Studies in the History of Collecting & Art Markets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus

Celticism, Internationalism and Scottish Identity Three Key Images in Focus Frances Fowle The Scottish Celtic Revival emerged from long-standing debates around language and the concept of a Celtic race, a notion fostered above all by the poet and critic Matthew Arnold.1 It took the form of a pan-Celtic, rather than a purely Scottish revival, whereby Scotland participated in a shared national mythology that spilled into and overlapped with Irish, Welsh, Manx, Breton and Cornish legend. Some historians portrayed the Celts – the original Scottish settlers – as pagan and feckless; others regarded them as creative and honorable, an antidote to the Industrial Revolution. ‘In a prosaic and utilitarian age,’ wrote one commentator, ‘the idealism of the Celt is an ennobling and uplifting influence both on literature and life.’2 The revival was championed in Edinburgh by the biologist, sociologist and utopian visionary Patrick Geddes (1854–1932), who, in 1895, produced the first edition of his avant-garde journal The Evergreen: a Northern Seasonal, edited by William Sharp (1855–1905) and published in four ‘seasonal’ volumes, in 1895– 86.3 The journal included translations of Breton and Irish legends and the poetry and writings of Fiona Macleod, Sharp’s Celtic alter ego. The cover was designed by Charles Hodge Mackie (1862– 1920) and it was emblazoned with a Celtic Tree of Life. Among 1 On Arnold see, for example, Murray Pittock, Celtic Identity and the Brit the many contributors were Sharp himself and the artist John ish Image (Manchester: Manches- ter University Press, 1999), 64–69 Duncan (1866–1945), who produced some of the key images of 2 Anon, ‘Pan-Celtic Congress’, The the Scottish Celtic Revival. -

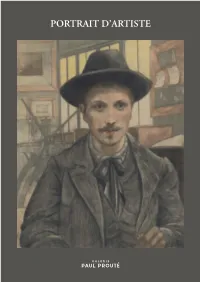

Portrait D'artiste

<--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------><- 15 mm -><--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 210 mm ---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------> 2020 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 74, rue de Seine — 75006 Paris Tél. — + 33 (0)1 43 26 89 80 e-mail — [email protected] www.galeriepaulproute.com PAUL PROUTÉ GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 1 30/10/2020 16:15:36 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 1920 2020 GPP_Portaits_oct2020_CV.indd 2 30/10/2020 16:15:37 PORTRAIT D’ARTISTE 500 ESTAMPES 2020 SOMMAIRE AVANT-PROPOS .................................................................... 7 PRÉFACE ................................................................................ 9 ESTAMPES DES XVIe ET XVIIe SIÈCLES ............................. 15 ESTAMPES DU XVIIIe SIÈCLE ............................................. 61 ESTAMPES DU XIXe SIÈCLE ................................................ 105 ESTAMPES DU XXe SIÈCLE ................................................. 171 INDEX .................................................................................... 202 AVANT-PROPOS près avoir quitté la maison familiale du 12 de la rue de Seine, Paul Prouté s’instal- Alait au 74 de cette même rue le 15 janvier -

Daniel Cottier's Aesthetic of Beauty in Australia

Daniel Cottier’s Aesthetic of Beauty in Australia Andrew Montana Detail from Fig. 11. Lyon, Cottier & Co. The Seasons staircase window Glenyarrah mansion, Sydney. c.1876. “A range of performance beyond any modern artist”; so Ford Madox Brown’s appreciation of the work of his former pupil, the brilliant colourist, decorator and stained glass artist, Daniel Cottier (1837-91) was reported in the Glaswegian press. “Here tone and colour are suggestive of paradise itself,” he enthused about Cottier’s decorative enrichment of the interior of Queen’s Park United Presbyterian Church (1867-69), which Brown saw in Glasgow in 1883.1 Brown had befriended Cottier in the late 1850s at the Working Men’s College in Red Lion Square, London, where Cottier attended lectures by John Ruskin and was instructed in draw- ing by Brown, who had taken over from Dante Gabriel Rossetti.2 Through Brown, Cottier studied Pre-Raphaelite art and observed the formation of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co. in London in 1861.3 Following on from Morris’s example, Cottier made a successful career from his decorating businesses in London, New York, and Sydney, where he co-established Lyon, Cottier & Co. in 1873. He brought distinctive expressions of the British Aesthetic movement in painted and 1 “Gossip and Grumbles,” Evening Times (Glasgow), 9 Oct. 1893, p. 1. 2 Margaret H. Hobler: In Search of Daniel Cottier, Artistic Entrepreneur, 1838-1891. The City University of New York: M. A. Thesis (unpub.), Hunter College, 1987, pp. 10, 22. 3 Juliet Kinchin: “Cottier’s in Context: the Significance of Dowanhill Church.” Cottier’s in Context: Daniel Cottier, William Leiper and Dowanhill Church, Glasgow. -

The Impact of Medardo Rosso's Internationalism on His Legacy

Sharon Hecker Born on a train: the impact of Medardo Rosso’s internationalism on his legacy In 1977 and 2014, the Italian Ministry of Culture (Soprintendenza Archeologia, Belle Arti e Paesaggio) declared numerous sculptures by Medardo Rosso (1858–1928) to be of national cultural interest and therefore not exportable.1 This decree is based on the premise of Rosso’s ties to Italy, his country of birth and death, as well as on the Ministry’s belief in his relevance for Italian art, culture and history. However, Rosso’s national identity has never been secure. Today’s claims for his ‘belonging’ to Italy are complicated by his international career choices, including his emigration to Paris and naturalization as a French citizen, his declared identity as an internationalist, and his art, which defies (national) categorization.2 Italy’s legal and political notifica (literally meaning ‘notification’ or national ‘designation’), as it is termed, of Rosso’s works represents a revisionist effort to settle and claim his loyalties. Such attempts rewrite the narrative of art history, and by framing Rosso according to exclusively Italian criteria, limit the kinds of questions asked about his work. They also shed light on Italy’s complex mediations between laying claim to an emerging modernism and to a national art. This essay assesses the long-term effects of Rosso’s transnational travel upon his national reputation and legacy. I contend that Rosso, by his own design, presented himself as an outsider who did not belong to national schools and nationally defined movements of his time. This was a major factor that contributed to his modernity. -

Vincent Van Gogh the Starry Night

Richard Thomson Vincent van Gogh The Starry Night the museum of modern art, new york The Starry Night without doubt, vincent van gogh’s painting the starry night (fig. 1) is an iconic image of modern culture. One of the beacons of The Museum of Modern Art, every day it draws thousands of visitors who want to gaze at it, be instructed about it, or be photographed in front of it. The picture has a far-flung and flexible identity in our collective musée imaginaire, whether in material form decorating a tie or T-shirt, as a visual quotation in a book cover or caricature, or as a ubiquitously understood allusion to anguish in a sentimental popular song. Starry Night belongs in the front rank of the modern cultural vernacular. This is rather a surprising status to have been achieved by a painting that was executed with neither fanfare nor much explanation in Van Gogh’s own correspondence, that on reflection the artist found did not satisfy him, and that displeased his crucial supporter and primary critic, his brother Theo. Starry Night was painted in June 1889, at a period of great complexity in Vincent’s life. Living at the asylum of Saint-Rémy in the south of France, a Dutchman in Provence, he was cut off from his country, family, and fellow artists. His isolation was enhanced by his state of health, psychologically fragile and erratic. Yet for all these taxing disadvantages, Van Gogh was determined to fulfill himself as an artist, the road that he had taken in 1880. -

Copyright Statement

COPYRIGHT STATEMENT This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. i ii REX WHISTLER (1905 – 1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY by NIKKI FRATER A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY School of Humanities & Performing Arts Faculty of Arts and Humanities September 2014 iii Nikki Frater REX WHISTLER (1905-1944): PATRONAGE AND ARTISTIC IDENTITY Abstract This thesis explores the life and work of Rex Whistler, from his first commissions whilst at the Slade up until the time he enlisted for active service in World War Two. His death in that conflict meant that this was a career that lasted barely twenty years; however it comprised a large range of creative endeavours. Although all these facets of Whistler’s career are touched upon, the main focus is on his work in murals and the fields of advertising and commercial design. The thesis goes beyond the remit of a purely biographical stance and places Whistler’s career in context by looking at the contemporary art world in which he worked, and the private, commercial and public commissions he secured. In doing so, it aims to provide a more comprehensive account of Whistler’s achievement than has been afforded in any of the existing literature or biographies. This deeper examination of the artist’s practice has been made possible by considerable amounts of new factual information derived from the Whistler Archive and other archival sources. -

Impressionism: Masterworks on Paper

Impressionism: Masterworks on Paper Find below a list of all the resources on this site related to Impressionism: Masterworks on Paper, on view October 14, 2011 January 8, 2012, at the Milwaukee Art Museum. Information for Teachers Background Information Exhibition Walkthrough Technique & Vocabulary Nudity in Art and Your Students Planning Your Visit Classroom Activities Pre-Visit Activity: Playing on Paper Pre-Visit Activity: Parlez-vous Français? Pre-Visit Activity: A Field Trip to Impressionist Europe Post-Visit Activity: Making Marks Part II (see Gallery Activities for Part I) Post-Visit Activity: Répondez S'il Vous Plaît Gallery Activities Making Marks Part I (Eye Spy) Background Information Featuring over 120 works on paper pastels, watercolors, and drawings by some of the most famous artists in the history of Western European art, Impressionism: Masterworks on Paper is an exhibition with a game-changing thesis. Older students can dive into what is fresh in art history as a result of this new scholarship, while younger students can engage with works by Monet, Degas, Van Gogh, Cézanne, and others. Notably, these works on paper are rarely seen because they are extremely delicate and sensitive to light. Works on paper are generally shown for only three months at a time, after which they must go back into storage for at least three years. You probably already know the Impressionists and Post-Impressionists represented in this exhibition but did you know that these artists created art other than painting? Many of their most experimental and groundbreaking techniques and ideas were fleshed out on paper rather than on canvas. -

The London Old Masters Market and Modern British Painting (1900–14)

Chapter 4 (Inter)national Art: The London Old Masters Market and Modern British Painting (1900–14) Barbara Pezzini Introduction: Conflicting National Canons In his popular and successful essay Reflections on British Painting, an el- derly Roger Fry—who died in September 1934, the same year of this essay’s publication—criticised the art-historical use of a concept closely related to na- tionalism: patriotism.1 For Fry the critical appreciation of works of art should be detached from geographical allegiances and instead devoted ‘towards an ideal end’ that had ‘nothing to do with the boundaries between nations.’ Fry also minimised the historical importance of British art, declaring it ‘a minor school.’2 According to Fry, British artists failed to recognise a higher purpose in their art and thus produced works that merely satisfied their immediate con- temporaries instead of serving ‘posterity and mankind at large.’3 Their formal choices—which tended towards the linear and generally showed an absence of the plastic awareness and sculptural qualities of other European art, especially Italian—were also considered by Fry to be a serious limitation. Fry’s remarks concerning patriotism in art were directed against the aggressive political na- tionalism of the 1930s, but the ideas behind them had long been debated. They were, in fact, a development of earlier formalist ideas shared in part by other writers of the Bloomsbury set and popularised by Clive Bell’s 1914 discussion of ‘significant form.’4 For Fry, as for Bell, there was a positive lineage to be found in art, a stylistic continuum that passed from Giotto through Poussin to arrive to Cézanne. -

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) Had Only Seven Members but Influenced Many Other Artists

1 • Of course, their patrons, largely the middle-class themselves form different groups and each member of the PRB appealed to different types of buyers but together they created a stronger brand. In fact, they differed from a boy band as they created works that were bought independently. As well as their overall PRB brand each created an individual brand (sub-cognitive branding) that convinced the buyer they were making a wise investment. • Millais could be trusted as he was a born artist, an honest Englishman and made an ARA in 1853 and later RA (and President just before he died). • Hunt could be trusted as an investment as he was serious, had religious convictions and worked hard at everything he did. • Rossetti was a typical unreliable Romantic image of the artist so buying one of his paintings was a wise investment as you were buying the work of a ‘real artist’. 2 • The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) had only seven members but influenced many other artists. • Those most closely associated with the PRB were Ford Madox Brown (who was seven years older), Elizabeth Siddal (who died in 1862) and Walter Deverell (who died in 1854). • Edward Burne-Jones and William Morris were about five years younger. They met at Oxford and were influenced by Rossetti. I will discuss them more fully when I cover the Arts & Crafts Movement. • There were many other artists influenced by the PRB including, • John Brett, who was influenced by John Ruskin, • Arthur Hughes, a successful artist best known for April Love, • Henry Wallis, an artist who is best known for The Death of Chatterton (1856) and The Stonebreaker (1858), • William Dyce, who influenced the Pre-Raphaelites and whose Pegwell Bay is untypical but the most Pre-Raphaelite in style of his works. -

Japonisme in Britain - a Source of Inspiration: J

Japonisme in Britain - A Source of Inspiration: J. McN. Whistler, Mortimer Menpes, George Henry, E.A. Hornel and nineteenth century Japan. Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History of Art, University of Glasgow. By Ayako Ono vol. 1. © Ayako Ono 2001 ProQuest Number: 13818783 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818783 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 4 8 1 0 6 - 1346 GLASGOW UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 122%'Cop7 I Abstract Japan held a profound fascination for Western artists in the latter half of the nineteenth century. The influence of Japanese art is a phenomenon that is now called Japonisme , and it spread widely throughout Western art. It is quite hard to make a clear definition of Japonisme because of the breadth of the phenomenon, but it could be generally agreed that it is an attempt to understand and adapt the essential qualities of Japanese art. This thesis explores Japanese influences on British Art and will focus on four artists working in Britain: the American James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903), the Australian Mortimer Menpes (1855-1938), and two artists from the group known as the Glasgow Boys, George Henry (1858-1934) and Edward Atkinson Hornel (1864-1933). -

Charles Fairfax Murray Collection: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8833xp9 No online items Charles Fairfax Murray Collection: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Gayle M. Richardson, October 26, 2011. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2016 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Charles Fairfax Murray Collection: mssHM 76265-76327 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Charles Fairfax Murray Collection Dates (inclusive): 1866-1916 Collection Number: mssHM 76265-76327 Creator: Murray, Charles Fairfax, 1849-1919. Extent: 62 pieces. 1 box. Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This 62-piece collection chiefly contains correspondence to Pre-Raphaelite artist and art collector Charles Fairfax Murray (1849-1919), as well as a few manuscripts by Murray and seven unsigned pencil and ink sketches, some of which are by Murray. Language: English and Italian Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Charles Fairfax Murray Collection, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California.