The Collecting, Dealing and Patronage Practices of Gaspare Roomer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Rough Guide to Naples & the Amalfi Coast

HEK=> =K?:;I J>;HEK=>=K?:;je CVeaZh i]Z6bVaÒ8dVhi D7FB;IJ>;7C7B<?9E7IJ 7ZcZkZcid BdcYgV\dcZ 8{ejV HVc<^dg\^d 8VhZgiV HVciÉ6\ViV YZaHVcc^d YZ^<di^ HVciVBVg^V 8{ejVKiZgZ 8VhiZaKdaijgcd 8VhVaY^ Eg^cX^eZ 6g^Zcod / AV\dY^EVig^V BVg^\a^Vcd 6kZaa^cd 9WfeZ_Y^_de CdaV 8jbV CVeaZh AV\dY^;jhVgd Edoojda^ BiKZhjk^jh BZgXVidHVcHZkZg^cd EgX^YV :gXdaVcd Fecf[__ >hX]^V EdbeZ^ >hX]^V IdggZ6ccjco^ViV 8VhiZaaVbbVgZY^HiVW^V 7Vnd[CVeaZh GVkZaad HdggZcid Edh^iVcd HVaZgcd 6bVa[^ 8{eg^ <ja[d[HVaZgcd 6cVX{eg^ 8{eg^ CVeaZh I]Z8Vbe^;aZ\gZ^ Hdji]d[CVeaZh I]Z6bVa[^8dVhi I]Z^haVcYh LN Cdgi]d[CVeaZh FW[ijkc About this book Rough Guides are designed to be good to read and easy to use. The book is divided into the following sections, and you should be able to find whatever you need in one of them. The introductory colour section is designed to give you a feel for Naples and the Amalfi Coast, suggesting when to go and what not to miss, and includes a full list of contents. Then comes basics, for pre-departure information and other practicalities. The guide chapters cover the region in depth, each starting with a highlights panel, introduction and a map to help you plan your route. Contexts fills you in on history, books and film while individual colour sections introduce Neapolitan cuisine and performance. Language gives you an extensive menu reader and enough Italian to get by. 9 781843 537144 ISBN 978-1-84353-714-4 The book concludes with all the small print, including details of how to send in updates and corrections, and a comprehensive index. -

Mattia & Marianovella Romano

Mattia & MariaNovella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings A Selection of Master Drawings Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Drawings are sold mounted but not framed. Master Drawings © Copyright Mattia & Maria Novelaa Romano, 2015 Designed by Mattia & Maria Novella Romano and Saverio Fontini 2015 Mattia & Maria Novella Romano 36, Borgo Ognissanti 50123 Florence – Italy Telephone +39 055 239 60 06 Email: [email protected] www.antiksimoneromanoefigli.com Mattia & Maria Novella Romano A Selection of Master Drawings 2015 F R FRATELLI ROMANO 36, Borgo Ognissanti Florence - Italy Acknowledgements Index of Artists We would like to thank Luisa Berretti, Carlo Falciani, Catherine Gouguel, Martin Hirschoeck, Ellida Minelli, Cristiana Romalli, Annalisa Scarpa and Julien Stock for their help in the preparation of this catalogue. Index of Artists 15 1 3 BARGHEER EDUARD BERTANI GIOVAN BAttISTA BRIZIO FRANCESCO (?) 5 9 7 8 CANTARINI SIMONE CONCA SEBASTIANO DE FERRARI GREGORIO DE MAttEIS PAOLO 12 10 14 6 FISCHEttI FEDELE FONTEBASSO FRANCESCO GEMITO VINCENZO GIORDANO LUCA 2 11 13 4 MARCHEttI MARCO MENESCARDI GIUSTINO SABATELLI LUIGI TASSI AGOSTINO 1. GIOVAN BAttISTA BERTANI Mantua c. 1516 – 1576 Bacchus and Erigone Pen, ink and watercoloured ink on watermarked laid paper squared in chalk 208 x 163 mm. (8 ¼ x 6 ⅜ in.) PROVENANCE Private collection. Giovan Battista Bertani was the successor to Giulio At the centre of the composition a man with long hair Romano in the prestigious work site of the Ducal Palace seems to be holding a woman close to him. She is seen in Mantua.1 His name is first mentioned in documents of from behind, with vines clinging to her; to the sides of 1531 as ‘pictor’, under the direction of the master, during the central group, there are two pairs of little erotes who the construction works of the “Palazzina della Paleologa”, play among themselves, passing bunches of grapes to each which no longer exists, in the Ducal Palace.2 According other. -

GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque Anni Di Attività

GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque anni di attività La GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO, fondata a Torino nel 1993 La Galleria Giamblanco di Torino festeggia da Deborah Lentini e Salvatore Giamblanco, da oltre venticinque anni offre ai suoi clienti dipinti di grandi maestri italiani e stranieri con questo catalogo i suoi primi venticinque anni dal Cinquecento al primo Novecento, attentamente selezionati per qualità e rilevanza storico-artistica, avvalendosi di attività, proponendo al pubblico un’ampia selezione della consulenza dei migliori studiosi. di dipinti dal XV al XIX secolo. Tra le opere più importanti si segnalano inediti di Nicolas Régnier, Mattia Preti, Joost van de Hamme, Venticinque anni di attività Gioacchino Assereto, Cesare e Francesco Fracanzano, Giacinto Brandi, Antonio Zanchi e di molti altri artisti di rilievo internazionale. Come di consueto è presentata anche una ricca selezione di autori piemontesi del Sette e dell’Ottocento, da Vittorio Amedeo Cignaroli a Enrico Gamba, tra cui i due bozzetti realizzati da Claudio Francesco Beaumont per l’arazzeria di corte sabauda, che vanno a completare la serie oggi conservata al Museo Civico di Palazzo Madama di Torino. Catalogo edito per la Galleria Giamblanco da 2017-2018 In copertina UMBERTO ALLEMANDI e 26,00 Daniel Seiter (Vienna, 1647 - Torino, 1705), «Diana e Orione», 1685 circa. GALLERIA GIAMBLANCO DIPINTI ANTICHI Venticinque anni di attività A CURA DI DEBORAH LENTINI E SALVATORE GIAMBLANCO CON LA COLLABORAZIONE DI Alberto Cottino Serena D’Italia Luca Fiorentino Simone Mattiello Anna Orlando Gianni Papi Francesco Petrucci Guendalina Serafinelli Nicola Spinosa Andrea Tomezzoli Denis Ton Catalogo edito per la Galleria Giamblanco da UMBERTO ALLEMANDI Galleria Giamblanco via Giovanni Giolitti 39, Torino tel. -

Il 'Poggio Delle Mortelle'

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “FEDERICO II” FACOLTÀ DI ARCHITETTURA DOTTORATO DI RICERCA IN STORIA DELL’ARCHITETTURA E DELLA CITTÀ XVII CICLO IL ‘POGGIO DELLE MORTELLE’ NELLA STORIA DELL’ARCHITETTURA NAPOLETANA COORDINATORE: PROF. ARCH. FRANCESCO SAVERIO STARACE TUTORE: PROF. ARCH. MARIA RAFFAELA PESSOLANO CANDIDATO: EMILIO RICCIARDI ANNO 2005 Introduzione Il “poggio delle Mortelle” è una piccola area a sud-ovest della collina di San Martino, tra Chiaia e Montecalvario, aperta sul mare in direzione di Posillipo e celebrata dai cronisti per la bellezza del sito e la salubrità dell’aria; prese questo nome, scriveva nella sua guida il canonico Carlo Celano, “perché da cento settant’anni fa vi erano boschi di mirti che noi chiamiamo mortelle, e le frondi di questi servivano per accomodare i cuoi”1. La spiegazione di Celano fu ripresa da tutti gli scrittori di cose napoletane, con la sola eccezione di Ludovico de la Ville sur-Yllon, che agli inizi del XX secolo, basandosi su un documento di compravendita ritrovato nel Grande Archivio di Napoli, formulò l’ipotesi che il toponimo derivasse dalla famiglia “de Trojanis y Mortela”, che abitava in questi luoghi agli inizi del Seicento2. Quale che ne fosse l’origine, la denominazione “delle Mortelle” si affermò con favore crescente a partire dalla metà del XVII secolo, cancellando la memoria dei nomi più antichi (“il Lucchesino”, “lo Ficaro”, “la Caiola”) che distinguevano i diversi fondi rustici e sostituendo indicazioni più generiche (“sopra Chiaia”, “sopra Toledo”, “sotto Sant’Elmo” oppure, dopo la fondazione della chiesa, “sotto Santa Maria Apparente”). I documenti cinque e secenteschi concordano nel chiamare “piazza delle 1 C. -

20-A Richard Diebenkorn, Cityscape I, 1963

RICHARD DIEBENKORN [1922–1993] 20a Cityscape I, 1963 Although often derided by those who embraced the native ten- no human figure in this painting. But like it, Cityscape I compels dency toward realism, abstract painting was avidly pursued by us to think about man’s effect on the natural world. Diebenkorn artists after World War II. In the hands of talented painters such leaves us with an impression of a landscape that has been as Jackson Pollack, Robert Motherwell, and Richard Diebenkorn, civilized — but only in part. abstract art displayed a robust energy and creative dynamism Cityscape I’s large canvas has a composition organized by geo- that was equal to America’s emergence as the new major metric planes of colored rectangles and stripes. Colorful, boxy player on the international stage. Unlike the art produced under houses run along a strip of road that divides the two sides of the fascist or communist regimes, which tended to be ideological painting: a man-made environment to the left, and open, pre- and narrowly didactic, abstract art focused on art itself and the sumably undeveloped, land to the right. This road, which travels pleasure of its creation. Richard Diebenkorn was a painter who almost from the bottom of the picture to the top, should allow moved from abstraction to figurative painting and then back the viewer to scan the painting quickly, but Diebenkorn has used again. If his work has any theme it is the light and atmosphere some artistic devices to make the journey a reflective one. of the West Coast. -

Un Cristo Nudo Del 1400 Rivede La Luce a Lauro Scoperto Un Raro Ciclo Di

Un Cristo nudo del 1400 rivede la luce a Lauro Scoperto un raro ciclo di affreschi del XV secolo a Lauro di Nola. Una rarità iconografica che sta meravigliando gli stessi studiosi. Il 2000, anno giubilare, è trascorso in Campania denso di manifestazioni religiose e appuntamenti culturali che hanno riavvicinato il grande pubblico non solo agli aspetti intimi della fede, ma anche alle necessarie “esteriorità”, tra queste la più ghiotta è stata senza dubbio la mostra artistica sul tema della Croce tenutasi presso la sala Carlo V nel Maschio Angioino. La mostra ricca di straordinari reperti, alcuni dei quali, preziosissimi, mai esposti prima, ha fatto seguito ad un dotto convegno sull’argomento organizzato nei mesi precedenti dal professor Boris Iulianich, emerito nell’Università di Napoli e massimo esperto di storia del Cristianesimo, che ha visto la partecipazione di ben 54 relatori provenienti da ogni angolo del globo. Per rimanere nel tema cristologico vogliamo segnalare una sensazionale scoperta avvenuta nella chiesa di Santa Maria della Pietà a Lauro di Nola (fig. 1), ove nell’ambito di un ciclo di affreschi quattrocenteschi, a lungo rimasti sepolti tra le fondamenta di una chiesa più moderna, spicca una scena del Battesimo di Cristo con un’iconografia assolutamente rara: una ostentatio genitalium in piena regola, che lascia esterrefatti, perché la raffigurazione di nostro Signore completamente nudo, in età adulta è poco meno che eccezionale. In Italia possiamo citare soltanto due altri esempi: il Crocifisso ligneo scolpito da Michelangelo nel convento di Santo Spirito in Firenze ed un mosaico nella cupola del Battistero della Cattedrale di Ravenna risalente al V secolo. -

La Basilica Di San Domenico Maggiore in “Ricerche Sull'arte A

Ricerche sull’arte a Napoli in età moderna saggi e documenti 2015 FONDAZIONE GIUSEPPE E MARGARET DE VITO PER LA STORIA DELL’ARTE MODERNA A NAPOLI Ricerche sull’arte a Napoli in età moderna saggi e documenti 2015 Sommario Presentazione 82 Sabrina Iorio 7 Giancarlo Lo Schiavo Sull’arte marmorea di primo Seicento a Napoli: Iacopo Lazzari, Tommaso Montani, Per Giuseppe De Vito. Un ricordo Francesco Cassano, Giovan Marco Vitale 8 Renato Ruotolo e Giovan Domenico Monterosso 10 Riccardo Naldi 106 Luigi Abetti “ … son de madera incorruptible … ”. Bonaventura Presti architetto certosino Due Ladroni in legno di bosso di Gabriel Joly, “aquila” dimenticata del Rinascimento 133 Paola De Simone mediterraneo Dalla serenata Cerere placata a palazzo Perrelli. Nuovi documenti per le arti a 35 Eduardo Nappi Napoli La chiesa e il convento di San Domenico Maggiore di Napoli. Documenti 167 Renato Ruotolo L’architetto Orazio Angelini e il VII 54 Giuseppe Porzio Congresso degli Scienziati Italiani del 1845 Dagli spalti di Castel Sant’Elmo. Notizie su Didier Bar 193 Indice dei nomi a cura di Luigi Abetti 64 Marco Vaccaro Considerazioni sull’attività di Aert Mijtens in Abruzzo e sulla formazione dei fratelli Bedeschini Eduardo Nappi La chiesa e il convento di San Domenico Maggiore di Napoli. Documenti Gli oltre duecento documenti pubblicati di seguito mettono a disposizione degli studiosi una ricchezza di notizie, sia d’archivio che bibliografiche, utili per chiarire l’articolata vicenda costruttiva della cittadella conventuale di San Domenico Maggiore. Tali documenti, suddivisi topograficamente e ordinati crono- logicamente, coprono un arco temporale compreso tra il XVI e il XIX secolo. -

The Meaning and Significance of 'Water' in the Antwerp Cityscapes

The meaning and significance of ‘water’ in the Antwerp cityscapes (c. 1550-1650 AD) Julia Dijkstra1 Scholars have often described the sixteenth century as This essay starts with a short history of the rise of the ‘golden age’ of Antwerp. From the last decades of the cityscapes in the fine arts. It will show the emergence fifteenth century onwards, Antwerp became one of the of maritime landscape as an independent motif in the leading cities in Europe in terms of wealth and cultural sixteenth century. Set against this theoretical framework, activity, comparable to Florence, Rome and Venice. The a selection of Antwerp cityscapes will be discussed. Both rising importance of the Antwerp harbour made the city prints and paintings will be analysed according to view- a major centre of trade. Foreign tradesmen played an es- point, the ratio of water, sky and city elements in the sential role in the rise of Antwerp as metropolis (Van der picture plane, type of ships and other significant mari- Stock, 1993: 16). This period of great prosperity, however, time details. The primary aim is to see if and how the came to a sudden end with the commencement of the po- cityscape of Antwerp changed in the sixteenth and sev- litical and economic turmoil caused by the Eighty Years’ enteenth century, in particular between 1550 and 1650. War (1568 – 1648). In 1585, the Fall of Antwerp even led The case studies represent Antwerp cityscapes from dif- to the so-called ‘blocking’ of the Scheldt, the most im- ferent periods within this time frame, in order to examine portant route from Antwerp to the sea (Groenveld, 2008: whether a certain development can be determined. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

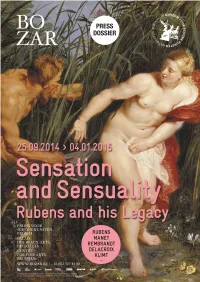

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

NGA | 2017 Annual Report

N A TIO NAL G ALL E R Y O F A R T 2017 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. Board of Trustees COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2017) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Louisa Duemling Mitchell P. Rales Aaron Fleischman Sharon P. Rockefeller Juliet C. Folger David M. Rubenstein Marina Kellen French Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Rose Ellen Greene Chairman Andrew S. Gundlach Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Jane M. Hamilton Richard C. Hedreen Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Kasper Andrew M. Saul Mark J. Kington Kyle J. Krause David W. Laughlin AUDIT COMMITTEE Reid V. MacDonald Andrew M. Saul Chairman Jacqueline B. Mars Frederick W. Beinecke Robert B. Menschel Mitchell P. Rales Constance J. Milstein Sharon P. Rockefeller John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree David M. Rubenstein Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein Tony Podesta William A. Prezant TRUSTEES EMERITI Diana C. Prince Julian Ganz, Jr. Robert M. Rosenthal Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant B. Francis Saul II John Wilmerding Thomas A. Saunders III Fern M. Schad EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Leonard L. Silverstein Frederick W. Beinecke Albert H. Small President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Michelle Smith Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Benjamin F. Stapleton III Franklin Kelly Luther M. -

The Corsini Collection: a Window on Renaissance Florence Exhibition Labels

The Corsini Collection: A Window on Renaissance Florence Exhibition labels © Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, 2017 Reproduction in part or in whole of this document is prohibited without express written permission. The Corsini Family Members of the Corsini family settled in Florence in the middle of the 13th century, attaining leading roles in government, the law, trade and banking. During that time, the Republic of Florence became one of the mercantile and financial centres in the Western world. Along with other leading families, the Corsini name was interwoven with that of the powerful Medici until 1737, when the Medici line came to an end. The Corsini family can also claim illustrious members within the Catholic Church, including their family saint, Andrea Corsini, three cardinals and Pope Clement XII. Filippo Corsini was created Count Palatine in 1371 by the Emperor Charles IV, and in 1348 Tommaso Corsini encouraged the foundation of the Studio Fiorentino, the University of Florence. The family’s history is interwoven with that of the city and its citizens‚ politically, culturally and intellectually. Between 1650 and 1728, the family constructed what is the principal baroque edifice in the city, and their remarkable collection of Renaissance and Baroque art remains on display in Palazzo Corsini today. The Corsini Collection: A Window on Renaissance Florence paints a rare glimpse of family life and loyalties, their devotion to the city, and their place within Florence’s magnificent cultural heritage. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki is delighted that the Corsini family have generously allowed some of their treasures to travel so far from home. -

Encyklopédia Kresťanského Umenia Cár - Pozri Jurodiví/Blázni V Kristu; Rusko

Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia cár - pozri jurodiví/blázni v Kristu; Rusko Georges Becker: Korunovácia cára Alexandra III. a cisárovnej Márie Fjodorovny Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 1 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia N. Nevrev: Roman Veľký prijíma veľvyslanca pápeža Innocenta III (1875) Cár kolokol - Expres: zvon z počiatku 17.st. odliaty na príkaz cára Borisa Godunova (1552-1605); mal 36 ton; bol zavesený v štvormetrovej výške a rozhojdávalo ho 12 ľudí; počas jedného z požiarov spadol a rozbil sa; roku 1654 z jeho ostatkov odlial ruský majster Danilo Danilov ešte väčší zvon; o rok neskoršie zvon praskol úderom srdca; ďalší nasledovník Cára kolokola bol odliaty v Kremli; 24 rokov videl na provizórnej konštrukcii; napokon sa našiel majster, ktorému trvalo deväť mesiacov, kým ho zdvihol na Uspenský chrám; tam zotrval do požiaru roku 1701, keď spadol a rozbil sa; dnešný Cár kolokol bol formovaný v roku 1734, ale odliaty až o rok neskoršie; plnenie formy kovom trvalo hodinu a štvrť a tavba trvala 36 hodín; keď roku 1737 vypukol v Moskve požiar, praskol zvon pri nerovnomernom ochladzovaní studenou vodou; trhliny sa rozšírili po mnohých miestach a jedna časť sa dokonca oddelila; iba tento úlomok váži 11,5 tony; celý zvon váži viac ako 200 ton a má výšku 6m 14cm; priemer v najširšej časti je 6,6m; v jeho materiáli sa okrem klasickej zvonoviny našli aj podiely zlata a striebra; viac ako 100 rokov ostal zvon v jame, v ktorej ho odliali; pred rokom 2000 poverili monumentalistu Zuraba Cereteliho odliatím nového Cára kolokola, ktorý mal odbiť vstup do nového milénia; myšlienka však nebola doteraz zrealizovaná Caracallove kúpele - pozri Rím http://referaty.atlas.sk/vseobecne-humanitne/kultura-a-umenie/48731/caracallove-kupele Heslo CAR – CARI Strana 2 z 39 Marie Žúborová - Němcová: Encyklopédia kresťanského umenia G.