View Nomination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rembrandt Van Rijn

Rembrandt van Rijn 1606-1669 REMBRANDT HARMENSZ. VAN RIJN, born 15 July er (1608-1651), Govaert Flinck (1615-1660), and 1606 in Leiden, was the son of a miller, Harmen Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), worked during these Gerritsz. van Rijn (1568-1630), and his wife years at Van Uylenburgh's studio under Rem Neeltgen van Zuytbrouck (1568-1640). The brandt's guidance. youngest son of at least ten children, Rembrandt In 1633 Rembrandt became engaged to Van was not expected to carry on his father's business. Uylenburgh's niece Saskia (1612-1642), daughter Since the family was prosperous enough, they sent of a wealthy and prominent Frisian family. They him to the Leiden Latin School, where he remained married the following year. In 1639, at the height of for seven years. In 1620 he enrolled briefly at the his success, Rembrandt purchased a large house on University of Leiden, perhaps to study theology. the Sint-Anthonisbreestraat in Amsterdam for a Orlers, Rembrandt's first biographer, related that considerable amount of money. To acquire the because "by nature he was moved toward the art of house, however, he had to borrow heavily, creating a painting and drawing," he left the university to study debt that would eventually figure in his financial the fundamentals of painting with the Leiden artist problems of the mid-1650s. Rembrandt and Saskia Jacob Isaacsz. van Swanenburgh (1571 -1638). After had four children, but only Titus, born in 1641, three years with this master, Rembrandt left in 1624 survived infancy. After a long illness Saskia died in for Amsterdam, where he studied for six months 1642, the very year Rembrandt painted The Night under Pieter Lastman (1583-1633), the most impor Watch (Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam). -

Wyncote, Pennsylvania: the History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 1985 Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Doreen L. Foust University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Foust, Doreen L., "Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb" (1985). Theses (Historic Preservation). 239. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb. (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/239 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and Preservation of a Victorian Philadelphia Suburb Disciplines Historic Preservation and Conservation Comments Copyright note: Penn School of Design permits distribution and display of this student work by University of Pennsylvania Libraries. Suggested Citation: Foust, Doreen L. (1985). Wyncote, Pennsylvania: The History, Development, Architecture and -

National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award

FOCUS Dr. Lawrence Buck, Michael G. O'Neill and Dr. Eric Brucker National Office Developer Receives Distinguished Performance Award Michael G. 0 ' eill , chairman of Be creati ve. Be sure that yo u are U ni ve rsity and juris doctorate from Preferred Real Estate Inves tments passionate about your wo rk, and Temple U nive rsity School of Law. (PREI), Inc., received the most impo rtantly, be yo urself. " Facul ty awards presen ted at the ban Distingui hed Perfo rmance in The PhiladeltJhia Business J ournal quet included the Di stinguished Manageme nt wa rd at the School o f ranked 0 ' eill' company the sec Graduate Teaching Award to Kenn Business Administrati o n's annual o nd largest commercial real estate Tacchino, pro fessor of taxatio n; th e scholarship banque t. This award is William Zahka Di sLin guished developer in the Philadelphia me t give n each year to individuals who Professor Award to Pe ter Oe hl ers, ropolitan area. Foll owing PREI's have made a significant contribu senio r lecturer of accounting; the success with the redevelopme nt of ti on to the wo rld of busine s. Distinguished Adjunct Teaching the Consho hocke n rive rfro nt, the Awa rd to Lawrence Colfe r, acUunct In his speech at the banque t, Mr. company has embarked o n a plan to pro fessor of ma nageme nt; and, the O 'Neill advised Widener business revitali ze the wate rfront distri ct of J o hn C. Sevi er wa rd for Dedicati o n students in attendan ce to "make Chester with a property call ed the and Service to the School of your greatnes in solving all the Wharf at Ri ve rtown. -

TORRIVENT Has Amazing Versatility for ALL HEATING

TORRIVENT has amaz ing versatility FOR ALL HEATING AND VENTILATING NEEDS H ere's today's most adaptable large CHECK THESE TORRIVENT FEATURES : capacity universal heating and ventilating e QUIETER OPERATION -New, high-efficiency TRANE unit-the TRANE TORRIVENT! This Fans have low outlet velocities for whisper-quiet versatile unit is especially designed to pro operation. e MORE VERSATILE- Torrivent units heat, filter, clean vide maximum heat transfer for large air any combination of recirculated and outside air to capacities in all types of buildings . meet heating-ventilating requirements for buildings of every size and type. May be installed with or commercial, institutional and industrial. without duct work on floor, wall or ceiling. TORRIVENTcan be used for free delivery e MORE FLEXIBLE-Complete range of coil types and or for discharge into ductwork. Many sizes to meet every need. casings are available, with damper ar e WIDER RANGE- Nine sizes- 1, 2 or 3 fan models. rangements and discharge provisions e LONGER LIFE-Casing is of uniframe construction. Fan shafts are solid (not hollow), large diameter for to suit any job. minimum vibration. Fan bearings are mounted ex Ask your TRANE ternally for easy maintenance. Representat ive e LOWER COST-Greater coil and fan efficiency and multiple coil choice permit selection of equipment about TORRI that meets requirements exactly. No wasted VENT .. or write capacity! today for the de Branch Offices in all principal Cities tailed Technical Bulletin. Manufacturers of Equipment for Air Conditioning, Heating, TR-5723-R Ventilating. COMPANY OF CANADA LIMITED, TORONTO 14 OCTOBER, 1959 Seria l No 410, Vol. -

Take a Walk Through Time with Fairmont Hotels & Resorts

FAIRMONT HOTELS & RESORTS TAKE A WALK THROUGH TIME WITH FAIRMONT HOTELS & RESORTS For more than a century, our hotels have been at the heart of it all, serving as places of occasion for their communities. The exhilarating events, memorable meetings, and defining moments that have taken place within our hallowed halls are fascinating and countless. A look at some of the more notable ones: 1885 Bermuda's The Fairmont Hamilton Princess opens its doors, making it the oldest hotel in the Fairmont collection. 1888 Canada's first grand railway hotel, The Fairmont Banff Springs opens, bringing to life the vision of General Manager and soon-to-be President of Canadian Pacific Railway, Sir Cornelius Van Horne. It’s not all joy though, as Van Horne is furious to discover initial hotel plans give the kitchen the magnificent views of the Bow Valley. A rotunda is soon built to give the view back to the guests. 1889 Britain's first luxury hotel, The Savoy, opens and pioneers a number of “firsts” for hotels, including “ascending rooms” (electric lifts), 24-hour room service through a “speaking tube” connected to the restaurant, and its own laundry service and postal address. 1890's Silver baron James Graham Fair purchases the land where Fairmont's namesake San Francisco hotel now resides, hoping to build a family estate. His daughters begin planning on “The Fairmont” as a posthumous monument. “Fairmont” combines the name of the hotel’s founding family with its exclusive location atop Nob Hill. 1890 Society hostess Lady de Grey gathers a group of female contemporaries to dine at London’s The Savoy, a strike for equality, making it socially acceptable for women to gather for meals in public without their husbands, and inspiring generations of ladies-who-lunch. -

9101 Germantown Avenue St. Michael's Hall, Located on a Large

St. Michael’s Hall, aka Alfred C. Harrison Country Estate – 9101 Germantown Avenue St. Michael’s Hall, located on a large wooded lot at the corner of Germantown and Sunset Avenues in Chestnut Hill, served as a summertime country retreat for its first sixty years. Between the time the house was built in the late 1850s, and 1924, St. Michael’s Hall was owned by three wealthy industrialists—William Henry Trotter (ownership 1855-1868), Henry Latimer Norris (ownership 1868-1884), and Alfred Craven Harrison (ownership 1884-1924). The Convent of the Sisters of St. Joseph of Chestnut Hill purchased the site in 1927, using it first as a school and then as a residence hall for nuns. The nuns vacated the property in September 2020, although it is still currently maintained by the Sisters of St. Joseph. 9101 Germantown Avenue, ca. 1903-1910 Courtesy of Chestnut Hill Conservancy Site Details • Built between 1855 and 1857, the house was originally rectangular in shape, measuring 40 by 43 feet. No architect has been attributed to the original building. • A small wing in the Gothic Revival style was added to the southeast elevation at an unknown date. • A small bay was added to the southwest (Germantown Avenue) elevation in 1896. • In 1899 two large wings in the Italianate style were added to the southeast and northeast elevations by architects Cope & Stewardson. • The 27,500 sq.ft. building sits on a lot of approximately 4 acres zoned RSD3, with 420’ of frontage bounded by Green Tree, Hampton, E Sunset, and Germantown. • The property is considered a “Significant” property in the Chestnut Hill National Register Historic District, but not listed on the Philadelphia Register of Historic Places. -

La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Magazine University Publications Summer 1974 La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle Magazine Summer 1974" (1974). La Salle Magazine. 140. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine/140 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Magazine by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 1974 JONES and CUNNINGHAM of The Newsroom A QUARTERLY LA SALLE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Volume 18 Summer, 1974 Number 3 Robert S. Lyons, Jr., ’61, Editor Joseph P. Batory, ’64, Associate Editor James J. McDonald, ’58, Alumni News ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OFFICERS John J. McNally, ’64, President Joseph M. Gindhart, Esq., ’58, Executive Vice President Julius E. Fioravanti, Esq., ’53, Vice President Ronald C. Giletti, ’62, Secretary Catherine A. Callahan, ’71, Treasurer La Salle M agazine is published quarterly by La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141, for the alumni, students, faculty and friends of the college. Editorial and business offices located at the News Bureau, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Second class postage paid at Philadelphia, Penna. Changes of address should be sent at least 30 days prior to publication of the issue with which it is to take effect, to the Alumni Office, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Member of the American Alumni Council and Ameri can College Public Relations Association. -

Widener University Not to Discriminate on the Basis of Sex

Accredited by the Middle States Associati on of Colleges and Schools. It is the policy of Widener University not to discriminate on the basis of sex. handicap, race, age, color, religion, or national or ethnic origin in its educational programs, admissions policies, employment policies, financial aid, or other school-administered programs. This policy is enforced by federa l law under Title IX oft he Educational Amendments of 1972. Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of /964, and Section 504 of the Relwbilitation Act of 1973 . Whi le correct at press time, all statements in thi s publication are subject to change without notice. Upon action of the governing body, facilities may be enlarged or otherwi se altered, courses added or deleted, and the curricula modified or expanded. Bulletin of Widener University Ser ies 1.22 • Number 6 • September 1983 (USPS #074940) Published six times a year by Widener University, once each in June. Jul y, August, and three times in September. Second class postage paid at Chester, PA 19013 . POSTMASTER: Send Fonn 3579 to: Bulletin of Widener Uni versit y, Widener Universi ty, Chester. PA 19013. ) J Bulletin of { Widener University I I 't I 1983-1984 FOR INFORMATION Widener University, Chester, PA 19013 UNIVERSITY POLICY Mr. Robert J. Bruce, President ACADEMIC POLICY Dr. Clifford T. Stewart, Provost Mr. Joseph A. Arbuckle, Assistant Provost fo r the Pennsylvania Campus Dr. Lawrence P. Buck, Dean, College of Art and Sciences Dr. Thoma G . McWill iams, Jr. , Dean, School of Engineering Dr. John T. Meli , Dean, School of Management Dr. Janette L. -

Stonybrook Estate Historic District Newport County, RI Name of Property County and State

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No.1 024-0018 (Rev. 10-90) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FORM This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Stonvbrook Estate Historic District other names/site number 2. Location street & number 501 - 521 IndianAvenue and 75 Vaucluse Avenue 0 not for publication city or town Middletown 0 vicinity state RI code RI county Newport code 005 zip code _0_28_4_2 _ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this I:8J nomination o request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property o me~¢"¢\alkf 0 does0 stadide no~. ~lIy. NN~ationalRegister(0 See continuation criteria. -

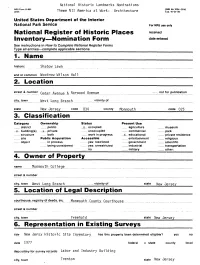

National Register of Historic Places Inventory-Nomination

National Historic Landmarks Nominations NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 (3-82) Theme VII America at Work: Architecture Exp.10-31-84 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections______ 1, Name________________ historic Shadow j-awh _ _ ____ and or common WoodrOW Wilson Hall 2. Location street & number f.Prlar AvPniie & Norwood Avenue not for publication city, town West Long Branch __ vicinity of state New Jersey code 034 county Monmouth code 025 3. Classification Category Ownership St«itus Present Use __ district __ public _x_ occupied agriculture museum _X- building(s) _x private unoccupied commercial park structure both work in oroaress x educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process yes: restricted government scientific being considered .. yes: unrestricted __ industrial transportation no _ military other: 4. Owner of Property name Monmouth College street & number city, town West Long Branch ___ vicinity of state New Jersey 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Monmouth County Courthouse street & number city, town Freehold state New Jersey 6, Representation in Existing Surveys tHIe New Jersy Historic S"[te Inventory has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1977 federal >c state county local depository for survey records Labor and Industry Building city, town Trenton state New Jersey 7. Description Condition Check one Check one _ X_ excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site __ good __ ruins X altered moved date fair _ unexposed Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance The present central building of Monmouth College is the second Shadow Lawn. -

\.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "It,- EL~PA S- ~

LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS NO. PA-t314f3 920 Spring Avenue Elkins Park Montgomery County \.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "it,- EL~PA s- ~ PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL A.ND DESCRIPTIVE Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Department of the Intericn:· p_Q_ Box 37l2'i7 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 I HABs Yt,r-" ... ELk'.'.PA,I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY $- LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS No. PA-6146 Location: 920 Spring Avenue, Elkins Park, Montgomery Co., Pennsylvania. Significance: Lynnewood Hall, designed by famed Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer in 1898, survives as one of the finest country houses in the Philadelphia area. The 110-room mansion was built for street-car magnate P.A.B. Widener to house his growing family and art collection which would later become internationally renowned. 1 The vast scale and lavish interiors exemplify the remnants of an age when Philadelphia's self-made millionaire industrialists flourished and built their mansions in Cheltenham, apart from the Main Line's old society. Description: Lynnewood Hall is a two-story, seventeen-bay Classical Revival mansion that overlooks a terraced lawn to the south. The house is constructed of limestone and is raised one half story on a stone base that forms a terrace around the perimeter of the building. The mansion is a "T" plan with the front facade forming the cross arm of the "T". Enclosed semi circular loggias extend from the east and west ends of the cross arm and a three-story wing forms the leg of the 'T' to the north. The most imposing exterior feature is the full-height, five-bay Corinthian portico with a stone staircase and a monumental pediment. -

Horace Trumbauer: a Life in Architecture

THE PennsylvanialMagazine OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Horace Trumbauer: A Life in Architecture IXT ITHIN MONTHS after g legal age, Horace Trumbauer pened his architectural office in Philadelphia. Before he died V in his native city nearly ha a century later, he had brought forth well over a thousand works. Remembered best for his mansions, he in fact devised buildings and alterations of virtually every size and purpose. Most stand in Philadelphia or its suburbs, although structures north to Maine and south to Florida, west to Colorado and east to England make him far from a local architect. While he had many gifted employees, their purpose was to carry out his intentions. Today he ranks as Phiadelphia's representative among the top tier of American architects of the Gilded Age. His life was dosely interwoven with the opulent era of architecture through which he lived. Born soon after the Civil War, the boy grew up in a nation freshly emerged as a world power, whose architects cast aside regional customs in favor of historic styles firmly within the European mainstream. Europe's own use of such styles had grown overly mannered so that the United States now led in architecture no less than in industry. First fruits of this period were still arising when Horace quit school at age fourteen to apprentice at an architectural firm. Going on his own in 1890, the twenty-one-year-old won instant approval from prosperous clients. Chief THE PENNSYLVANIA MAGAZINE OF HISTORY AND BIOGRAPHY Vol. CXXV,No. 4 (October 2001) FREDERICK PLAIT October celebrities of the era were its tycoons, and almost at once he began erecting immense residences for them.