Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heather Buckner Vitaglione Mlitt Thesis

P. SIGNAC'S “D'EUGÈNE DELACROIX AU NÉO-IMPRESSIONISME” : A TRANSLATION AND COMMENTARY Heather Buckner Vitaglione A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of MLitt at the University of St Andrews 1985 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/13241 This item is protected by original copyright P.Signac's "D'Bugtne Delacroix au n6o-impressionnisme ": a translation and commentary. M.Litt Dissertation University or St Andrews Department or Art History 1985 Heather Buckner Vitaglione I, Heather Buckner Vitaglione, hereby declare that this dissertation has been composed solely by myself and that it has not been accepted in any previous application for a higher degree. I was admitted as a candidate for the degree of M.Litt. as of October 1983. Access to this dissertation in the University Library shall be governed by a~y regulations approved by that body. It t certify that the conditions of the Resolution and Regulations have been fulfilled. TABLE---.---- OF CONTENTS._-- PREFACE. • • i GLOSSARY • • 1 COLOUR CHART. • • 3 INTRODUCTION • • • • 5 Footnotes to Introduction • • 57 TRANSLATION of Paul Signac's D'Eug~ne Delac roix au n~o-impressionnisme • T1 Chapter 1 DOCUMENTS • • • • • T4 Chapter 2 THE INFLUBNCB OF----- DELACROIX • • • • • T26 Chapter 3 CONTRIBUTION OF THE IMPRESSIONISTS • T45 Chapter 4 CONTRIBUTION OF THB NEO-IMPRBSSIONISTS • T55 Chapter 5 THB DIVIDED TOUCH • • T68 Chapter 6 SUMMARY OF THE THRBE CONTRIBUTIONS • T80 Chapter 7 EVIDENCE • . • • • • • T82 Chapter 8 THE EDUCATION OF THB BYE • • • • • 'I94 FOOTNOTES TO TRANSLATION • • • • T108 BIBLIOGRAPHY • • • • • T151 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS Plate 1. -

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series Editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University

The Total Work of Art in European Modernism Series editor: Peter Uwe Hohendahl, Cornell University Signale: Modern German Letters, Cultures, and Thought publishes new English- language books in literary studies, criticism, cultural studies, and intellectual history pertaining to the German-speaking world, as well as translations of im- portant German-language works. Signale construes “modern” in the broadest terms: the series covers topics ranging from the early modern period to the present. Signale books are published under a joint imprint of Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library in electronic and print formats. Please see http://signale.cornell.edu/. The Total Work of Art in European Modernism David Roberts A Signale Book Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Ithaca, New York Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library gratefully acknowledge the support of The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation for the publication of this volume. Copyright © 2011 by Cornell University All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in a review, this book, or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writ- ing from the publisher. For information, address Cornell University Press, Sage House, 512 East State Street, Ithaca, New York 14850. First published 2011 by Cornell University Press and Cornell University Library Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Roberts, David, 1937– The total work of art in European modernism / David Roberts. p. cm. — (Signale : modern German letters, cultures, and thought) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-8014-5023-5 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Modernism (Aesthetics) 2. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/04/2021 08:07:20AM This Is an Open Access Chapter Distributed Under the Terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 License

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL FOR HISTORY, CULTURE AND MODERNITY www.history-culture-modernity.org Published by: Uopen Journals Copyright: © The Author(s). Content is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence eISSN: 2213-0624 L’Art pour l’Art or L’Art pour Tous? The Tension Between Artistic Autonomy and Social Engagement in Les Temps Nouveaux, 1896–1903 Laura Prins HCM 4 (1): 92–126 DOI: 10.18352/hcm.505 Abstract Between 1896 and 1903, Jean Grave, editor of the anarchist journal Les Temps Nouveaux, published an artistic album of original prints, with the collaboration of (avant-garde) artists and illustrators. While anar- chist theorists, including Grave, summoned artists to create social art, which had to be didactic and accessible to the working classes, artists wished to emphasize their autonomous position instead. Even though Grave requested ‘absolutely artistic’ prints in the case of this album, artists had difficulties with creating something for him, trying to com- bine their social engagement with their artistic autonomy. The artistic album appears to have become a compromise of the debate between the anarchist theorists and artists with anarchist sympathies. Keywords: anarchism, France, Neo-Impressionism, nineteenth century, original print Introduction While the Neo-Impressionist painter Paul Signac (1863–1935) was preparing for a lecture in 1902, he wrote, ‘Justice in sociology, har- mony in art: same thing’.1 Although Signac never officially published the lecture, his words have frequently been cited by scholars since the 1960s, who claim that they illustrate the widespread modern idea that any revolutionary avant-garde artist automatically was revolutionary in 92 HCM 2016, VOL. -

Perceptions on the Starry Night

Kay Sohini Kumar To the Stars and Beyond: Perceptions on The Starry Night “The earliest experience of art must have been that it was incantatory, magical; art was an instrument of ritual. The earliest theory of art, that of Greek philosophers, proposed that art was mimesis, imitation of reality...even in the modern times, when most artists and critics have discarded the theory of art as representation of an outer reality in favor of theory of art as subjective expression, the main feature of the mimetic theory persists” (Sontag 3-4) What is it like to see the painting, in the flesh, that you have been worshipping and emulating for years? I somehow always assumed that it was bigger. The gilded frame enclosing The Starry Night at the Museum of Modern Art occupies less than a quarter of the wall it is hung upon. I had also assumed that there would be a bench from across the painting, where I could sit and gaze at the painting intently till I lost track of time and space. What I did not figure was how the painting would only occupy a tiny portion of the wall, or that there would be this many people1, that some of those people would stare at me strangely (albeit for a fraction of a second, or maybe I imagined it) for standing in front of The Starry Night awkwardly, with a notepad, scribbling away, for so long that it became conspicuous. I also did not expect how different the actual painting would be from the reproductions of it that I was used to. -

1 Tomasz Dziewicki University of Warsaw Intensivism As a Tool of An

III. International Forum for doctoral candidates in East European art history, Berlin, 29th April 2016, organized by the Chair of Art History of Eastern and East Central Europe, Humboldt University Berlin Tomasz Dziewicki University of Warsaw XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Intensivism as a Tool of an Art Historian In 1897 in Warsaw, the art critic, Cezary Jellenta, published in a weekly magazine "Głos" the article titled Intensivism. This article in its times did not influence on a polish art, but nowadays a category of intensivism created by Jellenta can be seen as an useable tool from the point of view a art historian. Jellenta noticed in his article a new trend in painting of the end of the century. In his mind modern art turned to a subjective way of perception of reality. Presentation of ordinary objects and phenomena, which are known by a viewer, in work of art tends to experience them anew. The art critic maintained a role of personal experience of powers of nature through a painting and the fact that this power may be embodied with the soul of an artist. At the beginning of his paper he refered to anachronistic examples of Andreas Achenbach's and Anders Zorn's work but also pointed out Arnold Böcklin, Władysław Podkowiński or Józef Pankiewicz as founders of the new movement. Jellenta paid attention to a modern composition, simplification and painting synthesis, which enable to express reality better and deeper. He applies a category, separated plastically and semantically from a representation, of main motif , which, as Jellenta wrote, "tunes our soul". In fact it is an attempt to transfer the music theory of Leitmotif by Richard Wagner on the ground of the painting. -

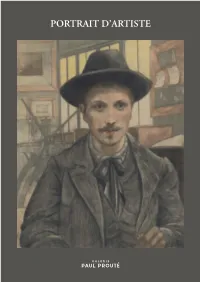

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

Memoir of Vincent Van Gogh Free Download

MEMOIR OF VINCENT VAN GOGH FREE DOWNLOAD Van Gogh-Bonger Jo,Jo Van Gogh-Bonger | 192 pages | 01 Dec 2015 | PALLAS ATHENE PUBLISHERS | 9781843681069 | English | London, United Kingdom BIOGRAPHY NEWSLETTER Memoir of Vincent van Gogh save with free shipping everyday! He discovered that the dark palette he had developed back in Holland was hopelessly out-of-date. At The Yellow Housevan Gogh hoped like-minded artists could create together. On May 8,he began painting in the hospital gardens. Almond Blossom. The search for his own idiom led him to experiment with impressionist and postimpressionist techniques and to study the prints of Japanese masters. Van Gogh was a serious and thoughtful child. Born into an upper-middle-class family, Van Gogh drew as a child and was serious, quiet, and thoughtful. It marked the beginning of van Dyck's brilliant international career. Van Gogh: the Complete Paintings. See Article History. Vincent to Theo, Nuenen, on or about Wednesday, 28 October Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Van Gogh und die Haager Schule. Archived from the original on 22 September The first was painted in Paris in and shows flowers lying on the ground. Sold to Anna Boch Auvers-sur-Oise, on or about Thursday, 10 July ; Rosenblum Wheat Field with Cypresses Athabasca University Press. The 14 paintings are optimistic, joyous and visually expressive of the burgeoning spring. Van Gogh then began to alternate between fits of madness and lucidity and was sent to the asylum in Saint-Remy for treatment. Van Gogh learned about Fernand Cormon 's atelier from Theo. -

Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1

H-France Review Volume 20 (2020) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 20 (December 2020), No. 217 Jennifer Forrest, Decadent Aesthetics and the Acrobat in Fin-de-Siècle France. New York: Routledge, 2020. 216 pp. Figures, notes, and index. $160.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 9780367358143; $48.95 U.S. (eb). ISBN 9780429341960. Review by Charles Rearick, University of Massachusetts, Amherst. Jennifer Forrest takes us back to a time when many of the artistic avant-garde in Paris frequented the circus and saw acrobatic performances. Her argument in this new book is that innovative writers and artists found much more than images and themes in those popular entertainments. They also found inspiration and models for a new aesthetics, which emerged full-blown in works of the fin-de-siècle movement known as Decadent. First of all, I must say that anyone interested in the subject should not take the title as an accurate guide to this book. The word “acrobat” likely brings to mind a tumbler, tight-rope walker, or trapeze artist, but in Forrest’s account it includes others: the sad clown, the mime, the stock character Pierrot, and the circus bareback rider. The words saltimbanque and funambule (as defined by the author) would cover more of the cast of performers than “acrobat,” though neither French term is quite right for all of them or best for a book in English. The author begins with the year 1857 and a wave of notable works featuring clowns and funambules--works by Théodore de Banville, Honoré Daumier, Charles Baudelaire, Thomas Couture, and Jean-Léon Gérôme. -

Gala2o2o Saturday, October 17

VIRTUAL GALA2O2O SATURDAY, OCTOBER 17 THANK YOU FOR YOUR SUPPORT AND FOR JOINING US THIS EVENING Dear Friends, Welcome to the (very unusual and hopefully unique) 17th annual Reach for the Stars Gala! Six months ago, it was unthinkable that we would not be gathering together to celebrate tonight. We envisioned the ballroom, the tables, the speakers, and the dancing. Now it is up to you to take a spin at home. Right now, advocates are talking with survivors, assisting with paperwork, safety planning, and counseling them as they face an (even more) uncertain future. Right now, our prevention staff is working with teachers, coaches, and administrators on professional development programs, classroom presentations, team trainings, and parent meetings. Right now, our house is home to only half of the families we are sheltering—four families remain in a hotel after fully emptying the shelter when COVID hit. We clean like never before and advocate like we always have—in a world that looks so different. And as you read this, right now, we are getting ready to host a virtual gala for the first time. We are excited to share this evening with hundreds of people over the internet, something we never envisioned when we planned it. We are doing this with your help and our shared conviction that the show must go on because the work goes on. When our office lights went out on March 16, dozens of makeshift desks got set up. Cell phones got charged. We kept working. REACH staff kept calling survivors, partnering with schools, providing shelter—we kept doing it all. -

Art Planning Based on Pointillism

Maintaining and supporting your child’s learning during school closure Dear Parents / Carers, Thank you for the work done so far and encouraging the children to keep up with it in such difficult circumstances. We know you will all be doing your very best. Below is an outline of some Art planning based on Pointillism. Keep safe and stay in touch. Kind Regards, The Year 3 Team Art Mon Georges Seurat 08.06.21 Read through the PowerPoint about Georges Seurat. If you cannot access the PowerPoint, use a computer/iPad to research Georges Seurat. Tues Pointillism 09.06.21 Read through the PowerPoint about Pointillism. If you cannot access the PowerPoint, use a computer/iPad to research Pointillism. Choose one artist from the following: Georges Seurat, Paul Signac, Maximillian Luce or Charles Angrand and complete the sheet: Pointillism Painter Fact File. You will need access to a computer/iPad so you can research them on the internet. Make sure you choose an artist because you love their artwork. You will be using this artist as inspiration over the next couple of weeks. Wed Pointillism techniques 10.06.21 Watch the video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dyapH_yAPQ, which teaches Pointillism techniques of shading and blending, using felt tip pens and paint. Once you have watched the video, have a go at experimenting with both techniques. If you do not have cotton buds, you could use the end of a paintbrush or pencil. It would be great to see your experimentations so ask your parent or carer to send us a picture of your work via the Year 3 email. -

Download Text

SUM, CONVENT OF ST AGNES, NATIONAL GALLERY PRAGUE, PRAGUE, CZECH REPUBLIC, 2018 Antony Gormley's passion is to ask whether a human form - as both a vessel for the body and a container for the mind - can be a contemporary subject for contemplation; questions that are essentially spiritual. Gormley speaks of "being" in its widest context, exploring the now. He works with life, making body moulds and body casts, by implication life-size, in various subtle, undramatic states, and places them in a range of settings. These locations are never random; Gormley selects them for their associations. He treats the body as a house and invites the viewer's participation. For Gormley: "How the sculptures are disposed in space is perhaps more important than what they represent." ['Vessel', Antony Gormely, Galeria Continua, San Gimignano, 2012, p.42] This thinking is relevant for the works installed at the Convent of St Agnes, founded at the beginning of the 13th century and situated at the edge of the Old Town. The Church of St Salvator, the earliest Gothic building in Prague and the oldest part of this magnificent historical space, is the perfect site for the 'Reflections' series, in which contemporary art will be seen in a context that speaks to the uniqueness of both art and architecture. The viewer is left alone to reflect. Antony Gormley's two works on paper - the woodcut REACH (2016) and the imprint FEEL (2016) - resonate with the cast iron sculpture SUM (2012), the show's central motif. "Sum" in Latin stands for "I am" in English, or "being", the title of this show. -

Les Arnajons (Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade, Bouches

Les Arnajons (Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade, Bouches-du-Rhône) : un nouveau dolmen dans le Sud-Est de la France Jean-Philippe Sargiano, André d’Anna, Céline Bressy-Leandri, Jessie Cauliez, Muriel Pellissier, Hugues Plisson, Stéphane Renault, Anne Richier, Olivier Sivan, Philippe Chapon To cite this version: Jean-Philippe Sargiano, André d’Anna, Céline Bressy-Leandri, Jessie Cauliez, Muriel Pellissier, et al.. Les Arnajons (Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade, Bouches-du-Rhône) : un nouveau dolmen dans le Sud-Est de la France. Préhistoires Méditerranéennes, Association pour la promotion de la préhistoire et de l’anthropologie méditerranéennes, 2010, 1, pp.1-37. halshs-00584981 HAL Id: halshs-00584981 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00584981 Submitted on 11 Apr 2011 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Préhistoires méditerranéennes 1 — 2010 — @1-37 Disponible en ligne / Available online pm.revues.org Les Arnajons (Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade, Bouches-du-Rhône) : un nouveau dolmen dans le Sud-Est de la France Les Arnajons (Le-Puy-Sainte-Réparade, Bouches-du-Rhône) : a new long chambered tomb of south-east France Jean Philippe Sargiano (dir.)1, André D’Anna (dir.)2 Céline Bressy2, Jessie Cauliez3, Muriel Pellissier2, Hugues Plisson4, Stéphane Renault2, Anne Richier5, Olivier Sivan6 et Philippe Chapon7 Résumé Un nouveau dolmen a été découvert dans les Bouches-du-Rhône à l’occasion de prospections et sondages réalisés par l’Inrap.