The Drawing Ezine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Rubens and His Legacy' Exhibition in Focus Guide

Exhibition in Focus This guide is given out free to teachers and full-time students with an exhibition ticket and ID at the Learning Desk and is available to other visitors from the RA Shop at a cost of £5.50 (while stocks last). ‘Rubens I mention in this place, as I think him a remarkable instance of the same An Introduction to the Exhibition mind being seen in all the various parts of the art. […] [T]he facility with which he invented, the richness of his composition, the luxuriant harmony and brilliancy for Teachers and Students of his colouring, so dazzle the eye, that whilst his works continue before us we cannot help thinking that all his deficiencies are fully supplied.’ Sir Joshua Reynolds, Discourse V, 10 December 1772 Introduction Written by Francesca Herrick During his lifetime, the Flemish master Sir Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) For the Learning Department was the most celebrated artist in Europe and could count the English, French © Royal Academy of Arts and Spanish monarchies among his prestigious patrons. Hailed as ‘the prince of painters and painter of princes’, he was also a skilled diplomat, a highly knowledgeable art collector and a canny businessman. Few artists have managed to make such a powerful impact on both their contemporaries and on successive generations, and this exhibition seeks to demonstrate that his Rubens and His Legacy: Van Dyck to Cézanne continued influence has had much to do with the richness of his repertoire. Its Main Galleries themes of poetry, elegance, power, compassion, violence and lust highlight the 24 January – 10 April 2015 diversity of Rubens’s remarkable range and also reflect the main topics that have fired the imagination of his successors over the past four centuries. -

The Spell of Belgium

The Spell of Belgium By Isabel Anderson THE SPELL OF BELGIUM CHAPTER I THE NEW POST THE winter which I spent in Belgium proved a unique niche in my experience, for it showed me the daily life and characteristics of a people of an old civilization as I could never have known them from casual meetings in the course of ordinary travel. My husband first heard of his nomination as Minister to Belgium over the telephone. We were at Beverly, which was the summer capital that year, when he was told that his name was on the list sent from Washington. Although he had been talked of for the position, still in a way his appointment came as a surprise, and a very pleasant one, too, for we had been assured that “Little Paris” was an attractive post, and that Belgium was especially interesting to diplomats on account of its being the cockpit of Europe. After receiving this first notification, L. called at the “Summer White House” in Beverly, and later went to Washington for instructions. It was not long before we were on our way to the new post. Through a cousin of my husband’s who had married a Belgian, the Comte de Buisseret, we were able to secure a very nice house in Brussels, the Palais d’Assche. As it was being done over by the owners, I remained in Paris during the autumn, waiting until the work should be finished. My husband, of course, went directly to Brussels, and through his letters I was able to gain some idea of what our life there was to be. -

Wikimedia with Liam Wyatt

Video Transcript 1 Liam Wyatt Wikimedia Lecture May 24, 2011 2:30 pm David Ferriero: Good afternoon. Thank you. I’m David Ferriero, I’m the Archivist of the United States and it is a great pleasure to welcome you to my house this afternoon. According to Alexa.com, the internet traffic ranking company, there are only six websites that internet users worldwide visit more often than Wikipedia: Google, Facebook, YouTube, Yahoo!, Blogger.com, and Baidu.com (the leading Chinese language search engine). In the States, it ranks sixth behind Amazon.com. Over the past few years, the National Archives has worked with many of these groups to make our holdings increasingly findable and accessible, our goal being to meet the people where they are. This past fall, we took the first step toward building a relationship with the “online encyclopedia that anyone can edit.” When we first began exploring the idea of a National Archives-Wikipedia relationship, Liam Wyatt was one of, was the one who pointed us in the right direction and put us in touch with the local DC-area Wikipedian community. Early in our correspondence, we were encouraged and inspired when Liam wrote that he could quote “quite confidently say that the potential for collaboration between NARA and the Wikimedia projects are both myriad and hugely valuable - in both directions.” I couldn’t agree more. Though many of us have been enthusiastic users of the Free Encyclopedia for years, this was our first foray into turning that enthusiasm into an ongoing relationship. As Kristen Albrittain and Jill James of the National Archives Social Media staff met with the DC Wikipedians, they explained the Archives’ commitment to the Open Government principles of transparency, participation, and collaboration and the ways in which projects like the Wikipedian in Residence could exemplify those values. -

Rubens Was Artist, Scholar, Diplomat--And a Lover of Life

RUBENS WAS ARTIST, SCHOLAR, DIPLOMAT--AND A LOVER OF LIFE An exhibit at Boston's Museum of Fine Arts shows that this Flemish genius truly lived in the right place at the right time by Henry Adams Smithsonian, October, 1993 Of all the great European Old Masters, Rubens has always been the most difficult and puzzling for Americans. Thomas Eakins, the famed American portraitist, once wrote that Rubens' paintings should be burned. Somewhat less viciously, Ernest Hemingway made fun of his fleshy nudes—which have given rise to the adjective "Rubenesque"—in a passage of his novel A Farewell to Arms. Here, two lovers attempt to cross from Italy into Switzerland in the guise of connoisseurs of art. While preparing for their assumed role, they engage in the following exchange: "'Do you know anything about art?' "'Rubens,' said Catherine. "'Large and fat,' I said." Part of the difficulty, it is clear, lies in the American temperament. Historically, we have preferred restraint to exuberance, been uncomfortable with nudes, and admired women who are skinny and twiglike rather than abundant and mature. Moreover, we Americans like art to express private, intensely personal messages, albeit sometimes strange ones, whereas Rubens orchestrated grand public statements, supervised a large workshop and absorbed the efforts of teams of helpers into his own expression. In short, Rubens can appear too excessive, too boisterous and too commercial. In addition, real barriers of culture and At the age of 53, a newly married Rubens celebrated by painting the joyous, nine-foot- background block appreciation. Rubens wide Garden of Love. -

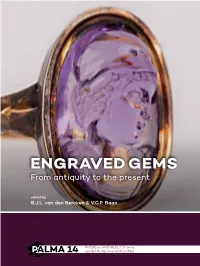

Engraved Gems

& Baan (eds) & Baan Bercken den Van ENGRAVED GEMS Many are no larger than a fingertip. They are engraved with symbols, magic spells and images of gods, animals and emperors. These stones were used for various purposes. The earliest ones served as seals for making impressions in soft materials. Later engraved gems were worn or carried as personal ornaments – usually rings, but sometimes talismans or amulets. The exquisite engraved designs were thought to imbue the gems with special powers. For example, the gods and rituals depicted on cylinder seals from Mesopotamia were thought to protect property and to lend force to agreements marked with the seals. This edited volume discusses some of the finest and most exceptional GEMS ENGRAVED precious and semi-precious stones from the collection of the Dutch National Museum of Antiquities – more than 5.800 engraved gems from the ancient Near East, Egypt, the classical world, renaissance and 17th- 20th centuries – and other special collections throughout Europe. Meet the people behind engraved gems: gem engravers, the people that used the gems, the people that re-used them and above all the gem collectors. This is the first major publication on engraved gems in the collection of the National Museum of Antiquities in Leiden since 1978. ENGRAVED GEMS From antiquity to the present edited by B.J.L. van den Bercken & V.C.P. Baan 14 ISBNSidestone 978-90-8890-505-6 Press Sidestone ISBN: 978-90-8890-505-6 PAPERS ON ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE LEIDEN MUSEUM OF ANTIQUITIES 9 789088 905056 PALMA 14 This is an Open Access publication. -

![Prints That Were Initially Produced and Printed There.[16]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0128/prints-that-were-initially-produced-and-printed-there-16-2070128.webp)

Prints That Were Initially Produced and Printed There.[16]

Peter Paul Rubens (Siegen 1577 – 1640 Antwerp) How to cite Bakker, Piet. “Peter Paul Rubens” (2017). In The Leiden Collection Catalogue, 3rd ed. Edited by Arthur K. Wheelock Jr. and Lara Yeager-Crasselt. New York, 2020–. https://theleidencollection.com/artists/peter-paul- rubens/ (accessed September 27, 2021). A PDF of every version of this biography is available in this Online Catalogue's Archive, and the Archive is managed by a permanent URL. New versions are added only when a substantive change to the narrative occurs. © 2021 The Leiden Collection Powered by TCPDF (www.tcpdf.org) Peter Paul Rubens Page 2 of 7 Peter Paul Rubens was born in Siegen, Germany, on 28 June 1577. His parents were the lawyer Jan Rubens (1530–87) and Maria Pijpelincx (1538–1608).[1] Jan had also been an alderman of Antwerp, but fearing reprisal for his religious tolerance during the Beeldenstorm (Iconoclastic Fury), he fled in 1568 and took refuge with his family in Cologne. There he was the personal secretary of William I of Orange’s (1533–84) consort, Anna of Saxony (1544–77), with whom he had an affair. When the liaison came to light, Jan was banished to prison for some years. Shortly after his death in 1587, his widow returned with her children to Antwerp. Rubens’s study at the Latin school in Antwerp laid the foundations for his later status as a pictor doctus, an educated humanist artist who displayed his erudition not with a pen, but with a paintbrush. He derived his understanding of classical antiquity and literature in part from the ideas of Justus Lipsius (1547–1606), an influential Dutch philologist and humanist.[2] Lipsius’s Christian interpretation of stoicism was a particularly significant source of inspiration for the artist.[3] Rubens’s older brother Filips (1574–1611) had heard Lipsius lecture in Leuven and was part of his circle of friends, as was Peter Paul, who continued to correspond with one another even after the scholar’s death. -

Mines of Misinformation: George Eliot and Old Master Paintings: Berlin, Munich, Vienna and Dresden, 1854-5 and 1858 Leonee Ormond

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln The George Eliot Review English, Department of 2002 Mines of Misinformation: George Eliot and Old Master Paintings: Berlin, Munich, Vienna and Dresden, 1854-5 and 1858 Leonee Ormond Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Literature in English, British Isles Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Ormond, Leonee, "Mines of Misinformation: George Eliot and Old Master Paintings: Berlin, Munich, Vienna and Dresden, 1854-5 and 1858" (2002). The George Eliot Review. 438. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ger/438 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in The George Eliot Review by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. MINES OF MISINFORMATION: GEORGE ELIOT AND OLD MA~TER PAINTINGS: BERLIN, MUNICH, VIENNA AND DRESDEN, 1854-5 AND 1858. By Leonee Onnond This article is a 'footnote' to two classic works on George Eliot: Hugh Witemeyer's George Eliot and the Visual Arts and The Journals of George Eliot, edited by Margaret Harris and Judith Johnston. When I began to follow the progress of George Eliot and George Henry Lewes round the major art galleries of Western Europe, I soon discovered that many of the paintings which George Eliot mentions in her journal were not what she believed them to be. Some have been reattributed since her lifetime, and others, while still bearing the name of the artist she gave them, were not of the subjects she supposed. -

Download PDF Van Tekst

De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 78-79 bron De Gulden Passer. Jaargang 78-79. Vereniging van Antwerpse Bibliofielen, Antwerpen 2000-2001 Zie voor verantwoording: https://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_gul005200001_01/colofon.php Let op: werken die korter dan 140 jaar geleden verschenen zijn, kunnen auteursrechtelijk beschermd zijn. i.s.m. 7 [De Gulden Passer 2000-2001] Woord vooraf Ruim een halve eeuw geleden begon de bibliograaf Prosper Arents aan de realisatie van zijn vermetel plan om de bibliotheek van Pieter Pauwel Rubens virtueel te reconstrueren. In 1961 publiceerde hij in Noordgouw een bondig maar nog steeds lezenswaardig verslag over de stand, op dat ogenblik, van zijn werkzaamheden onder de titel De bibliotheek van Pieter Pauwel Rubens. Toen hij in 1984 op hoge leeftijd overleed, had hij vele honderden titels achterhaald, onderzocht en bibliografisch beschreven. Persklaar kon men zijn notities echter allerminst noemen, iets wat hij overigens zelf goed besefte. In 1994 slaagden Alfons Thijs en Ludo Simons erin onderzoeksgelden van de Universiteit Antwerpen / UFSIA ter beschikking te krijgen om Arents' gegevens electronisch te laten verwerken. Lia Baudouin, classica van vorming, die deze moeilijke en omvangrijke taak op zich nam, beperkte zich niet tot het invoeren van de titels, maar heeft ook bijkomende exemplaren opgespoord, Arents' bibliografische verwijzingen nagekeken en aangevuld en de uitgegeven correspondentie van P.P. Rubens opnieuw gescreend inzake lectuurgegevens. Een informele werkgroep, bestaande uit Arnout Balis, Frans Baudouin, Jacques de Bie, Pierre Delsaerdt, Marcus de Schepper, Ludo Simons en Alfons Thijs, begeleidde L. Baudouin bij haar ‘monnikenwerk’. Na het verstrijken van het mandaat van de onderzoekster bleef toch nog heel wat werk te verrichten om het geheel persklaar te maken. -

9789401453776.Pdf

Met Rubens door Antwerpen 1 RUBENS’ ANTWERP Irene Smets A GUIDE Contents 9 With Rubens through Antwerp 10 Chronological summary of Rubens’ life 12 Rubens and his time 14 Childhood 17 Artistic training and his stay in Italy 22 A future in Antwerp 26 The unfolding of a great talent 34 Protagonist of the Baroque 40 Spectacular productivity - with the help of his workshop 47 Major commissions and international fame 52 A role in European politics 60 The lyrical period 72 Discovering Rubens in Antwerp 75 Royal Museum of Fine Arts in Antwerp 89 Groenplaats 91 Plantin-Moretus Museum 97 Cathedral of Our Lady 110 Grote Markt 113 St. Charles Borromeo Church 119 Snijders & Rockox House 123 The Emperor’s Chapel 125 St. Willibrord’s Church 127 St. Paul’s Church 135 St. Anthony of Padua’s Church 137 St. James’s Church 141 Rubens House Contents 7 8 With Rubens through Antwerp With Rubens through Antwerp Peter Paul Rubens was one of the most important representatives of the art of his time, the Baroque. More than that, he was also one of the most productive artistic geniuses who ever lived. His talents were remarkably varied: in addition to the magnificent religious and mythological canvases for which he is most famous, he also painted landscapes and portraits, as well as making designs for book illustrations, tapestries, buildings and sculptures. He was an outstanding colourist, who raised the skilled use of a rich palette of shades and tints to a new and important form of expression. He also understood the techniques necessary to create dramatic scenes that were capable of seizing and holding the imagination of the viewer. -

RIW 141|04 Presseblätter Engl.Indd

PETER PAUL RUBENS (1577–1640) 28 June 1577 Peter Paul Rubens is born in Siegen in German Westphalia to Jan Rubens and Maria Pypelinckx, the sixth of seven children. His father is a lawyer from Antwerp who had received his training in Italy. In 1568 Jan Rubens is forced to flee with his family to Cologne because of his Calvinist beliefs. He subsequently becomes advisor to Anna of Saxony, the wife of William of Orange. 1587 Following the death of Jan Rubens the family returns to Antwerp. 1588–91 Rubens receives a classical education in Antwerp. 1591 Begins his training as a painter in the studio of his uncle. 1592 Apprenticed to Tobias Verhaeght in Antwerp, afterwards to Adam van Noort. 1594–98 Apprenticed to the Romanist artist Otto van Veen. 1598 Completes his apprenticeship and enters the Guild of St Luke in Antwerp as a master painter. 1598–1600 Works in the studio of Otto van Veen. 1600 Leaves for Italy, becoming court painter to Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga in Mantua. 1601 Arrives in Rome, extensive study of the works of Michelangelo, Titian, Tintoretto and Caravaggio. Entrusted with commissions by the former cardinal Archduke Albert, who had married the Spanish Infanta Isabella in 1599. 1602 In Genoa, Padua and Venice. 1603 Entrusted with a diplomatic mission by the Gonzagas to the Spanish court in Valladolid. 1604/05 In Mantua. 1606 Return to Rome. Lodges there with his brother, Philip, who is also a painter and between 1605 and 1607 was secretary and librarian to Cardinal Ascanio Colonna. 1608 Informed that his mother is gravely ill he returns immediately to Antwerp. -

Corpus Rubenianum Ludwig Burchard

CORPUS RUBENIANUM LUDWIG BURCHARD PART X THE ACHILLES SERIES EGBERT HAVERKAMP BEGEMANN fîl) ARCADE CORPUS RUBENIANUM LUDWIG BURCHARD AN ILLUSTRATED CATALOGUE RAISONNÉ OF THE WORK OF PETER PAUL RUBENS BASED ON THE MATERIAL ASSEMBLED BY THE LATE DR. LUDWIG BURCHARD IN TWENTY-SIX PARTS SPONSORED BY THE CITY OF ANTWERP AND EDITED BY THE “ NATIONAAL CENTRUM VOOR DE PLASTISCHE KUNSTEN VAN DE x v id e EN XVIldeEBUW” R.-A. d’HULST, President - F. BAUDOUIN, Secretary M. DE MAEYER - J . DUVERGER - G. GEPTS - L. LEBEER H. LIEBAERS - J.-K. STEPPE - W. VANBESELAERE SCIENTIFIC ASSISTANCE : N, DE POORTER - P. HUVENNE - C. VAN DE VELDE - H. VLIEGHE THE ACHILLES SERIES EGBERT HAVERKAMP BEGEMANN BRUSSELS-ARCADE PRESS - MCMLXXV NATIONAAL CENTRUM V80R IE PIASTIS2HE KUSTEN VAX IE 169 EN SE 17l EEUW COPYRIGHT IN BRUSSELS, BELGIUM, BY ARCADE PRESS, 19 75 PUBLISHED IN THE UNITED KINGDOM BY PHAIDON PRESS LTD. 5 CROMWELL PLACE, LONDON SW7 2JL PUBLISHED IN THE U.S.A. BY PHAIDON PUBLISHERS INC., NEW YORK DISTRIBUTED IN THE U.S.A. BY PRAEGER PUBLISHERS INC. I l l FOURTH AVENUE, NEW YORK, N.Y. IOOO3 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG CARD NUMBER : 68-21258 ISBN 2-8005-0036-0 complete edition. ISBN 2-8005-0101-4 part X. ISBN 0-7148-1680-9 Phaidon-London. PRINTED IN BELGIUM - LEGAL DEPOSIT D/1975/0721/65 CONTENTS LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS I SOURCES OF PHOTOGRAPHS 5 ABBREVIATIONS 7 AUTHOR’S PREFACE 13 I. THE QUESTIONS OF COMMISSION AND DATE 1 5 II. THE SUBJECT AND ITS SOURCES 20 III. THE OIL SKETCHES 42 IV. THE MODELLI 57 V, THE CARTOONS 67 VI. -

Finnish Politician. Brought up by an Aunt, He Won An

He wrote two operas, a symphony, two concertos and much piano music, including the notorious Minuet in G (1887). He settled in California in 1913. His international reputation and his efforts for his country P in raising relief funds and in nationalist propaganda during World War I were major factors in influencing Paasikivi, Juho Kusti (originally Johan Gustaf President Woodrow *Wilson to propose the creation Hellsen) (1870–1956). Finnish politician. Brought of an independent Polish state as an Allied war up by an aunt, he won an LLD at Helsinki University, aim. Marshal *Piłsudski appointed Paderewski as becoming an inspector of finances, then a banker. Prime Minister and Foreign Minister (1919) and he Finland declared its independence from Russia represented Poland at the Paris Peace Conference and (1917) and Paasikivi served as Prime Minister 1918, signed the Treaty of Versailles (1919). In December resigning when his proposal for a constitutional he retired and returned to his music but in 1939, monarchy failed. He returned to banking and flirted after Poland had been overrun in World War II, with the semi-Fascist Lapua movement. He was he reappeared briefly in political life as chairman of Ambassador to Sweden 1936–39 and to the USSR the Polish national council in exile. 1939–41. World War II forced him to move from Páez, Juan Antonio (1790–1873). Venezuelan conservatism to realism. *Mannerheim appointed liberator. He fought against the Spanish with varying him Prime Minister 1944–46, and he won two success until he joined (1818) *Bolívar and shared terms as President 1946–56.