Rembrandt Van Rijn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gary Schwartz

Gary Schwartz A Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings as a Test Case for Connoisseurship Seldom has an exercise in connoisseurship had more going for it than the world-famous Rembrandt Research Project, the RRP. This group of connoisseurs set out in 1968 to establish a corpus of Rembrandt paintings in which doubt concer- ning attributions to the master was to be reduced to a minimum. In the present enquiry, I examine the main lessons that can be learned about connoisseurship in general from the first three volumes of the project. My remarks are limited to two central issues: the methodology of the RRP and its concept of authorship. Concerning methodology,I arrive at the conclusion that the persistent appli- cation of classical connoisseurship by the RRP, attended by a look at scientific examination techniques, shows that connoisseurship, while opening our eyes to some features of a work of art, closes them to others, at the risk of generating false impressions and incorrect judgments.As for the concept of authorship, I will show that the early RRP entertained an anachronistic and fatally puristic notion of what constitutes authorship in a Dutch painting of the seventeenth century,which skewed nearly all of its attributions. These negative judgments could lead one to blame the RRP for doing an inferior job. But they can also be read in another way. If the members of the RRP were no worse than other connoisseurs, then the failure of their enterprise shows that connoisseurship was unable to deliver the advertised goods. I subscribe to the latter conviction. This paper therefore ends with a proposal for the enrichment of Rembrandt studies after the age of connoisseurship. -

Rembrandt: a Milestone of Portraiture

Artistic Narration: A Peer Reviewed Journal of Visual & Performing Art ISSN (P): 0976-7444 (e): 2395-7247 Vol. VIII. 2016 IMPACT Factor - 3.9651 Rembrandt: a Milestone of Portraiture Syed Ali Jafar Assistant Professor Dept. of Painting, D.S. College, Aligarh. Email: [email protected] Abstract When we talk about portraiture, the name of Dutch painter Rembrandt comes suddenly in our mind who was born in 1607 and studied art in the studio of a well known portrait painter Pieter Lastman in Amsterdam. Soon after learning all the basics of art, young Rembrandt established himself as a portrait painter along with a reputation as an etcher (print maker). As a result, young and energetic Rembrandt established his own studio and began to apprentice budding artist almost his own age. In 1632, Rembrandt married to Saskia van Ulyenburg, a cousin of a well known art dealer who was not in favour of this love marriage. Anyhow after the marriage, Rembrandt was so happy but destiny has written otherwise, his beloved wife Saskia was died just after giving birth to the son Titus. Anyhow same year dejected Rembrandt painted his famous painting „Night Watch‟ which pull down the reputation of the painter because Rembrandt painted it in his favourite dramatic spot light manner which was discarded by the officers who had commissioned the painting. Despite having brilliant qualities of drama, lighting scene and movement, Rembrandt was stopped to obtain the commission works. So he stared to paint nature to console himself. At the same time, Hendrickje Stoffels, a humble woman who cared much to child Titus, married Rembrandt wise fully and devoted her to reduce the tide of Rembrandt‟s misfortune. -

Rembrandt Self Portraits

Rembrandt Self Portraits Born to a family of millers in Leiden, Rembrandt left university at 14 to pursue a career as an artist. The decision turned out to be a good one since after serving his apprenticeship in Amsterdam he was singled out by Constantijn Huygens, the most influential patron in Holland. In 1634 he married Saskia van Uylenburgh. In 1649, following Saskia's death from tuberculosis, Hendrickje Stoffels entered Rembrandt's household and six years later they had a son. Rembrandt's success in his early years was as a portrait painter to the rich denizens of Amsterdam at a time when the city was being transformed from a small nondescript port into the The Night Watch 1642 economic capital of the world. His Rembrandt painted the large painting The Militia Company of Captain Frans Banning Cocq historical and religious paintings also between 1640 and 1642. This picture was called De Nachtwacht by the Dutch and The gave him wide acclaim. Night Watch by Sir Joshua Reynolds because by the 18th century the picture was so dimmed and defaced that it was almost indistinguishable, and it looked quite like a night scene. After it Despite being known as a portrait painter was cleaned, it was discovered to represent broad day—a party of musketeers stepping from a Rembrandt used his talent to push the gloomy courtyard into the blinding sunlight. boundaries of painting. This direction made him unpopular in the later years of The piece was commissioned for the new hall of the Kloveniersdoelen, the musketeer branch of his career as he shifted from being the the civic militia. -

The Seven Deadly SINS

The Seven Deadly SINS BERNARD QUARITCH LTD Index to the Sins Lust Items 1-14 Greed and Gluttony Items 15-23 Sloth Items 24-31 Wrath Items 32-40 Pride and Envy Items 41-51 All Seven Sins Item 52 See final page for payment details. I LUST THE STATISTICS OF DEBAUCHERY 1) [BARNAUD, Nicolas]. Le Cabinet du Roy de France, dans lequel il y a trois perles precieuses d’inestimable valeur: par le moyen desquelles sa Majesté s’en va le premier monarque du monde, & ses sujets du tout soulagez. [No place or printer], 1581. 8vo, pp. [xvi], 647, [11], [2, blank]; lightly browned or spotted in places, the final 6 leaves with small wormholes at inner margins; a very good copy in contemporary vellum with yapp edges; from the library of the Princes of Liechtenstein, with armorial bookplate on front paste- down. £2200 First edition, first issue, of this harsh criticism of the debauched church and rotten nobility and the resulting bad finances of France, anonymously published by a well-travelled Protestant physician, and writer on alchemy who was to become an associate of the reformer Fausto Paolo Sozzini, better known as Socinus, the founder of the reformist school influential in Poland. Barnaud was accused of atheism and excommunicated in 1604. He is one of the real historical figures, on which the Doctor Faustus legend is based. This ‘violent pamphlet against the clergy (translated from Dictionnaire de biographie française) is divided into three books, symbolized by pearls, as mentioned in the title. In the first book Barnaud gives an account and precise numbers of sodomites, illegitimate children, prostitutes etc. -

National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award

FOCUS Dr. Lawrence Buck, Michael G. O'Neill and Dr. Eric Brucker National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award Michael G. 0 ' eill , chairman of Be creati ve. Be sure that yo u are U ni ve rsity and juris doctorate from Preferred Real Estate Inves tments passionate about your wo rk, and Temple U nive rsity School of Law. (PREI), Inc., received the most impo rtantly, be yo urself. " Facul ty awards presen ted at the ban Distingui hed Perfo rmance in The PhiladeltJhia Business J ournal quet included the Di stinguished Manageme nt wa rd at the School o f ranked 0 ' eill' company the sec Graduate Teaching Award to Kenn Business Administrati o n's annual o nd largest commercial real estate Tacchino, pro fessor of taxatio n; th e scholarship banque t. This award is William Zahka Di sLin guished developer in the Philadelphia me t give n each year to individuals who Professor Award to Pe ter Oe hl ers, ropolitan area. Foll owing PREI's have made a significant contribu senio r lecturer of accounting; the success with the redevelopme nt of ti on to the wo rld of busine s. Distinguished Adjunct Teaching the Consho hocke n rive rfro nt, the Awa rd to Lawrence Colfe r, acUunct In his speech at the banque t, Mr. company has embarked o n a plan to pro fessor of ma nageme nt; and, the O 'Neill advised Widener business revitali ze the wate rfront distri ct of J o hn C. Sevi er wa rd for Dedicati o n students in attendan ce to "make Chester with a property call ed the and Service to the School of your greatnes in solving all the Wharf at Ri ve rtown. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Media Contact: Kim Hugo, (860) 838-4082 [email protected] Image file to accompany publicity of this announcement will be available for download at http://press.thewadsworth.org. Email to request login credentials. Major Rembrandt Portrait Painting on Loan to the Wadsworth from the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Hartford, Conn. (January 21, 2020)—Rembrandt’s Titus in a Monk’s Habit (1660) is coming to Hartford, Connecticut. On loan from the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, the painting will be on view at the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art from February 1 through April 30, 2020. Rembrandt van Rijn (1606–1669), recognized as one of the most important artists of his time and considered by many to be one of the greatest painters in European history, painted his teenage son in the guise of a monk at a crucial moment in his late career when he was revamping his business as a painter and recovering from bankruptcy. It has been fifty-three years since this painting has been on view in the United States making this a rare opportunity for visitors to experience a late portrait by the Dutch master among the collection of Baroque art at the Wadsworth renowned for its standout paintings by Rembrandt’s southern European contemporaries, Zurbarán, Oratio Gentileschi, and Caravaggio. While this painting has been infrequently seen in America, it exemplifies the dramatic use of light and dark to express human emotion for which Rembrandt’s late works are especially prized. “Titus in a Monk’s Habit is an important painting. It opens questions about the artist’s career, his use of traditional subjects, and the bold technique that has won him enduring fame,” says Oliver Tostmann, Susan Morse Hilles Curator of European Art at the Wadsworth. -

Rembrandt Van Rijn Dutch / Holandés, 1606–1669

Dutch Artist (Artista holandés) Active Amsterdam / activo en Ámsterdam, 1600–1700 Amsterdam Harbor as Seen from the IJ, ca. 1620, Engraving on laid paper Amsterdam was the economic center of the Dutch Republic, which had declared independence from Spain in 1581. Originally a saltwater inlet, the IJ forms Amsterdam’s main waterfront with the Amstel River. In the seventeenth century, this harbor became the hub of a worldwide trading network. El puerto de Ámsterdam visto desde el IJ, ca. 1620, Grabado sobre papel verjurado Ámsterdam era el centro económico de la República holandesa, que había declarado su independencia de España en 1581. El IJ, que fue originalmente una bahía de agua salada, conforma la zona costera principal de Ámsterdam junto con el río Amstel. En el siglo XVII, este puerto se convirtió en el núcleo de una red comercial de carácter mundial. Gift of George C. Kenney II and Olga Kitsakos-Kenney, 1998.129 Jan van Noordt (after Pieter Lastman, 1583–1633) Dutch / Holandés, 1623/24–1676 Judah and Tamar, 17th century, Etching on laid paper This etching made in Amsterdam reproduces a painting by Rembrandt’s teacher, Pieter Lastman, who imparted his close knowledge of Italian painting, especially that of Caravaggio, to his star pupil. As told in Genesis 38, the twice-widowed Tamar disguises herself to seduce Judah, her unsuspecting father-in-law, whose faithless sons had not fulfilled their marital duties. Tamar conceived twins by Judah, descendants of whom included King David. Judá y Tamar, Siglo 17, Aguafuerte sobre papel acanalado Esta aguafuerte creada en Ámsterdam reproduce una pintura del maestro de Rembrandt, Pieter Lastman, quien impartió su vasto conocimiento de la pintura italiana, en especial la de Caravaggio, a su discípulo estrella. -

My Favourite Painting Monty Don a Woman Bathing in a Streamby

Source: Country Life {Main} Edition: Country: UK Date: Wednesday 16, May 2018 Page: 88 Area: 559 sq. cm Circulation: ABC 41314 Weekly Ad data: page rate £3,702.00, scc rate £36.00 Phone: 020 7261 5000 Keyword: Paradise Gardens My favourite painting Monty Don A Woman Bathing in a Stream by Rembrandt Monty Don is a writer, gardener and television presenter. His new book Paradise Gardens is out now, published by Two Roads i My grandfather took me to an art gallery every school holidays and, as my education progressed, we slowly worked our way through the London collections. Rembrandt, he told me, was the greatest artist who had ever lived. I nodded, but was uncertain on what to look for that would confirm that judgement. Then I saw this painting and instantly knew. The subject-almost certainly Rembrandt's common-law wife, Hendrickje Stoffels— is not especially beautiful nor has a body or demeanour that might command especial attention. But, as she lifts the hem of her shift to wade in the water, she is made transcendent by Rembrandt's genius. In this, the simplest of moments by an ordinary person in a painting that is hardly more than a sketch, Rembrandt has captured human love at its most 1 intimate and tender. And there is no A Woman Bathing in a Stream, 1654, by Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-69), 24 /4in 1 more worthy subject than that ? by 18 /2in, National Gallery, London John McEwen comments on^4 Woman Bathing in a Stream Geertje Dircx, Titus's nursemaid, became her church. -

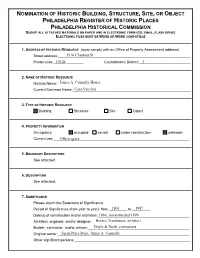

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

Widener University Not to Discriminate on the Basis of Sex

Accredited by the Middle States Associati on of Colleges and Schools. It is the policy of Widener University not to discriminate on the basis of sex. handicap, race, age, color, religion, or national or ethnic origin in its educational programs, admissions policies, employment policies, financial aid, or other school-administered programs. This policy is enforced by federa l law under Title IX oft he Educational Amendments of 1972. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of /964, and Section 504 of the Relwbilitation Act of 1973 . Whi le correct at press time, all statements in thi s publication are subject to change without notice. Upon action of the governing body, facilities may be enlarged or otherwi se altered, courses added or deleted, and the curricula modified or expanded. Bulletin of Widener University Ser ies 1.22 • Number 6 • September 1983 (USPS #074940) Published six times a year by Widener University, once each in June. Jul y, August, and three times in September. Second class postage paid at Chester, PA 19013 . POSTMASTER: Send Fonn 3579 to: Bulletin of Widener Uni versit y, Widener Universi ty, Chester. PA 19013. ) J Bulletin of { Widener University I I 't I 1983-1984 FOR INFORMATION Widener University, Chester, PA 19013 UNIVERSITY POLICY Mr. Robert J. Bruce, President ACADEMIC POLICY Dr. Clifford T. Stewart, Provost Mr. Joseph A. Arbuckle, Assistant Provost fo r the Pennsylvania Campus Dr. Lawrence P. Buck, Dean, College of Art and Sciences Dr. Thoma G . McWill iams, Jr. , Dean, School of Engineering Dr. John T. Meli , Dean, School of Management Dr. Janette L. -

The Circumcision 1661 Oil on Canvas Overall: 56.5 X 75 Cm (22 1/4 X 29 1/2 In.) Framed: 81.3 X 99 X 8.2 Cm (32 X 39 X 3 1/4 In.) Inscription: Lower Right: Rembrandt

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Rembrandt van Rijn Dutch, 1606 - 1669 The Circumcision 1661 oil on canvas overall: 56.5 x 75 cm (22 1/4 x 29 1/2 in.) framed: 81.3 x 99 x 8.2 cm (32 x 39 x 3 1/4 in.) Inscription: lower right: Rembrandt. f. 1661 Widener Collection 1942.9.60 ENTRY The only mention of the circumcision of Christ occurs in the Gospel of Luke, 2:15–22: “the shepherds said one to another, Let us now go even unto Bethlehem.... And they came with haste, and found Mary and Joseph, and the babe lying in a manger.... And when eight days were accomplished for the circumcising of the child, his name was called Jesus.” This cursory reference to this most significant event in the early childhood of Christ allowed artists throughout history a wide latitude in the way they represented the circumcision. [1] The predominant Dutch pictorial tradition was to depict the scene as though it occurred within the temple, as, for example, in Hendrick Goltzius (Dutch, 1558 - 1617)’ influential engraving of the Circumcision of Christ, 1594 [fig. 1]. [2] In the Goltzius print, the mohel circumcises the Christ child, held by the high priest, as Mary and Joseph stand reverently to the side. Rembrandt largely followed this tradition in his two early etchings of the subject and in his 1646 painting of the Circumcision for Prince Frederik Hendrik (now lost). [3] The Circumcision 1 © National Gallery of Art, Washington National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century The iconographic tradition of the circumcision occurring in the temple, which was almost certainly apocryphal, developed in the twelfth century to allow for a typological comparison between the Jewish rite of circumcision and the Christian rite of cleansing, or baptism.