The Spell of Belgium

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crimes of the House of Austria Against Mankind

M llii : III ffillH J—I— "IHiI li II M iHH J> > y 'tc. * - o N «*' ^ * V VV '% «. 3, .<"& %& : C E I U E S OF THE HOUSE OF AUSTRIA AGAINST MANKIND. PROVED BY EXTRACTS FROM THE HISTORIES OF C02E, SCHILLER, ROBERTSON, GRATTAN, AND SISMONDI, "WITH MRS. M. L. PUTNAM^ HISTORY OF THE CONSTITUTION OF HUNGARY, AND ITS RELATIONS WITH AUSTRIA, PUBLISHED IN MAY, 1850. EDITED BY E. Pi "PEABODY. JSWDItDr jBMtiOK- NEW-YORK: G. P. PUTNAM, 10 PARK PLACE 1852. JEM* Entered according to act of Congress, in the year 1852, By rodolphe garrique, In the Cleric's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern District of Ne\v»Yoi'k. PREFACE SECOND EDITION. This work was first published for the benefit of the Hun- garian Fund, on the understanding (which proved a misun- derstanding), of a certain autograph acknowledgment which failed to arrive at the time expected. Those who had the care of the publication consequently took the liberty, without the leave or knowledge of the Edi- tor, who was absent, to mutilate the correspondence that formed the Preface, making it irrelevant within itself, and insignificant altogether. The Preface is therefore wholly left out in this edition, and an Analytic Index is prefixed; and the stereotypes have passed into the hands of the pre- sent publisher, who republishes it, confident that these im- portant passages of unquestionable history will benefit the Hungarian cause, by showing its necessity and justice, al- though it is impossible to benefit the Hungarian Fund by the proceeds of the work. -

9780521819206 Index.Pdf

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-81920-6 - Wilhelm II: The Kaiser’s Personal Monarchy, 1888–1900 John C. G. Röhl Index More information Index Abdul Hamid II, Sultan 125, 222, 768, 938, 939, 68, 70, 103, 124, 130, 331, 338, 361, 363, 944, 946, 947, 948, 950, 951, 952, 953, 483, 484, 485, 536, 551, 636, 646, 988 987 advises Empress Frederick in her relations with Achenbach, Heinrich von (Oberprasident¨ of Wilhelm II 57–8 Province of Brandenburg) 526 Jewish friendships 135 Adolf, Grand Duke of Luxemburg 536, 639, 640, discourtesy towards Wilhelm II 771–2 642 furious reaction to Kruger¨ telegram 791–2 Adolf, Prince of Schaumburg-Lippe (husband of on German antagonism towards Britain 937 Viktoria (Moretta)) 197, 401, 630, 633, relations with Wilhelm II 967 636, 640–2, 643, 648, 801 Vienna incident 77–101 Affie, see Alfred, Duke of Edinburgh effects on Anglo-German relations 487, 488, Africa 489, 490; speech at Frankfurt an der Oder German colonial policy 149–52 73–7 following Bismarck’s dismissal 352–5 ameliorates anti-German attitudes 972 as affected by German-African Company’s accused of discourtesy to Senden-Bibran 973 ownership of the colonies 777–8 involvement in succession question to duchies of South Africa, British colonial policy and its Coburg and Gotha 990 effects on Anglo-German relations 780–98 Albert Victor (Eddy), Duke of Clarence (elder son Ahlwardt, Hermann (anti-Semitic agitator) 465 of Prince of Wales) 103, 124, 126–7, 361, Albedyll, Emil von (Chief of Military Cabinet 482, 483, 653–4 under Kaiser Wilhelm I) 110, 154, -

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011 The Thesis Committee for Laura Kathleen Valeri Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson Richard A. Shiff Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art by Laura Kathleen Valeri, BA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Abstract Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art Laura Kathleen Valeri, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson This thesis examines the impact of Maurice Maeterlinck’s ideas on modern artists. Maeterlinck's poetry, prose, and early plays explore inherently Symbolist issues, but a closer look at his works reveals a departure from the common conception of Symbolism. Most Symbolists adhered to correspondence theory, the idea that the external world within the reach of the senses consisted merely of symbols that reflected a higher, objective reality hidden from humans. Maeterlinck rarely mentioned symbols, instead claiming that quiet contemplation allowed him to gain intuitions of a subjective, truer reality. Maeterlinck’s use of ambiguity and suggestion to evoke personal intuitions appealed not only to nineteenth-century Symbolist artists like Édouard Vuillard, but also to artists in pre-World War I Paris, where a strong Symbolist current continued. Maeterlinck’s ideas also offered a parallel to the theories of Henri Bergson, embraced by the Puteaux Cubists Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. -

Virtus 2017 Binnenwerk.Indb 173 13-02-18 12:38 Virtus 24 | 2017

virtus 24 virtus Adel en heerlijkheden in Québec. De opkomst en het voortleven van een 9 sociale groep en een feodaal instituut (ca. 1600-2000) Benoît Grenier en Wybren Verstegen Handel in heerlijkheden. Aankoop van Hollandse heerlijkheden en motieven 31 van kopers, 1600-1795 virtus Maarten Prins Beschermd en berucht. De manoeuvreerruimte van jonker Ernst Mom binnen 57 2017 het rechtssysteem van zestiende-eeuws Gelre 24 Lidewij Nissen Prussia’s Franconian undertaking. Dynasty, law, and politics in the Holy 75 Roman Empire (1703-1726) 24 2017 Quinten Somsen | Gutsbesitzer zwischen Repräsentation und Wirtschaftsführung. Das Gut 105 Nordkirchen in Westfalen im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert Friederike Scholten Adel op de pastorie. Aristocratische huwelijken van predikanten in de 129 negentiende eeuw Fred Vogelzang 9 789087 047252 9789087047251.pcovr.Virtus2017.indd 2 06-02-18 09:39 pp. 173-186 | Korte bijdragen Yme Kuiper and Huibert Schijf What do Dutch nobles think about themselves? Some notes on a 2016 survey on the identity of the Dutch nobility 173 In the late 1980s, the French sociologist Monique de Saint Martin started her research on no- bility in modern French society with a pilot study among noble families. Many of her noble interlocutors, she noticed, answered her request for an interview with the following puz- zling statement: ‘La noblesse n’existe plus.’ (The [French] nobility does not exist anymore).1 Over the years, the authors of this article have spoken with many people belonging to the Dutch nobility, but they have never heard this statement in their conversations with elder- ly or young nobles. What did strike us, however, was that many of the Dutch nobility do not use their titles in public, and that some hand over business cards both with and without their noble title (or noble title of respect) on it. -

Virtus 2015 Binnenwerk.Indb 246 26-01-16 09:17 Korte Bijdragen

virtus 22 virtus Bergen op Zoom. Residentie en stad 9 Willem van Ham Heren van Holland. Het bezit van Hollandse heerlijkheden onder adel en 37 patriciaat (1500-1795) Maarten Prins virtus De invloed van esthetische ontwikkelingen op de reisbeleving. 63 De waardering van Engelse en Duitse adellijke residenties door Nederlandse 2015 reizigers in de achttiende eeuw 22 Renske Koster Jagen naar macht. Jachtrechten en verschuivende machtsverhoudingen in 81 Twente, 1747-1815 22 2015 Leon Wessels | Een ‘uitgebreide aristocratie’ of een ‘gematigd democratisch beginsel’? Van 103 Hogendorp en de adel als vertegenwoordiger van het platteland (1813-1842) Wybren Verstegen Beleven en herinneren op het slagveld van Waterloo. Een adellijk perspectief 125 (1815-1870) Jolien Gijbels Elites and country house culture in nineteenth-century Limburg 147 Fred Vogelzang De reizende jonkheer. Museumdirecteur Willem Sandberg als cultureel 171 diplomaat Claartje Wesselink 9789087045722.pcovr.Virtus2015.indd 2 19-01-16 20:32 virtus 22 | 2015 Ellis Wasson European nobilities in the twentieth century 246 Yme Kuiper, Nikolaj Bijleveld and Jaap Dronkers, eds, Nobilities in Europe in the twentieth century. Reconversion strategies, memory culture and elite forma- tion, Groningen Studies in Cultural Change, L (Leuven: Peeters, 2015, viii + 357 p., ill., index) This volume incorporates the outcomes of a conference organised by the editors held at the European University Institute (Fiesole, Italy) in 2009 focused on the comparative study of nobilities in the twentieth century. Since the 1950s the British experience dominated the field led by David Spring and F.M.L. Thompson, whose work concentrated on the adaptabil- ity of landed elites in the transformation of an agricultural society into an industrial one. -

Anglo-Habsburg Relations and the Outbreak of the War of Three Kingdoms, 1630-1641

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Charles I and the Spanish Plot: Anglo-Habsburg Relations and the Outbreak of the War of Three Kingdoms, 1630-1641 A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History by Patrick Ignacio O’Neill March 2014 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Thomas Cogswell, Chairperson Dr. Randolph Head Dr. Georg Michels Copyright by Patrick Ignacio O’Neill 2014 The Dissertation of Patrick Ignacio O’Neill is approved: __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Bertolt Brecht posed the question, “Young Alexander conquered India./ He alone?” Like any great human endeavor, this dissertation is not the product of one person’s solitary labors, but owes much to the efforts of a great number of individuals and organizations who have continually made straight my paths through graduate school, through archival research, and through the drafting process. First and foremost, I would like to thank my dissertation chair, Dr. Thomas Cogswell, for his excellent guidance throughout my years at the University of California, Riverside. When I arrived as a first-year graduate student, I had very little certainty of what I wanted to do in the field of Early Modern Britain, and I felt more than a bit overwhelmed at the well-trod historiographical world I had just entered. Dr. Cogswell quickly took me under his wing and steered me gently through a research path that helped me find my current project, and he subsequently took a great interest in following my progress through research and writing. I salute his heroic readings and re-readings of drafts of chapters, conference papers, and proposals, and his perennial willingness to have a good chat over a cup of coffee and to help dispel the many frustrations that come from dissertation writing. -

Keeping up with the Dutch Internal Colonization and Rural Reform in Germany, 1800–1914

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 Keeping Up with the Dutch Internal Colonization and Rural Reform in Germany, 1800–1914 Elizabeth B. Jones HCM 3 (2): 173–194 http://doi.org/10.18352/hcm.482 Abstract Recent research on internal colonization in Imperial Germany empha- sizes how racial and environmental chauvinism drove plans for agri- cultural settlement in the ‘polonized’ German East. Yet policymakers’ dismay over earlier endeavours on the peat bogs of northwest Germany and their admiration for Dutch achievements was a constant refrain. This article traces the heterogeneous Dutch influences on German internal colonization between 1790 and 1914 and the mixed results of Germans efforts to adapt Dutch models of wasteland colonization. Indeed, despite rising German influence in transnational debates over European internal colonization, derogatory comparisons between medi- ocre German ventures and the unrelenting progress of the Dutch per- sisted. Thus, the example of northwest Germany highlights how mount- ing anxieties about ‘backwardness’ continued to mold the enterprise in the modern era and challenges the notion that the profound German influences on the Netherlands had no analog in the other direction. Keywords: agriculture, Germany, internal colonization, improvement, Netherlands Introduction Radical German nationalist Alfred Hugenberg launched his political career in the 1890s as an official with the Royal Prussian Colonization Commission.1 Created by Bismarck in 1886, the Commission’s charge HCM 2015, VOL. 3, no. 2 173 © ELIZABETH B. -

DRAFT 2 Chapter One Stigmatized by Choice: the Self-Fashioning Of

DRAFT 2 Chapter One Stigmatized by Choice: The Self-Fashioning of Anna Katharina Emmerick, 1813 Introduction: Whose Story? The residents of Dülmen had plenty to talk about and worry over in March of 1813. By then, the Westphalian village had seen three regime changes over the course of a decade of war.1 As the front line of the battle between Napoleon’s Imperial France and the other European powers had shifted, passing soldiers made camp in Dülmen’s fields and requisitioned its goods – over 15,000 of them at one point, overwhelming the community’s 2,000 inhabitants. The French Revolution had come to their doorstep: the annexed village’s Augustinian convent was secularized, its peasants emancipated. Twenty of Dülmen’s young men had just recently been conscripted into Napoleon’s Grand Armeé, joining its long march to Russia. Now the Russian campaign was over, all twenty Dülmener soldiers were dead, and not only retreating French but Prussian and Russian troops were heading Dülmen’s way.2 Despite all these pressing concerns, a growing number of Dülmeners were talking in the streets and taverns about something else entirely: Anna Katharina Emmerick, the bedridden spinster forced to leave Dülmen’s convent upon its secularization. This peasant woman, rumor 1 At the time of Emmerick’s birth, Dülmen was part of the Prince-Bishopric of Münster. The last Prince-Bishop of Münster died in exile in Vienna in 1801, and the Prince-Bishopric was formally dissolved by the Reichsdeputationshauptschluß of 25 February 1803 (for more on this document, see p. 14 below). -

The Drawing Ezine

Drawing Workshops Portrait Drawing Painting for Beginners Workshops Workshops THE DRAWING EZINE How to Draw the Portrait in Conte The visual language of drawing has evolved tremen- dously over the past few centuries. An almost magi- cal trick happens within our cerebrum when we view a flat surface on which marks have been inscribed. Look- ing at a portrait drawing – particularly a master draw- ing of exquisite lines and tones – we immediately see past the markings of chalk and engage in a visual and emotional dialogue. The more masterful the drawing the more we engage it. This, too, is also the brutal reality of portrait drawing. If the threshhold of plausibility, namely, does the draw- ing read accurately, is not met then our work is readily dismissed. Additionally the spirit of a drawing, it’s emo- tional pull, is critically important. I am thinking of the portrait drawings of van Gogh when I say this. Con- versely, a technically accurate rendering alone will not make a drawing a ‘success’. The saccherine works Peter Paul Rubens, Isabella Brant, of William-Adolphe Bougeureau (1825-1905) come to A Portrait Drawing, 1621 mind. © 1998-2013. All rights reserved. William-Adolphe Bouguereau, Vincent van Gogh, Drawing of a Woman Self-Portrait In the late 19th Century Bougeureau was considered the greatest painter of his time – his paintings commanded astounding prices and he was a much sought after guest at high society galas while up on the hill in Montmartre artists such as van Gogh and Modigliani huddled over cold cups of coffee for their sustenance. -

Rubens Was Artist, Scholar, Diplomat--And a Lover of Life

RUBENS WAS ARTIST, SCHOLAR, DIPLOMAT--AND A LOVER OF LIFE An exhibit at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts shows that this Flemish genius truly lived in the right place at the right time by Henry Adams Smithsonian, October, 1993 Of all the great European Old Masters, Rubens has always been the most difficult and puzzling for Americans. Thomas Eakins, the famed American portraitist, once wrote that Rubens' paintings should be burned. Somewhat less viciously, Ernest Hemingway made fun of his fleshy nudes—which have given rise to the adjective "Rubenesque"—in a passage of his novel A Farewell to Arms. Here, two lovers attempt to cross from Italy into Switzerland in the guise of connoisseurs of art. While preparing for their assumed role, they engage in the following exchange: "'Do you know anything about art?' "'Rubens,' said Catherine. "'Large and fat,' I said." Part of the difficulty, it is clear, lies in the American temperament. Historically, we have preferred restraint to exuberance, been uncomfortable with nudes, and admired women who are skinny and twiglike rather than abundant and mature. Moreover, we Americans like art to express private, intensely personal messages, albeit sometimes strange ones, whereas Rubens orchestrated grand public statements, supervised a large workshop and absorbed the efforts of teams of helpers into his own expression. In short, Rubens can appear too excessive, too boisterous and too commercial. In addition, real barriers of culture and At the age of 53, a newly married Rubens celebrated by painting the joyous, nine-foot- background block appreciation. Rubens wide Garden of Love. -

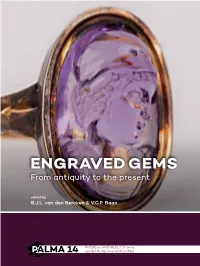

Engraved Gems

& Baan (eds) & Baan Bercken den Van ENGRAVED GEMS Many are no larger than a fingertip. They are engraved with symbols, magic spells and images of gods, animals and emperors. These stones were used for various purposes. The earliest ones served as seals for making impressions in soft materials. Later engraved gems were worn or carried as personal ornaments – usually rings, but sometimes talismans or amulets. The exquisite engraved designs were thought to imbue the gems with special powers. For example, the gods and rituals depicted on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia were thought to protect property and to lend force to agreements marked with the seals. This edited volume discusses some of the finest and most exceptional GEMS ENGRAVED precious and semi-precious stones from the collection of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities – more than 5.800 engraved gems from the ancient Near East, Egypt, the classical world, renaissance and 17th- 20th centuries – and other special collections throughout Europe. Meet the people behind engraved gems: gem engravers, the people that used the gems, the people that re-used them and above all the gem collectors. This is the first major publication on engraved gems in the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden since 1978. ENGRAVED GEMS From antiquity to the present edited by B.J.L. van den Bercken & V.C.P. Baan 14 ISBNSidestone 978-90-8890-505-6 Press Sidestone ISBN: 978-90-8890-505-6 PAPERS ON ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE LEIDEN MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES 9 789088 905056 PALMA 14 This is an Open Access publication.