1 breeding attempt know in 1985, but in particolar conditions (Pandolfi & Giacchini, 1985; Poggiani & Dionisi, 1988a, 1988b, 2019). ID Euring Latin binomial English name Phenology GALLIFORMES Phasianidae 1 03700 Coturnix coturnix Common Quail Mr, B 2 03940 Phasianus colchicus Common Pheasant SB (R) ANSERIFORMES Anatidae 3 01690 Branta ruficollis The Red-breasted Goose A-1 (2012) 4 01610 Anser anser Greylag Goose Mi, Wi 5 01570 Anser fabalis Tundra/Taiga Bean Goose Mi, Wi 6 01590 Anser albifrons Greater White-fronted Goose A – 4 (1986, february and march 2012, 2017) 7 01520 Cygnus olor Mute Swan Mi 8 01540 Cygnus cygnus Whooper Swan A-1 (1984) 9 01730 Tadorna tadorna Common Shelduck Mr, Wi 10 01910 Spatula querquedula Garganey Mr (*) 11 01940 Spatula clypeata Northern Shoveler Mr, Wi 12 01820 Mareca strepera Gadwall Mr, Wi 13 01790 Mareca penelope Eurasian Wigeon Mr, Wi 14 01860 Anas platyrhynchos Mallard SB, Mr, W (R) 15 01890 Anas acuta Northern Pintail Mi, Wi 16 01840 Anas crecca Eurasian Teal Mr, W 17 01960 Netta rufina Red-crested Pochard A-4 (1977, 1994, 1996, 1997) 18 01980 Aythya ferina Common Pochard Mr, W 19 02020 Aythya nyroca Ferruginous -

Aullwood's Birds (PDF)

Aullwood's Bird List This list was collected over many years and includes birds that have been seen at or very near Aullwood. The list includes some which are seen only every other year or so, along with others that are seen year around. Ciconiiformes Great blue heron Green heron Black-crowned night heron Anseriformes Canada goose Mallard Blue-winged teal Wood duck Falconiformes Turkey vulture Osprey Sharp-shinned hawk Cooper's hawk Red-tailed hawk Red-shouldered hawk Broad-winged hawk Rough-legged hawk Marsh hawk American kestrel Galliformes Bobwhite Ring-necked pheasant Gruiformes Sandhill crane American coot Charadriformes Killdeer American woodcock Common snipe Spotted sandpiper Solitary sandpiper Ring-billed gull Columbiformes Rock dove Mourning dove Cuculiformes Yellow-billed cuckoo Strigiformes Screech owl Great horned owl Barred owl Saw-whet owl Caprimulgiformes Common nighthawk Apodiformes Chimney swift Ruby-throated hummingbird Coraciformes Belted kinghisher Piciformes Common flicker Pileated woodpecker Red-bellied woodpecker Red-headed woodpecker Yellow-bellied sapsucker Hairy woodpecker Downy woodpecker Passeriformes Eastern kingbird Great crested flycatcher Eastern phoebe Yellow-bellied flycatcher Acadian flycatcher Willow flycatcher Least flycatcher Eastern wood pewee Olive-sided flycatcher Tree swallow Bank swallow Rough-winged swallow Barn swallow Purple martin Blue jay Common crow Black-capped chickadee Carolina chickadee Tufted titmouse White-breasted nuthatch Red-breasted nuthatch Brown creeper House wren Winter wren