November 2014 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

Annual Report and Accounts 2019

IMPERIAL BRANDS PLC BRANDS IMPERIAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 ACCOUNTS AND REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2019 OUR PURPOSE WE CAN I OWN Our purpose is to create something Everything See it, seize it, is possible, make it happen better for the world’s smokers with together we win our portfolio of high quality next generation and tobacco products. In doing so we are transforming WE SURPRISE I AM our business and strengthening New thinking, My contribution new actions, counts, think free, our sustainability and value creation. exceed what’s speak free, act possible with integrity OUR VALUES Our values express who we are and WE ENJOY I ENGAGE capture the behaviours we expect Thrive on Listen, challenge, share, make from everyone who works for us. make it fun connections The following table constitutes our Non-Financial Information Statement in compliance with Sections 414CA and 414CB of the Companies Act 2006. The information listed is incorporated by cross-reference. Additional Non-Financial Information is also available on our website www.imperialbrands.com. Policies and standards which Information necessary to understand our business Page Reporting requirement govern our approach1 and its impact, policy due diligence and outcomes reference Environmental matters • Occupational health, safety and Environmental targets 21 environmental policy and framework • Sustainable tobacco programme International management systems 21 Climate and energy 21 Reducing waste 19 Sustainable tobacco supply 20 Supporting wood sustainability -

Black Tronies in Seventeenth-Century Flemish Art and the African Presence

tronies BlackBernadette van Haute* in seventeenth-century Flemish art and the African presence * Bernadette van Haute is Associate the Maghreb cannot have been very numerous Professor in the Department of Art History, in Antwerp at that time, and it may be that Visual Arts and Musicology at the University all three masters [Rubens, Van Dyck and of South Africa. Jordaens] used the same model’. More recently Kolfin (2008:78) made a similar statement: Abstract Having a genuine black model at one’s disposal must have been a great event In this article I examine the production of artistically speaking. ... at least two other tronies or head studies of people of African painters from Rubens’ circle made oil origin made by the Flemish artists Peter Paul sketches of this man which seem to have Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, Jan I Brueghel, been inspired by Rubens’ study heads: Jacob Jordaens and Gaspar de Crayer in an Jacob Jordaens ... around 1620 and attempt to uncover their use of Africans1 as Gaspar de Crayer ... in the mid-1620s. models. In order to contextualise the research, Although Jordaens’ studies are definitely of the actual presence of Africans in Flanders the same man, this is harder to ascertain in the case of De Crayer’s work. is investigated. Although no documentation exists to calculate even an approximate Adding to this point of view, Massing (2011:1) number of Africans living in Flanders at that states that Rubens painted the same person time, travel accounts of foreigners visiting four times in the Brussels painting, ‘suggesting the commercial city of Antwerp testify that people of African origin were still rare in to its cosmopolitan character. -

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

Sara Fox [email protected] Tel +1 212 636 2680

For Immediate Release May 18, 2012 Contact: Sara Fox [email protected] tel +1 212 636 2680 A MASTERPIECE BY ROMANINO, A REDISCOVERED RUBENS, AND A PAIR OF HUBERT ROBERT PAINTINGS LEAD CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE, JUNE 6 Sale Includes Several Stunning Works From Museum Collections, Sold To Benefit Acquisitions Funds GIROLAMO ROMANINO (Brescia 1484/87-1560) Christ Carrying the Cross Estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000 New York — Christie’s is pleased to announce its summer sale in New York of Old Master Paintings on June 6, 2012, at 5 pm, which primarily consists of works from private collections and institutions that are fresh to the market. The star lot is the 16th-century masterpiece of the Italian High Renaissance, Christ Carrying the Cross (estimate: $2,500,000-3,500,000) by Girolamo Romanino; see separate press release. With nearly 100 works by great French, Italian, Flemish, Dutch and British masters of the 15th through the 19th centuries, the sale includes works by Sir Peter Paul Rubens, Hubert Robert, Jan Breughel I, and his brother Pieter Brueghel II, among others. The auction is expected to achieve in excess of $10 million. 1 The sale is highlighted by several important paintings long hidden away in private collections, such as an oil-on-panel sketch for The Adoration of the Magi (pictured right; estimate: $500,000 - $1,000,000), by Sir Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen, Westphalia 1577- 1640 Antwerp). This unpublished panel comes fresh to market from a private Virginia collection, where it had been in one family for three generations. -

Juul Compatible

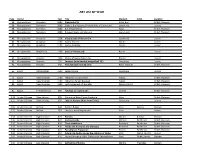

E-TRON JUUL E-Tron E-Cigarette 500 Puff Full Flavor 16mg ETF JUUL Starter Kit JSK E-Tron E-Cigarette 500 Puff Light 16mg ETL JUUL Basic Kit JBK E-Tron E-Cigarette 500 Puff Menthol 16mg ETM JUUL USB Charger 1pk JUSB JAK JUUL Charging Cable 2.6ft JUSB1 JAK E-Cigarette Box Regular 16mg 20ea 8130 JUUL Duet Dual Charger JUSB2 JAK E-Cigarette Box Menthol 16mg 20ea 8131 JUUL The Gem Magnetic USB Charger JUSB3 JAK E-Cigarette Box Regular 36mg 20ea 8132 JAK E-Cigarette Box Menthol 36mg 20ea 8133 JUUL Flavor Pods Classic Tobacco 4pk JPT JAK E-Cigarette Box Variety (Blue) 16mg 20ea 8134 JUUL Flavor Pods Classic Menthol 4pk JPL JAK E-Cigarette Box Variety (White) 16mg 20ea 8135 JUUL Flavor Pods Virginia Tobacco 4pk JPV JAK E-Cigarette Box Variety 36mg 20ea 8137 JUUL Flavor Pods Cool Mint 4pk JPC JAK E-Hookah Box Variety 16mg 20ea 8136 AIRBENDER (JUUL COMPATIBLE) JAK E-Cigarette 3-Tier Display 16mg 60ea 8140 Airbender Flavor Pods Gypsy Tantrum 4pk APG JAK E-Cigarette 4-Tier Display 16mg 80ea 8141 Airbender Flavor Pods High Wire 4pk APH Airbender Flavor Pods Paladin 4pk APP JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Regular 16mg 8100 Airbender Flavor Pods Pinkie 4pk APK JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Menthol 16mg 8101 Airbender Flavor Pods Pitaya On Ice 4pk API JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Regular 36mg 8102 Airbender Flavor Pods Harassmint 4pk APM JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Menthol 36mg 8103 Airbender Flavor Pods New Shorts 4pk APN JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Apple 16mg 8104 Airbender Flavor Pods Strawberry 4pk APS JAK E-Cigarette 800 Puff Cherry 16mg 8105 Airbender Flavor Pods Cucumber -

Art List by Year

ART LIST BY YEAR Page Period Year Title Medium Artist Location 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Standard of Ur Inlaid Box British Museum 36 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Stele of the Vultures (Victory Stele of Eannatum) Limestone Louvre 38 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Bull Headed Harp Harp British Museum 39 Mesopotamia Sumerian 2600 Banquet Scene cylinder seal Lapis Lazoli British Museum 40 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2254 Victory Stele of Narum-Sin Sandstone Louvre 42 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Seated Diorite Louvre 43 Mesopotamia Akkadian 2100 Gudea Standing Calcite Louvre 44 Mesopotamia Babylonian 1780 Stele of Hammurabi Basalt Louvre 45 Mesopotamia Assyrian 1350 Statue of Queen Napir-Asu Bronze Louvre 46 Mesopotamia Assyrian 750 Lamassu (man headed winged bull 13') Limestone Louvre 48 Mesopotamia Assyrian 640 Ashurbanipal hunting lions Relief Gypsum British Museum 65 Egypt Old Kingdom 2500 Seated Scribe Limestone Louvre 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun hunting fowl Fresco British Museum 75 Egypt New Kingdom 1400 Nebamun funery banquet Fresco British Museum 80 Egypt New Kingdom 1300 Last Judgement of Hunefer Papyrus Scroll British Museum 81 Egypt First Millenium 680 Taharqo as a sphinx (2') Granite British Museum 110 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Corinthian Black Figure Amphora Vase British Museum 111 Ancient Greece Orientalizing 625 Lady of Auxerre (Kore from Crete) Limestone Louvre 121 Ancient Greece Archaic 540 Achilles & Ajax Vase Execias Vatican 122 Ancient Greece Archaic 510 Herakles wrestling Antaios Vase Louvre 133 Ancient Greece High -

Fillegorical Truth-Telling Via the Ferninine Baroque: Rubensg Material Reality

Fillegorical Truth-telling via the Ferninine Baroque: RubensgMaterial Reality bY Maria Lydia Brendel fi Thesls submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial folfiilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of flrt History McGIll Uniuerslty Montréal, Canada 1999 O Marfa lgdlo Brendel, 1999 National Library Bibliothèque nationale of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K 1A ON4 Ottawa ON K1A ON4 Canada Canada Your hls Votre roferenw Our fib Notre réMrencs The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothêque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sel1 reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in rnicrofonn, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/film, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantiaî extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. Table of Contents Bcknowledgements .............................................................................................................. -

Hans Memling's Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ And

Volume 5, Issue 1 (Winter 2013) Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ and the Discourse of Revelation Sally Whitman Coleman Recommended Citation: Sally Whitman Coleman, “Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ and the Discourse of Revelation,” JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013), DOI: 10.5092/jhna.2013.5.1.1 Available at https://jhna.org/articles/hans-memlings-scenes-from-the-advent-and-triumph-of- christ-discourse-of-revelation/ Published by Historians of Netherlandish Art: https://hnanews.org/ Republication Guidelines: https://jhna.org/republication-guidelines/ Notes: This PDF is provided for reference purposes only and may not contain all the functionality or features of the original, online publication. This is a revised PDF that may contain different page numbers from the previous version. Use electronic searching to locate passages. This PDF provides paragraph numbers as well as page numbers for citation purposes. ISSN: 1949-9833 JHNA 5:1 (Winter 2013) 1 HANS MEMLING’S SCENES FROM THE ADVENT AND TRIUMPH OF CHRIST AND THE DISCOURSE OF REVELATION Sally Whitman Coleman Hans Memling’s Scenes from the Advent and Triumph of Christ (ca. 1480, Alte Pinakothek, Munich) has one of the most complex narrative structures found in painting from the fifteenth century. It is also one of the earliest panoramic landscape paintings in existence. This Simultanbild has perplexed art historians for many years. The key to understanding Memling’s narrative structure is a consideration of the audience that experienced the painting four different times over the course of a year while participating in the major Church festivals. -

The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

ART AND BUSINESS IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NAPLES: THE COLLECTING, DEALING AND PATRONAGE PRACTICES OF GASPARE ROOMER by Chantelle Lepine-Cercone A thesis submitted to the Department of Art History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (November, 2014) Copyright ©Chantelle Lepine-Cercone, 2014 Abstract This thesis examines the cultural influence of the seventeenth-century Flemish merchant Gaspare Roomer, who lived in Naples from 1616 until 1674. Specifically, it explores his art dealing, collecting and patronage activities, which exerted a notable influence on Neapolitan society. Using bank documents, letters, artist biographies and guidebooks, Roomer’s practices as an art dealer are studied and his importance as a major figure in the artistic exchange between Northern and Sourthern Europe is elucidated. His collection is primarily reconstructed using inventories, wills and artist biographies. Through this examination, Roomer emerges as one of Naples’ most prominent collectors of landscapes, still lifes and battle scenes, in addition to being a sophisticated collector of history paintings. The merchant’s relationship to the Spanish viceregal government of Naples is also discussed, as are his contributions to charity. Giving paintings to notable individuals and large donations to religious institutions were another way in which Roomer exacted influence. This study of Roomer’s cultural importance is comprehensive, exploring both Northern and Southern European sources. Through extensive use of primary source material, the full extent of Roomer’s art dealing, collecting and patronage practices are thoroughly examined. ii Acknowledgements I am deeply thankful to my thesis supervisor, Dr. Sebastian Schütze. -

The Spell of Belgium

The Spell of Belgium By Isabel Anderson THE SPELL OF BELGIUM CHAPTER I THE NEW POST THE winter which I spent in Belgium proved a unique niche in my experience, for it showed me the daily life and characteristics of a people of an old civilization as I could never have known them from casual meetings in the course of ordinary travel. My husband first heard of his nomination as Minister to Belgium over the telephone. We were at Beverly, which was the summer capital that year, when he was told that his name was on the list sent from Washington. Although he had been talked of for the position, still in a way his appointment came as a surprise, and a very pleasant one, too, for we had been assured that “Little Paris” was an attractive post, and that Belgium was especially interesting to diplomats on account of its being the cockpit of Europe. After receiving this first notification, L. called at the “Summer White House” in Beverly, and later went to Washington for instructions. It was not long before we were on our way to the new post. Through a cousin of my husband’s who had married a Belgian, the Comte de Buisseret, we were able to secure a very nice house in Brussels, the Palais d’Assche. As it was being done over by the owners, I remained in Paris during the autumn, waiting until the work should be finished. My husband, of course, went directly to Brussels, and through his letters I was able to gain some idea of what our life there was to be. -

Cultura, Vol. 21 | 2005 Poder De Convencimento E Narração Imagética Na Pintura Portuguesa Da Contra-R

Cultura Revista de História e Teoria das Ideias vol. 21 | 2005 Livro e Iconografia Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão Edição electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 DOI: 10.4000/cultura.2951 ISSN: 2183-2021 Editora Centro de História da Cultura Edição impressa Data de publição: 1 Janeiro 2005 Paginação: 65-76 ISSN: 0870-4546 Refêrencia eletrónica Vítor Serrão, « Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra- reforma », Cultura [Online], vol. 21 | 2005, posto online no dia 26 maio 2016, consultado a 21 abril 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/cultura/2951 ; DOI : 10.4000/cultura.2951 Este documento foi criado de forma automática no dia 21 Abril 2019. © CHAM — Centro de Humanidades / Centre for the Humanities Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-r... 1 Poder de convencimento e narração imagética na pintura portuguesa da contra-reforma A influência de um gravado segundo Seghers numa tela do Convento dos Paulistas de Portel The power of persuasion and images narrative in counter-reformation Portuguese painting: the influente of an engraving following Seghers in a canvas of the Paulistas Monastery at Portel Vítor Serrão 1. A História da Arte reconhece hoje o papel muito destacado que foi assumido pela imagem gravada nos sucessivos processos de evolução artística.