Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

African Americans Fight for the Union the Civil War Was a Turning Point In

[Type text] African Americans Fight for the Union The Civil War was a turning point in black history for many reasons. After Lincoln’s issuance of the Emancipation Proclamation, free blacks saw their chance to fight for their country. By doing so, African Americans hoped to show their worthiness to be treated as equal citizens. However, African Americans were not exactly welcomed into the Union military with open arms. While slavery was banned in many Northern states, the border states that were fighting for the Union still allowed slavery. In addition, racist sentiments were strong in both the North and the South and many whites were not keen on training African American soldiers. In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln authorized the recruitment of African Americans into the Union army and Camp William Penn was built as a training facility for black troops. Explore the significance of Camp William Penn as a turning point in African American history in the collections of the Historical Society. Search Terms: Camp William Penn; 54th Massachusetts Regiment; Lt. Col. Louis Wagner; United States Colored Troops Recommended Collections: Abraham Barker collection on the Free Military School for Applicants for the Command of Colored Regiments (1863-1895) Collection #1968 Henry Charles Coxe letters (1861-1866) Letters from Charles Henry Coxe, a Harvard student, to his brother Frank Morrell Coxe in Philadelphia. Both Charles and Frank, enlist as commissioned officers, in units of colored troops. Charles joined the 24th U. S. C. T. Frank joined as Second -

![[Pennsylvania County Histories]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6364/pennsylvania-county-histories-16364.webp)

[Pennsylvania County Histories]

HEFEI 1ENCE y J^L v &fF i (10LLEI JTIONS S —A <f n v-- ? f 3 fCrll V, C3 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from This project is made possible by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services as administered by the Pennsylvania Department of Education through the Office of Commonwealth Libraries https://archive.org/details/pennsylvaniacoun61unse M tA R K TWAIN’S ScRdP ©GOK. DA TENTS: UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. FRANCE. June 24th, 1873. May i6th, 1877. May i 8th, 1877. TRADE MARKS: UNITED STATES. GREAT BRITAIN. Registered No. 5,896. Registered No. 15,979. DIRECTIONS. Use but little moisture, and only on ibe gummed lines. Press the scrap on without wetting it. DANIEL SLOPE A COMPANY, NEW YORK. IIsTIDEX: externaug from the Plymouth line to the Skippack road. Its lower line was From, ... about the Plymouth road, and its vpper - Hue was the rivulet running to Joseph K. Moore’s mill, in Norriton township. In 1/03 the whole was conveyed to Philip Price, a Welshman, of Upper Datef w. Merion. His ownership was brief. In the same year he sold the upper half, or 417 acres, to William Thomas, another Welshman, of Radnor. This contained LOCAL HISTORY. the later Zimmerman, Alfred Styer and jf »jfcw Augustus Styer properties. In 1706 Price conveyed to Richard Morris the The Conrad Farm, Whitpain—The Plantation •emaining 417 acres. This covered the of John Rees—Henry Conrad—Nathan Conrad—The Episcopal Corporation. present Conrad, Roberts, Detwiler, Mc¬ The present Conrad farm in Whitpain Cann, Shoemaker, Iudehaven and Hoover farms. -

PEAES Guide: the Historical Society of Pennsylvania

PEAES Guide: The Historical Society of Pennsylvania http://www.librarycompany.org/Economics/PEAESguide/hsp.htm Keyword Search Entire Guide View Resources by Institution Search Guide Institutions Surveyed - Select One The Historical Society of Pennsylvania 1300 Locust Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 215-732-6200 http://www.hsp.org Overview: The entries in this survey highlight some of the most important collections, as well as some of the smaller gems, that researchers will find valuable in their work on the early American economy. Together, they are a representative sampling of the range of manuscript collections at HSP, but scholars are urged to pursue fruitful lines of inquiry to locate and use the scores of additional materials in each area that is surveyed here. There are numerous helpful unprinted guides at HSP that index or describe large collections. Some of these are listed below, especially when they point in numerous directions for research. In addition, the HSP has a printed Guide to the Manuscript Collections of the Historical Society of Pennsylvania (HSP: Philadelphia, 1991), which includes an index of proper names; it is not especially helpful for searching specific topics, item names, of subject areas. In addition, entries in the Guide are frequently too brief to explain the richness of many collections. Finally, although the on-line guide to the manuscript collections is generally a reproduction of the Guide, it is at present being updated, corrected, and expanded. This survey does not contain a separate section on land acquisition, surveying, usage, conveyance, or disputes, but there is much information about these subjects in the individual collections reviewed below. -

The ^Penn Collection

The ^Penn Collection A young man, William Penn fell heir to the papers of his distinguished father, Admiral Sir William Penn. This collec- A tion, the foundation of the family archives, Penn carefully preserved. To it he added records of his own, which, with the passage of time, constituted a large accumulation. Just before his second visit to his colony, Penn sought to put the most pertinent of his American papers in order. James Logan, his new secretary, and Mark Swanner, a clerk, assisted in the prepara- tion of an index entitled "An Alphabetical Catalogue of Pennsylvania Letters, Papers and Affairs, 1699." Opposite a letter and a number in this index was entered the identifying endorsement docketed on the original manuscript, and, to correspond with this entry, the letter and number in the index was added to the endorsement on the origi- nal document. When completed, the index filled a volume of about one hundred pages.1 Although this effort showed order and neatness, William Penn's papers were carelessly kept in the years that followed. The Penn family made a number of moves; Penn was incapacitated and died after a long illness; from time to time, business agents pawed through the collection. Very likely, many manuscripts were taken away for special purposes and never returned. During this period, the papers were in the custody of Penn's wife; after her death in 1726, they passed to her eldest son, John Penn, the principal proprietor of Pennsylvania. In Philadelphia, there was another collection of Penn deeds, real estate maps, political papers, and correspondence. -

La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle Magazine University Publications Summer 1974 La Salle Magazine Summer 1974 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine Recommended Citation La Salle University, "La Salle Magazine Summer 1974" (1974). La Salle Magazine. 140. https://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/lasalle_magazine/140 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle Magazine by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SUMMER 1974 JONES and CUNNINGHAM of The Newsroom A QUARTERLY LA SALLE COLLEGE MAGAZINE Volume 18 Summer, 1974 Number 3 Robert S. Lyons, Jr., ’61, Editor Joseph P. Batory, ’64, Associate Editor James J. McDonald, ’58, Alumni News ALUMNI ASSOCIATION OFFICERS John J. McNally, ’64, President Joseph M. Gindhart, Esq., ’58, Executive Vice President Julius E. Fioravanti, Esq., ’53, Vice President Ronald C. Giletti, ’62, Secretary Catherine A. Callahan, ’71, Treasurer La Salle M agazine is published quarterly by La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141, for the alumni, students, faculty and friends of the college. Editorial and business offices located at the News Bureau, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Second class postage paid at Philadelphia, Penna. Changes of address should be sent at least 30 days prior to publication of the issue with which it is to take effect, to the Alumni Office, La Salle College, Philadelphia, Penna. 19141. Member of the American Alumni Council and Ameri can College Public Relations Association. -

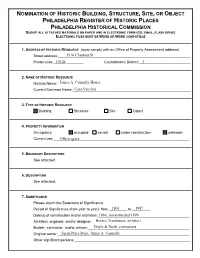

View Nomination

NOMINATION OF HISTORIC BUILDING, STRUCTURE, SITE, OR OBJECT PHILADELPHIA REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES PHILADELPHIA HISTORICAL COMMISSION SUBMIT ALL ATTACHED MATERIALS ON PAPER AND IN ELECTRONIC FORM (CD, EMAIL, FLASH DRIVE) ELECTRONIC FILES MUST BE WORD OR WORD COMPATIBLE 1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________________________________________3910 Chestnut St ________ Postal code:_______________19104 Councilmanic District:__________________________3 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:__________________________________________________________James A. Connelly House ________ Current/Common Name:________Casa Vecchia___________________________________________ ________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Occupancy: occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________Office space ________ 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION See attached. 6. DESCRIPTION See attached. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach the Statement of Significance. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1806 to _________1987 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_____________________________________1866; reconstructed 1896 _________ Architect, engineer, and/or designer:________________________________________Horace Trumbauer, architect _________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:__________________________________________Doyle & Doak, contractors _________ Original -

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3Xcerchant and Slave Trader

'Robert Sllis, Philadelphia <3XCerchant and Slave Trader ENNSYLVANIA, in common with other Middle Atlantic and New England colonies, is seldom considered as a trading center for PNegro slaves. Its slave traffic appears small and unimportant when compared, for example, with the Negro trade in such southern plantation colonies as Virginia and South Carolina. During 1762, the peak year of the Pennsylvania trade, only five to six hundred slaves were imported and sold.1 By comparison, as early as 1705, Virginia imported more than 1,600 Negroes, and in 1738, 2,654 Negroes came into South Carolina through the port of Charleston alone.2 Nevertheless, to many Philadelphia merchants the slave trade was worthy of more than passing attention. At least one hundred and forty-one persons, mostly Philadelphia merchants but also some ship captains from other ports, are known to have imported and sold Negroes in the Pennsylvania area between 1682 and 1766. Men of position and social prominence, these slave traders included Phila- delphia mayors, assemblymen, and members of the supreme court of the province. There were few more important figures in Pennsyl- vania politics in the eighteenth century than William Allen, member of the trading firm of Allen and Turner, which was responsible for the sale of many slaves in the colony. Similarly, few Philadelphia families were more active socially than the well-known McCall family, founded by George McCall of Scotland, the first of a line of slave traders.3 Robert Ellis, a Philadelphia merchant, was among the most active of the local slave merchants. He had become acquainted with the 1 Darold D. -

Martin's Bench and Bar of Philadelphia

MARTIN'S BENCH AND BAR OF PHILADELPHIA Together with other Lists of persons appointed to Administer the Laws in the City and County of Philadelphia, and the Province and Commonwealth of Pennsylvania BY , JOHN HILL MARTIN OF THE PHILADELPHIA BAR OF C PHILADELPHIA KKKS WELSH & CO., PUBLISHERS No. 19 South Ninth Street 1883 Entered according to the Act of Congress, On the 12th day of March, in the year 1883, BY JOHN HILL MARTIN, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington, D. C. W. H. PILE, PRINTER, No. 422 Walnut Street, Philadelphia. Stack Annex 5 PREFACE. IT has been no part of my intention in compiling these lists entitled "The Bench and Bar of Philadelphia," to give a history of the organization of the Courts, but merely names of Judges, with dates of their commissions; Lawyers and dates of their ad- mission, and lists of other persons connected with the administra- tion of the Laws in this City and County, and in the Province and Commonwealth. Some necessary information and notes have been added to a few of the lists. And in addition it may not be out of place here to state that Courts of Justice, in what is now the Com- monwealth of Pennsylvania, were first established by the Swedes, in 1642, at New Gottenburg, nowTinicum, by Governor John Printz, who was instructed to decide all controversies according to the laws, customs and usages of Sweden. What Courts he established and what the modes of procedure therein, can only be conjectur- ed by what subsequently occurred, and by the record of Upland Court. -

In 1848 the Slave-Turned-Abolitionist Frederick Douglass Wrote In

The Union LeagUe, BLack Leaders, and The recrUiTmenT of PhiLadeLPhia’s african american civiL War regimenTs Andrew T. Tremel n 1848 the slave-turned-abolitionist Frederick Douglass wrote in Ithe National Anti-Slavery Standard newspaper that Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, “more than any other [city] in our land, holds the destiny of our people.”1 Yet Douglass was also one of the biggest critics of the city’s treatment of its black citizens. He penned a censure in 1862: “There is not perhaps anywhere to be found a city in which prejudice against color is more rampant than Philadelphia.”2 There were a number of other critics. On March 4, 1863, the Christian Recorder, the official organ of the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, commented after race riots in Detroit, “Even here, in the city of Philadelphia, in many places it is almost impossible for a respectable colored per- son to walk the streets without being assaulted.”3 To be sure, Philadelphia’s early residents showed some mod- erate sympathy with black citizens, especially through the Pennsylvania Abolition Society, but as the nineteenth century progressed, Philadelphia witnessed increased racial tension and a number of riots. In 1848 Douglass wrote in response to these pennsylvania history: a journal of mid-atlantic studies, vol. 80, no. 1, 2013. Copyright © 2013 The Pennsylvania Historical Association This content downloaded from 128.118.152.206 on Wed, 09 Jan 2019 20:56:18 UTC All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms pennsylvania history attitudes, “The Philadelphians were apathetic and neglectful of their duty to the black community as a whole.” The 1850s became a period of adjustment for the antislavery movement. -

SAMUEL POWEL GRIFFITTS* by WILLIAM S

SAMUEL POWEL GRIFFITTS* By WILLIAM S. MIDDLETON, M.D. MADISON, WISCONSIN Men like ourselves know how hard it is drew. Yet the mark of his efforts re- to live up to the best standards of medical mains in a number of institutions in duty; know, also, what temptations, intel- his native city and his private and pro- lectual and moral, positive and negative, fessional life might well serve as a assail us all, and can understand the value model to our troubled and restless and beauty of certain characters, which, generation in medicine. like surely guided ships, have left no per- manent trace behind them on life’s great Born to William and Abigail Powel seas, of their direct and absolute devotion Griffitts in Philadelphia on July 21, to duty. ... Of this precious type was 1759, Samuel Powel Griffitts was their Samuel Powel Griffitts. third and last child. Upon the passing of his father his early training devolved HUS spoke S. Weir Mitchell on his mother. His piety and close ad- of the subject of this sketch in herence to the Quaker faith unques- his “Commemorative Address tionably reflected this influence, but upon the Centennial Anni- to the mother may also be attributed Tversary of the Institution of the Collegehis linguistic facility and knowledge of of Physicians of Philadelphia.” the classics. Young Griffitts’ academic Such a characterization at the hands course began in the College of Phila- of so acute and astute an observer of delphia in 1776 and was marked only human nature captivates the interest by a recognition of his superior grasp and imagination. -

\.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "It,- EL~PA S- ~

LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS NO. PA-t314f3 920 Spring Avenue Elkins Park Montgomery County \.\Aes Pennsylvania PA "it,- EL~PA s- ~ PHOTOGRAPHS WRITTEN HISTORICAL A.ND DESCRIPTIVE Historic American Buildings Survey National Park Service Department of the Intericn:· p_Q_ Box 37l2'i7 Washington, D.C. 20013-7127 I HABs Yt,r-" ... ELk'.'.PA,I HISTORIC AMERICAN BUILDINGS SURVEY $- LYNNEWOOD HALL HABS No. PA-6146 Location: 920 Spring Avenue, Elkins Park, Montgomery Co., Pennsylvania. Significance: Lynnewood Hall, designed by famed Philadelphia architect Horace Trumbauer in 1898, survives as one of the finest country houses in the Philadelphia area. The 110-room mansion was built for street-car magnate P.A.B. Widener to house his growing family and art collection which would later become internationally renowned. 1 The vast scale and lavish interiors exemplify the remnants of an age when Philadelphia's self-made millionaire industrialists flourished and built their mansions in Cheltenham, apart from the Main Line's old society. Description: Lynnewood Hall is a two-story, seventeen-bay Classical Revival mansion that overlooks a terraced lawn to the south. The house is constructed of limestone and is raised one half story on a stone base that forms a terrace around the perimeter of the building. The mansion is a "T" plan with the front facade forming the cross arm of the "T". Enclosed semi circular loggias extend from the east and west ends of the cross arm and a three-story wing forms the leg of the 'T' to the north. The most imposing exterior feature is the full-height, five-bay Corinthian portico with a stone staircase and a monumental pediment. -

The Presidents House in Philadelphia: the Rediscovery of a Lost Landmark

The Presidents House in Philadelphia: The Rediscovery of a Lost Landmark I R MORE THAN 150 YEARS there has been confusion about the fPresident's House in Philadelphia (fig. 1), the building which served s the executive mansion of the United States from 1790 to 1800, the "White House" of George Washington and John Adams. Congress had named Philadelphia the temporary national capital for a ten-year period while the new Federal City (now Washington, D.C.) was under con- struction, and one of the finest houses in Philadelphia was selected for President Washington's residence and office. Prior to its tenure as the President's House, the building had housed such other famous (or infamous) residents as proprietary governor Richard Penn, British general Sir William Howe, American general Benedict Arnold, French consul John Holker, and financier Robert Morris. Historians have long recognized the importance of the house, and many have attempted to tell its story, but most of them have gotten the facts wrong about how the building looked when Washington and Adams lived there, and even about where it stood. 1 am indebted to John Alviti, Penelope Hartshorne Batcheler, George Brighitbill, Mr. and Mrs. Nathaniel Burt, Jeffrey A- Cohen, William Creech, David Dashiell, Scott DeHaven, Susan Drinan, Kenneth Fmkel, Jeffrey Faherty, Marsha Fritz, Kristen Froehlich, Roy Harker, Sharon Ann Holt, Sue Keeler, Roger G. Kennedy, Bruce Laverty, Edward Lawler, Sr., Jack and Alice-Mary Lawler, Joann Lawler, Andrea Ashby Lerari, Mark Fraze Lloyd, Barbara A. McMillan, Jefferson M. Moak, Howell T. Morgan, Gene Morris, Roger W. Moss, C.