Lagnasco / Wallenstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

Gemälde Galerie Alte Meister Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister Gemäldegalerie Alte Gemälde Galerie Alte Meister

Museumsführer Museumsführer GEMÄLDE GALERIE ALTE MEISTER GEMÄLDEGALERIE ALTE MEISTER GEMÄLDEGALERIE ALTE GEMÄLDE GALERIE ALTE MEISTER Herausgegeben von den Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Dresden, Stephan Koja Stephan Koja Eine derart groß angelegte Sammeltätigkeit war möglich, weil das Kurfürsten tum Sachsen zu den wohlhabendsten Gebieten des Heiligen Römischen Reiches Deut- »Ich wurde ob der Masse des scher Nation gehörte. Reiche Vorkommen wertvoller Erze und Mineralien, die Lage am Schnittpunkt wichtiger Handelsstraßen Europas sowie ein ab dem 18. Jahrhun- Herrlichen so konfus« dert hochentwickeltes Manufakturwesen ermöglichten den Wohlstand des Landes. Die Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Neuordnung der Sammlungen unter August dem Starken 1707 ließ August der Starke die Gemäldesammlung aus den allgemeinen Beständen der Kunstkammer herauslösen und die besten Bilder in einem eigenen Raum im Schloss unterbringen. 1718 zogen sie weiter in den Redoutensaal, schließlich 1726 in den »Riesensaal« und dessen angrenzende Zimmer. Die übrigen Objekte der »Die königliche Galerie der Schildereien in Dresden enthält ohne Zweifel einen Kunstkammer bildeten den Grundstock für die anderen berühmten Sammlungen Schatz von Werken der größten Meister, der vielleicht alle Galerien in der Welt Dresdens wie das Grüne Gewölbe, die Porzellansammlung, das Kupferstich-Kabinett, übertrifft«, schrieb Johann Joachim Winckelmann 1755.1 Schon 1749 hatte er be- den Mathematisch-Physikalischen Salon oder die Skulpturensammlung. Denn schon eindruckt seinem Freund Konrad Friedrich Uden mitgeteilt: »Die Königl. Bilder um 1717 hatte August der Starke, wohl inspiriert durch dementsprechende Eindrü- Gallerie ist […] die schönste in der Welt.«2 cke auf Reisen, eine Funktionsskizze4 für die Aufteilung der Sammlung entworfen, In der zweiten Hälfte des 18. Jahrhunderts war die Dresdner Gemäldegalerie nach der das Sammlungsgut und nicht die historische Klassifizierung das Ordnungs- bereits ein Anziehungspunkt für Künstler, Intellektuelle und kulturaffine Reisende kriterium darstellte. -

O Mito De Apolo E Dafne

o mito de apolo e dafne Sobre o autor LouiS de SiLveStre (1675-1760) Louis de Silvestre nasceu em Sceaux, cidade ao sul de Paris, França, no dia 23 de junho de 1675. Filho de Israel Silvestre, pintor e gravador oficial do Delfim Luís da França. Teve suas primeiras lições de pintura com o pai, sendo depois treinado por Charles Le Brun e Bon Boullogne. Parte para Roma, a fim de terminar seus estudos, onde é acolhido por Carlo Maratta, que terá imensa influência em sua pintura. Especializa-se na pintura histórica e de retratos. Retorna a Paris em 1702, sendo aceito na Academia Real de Pintura e Escultura logo em seguida. Torna-se professor dessa instituição em 1706. Destacam-se desse período a cena bíblica do paralítico do templo e o retrato do rei francês Luís XV, de 1715, mantido na Galeria de Dresden (Duissieux, 1876). Recebe convite do príncipe Frederico Augusto da Saxônia para trabalhar em Dresden, na corte de seu pai, o rei Augusto II da Polônia.1 Silvestre aceita a oferta e recebe dispensa da corte francesa, chegando em Dresden em 1718. Tanto Augusto II, quanto seu filho, admiravam o trabalho de Silvestre sobremaneira, concedendo-lhe as maiores honras disponíveis para o artista. Foi escolhido pintor oficial da corte, depois diretor da Academia de Dresden, em 1727. O príncipe Frederico, agora Augusto III da Polônia, concede-lhe um título nobiliárquico em 1741, fazendo o mesmo com 1 Entre os séculos XVI e XVIII, a Polônia e a Lituânia formavam uma monarquia dual e eletiva, chamada de Comunidade Polaco-Lituana. -

Porcelain Acquisitions Through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net, 2020

1. Introduction Ever since the discovery of the maritime routes to America by Christopher Columbus in 1492, and to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498, the global expansion of trade and trade routes influenced European culture in an unprecedented man- ner. Knowledge about geography and foreign nations expanded, and the intro- duction of new consumables such as tea and chocolate transformed European table culture. Silk and fine cottons from China and India, once brought to the West via the Silk Roads, now arrived in large quantities at the European courts. The European global expansion had its downsides, of course. The conquest of the Americas led to the expulsion, exploitation and eradication of its indigenous peoples. The trade in sugar cane products became the linchpin of colonial rule on the Caribbean islands. After the extinction of almost the entire native pop- ulation, large areas became available for cultivation. Millions of Africans were deported and enslaved over the course of 400 years to work on the plantations under inhuman conditions. One trade item, which also found its way to Europe with the growing maritime traffic, was Chinese porcelain. Still a mysterious substance in the 16th century, vessels made from the luxurious-looking material quickly gained wide popularity with the intensification of the export trade by the Dutch. Millions of East Asian porcelains reached Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, partly through the professional East Asia trading companies and partly through private enterprise. Chinese and – later – Japanese porcelain soon became deeply anchored in European culture, where it was used for its intended purpose as tableware, as gifts exchanged between royal courts, or as decorative and useful items in the households of even the general public. -

Geist Und Glanz Der Dresdner Gemäldegalerie

Dresden_Umschlag_070714 15.07.14 16:23 Seite 1 Geist und Glanz der Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Rund hundert Meisterwerke berühmter Künstler, darunter Carracci, van Dyck, Velázquez, Lorrain, Watteau und Canaletto, veranschau lichen Entstehen und Charakter der legendär reichen Dresdner Gemälde - galerie in Barock und Aufklärung. Im »Augusteischen Zeitalter« der sächsischen Kurfürsten und polnischen Könige August II. (1670–1733) und August III. (1696–1763), einer Zeit der wirtschaft lichen und kultu- Dr Geis rellen Blüte, dienten zahlreiche Bauprojekte und die forcierte Entwick- esdner Gemäldegal lung der königlichen Sammlungen dazu, den neuen Machtanspruch des t und Glanz der Dresdner Hofs zu demonstrieren. Damals erhielt die Stadt mit dem Bau von Hof- und Frauenkirche ihre heute noch weltberühmte Silhouette. Renommierte Maler wie der Franzose Louis de Silvestre (1675–1760) oder der Italiener Bernardo Bellotto (1722–1780) wurden als Hofkünst- ler verpflichtet. Diese lebendige und innovative Zeit bildet den Hinter- grund, vor dem die Meisterwerke ihre Geschichten erzählen. erie HIRMER WWW.HIRMERVERLAG.DE HIRMER Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 1 Rembrandt Tizian Bellotto Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 2 Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:30 Seite 3 Rembrandt Geist und Glanz der Tizian Dresdner Gemäldegalerie Bellotto Herausgegeben von Bernhard Maaz, Ute Christina Koch und Roger Diederen HIRMER Dresden_Inhalt_070714 07.07.14 15:31 Seite 4 Dresden_Inhalt_070714 15.07.14 16:16 Seite 5 Inhalt 6 Grußwort 8 Vorwort Bernhard Maaz -

Stephano Torelli's “Coronation Portrait of Catherine II”: Crowns As a Visual Formula of the Lands of the Russian Empire

UDC 75.04 Вестник СПбГУ. Искусствоведение. 2020. Т. 10. Вып. 2 Stephano Torelli’s “Coronation Portrait of Catherine II”: Crowns as a Visual Formula of the Lands of the Russian Empire* E. A. Skvortcova Saint Petersburg State University, 7–9, Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation For citation: Skvortcova, Ekaterina. “Stephano Torelli’s ‘Coronation Portrait of Catherine II’: Crowns as a Visual Formula of the Lands of the Russian Empire”. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. Arts 10, no. 2 (2020): 274–299. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu15.2020.206 The “Coronation portrait of Catherine II” by Stephano Torelli introduces a new type of ico- nography of the Russian Empress in which she appears as a bearer of multiple (i. e. four) crowns. Whereas originally such a portrait type in European art served as a representation of the several titles of the ruler and correspondent lands joined in a personal union, it became a representation of the titles of Catherine II as the Russian Empress and tsarina of the conquered tsarstva of Kazan, Astrakhan and Siberia. The theme of titles and lands of the Empire had al- ready developed in 18th-century Russia in other forms (allegorical figures, coats-of-arms) and visual media (decorative painting and sculpture). Circa 10 examples collected here for the first time are set side by side with their European counterparts. Three types of representations of native and conquered territories emerged in which the very choice of particular titles and the place of their symbolic representation in composition accentuated different aspects in the con- cept of the Russian Empire. -

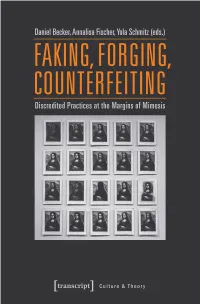

Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting

Daniel Becker, Annalisa Fischer, Yola Schmitz (eds.) Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting Daniel Becker, Annalisa Fischer, Yola Schmitz (eds.) in collaboration with Simone Niehoff and Florencia Sannders Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting Discredited Practices at the Margins of Mimesis Funded by the Elite Network of Bavaria as part of the International Doctoral Program MIMESIS. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3762-9. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contac- ting [email protected] © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Cover concept: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld -

Miniatury Europejskie Collection of European Miniatures

The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Muzeum Zamek Królewski w Warszawie Katalog zbiorów Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum Collection of European Miniatures Miniatury europejskie Catalogue The Royal Castle in Warsaw Katalog zbiorów – Museum European Miniatures Miniatury europejskie Hanna Małachowicz Catalogue Collection of Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum Miniatury europejskie Katalog zbiorów The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum Collection of European Miniatures Catalogue The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum Collection of European Miniatures Catalogue Hanna Małachowicz The Royal Castle in Warsaw – Museum Warsaw 2018 Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum Miniatury europejskie Katalog zbiorów Hanna Małachowicz Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum Warszawa 2018 Redakcja i korekta tekstów polskich: Editing and proofreading of Polish version: Daniela Galas Tłumaczenie: Translation: Anne-Marie Fabianowska Korekta tekstów angielskich: Proofreading of English version: Maria Aldridge Indeks: Index: Grażyna Waluga Opracowanie graficzne, skład i łamanie: Graphic design, pre-press, typesetting: Zofia Tomaszewska Autorzy fotografii: Photographs: Andrzej Ring, Lech Sandzewicz oraz wymienieni w spisie ilustracji porównawczych na s. 259 as well as those indicated in the list of comparative illustrations on p. 260 © Copyright by Zamek Królewski w Warszawie – Muzeum 2018 ISBN 978-83-7022-238-3 Arx Regia® Ośrodek Wydawniczy Zamku Królewskiego w Warszawie – Muzeum plac Zamkowy 4, 00-277 Warszawa tel. 22 35 55 232, 22 35 55 -

Sächsische Kunstkammer in Dresden Geschichte Einer Sammlung Die Kurfürstlich- Sächsische Herzlicher Dank Kunstkammer

Die kurfürstlich- sächsische Kunstkammer in Dresden Geschichte einer Sammlung Die kurfürstlich- sächsische Herzlicher dank Kunstkammer freunde des grünen gewölbes e.v. MUSEIS SAXONICIS USUI – in Dresden freunde der staatlichen Kunstsammlungen dresden e.v. dr. frank Knothe, dresden Geschichte einer tavolozza foundation, münchen thomas färber, genf Sammlung ermöglichten den druck dieses bandes Herausgegeben im au ftrag der staatlicH en Kunstsammlungen dr esden von di r K syndram und marti na mi n n i ng san dstei n ver lag Inhalt 8 Di r K syn dram · marti na mi n n i ng 142 Peter PlaSSmeyer 246 Di rK Weber 380 Clau dia br i n K Literaturbericht zur Dresdner Kunstkammer »liegen hir und da in der grösten confusion herum« »Alles was frembd, das auß den Indias kombt« »auf daß Ich alles zu sehen bekhomme« Die Verwahrung der Dresdner Kunstkammer im Zwinger Von stummen Zeugen und illustrativen Zeugnissen Die Dresdner Kunstkammer bis zu ihrer Auflösung im 19. Jahrhundert exotischer Welten in der Dresdner Kunstkammer und ihr Publikum im 17. Jahrhundert 14 Di r K syn dram Die Anfänge der Dresdner Kunstkammer 152 Marti na mi n n i ng 262 Klaus ThalH eim 408 Peter Wiegand Die Auflösung der königlich-sächsischen Kunstkammer Minerale, Gesteine und Fossilien Die Kunstkammer in der Quellenüberlieferung 46 MattH ias dämmig im Jahr 1832 in der Dresdner Kunstkammer des Hauptstaatsarchivs Dresden Gabriel Kaltemarckts Bedencken, wie Mit einem Exkurs zu den Kunstkammerstücken eine kunst-cammer aufzu richten seyn mochte im Archivbestand von 1587 mit einer Einleitung -

SKD-Jahresbericht-2009.Pdf

für Dresden des18.JahrhundertsMalerei Wirklichkeit.« und Sehnsucht »Wunschbilder. BlickindieAusstellung Titel: –1709) (1548 derKunst« im Spiegel Ehen undAllianzen Sachsen undDänemark– »Mit Fortuna übersMeer. Die Sonderausstellung Staatlich E Ku nStsammlu ngEn Dresden · JAh resbEricht 2009 2009 Jahresbericht 2009 Kunsthalle im Lipsiusbau Zwinger Schloss Pillnitz, Bergpalais Seite 4 i nstitution mit freundlicher Vorwort im Wan del u nterstützung Seite 27 Seite 35 Von barock Die Staatlichen Kunstsammlungen Gemeinsam »Für Canaletto« – bis baselitz Dresden als Staatsbetrieb im Ein Dresdner Wahrzeichen braucht Freistaat Sachsen Unterstützung! Seite 7 Seite 28 Seite 36 Wirtschaftsdaten Freundeskreise son der- Seite 30 Seite 39 ausstellungen Kunstsammlungen und Ethno Sponsoren und Förderer 2009 graphische Sammlungen unter zeichnen Kooperationsvertrag Seite 13 aus den sammlu ngen Sonderausstellungen Seite 31 in Dresden, Sachsen Zwei Direktoren verabschieden und Deutschland 2009 sich – Wechsel bei Alten Meistern Seite 43 und KupferstichKabinett Erwerbungen und Schenkungen Seite 24 Sonderausstellungen im Seite 50 Ausland 2009 Publikationen Seite 52 Recherchen und Restitutionen Seite 53 Restaurierungen Japanisches Palais Albertinum Residenzschloss Wissenschaft Seite 62 museumsbauten u n d Forsch u ng Zum Beispiel: Kooperation mit der Technischen Universität Dresden Seite 77 Seite 59 Seite 63 Unsichtbare und Wissenschaftliche Projekte Zum Beispiel: Staatliche Ethno sichtbare Architektur und Kooperationen graphische Sammlungen Sachsen Seite 59 -

November 2014 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 31, No. 2 November 2014 Jacob Jordaens, Merry Company, c. 1644. Watercolor over black chalk, heightened with white gouache, 21.9 x 23.8 cm. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Exhibited at The Getty Center, Los Angeles, October 14, 2014 – January 11, 2015. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President – Amy Golahny (2013-2017) Lycoming College Williamsport PA 17701 Vice-President – Paul Crenshaw (2013-2017) Providence College Department of Art History 1 Cummingham Square Providence RI 02918-0001 Treasurer – Dawn Odell Lewis and Clark College 0615 SW Palatine Hill Road Portland OR 97219-7899 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 HNA News ............................................................................1 Lloyd DeWitt (2012-2016) Stephanie Dickey (2013-2017) Personalia ............................................................................... 4 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Boston Conference Photos ....................................................5 Walter Melion (2014-2018) Exhibitions ......................................................................... -

The Aeneas Gallery

The Aeneas Gallery ... Ever since Primaticcio’s creation of the Gallery of François I at the Chateau of Fontainebleau, in France painted galleries have become an ostentatious political or social statement for those who commission them. There was a wealth of examples in the seventeenth century, many of which have now disappeared. These include the Gallery of the Life of Marie de Medici painted by Rubens (1622-25), the Hall of Mirrors by Charles Le Brun at Versailles (1679-84) and private galleries such as the one in the Hotel Lambert (c.1650-58). In the early eighteenth century examples include the Mississippi Gallery of the Royal Bank (1720) by the Italian painter The Gallery Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675-1741) and the gallery by Charles de La Fosse (1636- of 1716) for financier and collector Pierre Crozat (1705-07). As the century progressed, the fashion waned. Highlights of this historical episode include the Aeneas gallery at the Palais-Royal Columns in Paris, home to the three large canvases by Coypel and distinguished by its artistic value that was acknowledged by its contemporaries : indeed the duke of Orleans soon had an ... engraving made of it. European Art After the death in 1701 of the brother of Louis XIV, his son Philippe, duke of Orleans who from the Fourteenth would become regent when the king died in 1715, asked his chief painter, Antoine Coypel to Eighteenth Century (1661-1722), who was already a celebrity, to decorate a large gallery that he had had built by Jules Hardouin-Mansart in 1698-1700 at the Palais-Royal overlooking the rue de Richelieu.