Porcelain Acquisitions Through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net, 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1930, Volume 25, Issue No. 1

A SC &&• 1? MARYLAND HlSTOEICAL MAGAZIISrE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXV BALTIMORE 1930 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXV. A REGISTER OP THE CABINET MAKERS AND ALLIED TRADES IN MARY- LAND AS SHOWN BY THE NEWSPAPERS AND DIRECTORIES, 1746 TO 1820. By Henry J. Berkley, M.D., 1 COLONIAL RECORDS OP WORCESTER COUNTY. Contributed iy Louis Dow Scisco, 28 DESCENDANTS OP FRANCIS CALVERT (1751-1823). By John Bailey Culvert Nicklin, ------ ---30 REV. MATTHEW HILL TO RICHARD BAXTER, 49 EXTRACTS PROM ACCOUNT AND LETTER BOOKS OP DR. CHARLES CARROLL, OP ANNAPOLIS, 53, 284 BENJAMIN HENRY LATKOBE TO DAVID ESTB, 77 PROCEEDINGS OP THE SOCIETY, ------ 78, 218, 410 NOTES, CORRECTIONS, ETC., 95, 222, 319 LIST OP MEMBERS OP THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, - - 97 SOMETHING MOKE OP THE GREAT CONPEDERATB GENERAL, " STONE- WALL " JACKSON AND ONE OP HIS HUMBLE FOLLOWERS IN THE SOUTH OF YESTERYEAR. By DeCourcy W. Thorn, - - 129 DURHAM COUNTY: LORD BALTIMORE'S ATTEMPT AT SETTLEMENT OP HIS LANDS ON THE DELAWARE BAY, 1670-1685. By Percy O. Skirven, ---------- 157 A SKETCH OP THOMAS HARWOOD ALEXANDER, CHANCERY COUNCEL- LOR OP MARYLAND, 1801-1871. By Henry J. Berkley, - - 167 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1850-1851. By L. E. Blauch, 169 THE COMMISSARY IN COLONIAL MARYLAND. By Edith E. MacQueen, 190 COLONIAL RECORDS OP FREDERICK COUNTY. Contributed by Louis Dow Sisco, 206 MARYLAND RENT ROLLS, 209 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1864. By L. E. Blauch, 225 THE ABINGTONS OF ST. MARY'S AND CALVERT COUNTIES. By Henry J. Berkley, 251 BALTIMORE COUNTY RECORDS OF 1668 AND 1669. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

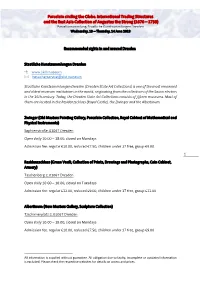

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Gemälde Galerie Alte Meister Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Gemäldegalerie Alte Gemälde Galerie Alte Meister

Museumsführer Museumsführer GEMÄLDE GALERIE ALTE MEISTER GEMÄLDEGALERIE ALTE MEISTER GEMÄLDEGALERIE ALTE GEMÄLDE GALERIE ALTE MEISTER Herausgegeben von den Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Stephan Koja Stephan Koja Eine derart groß angelegte Sammeltätigkeit war möglich, weil das Kurfürsten tum Sachsen zu den wohlhabendsten Gebieten des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deut- »Ich wurde ob der Masse des scher Nation gehörte. Reiche Vorkommen wertvoller Erze und Mineralien, die Lage am Schnittpunkt wichtiger Handelsstraßen Europas sowie ein ab dem 18. Jahrhun- Herrlichen so konfus« dert hochentwickeltes Manufakturwesen ermöglichten den Wohlstand des Landes. Die Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Neuordnung der Sammlungen unter August dem Starken 1707 ließ August der Starke die Gemäldesammlung aus den allgemeinen Beständen der Kunstkammer herauslösen und die besten Bilder in einem eigenen Raum im Schloss unterbringen. 1718 zogen sie weiter in den Redoutensaal, schließlich 1726 in den »Riesensaal« und dessen angrenzende Zimmer. Die übrigen Objekte der »Die königliche Galerie der Schildereien in Dresden enthält ohne Zweifel einen Kunstkammer bildeten den Grundstock für die anderen berühmten Sammlungen Schatz von Werken der größten Meister, der vielleicht alle Galerien in der Welt Dresdens wie das Grüne Gewölbe, die Porzellansammlung, das Kupferstich-Kabinett, übertrifft«, schrieb Johann Joachim Winckelmann 1755.1 Schon 1749 hatte er be- den Mathematisch-Physikalischen Salon oder die Skulpturensammlung. Denn schon eindruckt seinem Freund Konrad Friedrich Uden mitgeteilt: »Die Königl. Bilder um 1717 hatte August der Starke, wohl inspiriert durch dementsprechende Eindrü- Gallerie ist […] die schönste in der Welt.«2 cke auf Reisen, eine Funktionsskizze4 für die Aufteilung der Sammlung entworfen, In der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts war die Dresdner Gemäldegalerie nach der das Sammlungsgut und nicht die historische Klassifizierung das Ordnungs- bereits ein Anziehungspunkt für Künstler, Intellektuelle und kulturaffine Reisende kriterium darstellte. -

The Saber's Many Travels (The Origins of the Cross-Cutting Art)

Bartosz Sieniawski Warsaw, 4th February 2013 Janusz Sieniawski The Saber’s Many Travels (The Origins of the Cross-Cutting Art) Before you engage in combat, mind this: the blade of you saber is nothing else – and cannot be anything else – but an extension of your own arm, and equally: your entire arm, from the armpit right to the hand which is grasping the hilt, is nothing else but an extended grip of the saber. (Michał Starzewski, of the Ostoja coat of arms) Some remarks on the history of the saber: The curved saber first emerged on the steppes of Central Asia amongst the nomadic peoples. It reached the Middle East in 7th century AD via Arab traders, who had good trade relations with the nomads. A while later, the Arabs conquered the Sassanid Persian Empire and assimilated the conquered nations, which meant that the saber could spread across the region in a relatively short time, becoming an ever-present element of the Islamic world. In the 9th century saber was commonly used as a weapon by Huns, Avars, Cumans, Bulgars, Turks and Hungarians, whose influx threatened to flood Europe. Miniatures in the Byzantine chronicles of Skylitzes show bands of warriors of Turkic-Tartar origin, who inhabited the regions around the Caspian Sea, mostly Pechenges and Kipchaks, armed with spears and long sabers. In the 12th century, again thanks to the nomadic peoples, the saber was introduced in China, India and in Rus, and four hundred years later, via Turkey and Hungary, it finally arrived in Poland. It is quite unparalleled for a single weapon type to be in use by warriors, knights and soldiers on battlefields across the world and to remain almost unchanged for hundreds of years (from 5th to 20th century). -

Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762)

Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) IRENA BIEŃKOWSKA University of Warsaw Institute of Musicology Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) Musicology Today • Vol. 10 • 2013 DOI: 10.2478/muso-2014-0004 For years, Polish musicologists have looked closely at differences in the quantity and quality of stored music, musical activity at the courts of Polish nobility. These architectural monuments and works of art). efforts have resulted in numerous study papers (which A recent study by the present author of materials are mostly fragmentary in nature) analysing musical collected at the Central Archives of Historical Records ensembles active in the courts, theatrical centres, and in Warsaw (hereinafter: AGAD) has yielded new findings the playing of music by the nobles themselves. The about music at the court of Stanisław Poniatowski main problem faced by researchers is the fragmented (1676–1762), the governor of the Mazovia Province, and state of collections, or simply their non-existence. The bearer of the Ciołek family coat of arms. The Poniatowski work becomes time-consuming and arduous, and it lies Family Archive (hereinafter: ARP) section of AGAD was beyond the scope of a typical musicological research, as investigated with a view to a better understanding of the information sources are quite scattered, incomplete and musical activity at the governor’s court3. typically not primary in nature. Stanisław Poniatowski, who is considered to have Research to date into sources from 18th-century courts brought about the Poniatowski family’s rise in power, and has not been carried out in a systematic fashion, and who was the father of the future king of the Republic has only looked at individual representatives of major of Poland, came from a noble, but not particularly aristocratic families from the Republic of Poland, such as affluent family. -

O Mito De Apolo E Dafne

o mito de apolo e dafne Sobre o autor LouiS de SiLveStre (1675-1760) Louis de Silvestre nasceu em Sceaux, cidade ao sul de Paris, França, no dia 23 de junho de 1675. Filho de Israel Silvestre, pintor e gravador oficial do Delfim Luís da França. Teve suas primeiras lições de pintura com o pai, sendo depois treinado por Charles Le Brun e Bon Boullogne. Parte para Roma, a fim de terminar seus estudos, onde é acolhido por Carlo Maratta, que terá imensa influência em sua pintura. Especializa-se na pintura histórica e de retratos. Retorna a Paris em 1702, sendo aceito na Academia Real de Pintura e Escultura logo em seguida. Torna-se professor dessa instituição em 1706. Destacam-se desse período a cena bíblica do paralítico do templo e o retrato do rei francês Luís XV, de 1715, mantido na Galeria de Dresden (Duissieux, 1876). Recebe convite do príncipe Frederico Augusto da Saxônia para trabalhar em Dresden, na corte de seu pai, o rei Augusto II da Polônia.1 Silvestre aceita a oferta e recebe dispensa da corte francesa, chegando em Dresden em 1718. Tanto Augusto II, quanto seu filho, admiravam o trabalho de Silvestre sobremaneira, concedendo-lhe as maiores honras disponíveis para o artista. Foi escolhido pintor oficial da corte, depois diretor da Academia de Dresden, em 1727. O príncipe Frederico, agora Augusto III da Polônia, concede-lhe um título nobiliárquico em 1741, fazendo o mesmo com 1 Entre os séculos XVI e XVIII, a Polônia e a Lituânia formavam uma monarquia dual e eletiva, chamada de Comunidade Polaco-Lituana. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. -

Geist Und Glanz Der Dresdner Gemäldegalerie

Dresden_Umschlag_070714 15.07.14 16:23 Seite 1 Geist und Glanz der Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Rund hundert Meisterwerke berühmter Künstler, darunter Carracci, van Dyck, Velázquez, Lorrain, Watteau und Canaletto, veranschau lichen Entstehen und Charakter der legendär reichen Dresdner Gemälde - galerie in Barock und Aufklärung. Im »Augusteischen Zeitalter« der sächsischen Kurfürsten und polnischen Könige August II. (1670–1733) und August III. (1696–1763), einer Zeit der wirtschaft lichen und kultu- Dr Geis rellen Blüte, dienten zahlreiche Bauprojekte und die forcierte Entwick- esdner Gemäldegal lung der königlichen Sammlungen dazu, den neuen Machtanspruch des t und Glanz der Dresdner Hofs zu demonstrieren. Damals erhielt die Stadt mit dem Bau von Hof- und Frauenkirche ihre heute noch weltberühmte Silhouette. Renommierte Maler wie der Franzose Louis de Silvestre (1675–1760) oder der Italiener Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780) wurden als Hofkünst- ler verpflichtet. Diese lebendige und innovative Zeit bildet den Hinter- grund, vor dem die Meisterwerke ihre Geschichten erzählen. erie HIRMER WWW.HIRMERVERLAG.DE HIRMER Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 1 Rembrandt Tizian Bellotto Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 2 Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 3 Rembrandt Geist und Glanz der Tizian Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Bellotto Herausgegeben von Bernhard Maaz, Ute Christina Koch und Roger Diederen HIRMER Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:31 Seite 4 Dresden_Inhalt_070714 15.07.14 16:16 Seite 5 Inhalt 6 Grußwort 8 Vorwort Bernhard Maaz