The Scopophilic Garden from Monet to Mirbeau in His Attempt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

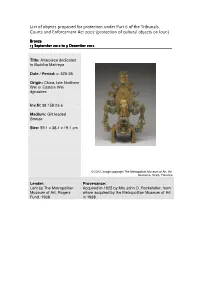

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Altarpiece dedicated to Buddha Maitreya Date / Period: c. 525-35 Origin: China, late Northern Wei or Eastern Wei dynasties Inv.N: 38.158.2a-e Medium: Gilt leaded Bronze Size: 59.1 x 38.1 x 19.1 cm © 2012. Image copyright The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Art Resource, Scala, Florence Lender: Provenance: Lent by The Metropolitan Acquired in 1925 by Mrs John D. Rockefeller, from Museum of Art, Rogers whom acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Fund, 1938 in 1938. List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Apollo Fountain Date / Period: 1532 Artist: Peter Flötner Inv.N: PL 1206/PL 0024 Medium: Brass Size: H. Incl. Base: 100 cm Base: 55 x 55 cm Museen der Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- und Skulpturensammlung Lender: Provenance: Leihgabe der Museen der Commissioned by the archers’ company for their Stadt Nürnberg, Gemälde- shooting yard, Herrenschiesshaus am Sand, und Skulpturensammlung Nuremberg; courtyard of the Pellerhaus. City Museum Fembohaus, Nuremberg (on permanent loan from the city of Nuremberg). List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Bronze 15 September 2012 to 9 December 2012 Title: Avalokiteshvara Date / Period: 9th- 10th century Origin: Java Inv.N: 509 Medium: Silvered Bronze Size: sculpture: 101 x 49 x 28 cm Base: 140 x 47 cm Weight: 250-300kgs Jakarta, Museum Nasional Indonesia Collection/Photo Feri Latief Lender: Provenance: National Museum Discovered in Tekaran, in Surakarta, Indonesia Indonesia (Philip Rawson, The Art of Southeast Asia, London, 1967, pp. -

Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 20 (December 2020), No. 217 Jennifer Forrest, Decadent Aesthetics and the Acrobat in Fin-de-Siècle France. New York: Routledge, 2020. 216 pp. Figures, notes, and index. $160.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 9780367358143; $48.95 U.S. (eb). ISBN 9780429341960. Review by Charles Rearick, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Jennifer Forrest takes us back to a time when many of the artistic avant-garde in Paris frequented the circus and saw acrobatic performances. Her argument in this new book is that innovative writers and artists found much more than images and themes in those popular entertainments. They also found inspiration and models for a new aesthetics, which emerged full-blown in works of the fin-de-siècle movement known as Decadent. First of all, I must say that anyone interested in the subject should not take the title as an accurate guide to this book. The word “acrobat” likely brings to mind a tumbler, tight-rope walker, or trapeze artist, but in Forrest’s account it includes others: the sad clown, the mime, the stock character Pierrot, and the circus bareback rider. The words saltimbanque and funambule (as defined by the author) would cover more of the cast of performers than “acrobat,” though neither French term is quite right for all of them or best for a book in English. The author begins with the year 1857 and a wave of notable works featuring clowns and funambules--works by Théodore de Banville, Honoré Daumier, Charles Baudelaire, Thomas Couture, and Jean-Léon Gérôme. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

The Spell of Belgium

The Spell of Belgium By Isabel Anderson THE SPELL OF BELGIUM CHAPTER I THE NEW POST THE winter which I spent in Belgium proved a unique niche in my experience, for it showed me the daily life and characteristics of a people of an old civilization as I could never have known them from casual meetings in the course of ordinary travel. My husband first heard of his nomination as Minister to Belgium over the telephone. We were at Beverly, which was the summer capital that year, when he was told that his name was on the list sent from Washington. Although he had been talked of for the position, still in a way his appointment came as a surprise, and a very pleasant one, too, for we had been assured that “Little Paris” was an attractive post, and that Belgium was especially interesting to diplomats on account of its being the cockpit of Europe. After receiving this first notification, L. called at the “Summer White House” in Beverly, and later went to Washington for instructions. It was not long before we were on our way to the new post. Through a cousin of my husband’s who had married a Belgian, the Comte de Buisseret, we were able to secure a very nice house in Brussels, the Palais d’Assche. As it was being done over by the owners, I remained in Paris during the autumn, waiting until the work should be finished. My husband, of course, went directly to Brussels, and through his letters I was able to gain some idea of what our life there was to be. -

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011

Copyright by Laura Kathleen Valeri 2011 The Thesis Committee for Laura Kathleen Valeri Certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson Richard A. Shiff Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art by Laura Kathleen Valeri, BA Thesis Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Abstract Rediscovering Maurice Maeterlinck and His Significance for Modern Art Laura Kathleen Valeri, MA The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Linda D. Henderson This thesis examines the impact of Maurice Maeterlinck’s ideas on modern artists. Maeterlinck's poetry, prose, and early plays explore inherently Symbolist issues, but a closer look at his works reveals a departure from the common conception of Symbolism. Most Symbolists adhered to correspondence theory, the idea that the external world within the reach of the senses consisted merely of symbols that reflected a higher, objective reality hidden from humans. Maeterlinck rarely mentioned symbols, instead claiming that quiet contemplation allowed him to gain intuitions of a subjective, truer reality. Maeterlinck’s use of ambiguity and suggestion to evoke personal intuitions appealed not only to nineteenth-century Symbolist artists like Édouard Vuillard, but also to artists in pre-World War I Paris, where a strong Symbolist current continued. Maeterlinck’s ideas also offered a parallel to the theories of Henri Bergson, embraced by the Puteaux Cubists Jean Metzinger and Albert Gleizes. -

Who's Who at the Rodin Museum

WHO’S WHO AT THE RODIN MUSEUM Within the Rodin Museum is a large collection of bronzes and plaster studies representing an array of tremendously engaging people ranging from leading literary and political figures to the unknown French handyman whose misshapen proboscis was immortalized by the sculptor. Here is a glimpse at some of the most famous residents of the Museum… ROSE BEURET At the age of 24 Rodin met Rose Beuret, a seamstress who would become his life-long companion and the mother of his son. She was Rodin’s lover, housekeeper and studio helper, modeling for many of his works. Mignon, a particularly vivacious portrait, represents Rose at the age of 25 or 26; Mask of Mme Rodin depicts her at 40. Rose was not the only lover in Rodin's life. Some have speculated the raging expression on the face of the winged female warrior in The Call to Arms was based on Rose during a moment of jealous rage. Rose would not leave Rodin, despite his many relationships with other women. When they finally married, Rodin, 76, and Rose, 72, were both very ill. She died two weeks later of pneumonia, and Rodin passed away ten months later. The two Mignon, Auguste Rodin, 1867-68. Bronze, 15 ½ x 12 x 9 ½ “. were buried in a tomb dominated by what is probably the best The Rodin Museum, Philadelphia. known of all Rodin creations, The Thinker. The entrance to Gift of Jules E. Mastbaum. the Rodin Museum is based on their tomb. CAMILLE CLAUDEL The relationship between Rodin and sculptor Camille Claudel has been fodder for speculation and drama since the turn of the twentieth century. -

The Library of the Musée National Des Arts Asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France)

Submitted on: June 1, 2013 Museum library and intercultural networking : the library of the Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet (National Museum of Asian Arts, Paris, France) Cristina Cramerotti Library and archives department, Musée national des arts asiatiques Guimet, Paris, France [email protected] Copyright © 2013 by Cristina Cramerotti. This work is made available under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Abstract: The Library and archives department of the musée Guimet possess a wide array of collections: besides books and periodicals, it houses manuscripts, scientific archives – both public and privates, photographic archives and sound archives. From the beginning in 1889, the library is at the core of research and communications with scholars, museums, and various cultural institutions all around the world, especially China, Japan, Korea and Taiwan. We exchange exhibition catalogues and publications dealing with the museum collections, engage in joint editions of its most valuable manuscripts (with China), bilingual editions of historical documents (French and Japanese) and joint databases of photographs (with Japan). Every exhibition, edition or database project requires the cooperation of the two parties, a curator of musée Guimet and a counterpart from the institution we deal with. The exchange is twofold and mutually enriching. Since some years we are engaged in various national databases in order to highlight our collection: a collective library catalogue, the French photographic platform Arago, and of course Joconde, central database maintained by the Ministry of culture which documents the collections of the main French museums. Other databases are available on our website in cooperation with Réunion des musées nationaux, a virtual exposition on early Meiji Japan, and a database of Chinese ceramics. -

Rodin Biography

Contact: Norman Keyes, Jr., Director of Media Relations Frank Luzi, Press Officer (215) 684-7864 [email protected] AUGUSTE RODIN’S LIFE AND WORK François-Auguste-René Rodin was born in Paris in 1840. By the time he died in 1917, he was not only the most celebrated sculptor in France, but also one of the most famous artists in the world. Rodin rewrote the rules of what was possible in sculpture. Controversial and celebrated during his lifetime, Rodin broke new ground with vigorous sculptures of the human form that often convey great drama and pathos. For him, beauty existed in the truthful representation of inner states, and to this end he often subtly distorted anatomy. His genius provided inspiration for a host of successors such as Henri Matisse, Constantin Brancusi and Henry Moore. Unlike contemporary Impressionist Paul Cézanne---whose work was more revered after his death---Rodin enjoyed fame as a living artist. He saw a room in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York dedicated to his work and willed his townhouse in Paris, the Hôtel Biron, to the state as a last memorial to himself. But he was also the subject of intense debate over the merits of his art, and in 1898 he attracted a storm of controversy for his unconventional monument to French literary icon Honoré de Balzac. MAJOR EVENTS IN RODIN’S LIFE 1840 November 12. Rodin is born in Paris. 1854 Enters La Petite École, a special school for drawing and mathematics. 1857 Fails in three attempts to be admitted at the prestigious École des Beaux-Arts. -

Press Kit Shangri-La Hotel, Paris

PRESS KIT SHANGRI-LA HOTEL, PARIS CONTENTS Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat………………………………………………..…….2 Remembering Prince Roland Bonaparte’s Historic Palace………………………………………..4 Shangri-La’s Commitment To Preserving French Heritage……………………………………….9 Accommodations………………………………………………………………………………...12 Culinary Experiences…………………………………………………………………………….26 Health and Wellness……………………………………………………………………………..29 Celebrations and Events………………………………………………………………………….31 Corporate Social Responsibility………………………………………………………………….34 Awards and Talent..…………………………………………………………………….…….......35 Paris, France – A City Of Romance………………………………………………………………40 About Shangri-La Hotels and Resorts……………………………………………………………42 Shangri-La Hotel, Paris – A Princely Retreat Shangri-La Hotel, Paris cultivates a warm and authentic ambience, drawing the best from two cultures – the Asian art of hospitality and the French art of living. With 100 rooms and suites, two restaurants including the only Michelin-starred Chinese restaurant in France, one bar and four historic events and reception rooms, guests may look forward to a princely stay in a historic retreat. A Refined Setting in the Heart of Paris’ Most Chic and Discreet Neighbourhood Passing through the original iron gates, guests arrive in a small, protected courtyard under the restored glass porte cochere. Two Ming Dynasty inspired vases flank the entryway and set the tone from the outset for Asia-meets-Paris elegance. To the right, visitors take a step back in time to 1896 as they enter the historic billiard room with a fireplace, fumoir and waiting room. Bathed in natural light, the hotel lobby features high ceilings and refurbished marble. Its thoughtfully placed alcoves offer discreet nooks for guests to consult with Shangri-La personnel. Imperial insignias and ornate monograms of Prince Roland Bonaparte, subtly integrated into the Page 2 architecture, are complemented with Asian influence in the decor and ambience of the hotel and its restaurants, bar and salons. -

Buddhist Japonisme : Emile Guimet and the Butsuzō-Zui Jérôme Ducor

Buddhist Japonisme : Emile Guimet and the Butsuzō-zui Jérôme Ducor To cite this version: Jérôme Ducor. Buddhist Japonisme : Emile Guimet and the Butsuzō-zui. Japanese Collections in European Museums, Vol. V - With special Reference to Buddhist Art - (JapanArchiv: Schriftenreihe der Forschungstellungsstelle Modernes Japan; Bd. 5, 5., 2016. hal-03154274 HAL Id: hal-03154274 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03154274 Submitted on 28 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. JD / 9 Feb. 2015 EAJS Section 4a: Visual Arts Japanese Buddhist Art in European Collections (Part I) BUDDHIST JAPONISME: EMILE GUIMET AND THE BUTSUZŌ-ZUI Jérôme DUCOR* The nucleus of most collections of Japanese Buddhist artefacts in Europe developed during the Meiji period, which happened to be contemporary with the so-called “Japonism” (or Japonisme) movement in art history. We can therefore say there was at that time a “Buddhist Japonism” trend in Europe. Its most representative figure is Emile Guimet (1836-1918). During his trip in Japan (1876), he collected material items – around 300 paintings, 600 statues, and 1000 volumes of books – most of them made available because of the anti- Buddhist campaign of that time1. -

INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES Visuels Libres De Droit Pour

Sous le Haut Patronage de Sa Majesté Monsieur François Hollande, Preah Bat Samdech Preah Boromneath Président de la République française Norodom Sihamoni Roi du Cambodge INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES Avec le généreux soutien de nos mécènes : la Fondation Total, la Société des Amis du Musée Guimet, NOMURA, l’agence Terre Entière, My Major Company, Thalys et Visuels libres de droit pour la presse dans la période Conférences : VINCI Airports. de l’exposition « Du rêve à la science : le Cambodge de Louis Les visuels sont téléchargeables sur le serveur Delaporte » par Pierre Baptiste, sans réservation En partenariat avec Beaux-Arts magazine, Le Monde, Iliade Productions/ ARTE France, du musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet. préalable, dans la limite des places disponibles. Metronews, A Nous Paris, Télérama, Le Monde des Religions. Adresse : ftp://ftp.guimet.fr <ftp://ftp.guimet.fr/> Billets à retirer aux caisses du musée. Le musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet va remonter aux origines du mythe Utilisateur : ftpcom Lieu de la conférence : Auditorium d’Angkor, tel que l’Europe, et tout particulièrement la France, l’a construit à la fin du Mot de passe : edo009 7 novembre 2013 à 12h15 XIXe siècle et au début du XXe. Cette exposition montrera comment le patrimoine khmer Répertoire : Exposition_Angkor « Angkor aux musées : les moulages du musée a été redécouvert et comment les monuments d’Angkor ont été présentés au public à Musée national des arts asiatiques-Guimet : 6, place indochinois du Trocadéro » par Thierry Zéphir, l’époque des spectaculaires Expositions universelles et coloniales. d’Iéna, 75116 Paris sans réservation préalable, dans la limite des places Issues d’un corpus d’une grande richesse, quelque 250 pièces seront présentées au sein Tel : 01 56 52 53 00 disponibles. -

Vmcent Van Gogh's Published Letters: Mythologizing the Modem Artist

Vmcent van Gogh's Published Letters: Mythologizing the Modem Artist Margaret Fitzgerald Often the study of modem art entails an examination of he became associated with the symbolists. Neo-impres the artist along with his works. This interpretive method sionism and symbolism had in common. above all. their involves the mythology of an a.rtistic temperament from existence as variations of impressionism. They might even which all creative output proceeds. Vincent van Gogh ·s be seen as attempting 10 improve imprc.~sionism by making dramatic life, individual painting style. and expressive it more scientific. on the one hand. and by stressing the correspondence easily lend themselves to such a myth universal Idea over the personal vision. on the other.• The making process. This discussion bricHy outl ines the circum first critics 10 write about van Gogh's art in any depth were stances surrounding tbe pubLication of van Gogh ·s let1ers in symbolist writers. Once this association is made. the the 1890s io order to suggest that a critkal environment categorization persists in the criticism and forms the pre existed ready 10 receive the leucrs in a particular fashion. an dominant interpretation for van Gogh's art works . environment that in tum produced an interpretation for the In the initial issue of the Mercure de France, a paintings. symbolist publication that made its debut in January 1890. TI1roughou1 the 1890s. excerpts from van Gogh ·s Albert Aurier printed an article entitled ''The Isolated Ones: leners 10 his brother Theo and 10 the symbolist painter Vincent van Gogh ..., First in a seric.~ about isolated artists, Emile Bernard were published in the symbolist journal and fonuirously limed, since some of Vincent's works were Mercure de France.