America's National Gallery Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Paintings and Sculpture Given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr

e. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE THE COLLECTIONS OF THE NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART \YASHINGTON The National Gallery will open to the public on March 18, 1941. For the first time, the Mellon Collection, deeded to the Nation in 1937, and the Kress Collection, given in 1939, will be shown. Both collections are devoted exclusively to painting and sculpture. The Mellon Collection covers the principal European schools from about the year 1200 to the early XIX Century, and includes also a number of early American portraits. The Kress Collection exhibits only Italian painting and sculpture and illustrates the complete development of the Italian schools from the early XIII Century in Florence, Siena, and Rome to the last creative moment in Venice at the end of the XVIII Century. V.'hile these two great collections will occupy a large number of galleries, ample space has been left for future development. Mr. Joseph E. Videner has recently announced that the Videner Collection is destined for the National Gallery and it is expected that other gifts will soon be added to the National Collection. Even at the present time, the collections in scope and quality will make the National Gallery one of the richest treasure houses of art in the wor 1 d. The paintings and sculpture given to the Nation by Mr. Kress and Mr. Mellon have been acquired from some of -2- the most famous private collections abroad; the Dreyfus Collection in Paris, the Barberini Collection in Rome, the Benson Collection in London, the Giovanelli Collection in Venice, to mention only a few. -

National Mall Existing Conditions

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior National Mall and Memorial Parks Washington, D.C. Photographs of Existing Conditions on the National Mall Summer 2009 and Spring 2010 CONTENTS Views and Vistas ............................................................................................................................ 1 Views from the Washington Monument ................................................................................. 1 The Classic Vistas .................................................................................................................... 3 Views from Nearby Areas........................................................................................................8 North-South Views from the Center of the Mall ...................................................................... 9 Union Square............................................................................................................................... 13 The Mall ...................................................................................................................................... 17 Washington Monument and Grounds.......................................................................................... 22 World War II Memorial................................................................................................................. 28 Constitution Gardens................................................................................................................... 34 Vietnam Veterans Memorial........................................................................................................ -

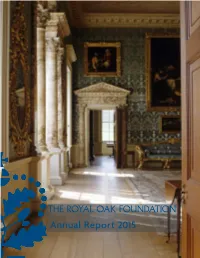

Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of Contents

THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION Annual Report 2015 ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Table of Contents Letter from the Chairman and the Executive Director 2 EXPERIENCE & LEARN Membership 3 Heritage Circle UK Study Day 4 Programs and Lectures 5 Scholarships 6 SUPPORT Grants to National Trust Properties 7-8 Financial Summary 9-10 2015 National Trust Appeal 11 2015 National Trust Appeal Donors 12-13 Royal Oak Foundation Annual Donors 14-16 Legacy Circle 17 Timeless Design Gala Benefit 18 Members 19-20 BOARD OF DIRECTORS & STAFF 22 Our Mission The Royal Oak Foundation inspires Americans to learn about, experience and support places of great historic and natural significance in the United Kingdom in partnership with the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. royal-oak.org ANNUAL REPORT 2015 2 THE ROYAL OAK FOUNDATION Americans in Alliance with the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland September 2016 Dear Royal Oak Community: On behalf of the Royal Oak Board of Directors and staff, we express our continued gratitude to you, our loyal community of members, donors and friends, who help sustain the Foundation’s mission to support the National Trust of England, Wales and Northern Ireland. Together, we preserve British history and landscapes and encourage experiences that teach and inspire. It is with pleasure that we present to you the 2015 Annual Report and share highlights from a very full and busy year. We marked our 42nd year as an American affiliate of the National Trust in 2015. Having embarked on a number of changes – from new office space and staff to new programmatic initiatives, we have stayed true to our mission to inspire Americans to learn about, experience, and support places of great historic and natural significance in the UK. -

5 the Da Vinci Code Dan Brown

The Da Vinci Code By: Dan Brown ISBN: 0767905342 See detail of this book on Amazon.com Book served by AMAZON NOIR (www.amazon-noir.com) project by: PAOLO CIRIO paolocirio.net UBERMORGEN.COM ubermorgen.com ALESSANDRO LUDOVICO neural.it Page 1 CONTENTS Preface to the Paperback Edition vii Introduction xi PART I THE GREAT WAVES OF AMERICAN WEALTH ONE The Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: From Privateersmen to Robber Barons TWO Serious Money: The Three Twentieth-Century Wealth Explosions THREE Millennial Plutographics: American Fortunes 3 47 and Misfortunes at the Turn of the Century zoART II THE ORIGINS, EVOLUTIONS, AND ENGINES OF WEALTH: Government, Global Leadership, and Technology FOUR The World Is Our Oyster: The Transformation of Leading World Economic Powers 171 FIVE Friends in High Places: Government, Political Influence, and Wealth 201 six Technology and the Uncertain Foundations of Anglo-American Wealth 249 0 ix Page 2 Page 3 CHAPTER ONE THE EIGHTEENTH AND NINETEENTH CENTURIES: FROM PRIVATEERSMEN TO ROBBER BARONS The people who own the country ought to govern it. John Jay, first chief justice of the United States, 1787 Many of our rich men have not been content with equal protection and equal benefits , but have besought us to make them richer by act of Congress. -Andrew Jackson, veto of Second Bank charter extension, 1832 Corruption dominates the ballot-box, the Legislatures, the Congress and touches even the ermine of the bench. The fruits of the toil of millions are boldly stolen to build up colossal fortunes for a few, unprecedented in the history of mankind; and the possessors of these, in turn, despise the Republic and endanger liberty. -

Martin Van Buren: the Greatest American President

SUBSCRIBE NOW AND RECEIVE CRISIS AND LEVIATHAN* FREE! “The Independent Review does not accept “The Independent Review is pronouncements of government officials nor the excellent.” conventional wisdom at face value.” —GARY BECKER, Noble Laureate —JOHN R. MACARTHUR, Publisher, Harper’s in Economic Sciences Subscribe to The Independent Review and receive a free book of your choice* such as the 25th Anniversary Edition of Crisis and Leviathan: Critical Episodes in the Growth of American Government, by Founding Editor Robert Higgs. This quarterly journal, guided by co-editors Christopher J. Coyne, and Michael C. Munger, and Robert M. Whaples offers leading-edge insights on today’s most critical issues in economics, healthcare, education, law, history, political science, philosophy, and sociology. Thought-provoking and educational, The Independent Review is blazing the way toward informed debate! Student? Educator? Journalist? Business or civic leader? Engaged citizen? This journal is for YOU! *Order today for more FREE book options Perfect for students or anyone on the go! The Independent Review is available on mobile devices or tablets: iOS devices, Amazon Kindle Fire, or Android through Magzter. INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE, 100 SWAN WAY, OAKLAND, CA 94621 • 800-927-8733 • [email protected] PROMO CODE IRA1703 Martin Van Buren The Greatest American President —————— ✦ —————— JEFFREY ROGERS HUMMEL resident Martin Van Buren does not usually receive high marks from histori- ans. Born of humble Dutch ancestry in December 1782 in the small, upstate PNew York village of Kinderhook, Van Buren gained admittance to the bar in 1803 without benefit of higher education. Building on a successful country legal practice, he became one of the Empire State’s most influential and prominent politi- cians while the state was surging ahead as the country’s wealthiest and most populous. -

Campaign and Transition Collection: 1928

HERBERT HOOVER PAPERS CAMPAIGN LITERATURE SERIES, 1925-1928 16 linear feet (31 manuscript boxes and 7 card boxes) Herbert Hoover Presidential Library 151 Campaign Literature – General 152-156 Campaign Literature by Title 157-162 Press Releases Arranged Chronologically 163-164 Campaign Literature by Publisher 165-180 Press Releases Arranged by Subject 181-188 National Who’s Who Poll Box Contents 151 Campaign Literature – General California Elephant Campaign Feature Service Campaign Series 1928 (numerical index) Cartoons (2 folders, includes Satterfield) Clipsheets Editorial Digest Editorials Form Letters Highlights on Hoover Booklets Massachusetts Elephant Political Advertisements Political Features – NY State Republican Editorial Committee Posters Editorial Committee Progressive Magazine 1928 Republic Bulletin Republican Feature Service Republican National Committee Press Division pamphlets by Arch Kirchoffer Series. Previously Marked Women's Page Service Unpublished 152 Campaign Literature – Alphabetical by Title Abstract of Address by Robert L. Owen (oversize, brittle) Achievements and Public Services of Herbert Hoover Address of Acceptance by Charles Curtis Address of Acceptance by Herbert Hoover Address of John H. Bartlett (Herbert Hoover and the American Home), Oct 2, 1928 Address of Charles D., Dawes, Oct 22, 1928 Address by Simeon D. Fess, Dec 6, 1927 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Boston, Massachusetts, Oct 15, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Elizabethton, Tennessee. Oct 6, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – New York, New York, Oct 22, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – Newark, New Jersey, Sep 17, 1928 Address of Mr. Herbert Hoover – St. Louis, Missouri, Nov 2, 1928 Address of W. M. Jardine, Oct. 4, 1928 Address of John L. McNabb, June 14, 1928 Address of U. -

World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art

National Gallery of Art: Research Resources Relating to World War II World War II-Related Exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art During the war years, the National Gallery of Art presented a series of exhibitions explicitly related to the war or presenting works of art for which the museum held custody during the hostilities. Descriptions of each of the exhibitions is available in the list of past exhibitions at the National Gallery of Art. Catalogs, brochures, press releases, news reports, and photographs also may be available for examination in the Gallery Archives for some of the exhibitions. The Great Fire of London, 1940 18 December 1941-28 January 1942 American Artists’ Record of War and Defense 7 February-8 March 1942 French Government Loan 2 March 1942-1945, periodically Soldiers of Production 17 March-15 April 1942 Three Triptychs by Contemporary Artists 8-15 April 1942 Paintings, Posters, Watercolors, and Prints, Showing the Activities of the American Red Cross 2-30 May 1942 Art Exhibition by Men of the Armed Forces 5 July-2 August 1942 War Posters 17 January-18 February 1943 Belgian Government Loan 7 February 1943-January 1946 War Art 20 June-1 August 1943 Nineteenth- and Twentieth-Century Drawings and Watercolors from French Museums and Private Collections 8 August-5 September 1943 (second showing) Art for Bonds 12 September-10 October 1943 1DWLRQDO*DOOHU\RI$UW:DVKLQJWRQ'&*DOOHU\$UFKLYHV ::,,5HODWHG([KLELWLRQVDW1*$ Marine Watercolors and Drawings 12 September-10 October 1943 Paintings of Naval Aviation by American Artists -

Presidents Worksheet 43 Secretaries of State (#1-24)

PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 43 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#1-24) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 9,10,13 Daniel Webster 1 George Washington 2 John Adams 14 William Marcy 3 Thomas Jefferson 18 Hamilton Fish 4 James Madison 5 James Monroe 5 John Quincy Adams 6 John Quincy Adams 12,13 John Clayton 7 Andrew Jackson 8 Martin Van Buren 7 Martin Van Buren 9 William Henry Harrison 21 Frederick Frelinghuysen 10 John Tyler 11 James Polk 6 Henry Clay (pictured) 12 Zachary Taylor 15 Lewis Cass 13 Millard Fillmore 14 Franklin Pierce 1 John Jay 15 James Buchanan 19 William Evarts 16 Abraham Lincoln 17 Andrew Johnson 7, 8 John Forsyth 18 Ulysses S. Grant 11 James Buchanan 19 Rutherford B. Hayes 20 James Garfield 3 James Madison 21 Chester Arthur 22/24 Grover Cleveland 20,21,23James Blaine 23 Benjamin Harrison 10 John Calhoun 18 Elihu Washburne 1 Thomas Jefferson 22/24 Thomas Bayard 4 James Monroe 23 John Foster 2 John Marshall 16,17 William Seward PRESIDENTS WORKSHEET 44 NAME SOLUTION KEY SECRETARIES OF STATE (#25-43) Write the number of each president who matches each Secretary of State on the left. Some entries in each column will match more than one in the other column. Each president will be matched at least once. 32 Cordell Hull 25 William McKinley 28 William Jennings Bryan 26 Theodore Roosevelt 40 Alexander Haig 27 William Howard Taft 30 Frank Kellogg 28 Woodrow Wilson 29 Warren Harding 34 John Foster Dulles 30 Calvin Coolidge 42 Madeleine Albright 31 Herbert Hoover 25 John Sherman 32 Franklin D. -

GSP NEWSLETTER Finding Your Pennsylvania Ancestors

September 2020 Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Newsletter GSP NEWSLETTER Finding Your Pennsylvania Ancestors Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania Newsletter In this issue MESSAGE FROM GSP’S PRESIDENT • Library update.…..…………2 Working Hard Behind the Scenes • Did You Know? …………….2 The Genealogical Society of Pennsylvania (GSP) is currently • First Families Corner………3 working on the Sharla Solt Kistler Collection, which was • County Spotlight: donated to GSP by Mrs. Sharla Solt Kistler. Mrs. Kistler was an Columbia……………………4 avid genealogist with a vast collection of books and records reflecting her years of research. She donated her collection to • GSP members’ Civil War GSP so that her work and passion could be shared. ancestors…………….….…..5 • Q&A: DNA ..…………………9 The collection represents Mrs. Kistler’s many years of research • Tell Us About It………….…10 on her ancestors, largely in the Lehigh Valley area of Eastern Pennsylvania. It includes her personal research and • PGM Excerpt: Identifying correspondence. Available are numerous transcriptions of 19th-century photographs church and cemetery records from Berks, Schuylkill, Lehigh, ………………………………11 and Northampton counties, as well as numerous books. Pennsylvanians of German ancestry are well represented in Update about GSP this collection. Volunteers are cataloging the collection and hoping to create Although our office is not yet finding aids for researchers to use both on site and online. open to visitors, staff is here on Monday, Tuesday, and Even though GSP’s library is still closed to visitors because of Thursday from 10 am to 3 pm the pandemic, volunteers are hard at work on this, as well as and can respond to your other projects. -

Patriots, Pioneers and Presidents Trail to Discover His Family to America in 1819, Settling in Cincinnati

25 PLACES TO VISIT TO PLACES 25 MAP TRAIL POCKET including James Logan plaque, High Street, Lurgan FROM ULSTER ULSTER-SCOTS AND THE DECLARATION THE WAR OF 1 TO AMERICA 2 COLONIAL AMERICA 3 OF INDEPENDENCE 4 INDEPENDENCE ULSTER-SCOTS, The Ulster-Scots have always been a transatlantic people. Our first attempted Ulster-Scots played key roles in the settlement, The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish contribution to the Patriot cause in the events The Ulster-Scots/Scotch-Irish played important roles in the military aspects of emigration was in 1636 when Eagle Wing sailed from Groomsport for New England administration and defence of Colonial America. leading up to and including the American War of Independence was immense. the War of Independence. General Richard Montgomery was the descendant of SCOTCH-IRISH but was forced back by bad weather. It was 1718 when over 100 families from the Probably born in County Donegal, Rev. Charles Cummings (1732–1812), a a Scottish cleric who moved to County Donegal in the 1600s. At a later stage the AND SCOTS-IRISH Bann and Foyle river valleys successfully reached New England in what can be James Logan (1674-1751) of Lurgan, County Armagh, worked closely with the Penn family in the Presbyterian minister in south-western Virginia, is believed to have drafted the family acquired an estate at Convoy in this county. Montgomery fought for the regarded as the first organised migration to bring families to the New World. development of Pennsylvania, encouraging many Ulster families, whom he believed well suited to frontier Fincastle Resolutions of January 1775, which have been described as the first Revolutionaries and was killed at the Battle of Quebec in 1775. -

The London Old Masters Market and Modern British Painting (1900–14)

Chapter 4 (Inter)national Art: The London Old Masters Market and Modern British Painting (1900–14) Barbara Pezzini Introduction: Conflicting National Canons In his popular and successful essay Reflections on British Painting, an el- derly Roger Fry—who died in September 1934, the same year of this essay’s publication—criticised the art-historical use of a concept closely related to na- tionalism: patriotism.1 For Fry the critical appreciation of works of art should be detached from geographical allegiances and instead devoted ‘towards an ideal end’ that had ‘nothing to do with the boundaries between nations.’ Fry also minimised the historical importance of British art, declaring it ‘a minor school.’2 According to Fry, British artists failed to recognise a higher purpose in their art and thus produced works that merely satisfied their immediate con- temporaries instead of serving ‘posterity and mankind at large.’3 Their formal choices—which tended towards the linear and generally showed an absence of the plastic awareness and sculptural qualities of other European art, especially Italian—were also considered by Fry to be a serious limitation. Fry’s remarks concerning patriotism in art were directed against the aggressive political na- tionalism of the 1930s, but the ideas behind them had long been debated. They were, in fact, a development of earlier formalist ideas shared in part by other writers of the Bloomsbury set and popularised by Clive Bell’s 1914 discussion of ‘significant form.’4 For Fry, as for Bell, there was a positive lineage to be found in art, a stylistic continuum that passed from Giotto through Poussin to arrive to Cézanne. -

Annual Report 1995

19 9 5 ANNUAL REPORT 1995 Annual Report Copyright © 1996, Board of Trustees, Photographic credits: Details illustrated at section openings: National Gallery of Art. All rights p. 16: photo courtesy of PaceWildenstein p. 5: Alexander Archipenko, Woman Combing Her reserved. Works of art in the National Gallery of Art's collec- Hair, 1915, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, 1971.66.10 tions have been photographed by the department p. 7: Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo, Punchinello's This publication was produced by the of imaging and visual services. Other photographs Farewell to Venice, 1797/1804, Gift of Robert H. and Editors Office, National Gallery of Art, are by: Robert Shelley (pp. 12, 26, 27, 34, 37), Clarice Smith, 1979.76.4 Editor-in-chief, Frances P. Smyth Philip Charles (p. 30), Andrew Krieger (pp. 33, 59, p. 9: Jacques-Louis David, Napoleon in His Study, Editors, Tarn L. Curry, Julie Warnement 107), and William D. Wilson (p. 64). 1812, Samuel H. Kress Collection, 1961.9.15 Editorial assistance, Mariah Seagle Cover: Paul Cezanne, Boy in a Red Waistcoat (detail), p. 13: Giovanni Paolo Pannini, The Interior of the 1888-1890, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon Pantheon, c. 1740, Samuel H. Kress Collection, Designed by Susan Lehmann, in Honor of the 50th Anniversary of the National 1939.1.24 Washington, DC Gallery of Art, 1995.47.5 p. 53: Jacob Jordaens, Design for a Wall Decoration (recto), 1640-1645, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund, Printed by Schneidereith & Sons, Title page: Jean Dubuffet, Le temps presse (Time Is 1875.13.1.a Baltimore, Maryland Running Out), 1950, The Stephen Hahn Family p.