Adolphe Monticelli, Subject Composition (NG 5010), Reverse, Probably 1870–86 (Detail)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

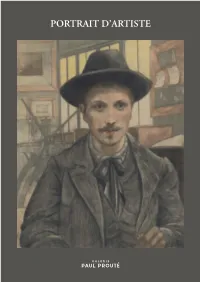

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995

Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995 bron Van Gogh Museum Journal 1995. Waanders, Zwolle 1995 Zie voor verantwoording: http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/_van012199501_01/colofon.php © 2012 dbnl / Rijksmuseum Vincent Van Gogh 6 Director's Foreword The Van Gogh Museum shortly after its opening in 1973 For those of us who experienced the foundation of the Van Gogh Museum at first hand, it may come as a shock to discover that over 20 years have passed since Her Majesty Queen Juliana officially opened the Museum on 2 June 1973. For a younger generation, it is perhaps surprising to discover that the institution is in fact so young. Indeed, it is remarkable that in such a short period of time the Museum has been able to create its own specific niche in both the Dutch and international art worlds. This first issue of the Van Gogh Museum Journal marks the passage of the Rijksmuseum (National Museum) Vincent van Gogh to its new status as Stichting Van Gogh Museum (Foundation Van Gogh Museum). The publication is designed to both report on the Museum's activities and, more particularly, to be a motor and repository for the scholarship on the work of Van Gogh and aspects of the permanent collection in broader context. Besides articles on individual works or groups of objects from both the Van Gogh Museum's collection and the collection of the Museum Mesdag, the Journal will publish the acquisitions of the previous year. Scholars not only from the Museum but from all over the world are and will be invited to submit their contributions. -

INTRODUCTION: the Letters of Van Gogh

g. In Paris e - _ew in the way o: · -e · cussed them 1 ang companio • · e in Paris he troversial of he Vincent van Gogh, self-portraits from a - ose personal con letter of March r886. - essity to write do ~ d. So, in Arles e on on the theories d ool, pale tones of·' ch colors of the o: • rints, and they o=-e ·sons he had learn For all of ·' INTRODUCTION: The Letters of Van Gogh onths at Arles, w ovements into his The statements by Van Gogh specifically concerned with his ideas and · oughts of his frien theories on art are not numerous, and are most often very simple and direct. Octo her, he "\.Vas .. They occur almost exclusively during a very brief period, the first few differences and co -" · fruitful and idyllic months when, having just left Paris at the age of thirty- · at put an end to t' · 1five, he settled in Ades for a stay that lasted from February 1888 until May Most of the l 889. There are several reasons why these ideas and theories should have "incent' s younger b: appeared in his letters at this particular time and for so brief a period. · e art dealers, Gou · He enjoyed at Ades, for the first time in two years, a solitude which · rather and his under he sorely needed, and which he had been unable to achieve in Paris, where =he letters. When Y he had lived with his brother Theo and had associated with artists in the '-lrged him to become studios and cafes of Montmartre. -

Les Belles Expositions De La Rentree 2018 Region Paca

LES BELLES EXPOSITIONS DE LA RENTREE 2018 REGION PACA : Pour l’été beaucoup d’expositions se mettent en place en ce moment, vérifiez bien les dates d’ouverture et de fermeture. Cet été vous n’échapperez pas aux thèmes de l’Amour et de Picasso, le premier se conjuguant allègrement dans l’œuvre du second, le « Minotaure amoureux » que fut ce génie du XX e siècle. AIX EN PROVENCE (13) : 6 OCCASIONS DE VOIR PICASSO EN PROVENCE : jusqu’au 6 janvier 2019 : En 2018, profitez d'une offre culturelle exceptionnelle et d'un parcours dans la création de Picasso en découvrant 6 expositions présentant un ensemble remarquable de ses oeuvres. De la Vieille Charité à Marseille, en passant par le Mucem, l'Hôtel de Caumont, le musée Matisse, la Fondation Van Gogh, le Musée Granet , mais aussi jusqu'aux Carrières de Lumières et au Musée Fabre à Montpellier toute la Provence méditerranéenne célèbre Picasso. Grâce à « Picasso-Méditerranée », une manifestation culturelle internationale organisée de 2017 à 2019, plus de soixante institutions ont imaginé ensemble une programmation autour de l’oeuvre «obstinément méditerranéenne» de Pablo Picasso. À l’initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris, ce parcours dans la création de l’artiste et dans les lieux qui l’ont inspiré offre une expérience culturelle inédite, souhaitant resserrer les liens entre toutes les rives. En Provence, c'est l'Hôtel de Caumont à Aix-en-Provence qui a ouvert le bal avec une superbe exposition Botero dialogue avec Picasso qui présente la riche production du maître colombien sous un angle inédit et qui explore ses affinités artistiques avec Pablo Picasso, elle est maintenant fermée depuis le 11 mars. -

MAKING VAN GOGH a GERMAN LOVE STORY 23 OCTOBER 2019 to 16 FEBRUARY 2020 Städel Museum, Garden Halls

WALL TEXTS MAKING VAN GOGH A GERMAN LOVE STORY 23 OCTOBER 2019 TO 16 FEBRUARY 2020 Städel Museum, Garden Halls INTRODUCTION With the exhibition “MAKING VAN GOGH: A German Love Story”, the Städel Museum is devoting itself to one of the most well-known artists of all times and his special relationship to Germany. Particularly in this country, Vincent van Gogh’s works have been greatly appreciated since his death. Thanks to the dedication of gallerists, collectors, critics and museum directors, the Dutch artist came to be known here as one of the early twentieth century’s most important pioneers of modern painting. Numerous private collectors and museums purchased his works. By 1914, there were some 150 works by Van Gogh in German collections. The show is an endeavour to get to the bottom of this phenomenon. How did Van Gogh manage to attain such tremendous popularity before World War I in Germany, of all places? Who promoted his art? How did German artists react to him soon after the turn of the century? The exhibition takes a closer look at these matters in three main sections that shed light on the emergence of the legend surrounding Vincent van Gogh as a person, his influence on the German art world, and finally the exceptional painting style that held such a strong fascination for many of his followers. IMPACT The growing presence of Van Gogh’s works in exhibitions and collections in Germany also had an impact on the artists here. Many of them reacted enthusiastically to their encounters with his paintings and drawings. -

Nordic Painting: the Rise of Modernity Pdf, Epub, Ebook

NORDIC PAINTING: THE RISE OF MODERNITY PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Katharina Alsen | 272 pages | 18 Nov 2016 | PRESTEL | 9783791381312 | English | Munich, Germany Nordic Painting: The Rise of Modernity PDF Book Sarah C. Modernity will have a busy and exciting agenda with seven high end international art and design fairs in Europe and the United States. Add to Wish List Compare this Product. To reach the boarding ladder, we had to go around the stern. Spring Volume 16, Issue 1. The Museum of Modern Art MoMA in New York City , the outstanding public collection in the field, was founded in , and the Western capital that lacks a museum explicitly devoted to modern art is rare. Learn more - opens in a new window or tab. The term stratigraphy, however, also has a second meaning, related to the scholarly approach here adopted. It tells the story of how Andrew became an Expat and about life as a dealer of 20th century Scandinavian design, living in Stockholm and in having a country home by the sea. Add to Watchlist. Another possibility of Romanticism was pursued in isolation by the Marseille painter Adolphe Monticelli. Roberto C. Chronicle Books. Flame Tree Publishing. Tragedy of Childhood , His wife, in turn, rapidly dresses up again, adorned with a coat and a hat in panther furs the pearls vanish, replaced by earrings and a glove. La moglie a sua volta si riveste rapidamente, per mostrarsi in pelliccia e berretto di pantera e via le perle dal collo per mettersi gli orecchini ed infilarsi un guanto. De Chirico, similarly, makes their recognizable elements collapse into their own subsequent genealogical elaborations, creating a mixture that cannot be traced back to a single positive origin. -

Disponible Ici En Téléchargement

Archives départementales et conservation des antiquités et objets d'art des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence 2017 Catalogue de l’exposition présentée à la cathédrale Saint-Jérôme à Digne-les-Bains du 7 juillet au 30 septembre 2017 Commissariat Jean-Christophe Labadie, directeur des Archives départementales et conservateur des antiquités et objets d’art des Alpes-de-Haute- Provence Laure Franek, directrice adjointe des Archives départementales Marie-Christine Braillard, conservateur territorial en chef du patrimoine honoraire Frère Régis Blanchard, abbaye de Ganagobie Textes, choix des illustrations et notices Frère Régis Blanchard Laure Franek Jean-Christophe Labadie Nicole Michel d’Annoville Gestion des oeuvres Claude Badet, conservateur délégué des antiquités et objets d’art des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence Pascal Boucard (Archives départementales) Montage de l’exposition Pascal Boucard, Pierre Chaland, Denis Élie, Jean-Claude Paglia (Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence) Conception graphique du catalogue Jean-Marc Delaye (Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence) Crédits photographiques et numérisation Jean-Marc Delaye (Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute- Provence) Relecture Annie Massot, bibliothécaire, (Archives départementales des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence) Les commissaires de l'exposition remercient particulièrement Patrick Palem, directeur de la SOCRA (Périgueux), pour son aide et sa généreuse disponibilité. Impression Imprimerie de Haute-Provence 04700 La Brillanne ISBN 978-2-86004-034-1 © Conseil départemental des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence Dépôt légal : juillet 2017 et ses mosaïques du XIIe siècle 2 a fortune a souri au département des Alpes-de-Haute-Provence car son territoire est riche d’un trésor ! Et quel trésor : des mosaïques posées vers 1125 sur le sol du chœur de l’église Ldu monastère de Ganagobie, un établissement fondé au milieu du Xe siècle par l’évêque de Sisteron. -

And Its Artists 4

and its artists 4 4.1 Artists in Cassis Cassis has long attracted artists, especially painters. In fact, they cannot all be listed as there are no documentary descriptions of their visits here. The Municipal Museum in Cassis has no works by the Fauvists for example but it has a fairly extensive collection of works by their contemporaries. Locals from Marseille and elsewhere in Provence such as Marius and Eugénie CassisGU INDaON, Rnené SEdYSSA UD,i Matthiesu VER DILaHAN, rRAVAtISONi asnd Chtarles s CAMOIN were all regular visitors. There was also MANGUIN, who stayed at the Villecroze Estate on several occasions. Paul SIGNAC discovered Cassis and Cape Canaille while sailing his yacht and painted them in 1889 on a can - vas that is now famous, before continuing eastwards to Saint-Tropez. The others, Francis PICABIA, Georges BRAQUE, Othon FRIESZ, André DERAIN, Maurice VLAMINCK, KISLING, Raoul DUFY and VARDA came to Cassis but we have no details about their stay here. However, their names should be enough to underline the undeniable attraction of Cassis for these great artists. La Calanque (1906) seen by Paul SIGNAC. Here are just a few paintings linked to Cassis: André DERAIN , Les Cyprès, Paysage à Cassis, Pinède à Cassis, 1907 Paul SIGNAC , Pointe des Lombards, 1889, Museum in the Haye Edouard CREMIEUX , Cassis vu de l'ancien chemin des Lombards, 1936 Joseph GARIBALDI , Vue de Cassis, 1897, Museum & Art Gallery in Marseille Jean-Baptiste OLIVE , La calanque d'En Vau, 1936 Charles-Henri PERSON , La Calanque, 1912 Luc Raphaël PONSON , La Calanque -

Exhibitions Paul Nash Hot Sun, Late

Communication and press relations: PIERRE COLLET | IMAGINE T +33 1 40 26 35 26 M +33 6 80 84 87 71 [email protected] ALICE PROUVÉ | IMAGINE M +06 71 47 16 33 [email protected] EXHIBITIONS 21.04 – 28.10.2018 Press preview: Friday 20 April 2018 at 1pm HOT SUN, PAUL NASH SUNFLOWER RISES LATE SUN Vincent van Gogh, Harvest in Provence, June 1888 Paul Nash, Solstice of the Sunflower, 1945 Oil on canvas, 51 x 60 cm Oil on canvas, 71.3 x 91.4 cm Israel Museum, Jerusalem National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa FONDATION VINCENT VAN GOGH ARLES – PRESS RELEASE EDITORIAL Since its inauguration in 2014, the Fondation Vincent van Gogh Arles has presented works by the great masters of painting—foremost among them being Vincent van Gogh, whose work underpins the direction of our program. However, while Vincent will be present once again, this upcoming exhibition is driven by the work of another great painter in modern art, Pablo Picasso. Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh: an extraordinary dialogue delving into the major influence of the Dut- ch painter on Picasso, who considered him the “greatest of all”; just this would have sufficed. But Hot Sun, Late Sun is a thematic exhibition, weaving an intricate conversation highlighting the intersections between practices— between Pablo Picasso and Sigmar Polke for one, but also between Alexander Calder, Adolphe Monticelli, Giorgio de Chirico and Vincent van Gogh. Hot Sun, Late Sun will feature a number of rare loans, which we are proud to present to the public over a six-month period. -

Etablissement Exceptionnel Favorable Collège Adolphe Monticelli

Sans Très Total des Etablissement Exceptionnel Favorable opposition favorable promouvables Collège Adolphe Monticelli Marseille 8e 1 7 3 3 14 Collège Alain Savary Istres 14 6 20 Collège Albert Camus La Tour-d'Aigues 5 3 1 13 22 Collège Albert Camus Miramas 1 16 1 18 Collège Alphonse Daudet Carpentras 3 2 3 9 17 Collège Alphonse Daudet Istres 10 2 2 14 Collège Alphonse Silve Monteux 7 5 5 17 Collège Alphonse Tavan Avignon 12 4 6 22 Collège Ampère Arles 6 7 5 18 Collège Anatole France Marseille 6e 1 2 1 5 9 Collège André Chénier Marseille 12e 2 3 2 11 18 Collège André Honnorat Barcelonnette 2 6 5 13 Collège André Malraux Fos-sur-Mer 3 6 4 13 Collège André Malraux Marseille 13e 6 9 1 5 21 Collège André Malraux Mazan 4 10 1 7 22 Collège Anselme Mathieu Avignon 3 3 1 4 11 Collège Apt 5 9 12 26 Collège Arausio Orange 2 4 1 9 16 Collège Arc de Meyran Aix-en-Provence 8 2 1 14 25 Collège Arenc Bachas Marseille 15e 2 4 1 7 Collège Arthur Rimbaud Marseille 15e 1 1 2 4 Collège Auguste Renoir Marseille 13e 3 4 7 Collège Barbara Hendricks Orange 3 3 11 17 Collège Belle de Mai Marseille 3e 3 5 4 12 Collège Camille Claudel Vitrolles 1 2 4 7 Collège Camille Reymond Château-Arnoux-Saint-Auban 1 8 1 7 17 Collège Campagne Fraissinet Marseille 5e 2 4 4 10 Collège Campra Aix-en-Provence 5 5 11 21 Collège Centre Gap 6 7 2 5 20 Collège Chape Marseille 4e 2 6 3 11 Collège Charles Doche Pernes-les-Fontaines 4 7 3 13 27 Collège Charles Rieu Saint-Martin-de-Crau 8 13 2 23 Collège Château Double Aix-en-Provence 5 4 3 12 24 Collège Château Forbin Marseille 11e 1 14 -

Souvenirs and Fêtes Champêtres: William Allan Coats’S

Edinburgh Research Explorer Souvenirs and Fêtes Champêtres: William Allan Coats’s Collection of Nineteenth-Century French Paintings Citation for published version: Fowle, F 2009, 'Souvenirs and Fêtes Champêtres: William Allan Coats’s Collection of Nineteenth-Century French Paintings', Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History, vol. 14, pp. 63-70. <http://www.dundee.ac.uk/museum/ssah/backcopies.html> Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History Publisher Rights Statement: © Fowle, F. (2009). Souvenirs and Fêtes Champêtres: William Allan Coats’s Collection of Nineteenth-Century French Paintings. Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History, 14, 63-70. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Souvenirs and Fêtes Champêtres: William Allan Coats’s Collection of 19th-Century French Paintings Frances Fowle n 1889 Andrew Carnegie warned that ‘the Nevertheless William deserves to be man who dies leaving behind him millions remembered for his magnificent art collection, Iof available wealth, which was his to ad- now widely dispersed.