Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wonders of Germany & Austria

WONDERS OF GERMANY & AUSTRIA with Oberammergau 2020 7 May 2020 15 Days from $5,499 This tour takes advantage of the European spring season, with the beauty and mild weather. There’ll be plenty of time to enjoy some of the great German-speaking cities of central Europe – Berlin, Dresden and Vienna; experiencing the life, culture, religion and history of these cities. Archdeacon John Davis leads this tour, his second time to Oberammergau. He is the former Vicar General of the Anglican Diocese of Wangarattta. John has led several groups to Assisi, as well as to Oberammergau. Archdeacon John Davis Tour INCLUSIONS • 12 nights’ accommodation at 4 star hotels as listed • Oberammergau package including 1 nights (or similar) with breakfast daily accommodation, category 2 ticket and dinner • 5 dinners in hotels; 3 dinners in local restaurants • Services of a professional English-speaking Travel • Lunch at the Hofbrahaus Director throughout. Local expert guides where required & as noted on the itinerary • Sightseeing and entrance fees as outlined in the itinerary • Tips to Travel Director and Driver • Luxury air-conditioned coach with panoramic • Archdeacon John Davis as your host windows myselah.com.au 1300 230 271 ITINERARY Summarised Friday 8 May Saturday 16 May BERLIN OBERAMMERGAU Free day to explore. Drive to Oberammergau (travel time approx. 90 mins). Spend some free time in the quaint village Saturday 9 May before the Passion Play performance beings BERLIN at 2.30pm. There is a dinner break followed Today we will visit the two cathedrals in the Mitte by the second half of the play, concluding at area (Berlin Cathedral and St Hedwig’s) before an approximately 10.30pm. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1930, Volume 25, Issue No. 1

A SC &&• 1? MARYLAND HlSTOEICAL MAGAZIISrE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXV BALTIMORE 1930 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXV. A REGISTER OP THE CABINET MAKERS AND ALLIED TRADES IN MARY- LAND AS SHOWN BY THE NEWSPAPERS AND DIRECTORIES, 1746 TO 1820. By Henry J. Berkley, M.D., 1 COLONIAL RECORDS OP WORCESTER COUNTY. Contributed iy Louis Dow Scisco, 28 DESCENDANTS OP FRANCIS CALVERT (1751-1823). By John Bailey Culvert Nicklin, ------ ---30 REV. MATTHEW HILL TO RICHARD BAXTER, 49 EXTRACTS PROM ACCOUNT AND LETTER BOOKS OP DR. CHARLES CARROLL, OP ANNAPOLIS, 53, 284 BENJAMIN HENRY LATKOBE TO DAVID ESTB, 77 PROCEEDINGS OP THE SOCIETY, ------ 78, 218, 410 NOTES, CORRECTIONS, ETC., 95, 222, 319 LIST OP MEMBERS OP THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, - - 97 SOMETHING MOKE OP THE GREAT CONPEDERATB GENERAL, " STONE- WALL " JACKSON AND ONE OP HIS HUMBLE FOLLOWERS IN THE SOUTH OF YESTERYEAR. By DeCourcy W. Thorn, - - 129 DURHAM COUNTY: LORD BALTIMORE'S ATTEMPT AT SETTLEMENT OP HIS LANDS ON THE DELAWARE BAY, 1670-1685. By Percy O. Skirven, ---------- 157 A SKETCH OP THOMAS HARWOOD ALEXANDER, CHANCERY COUNCEL- LOR OP MARYLAND, 1801-1871. By Henry J. Berkley, - - 167 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1850-1851. By L. E. Blauch, 169 THE COMMISSARY IN COLONIAL MARYLAND. By Edith E. MacQueen, 190 COLONIAL RECORDS OP FREDERICK COUNTY. Contributed by Louis Dow Sisco, 206 MARYLAND RENT ROLLS, 209 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1864. By L. E. Blauch, 225 THE ABINGTONS OF ST. MARY'S AND CALVERT COUNTIES. By Henry J. Berkley, 251 BALTIMORE COUNTY RECORDS OF 1668 AND 1669. -

Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE International Projects with a Local Emphasis: Collecting and Representing Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Daniel A. Powazek June 2020 Thesis Committee: Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson Dr. Randolph Head Dr. Jeanette Kohl Copyright by Daniel A. Powazek 2020 The Thesis of Daniel A. Powazek is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS International Projects with a Local Emphasis: The Collecting and Representation of Saxon Identity in the Dresden Kunstkammer and Princely Monuments in Freiberg Cathedral by Daniel A. Powazek Master of Arts, Graduate Program in Art History University of California, Riverside, June 2020 Dr. Kristoffer Neville, Chairperson When the Albertine Dukes of Saxony gained the Electoral privilege in the second half of the sixteenth century, they ascended to a higher echelon of European princes. Elector August (r. 1553-1586) marked this new status by commissioning a monumental tomb in Freiberg Cathedral in Saxony for his deceased brother, Moritz, who had first won the Electoral privilege for the Albertine line of rulers. The tomb’s magnificence and scale, completed in 1563, immediately set it into relation to the grandest funerary memorials of Europe, the tombs of popes and monarchs, and thus establishing the new Saxon Electors as worthy peers in rank and status to the most powerful rulers of the period. By the end of his reign, Elector August sought to enshrine the succeeding rulers of his line in an even grander project, a dynastic chapel built into Freiberg Cathedral directly in front of the tomb of Moritz. -

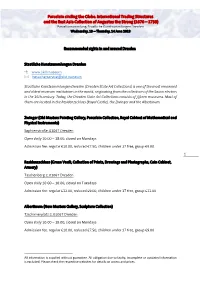

Porcelain Circling the Globe. International Trading Structures And

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of twelve museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

OPTICAL OBJECTS in the DRESDEN KUNSTKAMMER: LUCAS BRUNN and the COURTLY DISPLAY of KNOWLEDGE Sven Dupré and Michael Korey* Intr

OPTICAL OBJECTS IN THE DRESDEN KUNSTKAMMER: LUCAS BRUNN AND THE COURTLY DISPLAY OF KNOWLEDGE Sven Dupré and Michael Korey* Introduction The museum situation that we see today in Dresden is the consequence of a radical reorganization of the Saxon court collections by Friedrich August I (August the Strong) in the 1720s.1 One of the steps in this restructuring was the formation of a distinct, specialized collection of scientifi c instruments, which is the basis of the Mathematisch- Physikalischer Salon. This reorganization effectively ended two centuries’ development of the Kunstkammer,2 the vast early modern collection in Saxony thought to have been founded around 1560 by Elector August.3 It was principally in the context of this Kunstkammer that ‘scientifi c instruments’ were collected in Dresden in the course of the 16th and 17th centuries. We will sketch the evolution of the Dresden Kunstkammer * The research of the fi rst author has been made possible by the award of a post- doctoral fellowship and a research grant of the Research Foundation—Flanders. 1 On this reorganization of the collections, see Dirk Syndram, Die Schatzkammer Augusts des Starken. Von der Pretiosensammlung zum Grünen Gewölbe, Dresden-Leipzig, 1999, and Helen Watanabe-O’Kelly, Court Culture in Dresden: From Renaissance to Baroque, New York, Palgrave, 2002, ch. 7. 2 Even after its reorganization under August the Strong, a truncated torso of the Kunstkammer in fact continued to be displayed—including a gallery of fi ne clocks and automata—until its fi nal dissolution in 1832. Many of the remaining items were then absorbed into several other Dresden court collections: the Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vault), the Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, and the Historisches Museum, now once again known as the Rüstkammer (Armoury). -

Der Weg Der Roten Fahne. Art in Correlation to Architecture, Urban Planning and Policy

JOURNAL OF ARCHITECTURE AND URBANISM ISSN 2029-7955 print / ISSN 2029-7947 online 2013 Volume 37(4): 292–300 doi:10.3846/20297955.2013.866861 Theme of the issue “Architectural education – discourses of tradition and innovation” Žurnalo numerio tema „Architektūros mokymas – tradicijų ir naujovių diskursai“ DER WEG DER ROTEN FAHNE. ART IN CORRELATION TO ARCHITECTURE, URBAN PLANNING AND POLICY Christiane Fülscher Department History of Architecture, University of Stuttgart, Keplerstrasse 11, 70174 Stuttgart, Germany E-mail: [email protected] Received 03 October 2013; accepted 04 November 2013 Abstract. The presented research focuses on the relationship between art and architecture. On the example of the mural Der Weg der Roten Fahne (The Path of the Red Flag) installed at the western façade of the Kulturpalast Dresden (Palace of Culture in Dresden) the author analyses the necessity of the mural as an immanent element to communicate political decisions of the German Democratic Republic’s government to the public by using architecture. Up until now the mural reinforces the political value of the International Style building in function and shape and links its volume to the urban layout. Keywords: architecture, culture house, German Democratic Republic, International Style, monumental art, mural, political archi- tecture, representation, Socialist Realism, urban planning. Reference to this paper should be made as follows: Fülscher, Ch. 2013. Der Weg der Roten Fahne. Art in correlation to architecture, urban planning and policy, Journal of Architecture and Urbanism 37(4): 292–300. Introduction The mural Der Weg der Roten Fahne An artefact that is designed in collaboration with ar- In 1969 a collective of the Dresden Academy of Fine chitecture depends on its context. -

The Saber's Many Travels (The Origins of the Cross-Cutting Art)

Bartosz Sieniawski Warsaw, 4th February 2013 Janusz Sieniawski The Saber’s Many Travels (The Origins of the Cross-Cutting Art) Before you engage in combat, mind this: the blade of you saber is nothing else – and cannot be anything else – but an extension of your own arm, and equally: your entire arm, from the armpit right to the hand which is grasping the hilt, is nothing else but an extended grip of the saber. (Michał Starzewski, of the Ostoja coat of arms) Some remarks on the history of the saber: The curved saber first emerged on the steppes of Central Asia amongst the nomadic peoples. It reached the Middle East in 7th century AD via Arab traders, who had good trade relations with the nomads. A while later, the Arabs conquered the Sassanid Persian Empire and assimilated the conquered nations, which meant that the saber could spread across the region in a relatively short time, becoming an ever-present element of the Islamic world. In the 9th century saber was commonly used as a weapon by Huns, Avars, Cumans, Bulgars, Turks and Hungarians, whose influx threatened to flood Europe. Miniatures in the Byzantine chronicles of Skylitzes show bands of warriors of Turkic-Tartar origin, who inhabited the regions around the Caspian Sea, mostly Pechenges and Kipchaks, armed with spears and long sabers. In the 12th century, again thanks to the nomadic peoples, the saber was introduced in China, India and in Rus, and four hundred years later, via Turkey and Hungary, it finally arrived in Poland. It is quite unparalleled for a single weapon type to be in use by warriors, knights and soldiers on battlefields across the world and to remain almost unchanged for hundreds of years (from 5th to 20th century). -

Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762)

Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) IRENA BIEŃKOWSKA University of Warsaw Institute of Musicology Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) Musicology Today • Vol. 10 • 2013 DOI: 10.2478/muso-2014-0004 For years, Polish musicologists have looked closely at differences in the quantity and quality of stored music, musical activity at the courts of Polish nobility. These architectural monuments and works of art). efforts have resulted in numerous study papers (which A recent study by the present author of materials are mostly fragmentary in nature) analysing musical collected at the Central Archives of Historical Records ensembles active in the courts, theatrical centres, and in Warsaw (hereinafter: AGAD) has yielded new findings the playing of music by the nobles themselves. The about music at the court of Stanisław Poniatowski main problem faced by researchers is the fragmented (1676–1762), the governor of the Mazovia Province, and state of collections, or simply their non-existence. The bearer of the Ciołek family coat of arms. The Poniatowski work becomes time-consuming and arduous, and it lies Family Archive (hereinafter: ARP) section of AGAD was beyond the scope of a typical musicological research, as investigated with a view to a better understanding of the information sources are quite scattered, incomplete and musical activity at the governor’s court3. typically not primary in nature. Stanisław Poniatowski, who is considered to have Research to date into sources from 18th-century courts brought about the Poniatowski family’s rise in power, and has not been carried out in a systematic fashion, and who was the father of the future king of the Republic has only looked at individual representatives of major of Poland, came from a noble, but not particularly aristocratic families from the Republic of Poland, such as affluent family. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Bach's Organ World Tour of Germany

Bach’s Organ World Tour of Germany for Organists & Friends June 2 - 11, 2020 (10 days, 8 nights) There will be masterclasses and opportunity for organists to play many of the organs visited. Non- organists are welcome to hear about/listen to the organs or explore the tour cities in more depth Day 1 - Tuesday, June 2 Departure Overnight flights to Berlin, Germany (own arrangements or request from Concept Tours). Day 2 - Wednesday, June 3 Arrival/Dresden Guten Tag and welcome to Berlin! (Arrival time to meet for group transfer tbd.) Meet your English-speaking German tour escort who’ll be with you throughout the tour. Board your private bus for transfer south to Dresden, a Kunststadt (City of Art) along the graceful Elbe River. Dresden’s glorious architecture was reconstructed in advance of the city’s 800th anniversary. Highlights include the elegant Zwinger Palace and the baroque Hofkirche (Court Church). Check in to hotel for 2 nights. Welcome dinner and overnight. Day 3 - Thursday, June 4 Dresden This morning enjoy a guided walking tour of Dresden. Some of the major sights you'll see: the Frauenkirche; Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister (Painting Gallery of Old Masters); inside the Zwinger; the majestic Semper Opera House; Grünes Gewölbe (Green Vaults); the Brühlsche Terrasse overlooking the River Elbe. Free time afterwards for your own explorations. 3pm Meet at the Kreuzkirche to attend the organ recital “Orgel Punkt 3”. Visit Hofkirche and have a resident organist (tbc) demonstrate the Silbermann organ, followed by some organ time for members. Day 4 - Friday, June 5 Freiberg/Pomssen/Leipzig After breakfast, check out, board bus and depart.