The Saber's Many Travels (The Origins of the Cross-Cutting Art)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Augustus II the Strong's Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches

Augustus II the Strong’s Porcelain Collection at the Japanisches Palais zu Dresden: A Visual Demonstration of Power and Splendor Zifeng Zhao Department of Art History & Communication Studies McGill University, Montreal September 2018 A thesis submitted to McGill University in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts © Zifeng Zhao 2018 i Abstract In this thesis, I examine Augustus II the Strong’s porcelain collection in the Japanisches Palais, an 18th-century Dresden palace that housed porcelains collected from China and Japan together with works made in his own Meissen manufactory. I argue that the ruler intended to create a social and ceremonial space in the chinoiserie style palace, where he used a systematic arrangement of the porcelains to demonstrate his kingly power as the new ruler of Saxony and Poland. I claim that such arrangement, through which porcelains were organized according to their colors and styles, provided Augustus II’s guests with a designated ceremonial experience that played a significant role in the demonstration of the King’s political and financial prowess. By applying Gérard de Lairesse’s color theory and Samuel Wittwer’s theory of “the phenomenon of sheen” to my analysis of the arrangement, I examine the ceremonial functions of such experience. In doing so, I explore the three unique features of porcelain’s materiality—two- layeredness, translucency and sheen. To conclude, I argue that the secrecy of the technology of porcelain’s production was the key factor that enabled Augustus II’s demonstration of power. À travers cette thèse, j'examine la collection de porcelaines d'Auguste II « le Fort » au Palais Japonais, un palais à Dresde du 18ème siècle qui abritait des porcelaines provenant de Chine, du Japon et de sa propre manufacture à Meissen. -

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P

Pedigree of the Wilson Family N O P Namur** . NOP-1 Pegonitissa . NOP-203 Namur** . NOP-6 Pelaez** . NOP-205 Nantes** . NOP-10 Pembridge . NOP-208 Naples** . NOP-13 Peninton . NOP-210 Naples*** . NOP-16 Penthievre**. NOP-212 Narbonne** . NOP-27 Peplesham . NOP-217 Navarre*** . NOP-30 Perche** . NOP-220 Navarre*** . NOP-40 Percy** . NOP-224 Neuchatel** . NOP-51 Percy** . NOP-236 Neufmarche** . NOP-55 Periton . NOP-244 Nevers**. NOP-66 Pershale . NOP-246 Nevil . NOP-68 Pettendorf* . NOP-248 Neville** . NOP-70 Peverel . NOP-251 Neville** . NOP-78 Peverel . NOP-253 Noel* . NOP-84 Peverel . NOP-255 Nordmark . NOP-89 Pichard . NOP-257 Normandy** . NOP-92 Picot . NOP-259 Northeim**. NOP-96 Picquigny . NOP-261 Northumberland/Northumbria** . NOP-100 Pierrepont . NOP-263 Norton . NOP-103 Pigot . NOP-266 Norwood** . NOP-105 Plaiz . NOP-268 Nottingham . NOP-112 Plantagenet*** . NOP-270 Noyers** . NOP-114 Plantagenet** . NOP-288 Nullenburg . NOP-117 Plessis . NOP-295 Nunwicke . NOP-119 Poland*** . NOP-297 Olafsdotter*** . NOP-121 Pole*** . NOP-356 Olofsdottir*** . NOP-142 Pollington . NOP-360 O’Neill*** . NOP-148 Polotsk** . NOP-363 Orleans*** . NOP-153 Ponthieu . NOP-366 Orreby . NOP-157 Porhoet** . NOP-368 Osborn . NOP-160 Port . NOP-372 Ostmark** . NOP-163 Port* . NOP-374 O’Toole*** . NOP-166 Portugal*** . NOP-376 Ovequiz . NOP-173 Poynings . NOP-387 Oviedo* . NOP-175 Prendergast** . NOP-390 Oxton . NOP-178 Prescott . NOP-394 Pamplona . NOP-180 Preuilly . NOP-396 Pantolph . NOP-183 Provence*** . NOP-398 Paris*** . NOP-185 Provence** . NOP-400 Paris** . NOP-187 Provence** . NOP-406 Pateshull . NOP-189 Purefoy/Purifoy . NOP-410 Paunton . NOP-191 Pusterthal . -

Maryland Historical Magazine, 1930, Volume 25, Issue No. 1

A SC &&• 1? MARYLAND HlSTOEICAL MAGAZIISrE PUBLISHED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY VOLUME XXV BALTIMORE 1930 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XXV. A REGISTER OP THE CABINET MAKERS AND ALLIED TRADES IN MARY- LAND AS SHOWN BY THE NEWSPAPERS AND DIRECTORIES, 1746 TO 1820. By Henry J. Berkley, M.D., 1 COLONIAL RECORDS OP WORCESTER COUNTY. Contributed iy Louis Dow Scisco, 28 DESCENDANTS OP FRANCIS CALVERT (1751-1823). By John Bailey Culvert Nicklin, ------ ---30 REV. MATTHEW HILL TO RICHARD BAXTER, 49 EXTRACTS PROM ACCOUNT AND LETTER BOOKS OP DR. CHARLES CARROLL, OP ANNAPOLIS, 53, 284 BENJAMIN HENRY LATKOBE TO DAVID ESTB, 77 PROCEEDINGS OP THE SOCIETY, ------ 78, 218, 410 NOTES, CORRECTIONS, ETC., 95, 222, 319 LIST OP MEMBERS OP THE MARYLAND HISTORICAL SOCIETY, - - 97 SOMETHING MOKE OP THE GREAT CONPEDERATB GENERAL, " STONE- WALL " JACKSON AND ONE OP HIS HUMBLE FOLLOWERS IN THE SOUTH OF YESTERYEAR. By DeCourcy W. Thorn, - - 129 DURHAM COUNTY: LORD BALTIMORE'S ATTEMPT AT SETTLEMENT OP HIS LANDS ON THE DELAWARE BAY, 1670-1685. By Percy O. Skirven, ---------- 157 A SKETCH OP THOMAS HARWOOD ALEXANDER, CHANCERY COUNCEL- LOR OP MARYLAND, 1801-1871. By Henry J. Berkley, - - 167 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1850-1851. By L. E. Blauch, 169 THE COMMISSARY IN COLONIAL MARYLAND. By Edith E. MacQueen, 190 COLONIAL RECORDS OP FREDERICK COUNTY. Contributed by Louis Dow Sisco, 206 MARYLAND RENT ROLLS, 209 EDUCATION AND THE MARYLAND CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION, 1864. By L. E. Blauch, 225 THE ABINGTONS OF ST. MARY'S AND CALVERT COUNTIES. By Henry J. Berkley, 251 BALTIMORE COUNTY RECORDS OF 1668 AND 1669. -

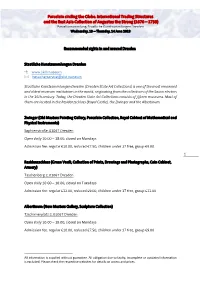

Recommended Sights in and Around Dresden1

Porcelain circling the Globe. International Trading Structures and the East Asia Collection of Augustus the Strong (1670 – 1733) Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden Wednesday, 13 – Thursday, 14 June 2018 Recommended sights in and around Dresden1 Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden www.skd.museum [email protected] Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden (Dresden State Art Collections) is one of the most renowned and oldest museum institutions in the world, originating from the collections of the Saxon electors in the 16th century. Today, the Dresden State Art Collections consists of fifteen museums. Most of them are located in the Residenzschloss (Royal Castle), the Zwinger and the Albertinum. Zwinger (Old Masters Painting Gallery, Porcelain Collection, Royal Cabinet of Mathematical and Physical Instruments) Sophienstraße, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 1 Residenzschloss (Green Vault, Collection of Prints, Drawings and Photographs, Coin Cabinet, Armory) Taschenberg 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Tuesdays Admission fee: regular €12.00, reduced €9.00, children under 17 free, group €11.00 Albertinum (New Masters Gallery, Sculpture Collection) Tzschirnerplatz 2, 01067 Dresden Open daily 10:00 – 18:00, closed on Mondays Admission fee: regular €10.00, reduced €7.50, children under 17 free, group €9.00 All information is supplied without guarantee. All obligation due to faulty, incomplete or outdated -

Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762)

Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) IRENA BIEŃKOWSKA University of Warsaw Institute of Musicology Research into the Resources of Polish Courts. Notes on the Musicians of Stanisław Ciołek Poniatowski (1676–1762) Musicology Today • Vol. 10 • 2013 DOI: 10.2478/muso-2014-0004 For years, Polish musicologists have looked closely at differences in the quantity and quality of stored music, musical activity at the courts of Polish nobility. These architectural monuments and works of art). efforts have resulted in numerous study papers (which A recent study by the present author of materials are mostly fragmentary in nature) analysing musical collected at the Central Archives of Historical Records ensembles active in the courts, theatrical centres, and in Warsaw (hereinafter: AGAD) has yielded new findings the playing of music by the nobles themselves. The about music at the court of Stanisław Poniatowski main problem faced by researchers is the fragmented (1676–1762), the governor of the Mazovia Province, and state of collections, or simply their non-existence. The bearer of the Ciołek family coat of arms. The Poniatowski work becomes time-consuming and arduous, and it lies Family Archive (hereinafter: ARP) section of AGAD was beyond the scope of a typical musicological research, as investigated with a view to a better understanding of the information sources are quite scattered, incomplete and musical activity at the governor’s court3. typically not primary in nature. Stanisław Poniatowski, who is considered to have Research to date into sources from 18th-century courts brought about the Poniatowski family’s rise in power, and has not been carried out in a systematic fashion, and who was the father of the future king of the Republic has only looked at individual representatives of major of Poland, came from a noble, but not particularly aristocratic families from the Republic of Poland, such as affluent family. -

Timeline1800 18001600

TIMELINE1800 18001600 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 8000BCE Sharpened stone heads used as axes, spears and arrows. 7000BCE Walls in Jericho built. 6100BCE North Atlantic Ocean – Tsunami. 6000BCE Dry farming developed in Mesopotamian hills. - 4000BCE Tigris-Euphrates planes colonized. - 3000BCE Farming communities spread from south-east to northwest Europe. 5000BCE 4000BCE 3900BCE 3800BCE 3760BCE Dynastic conflicts in Upper and Lower Egypt. The first metal tools commonly used in agriculture (rakes, digging blades and ploughs) used as weapons by slaves and peasant ‘infantry’ – first mass usage of expendable foot soldiers. 3700BCE 3600BCE © PastSearch2012 - T i m e l i n e Page 1 Date York Date Britain Date Rest of World 3500BCE King Menes the Fighter is victorious in Nile conflicts, establishes ruling dynasties. Blast furnace used for smelting bronze used in Bohemia. Sumerian civilization developed in south-east of Tigris-Euphrates river area, Akkadian civilization developed in north-west area – continual warfare. 3400BCE 3300BCE 3200BCE 3100BCE 3000BCE Bronze Age begins in Greece and China. Egyptian military civilization developed. Composite re-curved bows being used. In Mesopotamia, helmets made of copper-arsenic bronze with padded linings. Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, first to use iron for weapons. Sage Kings in China refine use of bamboo weaponry. 2900BCE 2800BCE Sumer city-states unite for first time. 2700BCE Palestine invaded and occupied by Egyptian infantry and cavalry after Palestinian attacks on trade caravans in Sinai. 2600BCE 2500BCE Harrapan civilization developed in Indian valley. Copper, used for mace heads, found in Mesopotamia, Syria, Palestine and Egypt. Sumerians make helmets, spearheads and axe blades from bronze. -

Porcelain Acquisitions Through Private Networks for Augustus the Strong, Heidelberg: Arthistoricum.Net, 2020

1. Introduction Ever since the discovery of the maritime routes to America by Christopher Columbus in 1492, and to India by Vasco da Gama in 1498, the global expansion of trade and trade routes influenced European culture in an unprecedented man- ner. Knowledge about geography and foreign nations expanded, and the intro- duction of new consumables such as tea and chocolate transformed European table culture. Silk and fine cottons from China and India, once brought to the West via the Silk Roads, now arrived in large quantities at the European courts. The European global expansion had its downsides, of course. The conquest of the Americas led to the expulsion, exploitation and eradication of its indigenous peoples. The trade in sugar cane products became the linchpin of colonial rule on the Caribbean islands. After the extinction of almost the entire native pop- ulation, large areas became available for cultivation. Millions of Africans were deported and enslaved over the course of 400 years to work on the plantations under inhuman conditions. One trade item, which also found its way to Europe with the growing maritime traffic, was Chinese porcelain. Still a mysterious substance in the 16th century, vessels made from the luxurious-looking material quickly gained wide popularity with the intensification of the export trade by the Dutch. Millions of East Asian porcelains reached Europe in the 17th and 18th centuries, partly through the professional East Asia trading companies and partly through private enterprise. Chinese and – later – Japanese porcelain soon became deeply anchored in European culture, where it was used for its intended purpose as tableware, as gifts exchanged between royal courts, or as decorative and useful items in the households of even the general public. -

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age

Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Advisory Board Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska, Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Published within the Project HERA (Humanities in the European Research Area) – JRP (Joint Research Programme) Music Migrations in the Early Modern Age: The Meeting of the European East, West, and South (MusMig) Music Migration in the Early Modern Age Centres and Peripheries – People, Works, Styles, Paths of Dissemination and Influence Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska, Eds. Warsaw 2016 Liber Pro Arte English Language Editor Shane McMahon Cover and Layout Design Wojciech Markiewicz Typesetting Katarzyna Płońska Studio Perfectsoft ISBN 978-83-65631-06-0 Copyright by Liber Pro Arte Editor Liber Pro Arte ul. Długa 26/28 00-950 Warsaw CONTENTS Jolanta Guzy-Pasiak, Aneta Markuszewska Preface 7 Reinhard Strohm The Wanderings of Music through Space and Time 17 Alina Żórawska-Witkowska Eighteenth-Century Warsaw: Periphery, Keystone, (and) Centre of European Musical Culture 33 Harry White ‘Attending His Majesty’s State in Ireland’: English, German and Italian Musicians in Dublin, 1700–1762 53 Berthold Over Düsseldorf – Zweibrücken – Munich. Musicians’ Migrations in the Wittelsbach Dynasty 65 Gesa zur Nieden Music and the Establishment of French Huguenots in Northern Germany during the Eighteenth Century 87 Szymon Paczkowski Christoph August von Wackerbarth (1662–1734) and His ‘Cammer-Musique’ 109 Vjera Katalinić Giovanni Giornovichi / Ivan Jarnović in Stockholm: A Centre or a Periphery? 127 Katarina Trček Marušič Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Migration Flows in the Territory of Today’s Slovenia 139 Maja Milošević From the Periphery to the Centre and Back: The Case of Giuseppe Raffaelli (1767–1843) from Hvar 151 Barbara Przybyszewska-Jarmińska Music Repertory in the Seventeenth-Century Commonwealth of Poland and Lithuania. -

The Catholic Church in Polish History, Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-40281-3 272 APPENDIX – TIMELINE, 966–2016

APPENDIX – TIMELINE, 966–2016 966: Duke Mieszko’s conversion to Christianity 997: Beheading of Bishop Adalbert of Prague (known in Poland as Wojciech) 1022: Revolt against the Piast dynasty, with pagan participation 1066: Revolt by pagans 1140: Arrival of the Cistercian Order in Poland 1215: The Fourth Lateran Council, which made annual confession and communion mandatory for all Christians 1241: Invasion of Eastern Europe, including Poland, by a Tatar (Muslim) army 1337–1341: Renewed war with the Tatars 1386: Founding, through marriage, of the Jagiellonian dynasty 1378–1417: The Great Schism, with rival popes sitting in Avignon and Rome and, beginning in 1409, with a third pope residing in Pisa 1454–1466: The Thirteen Years’ War 1520: The Edict of Thorn (Toruń), by which the King of Poland banned the importation of Martin Luther’swritings into Poland 1529: The first siege of Vienna by Ottoman forces 1551–1553: New Testament published in Polish 1563: First translation of the entire Bible into Polish 1564: Arrival of the Jesuit Order in Poland © The Author(s) 2017 271 S.P. Ramet, The Catholic Church in Polish History, Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy, DOI 10.1057/978-1-137-40281-3 272 APPENDIX – TIMELINE, 966–2016 1569: The Union of Lublin, merging the Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania into a single, federated Commonwealth 1577–1578: Lutherans granted freedom of worship in Poland 1596: The Union of Brest, bring a large number of Orthodox parishes into union with Rome as Eastern-Rite Catholics 1655–1660: -

Σαυρομαται Or Σαρμαται? in Search of the Original Form *

Eos C 2013 / fasciculus extra ordinem editus electronicus ISSN 0012-7825 ΣΑΥΡΟΜΑΤΑΙ OR ΣΑΡΜΑΤΑΙ? IN SEARCH OF THE ORIGINAL FORM * By STaNiSŁaW ROSPoND The Indo-Europeanist and Slavist onomast receives from the classical philolo- gist priceless onomastic source material; priceless, because it is strictly speaking “literary”, or original, since Greek and Roman authors – the historiographers and geographers, often simultaneously diplomats, strategists and merchants; even their philosophers and poets – listed foreign ethnonyms, hydronyms, oronyms and even toponyms in their works. The borders of the oikoumene shifted for the Greek settler and merchant; already in the 8th and 7th centuries BC the restless Ionians founded cities on the Black Sea (such as Olbia and Tyras). Generals and traders would conquer ever new lands in Europe and Asia for the Roman Empire. That was the route along which the earliest geographical and ethnographic reconnaissance proceeded of those regions called Scythia, Dacia, Moesia, Sarmatia etc. Ionian logographers, especially Hecataeus and Xanthus, the excellent historian Herodotus and his suc- cessors – Ephorus, Pseudo-Scylax, Pseudo-Scymnus, the historian Polybius, the geographers Strabo and Ptolemy – provide us with very rich onomastic material for European and Asian peoples. Finally, Roman authors of the Imperial period (Pomponius Mela, Pliny the Elder, Tacitus and others) besides traditional Greek sources had their own, based on the military and commercial intelligence of the Roman Empire, which in its efforts to defend its territories from the attacks of the Celts, Thracians, Scythians, Sarmatians, Slavs and Germans took care to have those lands well mapped, even in the cartographic sense. There was on the one hand cartography, more or less faithfully rendering the geographical nomenclature learned by the author himself or from military and commercial reports; and on the other, literature, or more exactly “literary arm- * Originally published in Polish in “Eos” LV 1965, fasc. -

The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Electoral Saxony in the Early Eighteenth Century: Crisis and Cooperation

THE Polish-LITHUANIAN COMMONWEALTH AND ELECTORAL SAXONY IN THE EARLY EIGHTEENTH CENTURY: CRISIS AND COOPERATION Adam Perłakowski The Polish-Saxon union between 1697 and 1763 has been an important topic of historical research for some time now. The nearly seventy years of shared history are, to be sure, reflected in monographs and essays, but many aspects of this relationship remain largely unfamiliar even today. That is hardly surprising, since the Prussocentric historiography of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (one might mention Friedrich Förster, Gustav Droysen and Paul Haake) was highly successful in asserting its con- struct of the historic mission of Friderician Prussia to unite the German states under Prussian leadership. And there was no room here for a Saxony that, embroiled as it was in the foreign interests of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, moved slowly but surely towards utter decline. There was thus little justification for a greater interest in the history of Poland and Saxony under Augustus II (‘the Strong’) and Augustus III. After 1945, official GDR historiography also saw no need to uncover the secrets of the so-called Saxon period of Poland-Lithuania A few East German historians did address the question of mutual economic relations.1 In Poland too, extremely negative and stubborn stereotypes persist to this day about the ‘Saxon period’ as a ‘dark’ era of backwardness, defeat, disputatious aristocrats and—horror of horrors!—plans for the partition of Poland, which Augustus II allegedly presented to Prussian ministers.2 Thanks to the pioneering work of Józef Andrzej Gierowski and later of Jacek Staszewski we now possess a good deal of important new informa- tion about the rule of the two Wettins on the Polish throne, and Gier- owski himself, together with Johannes Kalisch, initiated the first joint conference of Polish and—in those days East—German historians on the Polish-Saxon Union, the proceedings of which were published in 1 J. -

Przeszłość W Kulturze Średniowiecznej Polski Tom 1.Indd

Indeks osób Aaron bibl. 724, 728, 736 Agius z Corvey 658 Aaron, bp krakowski, abp 324, 325, 328– Agnieszka (Maria) z Andechs-Meran, kró- 332, 717 lowa Francji, ż. Filipa II Augusta 237, 696 Aba Samuel, król Węgier 42 Agnieszka Babenberg, księżna śląska i kra- Abdalonymus, król Sydonu 280 kowska, ż. Władysława Wygnańca 117, Abdiasz bibl. 736 119–124, 234, 236 Abel bibl. 486, 564, 645, 727, 736 Agnieszka Niemiecka, księżna Szwabii d’Abetot Urse 196 i mar grabina Austrii 234 Abgarowicz Kazimierz 63, 90, 107 Agnieszka von Rochlitz, księżna Meranii 696 Abiker Séverine 319, 344 Agnieszka z Rzymu św. 567, 571, 603, 641, Abraham bibl. 490, 491, 554, 556, 560, 584, 679, 681, 683, 733, 742 648, 649, 736 Agosti Gianfranco 620 Absalom (Absalon) bibl. 73, 736 Alan mit. 295 Achab bibl. 726 Alan z Auxerre 567, 596 Achiasz bibl. 726 Alan z Lille 521, 533, 534, 536, 609, 652 Achilles mit. 96, 121, 129, 137 Al-Azmeh Aziz 33 Ackley Joseph Salvatore 406 Albert III z Everstein 234 Adalbert, abp magdeburski 47, 48, 55 Albert IV z Everstein 234 Adalbold z Utrechtu 53 Albert Wielki św. 341, 548 Adam bibl. 208, 247, 346, 486, 554, 562, Albert, wójt Krakowa 464 645, 647–649, 651, 686, 736 Alberyk z Trois-Fontaines 9, 16, 207–239 Adam Świnka z Zielonej 575 Alcmeonius z Krotony 536 Adam z Bremy 214, 720 Alcock Leslie 481 Adam z Książa 566 Aleksander de Villa Dei (z Villedieu) 426, Adamczyk Monika 84, 380, 415, 416 437, 486, 487, 531 Adamska Anna 369 Aleksander I, papież 732, 734 Adelajda, ż.