Evaluation Process and Methods Used

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Figure 1. Southern Sudan's Protected Areas

United Nations Development Programme Country: Sudan PROJECT DOCUMENT Launching Protected Area Network Management and Building Capacity in Post-conflict Project Title: Southern Sudan By end of 2012, poverty especially among vulnerable groups is reduced and equitable UNDAF economic growth is increased through improvements in livelihoods, food security, decent Outcome(s): employment opportunities, sustainable natural resource management and self reliance; UNDP Strategic Plan Environment and Sustainable Development Primary Outcome: Catalyzing access to environmental finance UNDP Strategic Plan Secondary Outcome: Mainstreaming environment and energy Expected CP Outcome(s): Strengthened capacity of national, sub-national, state and local institutions and communities to manage the environment and natural disasters to reduce conflict over natural resources Expected CPAP Output(s) 1. National and sub-national, state and local institutions and communities capacities for effective environmental governance, natural resources management, conflict and disaster risk reduction enhanced. 2. Comprehensive strategic frameworks developed at national and sub-national levels regarding environment and natural resource management Executing Entity/Implementing Partner: NGO Execution Modality – WCS in cooperation with the Ministry of Wildlife Conservation and Tourism of the Government of Southern Sudan (MWCT-GoSS) Implementing Entity/Responsible Partners: United Nations Development Programme Brief Description The current situation Despite the 1983 to 2005 civil war, many areas of Southern Sudan still contain areas of globally significant habitats and wildlife populations. For example, Southern Sudan contains one of the largest untouched savannah and woodland ecosystems remaining in Africa as well as the Sudd, the largest wetland in Africa, of inestimable value to the flow of the River Nile, the protection of endemic species and support of local livelihoods. -

Linkages-Success-Stories-South-Sudan

JULY 2016 SUCCESS STORY Success on Several Levels in South Sudan In South Sudan, obtaining HIV care and treatment is difficult for people living with HIV. Only 10 percent of those eligible are currently enrolled on antiretroviral therapy (ART). But for one key population — female sex workers (FSWs) — the barriers to comprehensive HIV care and treatment are particularly daunting. Many sex workers cannot afford to lose income while waiting for services at overburdened hospitals. And those who do seek care often find providers are reluctant to serve them because of the stigma associated with sex work. Recruiting and retaining FSWs and other key populations (KPs) into the HIV cascade of services is a complex issue that demands a response at many levels. In South Sudan, LINKAGES is helping to generate a demand for services, improve access to KP-friendly services, and create a policy environment that is more conducive to the health rights of key populations. GENERATING DEMAND FOR SERVICES The justified mistrust that FSWs have for the health care system keeps many from seeking the services they need. Peer education and outreach is a critical component of engaging KPs in the HIV cascade. LINKAGES South Sudan conducted a mapping exercise to identify hotspots (or key locations) where sex work takes place. From these locations, 65 FSWs were identified and trained as peer educators to lead participatory education sessions among their peers. The sessions are designed to motivate FSWs to adopt healthy behaviors and develop the skills to do so. The sessions cover topics like condom use, regular screening and treatment for sexually transmitted infections (STIs), periodic testing for HIV, and enrollment into care and treatment services for those living with HIV. -

Magwi County

Resettlement, Resource Conflicts, Livelihood Revival and Reintegration in South Sudan A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County by N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Department of International Environment and Development No. Report Noragric Studies 5 8 RESETTLEMENT, RESOURCE CONFLICTS, LIVELIHOOD REVIVAL AND REINTEGRATION IN SOUTH SUDAN A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County By N. Shanmugaratnam Noragric Report No. 58 December 2010 Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences, UMB Noragric is the Department of International Environment and Development Studies at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB). Noragric’s activities include research, education and assignments, focusing particularly, but not exclusively, on developing countries and countries with economies in transition. Noragric Reports present findings from various studies and assignments, including programme appraisals and evaluations. This Noragric Report was commissioned by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad) under the framework agreement with UMB which is administrated by Noragric. Extracts from this publication may only be reproduced after prior consultation with the employer of the assignment (Norad) and with the consultant team leader (Noragric). The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed in this publication are entirely those of the authors and cannot be attributed directly to the Department of International Environment and Development Studies (UMB/Noragric). Shanmugaratnam, N. Resettlement, resource conflicts, livelihood revival and reintegration in South Sudan: A study of the processes and institutional issues at the local level in Magwi County. Noragric Report No. 58 (December 2010) Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) P.O. -

Deadly Profits: Illegal Wildlife Trafficking Through Uganda And

Cover: The carcass of an elephant killed by militarized poachers. Garamba National Park, DRC, April 2016. Photo: African Parks Deadly Profits Illegal Wildlife Trafficking through Uganda and South Sudan By Ledio Cakaj and Sasha Lezhnev July 2017 Executive Summary Countries that act as transit hubs for international wildlife trafficking are a critical, highly profitable part of the illegal wildlife smuggling supply chain, but are frequently overlooked. While considerable attention is paid to stopping illegal poaching at the chain’s origins in national parks and changing end-user demand (e.g., in China), countries that act as midpoints in the supply chain are critical to stopping global wildlife trafficking. They are needed way stations for traffickers who generate considerable profits, thereby driving the market for poaching. This is starting to change, as U.S., European, and some African policymakers increasingly recognize the problem, but more is needed to combat these key trafficking hubs. In East and Central Africa, South Sudan and Uganda act as critical waypoints for elephant tusks, pangolin scales, hippo teeth, and other wildlife, as field research done for this report reveals. Kenya and Tanzania are also key hubs but have received more attention. The wildlife going through Uganda and South Sudan is largely illegally poached at alarming rates from Garamba National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Sudan, points in West Africa, and to a lesser extent Uganda, as it makes its way mainly to East Asia. Worryingly, the elephant -

The War(S) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace

Conflict Research Programme The War(s) in South Sudan: Local Dimensions of Conflict, Governance, and the Political Marketplace Flora McCrone in collaboration with the Bridge Network About the Authors Flora McCrone is an independent researcher based in East Africa. She has specialised in research on conflict, armed groups, and political transition across the Horn region for the past nine years. Flora holds a master’s degree in Human Rights from LSE and a bachelor’s degree in Anthropology from Durham University. The Bridge Network is a group of eight South Sudanese early career researchers based in Nimule, Gogrial, Yambio, Wau, Leer, Mayendit, Abyei, Juba PoC 1, and Malakal. The Bridge Network members are embedded in the communities in which they conduct research. The South Sudanese researchers formed the Bridge Network in November 2017. The team met annually for joint analysis between 2017-2020 in partnership with the Conflict Research Programme. About the Conflict Research Programme The Conflict Research Programme is a four-year research programme hosted by LSE IDEAS, the university’s foreign policy think tank. It is funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office. Our goal is to understand and analyse the nature of contemporary conflict and to identify international interventions that ‘work’ in the sense of reducing violence or contributing more broadly to the security of individuals and communities who experience conflict. © Flora McCrone and the Bridge Network, February 2021. This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License which permits use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

Magwe County, Eastern Equatoria State

INTER-AGENCY ASSESSMENT REPORT OF THE LRA AFFECTED POPULATIONS Magwe County, Eastern Equatoria State 19 - 22 September 2006 Emergency Preparedness and Response (EP&R) Unit, OCHA Background: The Lord Resistance Army (LRA) activities have destabilised the security situation of the area and severely affected the livelihood of the ordinary residents in Magwe county and other southern areas bordering with Uganda. Over the past 15 years when the LRA was active in Magwe County, the populations have been living in fear of attacks, properties and assets were looted and or destroyed. Repeated LRA incursions have caused recurrent displacement of ordinary civilians. High level peace talks among the LRA, the Government of Uganda and the GoSS over the past few months have resulted in signing of the “Cessation of Hostility” peace truce and paved the way for further discussions towards bringing a permanent solution to the problem. During the first week of September 2006, Dr. Riek Machar Teny, Vice President of South Sudan with other senior GoSS officials visited a number of locations in the county including Owiny-Ki-Bol (assembly area), Magwe, Pajok (Parajok) and Pogee (along the Sudan Uganda border) to sensitize communities on the progress of the LRA peace talks. As agreed in the Cessation of Hostilities document the LRA soldiers and the associated population will be gathered and encamped in Southern Sudan (Eastern Equatoria, Magwe County – Owiny-ki-Bol and in Nabanga of Western Equatoria) for the duration of the peace talks which is ongoing in Juba. Due to past insecurity, the population in Magwe County has been neglected both in terms of humanitarian as well as development assistance. -

Symptoms and Causes: Insecurity and Underdevelopment in Eastern

sudanHuman Security Baseline Assessment issue brief Small Arms Survey Number 16 April 2010 Symptoms and causes Insecurity and underdevelopment in Eastern Equatoria astern Equatoria state (EES) is The survey was supplemented by qual- 24,789 (± 965) households in the one of the most volatile and itative interviews and focus group three counties contain at least one E conflict-prone states in South- discussions with key stakeholders in firearm. ern Sudan. An epicentre of the civil EES and Juba in January 2010. Respondents cited traditional lead- war (1983–2005), EES saw intense Key findings include: ers (clan elders and village chiefs) fighting between the Sudanese Armed as the primary security providers Across the entire sample, respond- Forces (SAF) and the Sudan People’s in their areas (90 per cent), followed ents ranked education and access Liberation Army (SPLA), as well by neighbours (48 per cent) and reli- to adequate health care as their numerous armed groups supported gious leaders (38 per cent). Police most pressing concerns, followed by both sides, leaving behind a legacy presence was only cited by 27 per by clean water. Food was also a top of landmines and unexploded ordnance, cent of respondents and the SPLA concern in Torit and Ikotos. Security high numbers of weapons in civilian by even fewer (6 per cent). ranked at or near the bottom of hands, and shattered social and com- Attitudes towards disarmament overall concerns in all counties. munity relations. were positive, with around 68 per When asked about their greatest EES has also experienced chronic cent of the total sample reporting a security concerns, respondents in food insecurity, a lack of basic services, willingness to give up their firearms, Torit and Ikotos cited cattle rustling, and few economic opportunities. -

South Sudan's Renewable Energy Potential

UNITED STATES INSTITUTE OF PEACE www.usip.org SPECIAL REPORT 2301 Constitution Ave., NW • Washington, DC 20037 • 202.457.1700 • fax 202.429.6063 ABOUT THE REPORT David Mozersky and Daniel M. Kammen In the context of the civil war with no end in sight in South Sudan, this report outlines how a donor-led shift from the current total reliance on diesel to renewable energy can deliver short-term humanitarian cost savings while creating a longer- term building block for peace in the form of a clean energy infrastructure. The report is supported by the Africa South Sudan’s Renewable program at the United States Institute of Peace. ABOUT THE AUTHORS Energy Potential David Mozersky is the cofounder of Energy Peace Partners and the founding director of the Program on Conflict, Climate Change and Green Development at the University of California, A Building Block for Peace Berkeley’s Renewable and Appropriate Energy Lab. He has been involved with peacebuilding and conflict resolution efforts in South Sudan for more than fifteen years. Daniel Kammen is a professor and chair of the Energy and Resources Group Summary and a professor in the Goldman School of Public Policy at the University of California, Berkeley. He served as science envoy • Shortly after independence in 2011, South Sudan fell into civil war. A regional peace agree- for the US State Department in 2016 and 2017. ment has effectively collapsed, and the international community has no clear strategy on how to proceed. • The war has destroyed South Sudan’s limited infrastructure, triggering an economic implo- sion. -

Central Equatoria Eastern Equatoria Jonglei Lakes

For Humanitarian Purposes Only SOUTH SUDAN Production date: 10 Mar 2017 Eastern Equatoria State - WASH INDICATOR REACH calculated the areas more likely to have WASH needs basing the estimation on the data collected between January and February 2017 with the Area of Knowledge (AoK) approach, using the following methEodotloghy. iopia The indicator was created by averaging the percentages of key informants (KIs) reporting on the J o n g l e i following for specific settlements: - Accessibility to safe drinking water 0% indicates a reported impossibility to access safe drinking water by all KIs, while 100% indicates safe drinking water was reported accessible by each KI. Only assessed settlements are shown on the map. Values for different settlements have been averaged L a k e s and represented with hexagons 10km wide. Kapoeta Lopa County Kapoeta East North County County C e n t r a l E a s t e r n E q u a t o r i a Imehejek E q u a t o r i a Lohutok Kapoeta South County Narus Torit Torit County Budi County Magwi Lotukei Ikotos County Pageri Parajok Magwi County Nimule Kenya Uganda Sudan 0 25 50 km Data sources: Ethiopia Settlements assessed Boundaries WASH indicator Thematic indicators: REACH Administrative boundaries: UNOCHA; State capital International 0.81 - 1 Settlements: UNOCHA; County capital 0.61 - 0.8 Coordinate System:GCS WGS 1984 C.A.R. County Contact: [email protected] Principal town 0.41 - 0.6 Note: Data, designations and boundaries contained Juba State Village 0.21 - 0.4 on this map are not warranted to be error-free and do not imply acceptance by the REACH partners, Disputed area associates, donors or any other stakeholder D.R.C. -

Weekly Update on Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Preparedness for South Sudan

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN MINISTRY OF HEALTH Weekly Update on Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) Preparedness for South Sudan Update # 29 Date: 23 March 2019 South Sudan Public Health Emergency Operations Center (PHEOC) 1. Highlights . An assessment team of UNICEF, WFP, MSF, and WHO visited Yei River State on 20 March 2019 to assess the level of readiness of the Isolation facility to handle suspected cases. The team will also travel to Nimule and Yambio for the same mission. Since 28 January 2019, a total of 1, 411 healthcare workers and frontline workers in Yei River State and Gbudwe State have been vaccinated against EVD. The GeneXpert and Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) results for the Ebola alert from Tambura were negative for Ebola Zaire and other strains. About 12 laboratory personnel were trained on EVD biosafety in Torit from 12 to 14 March 2019, participants were drawn from various counties of former Eastern Equatoria State. A suspected EVD alert was reported from Mauna police station of Jubek state. The GenXpert analysis was negative for Ebola. 2. Ebola Situation update from North Kivu of Democratic Republic of Congo . As of 23 March 2019, a total of 1,009 EVD cases, including 944 confirmed and 65 probable cases have been reported. Since the last report on 17 March 2019, 58 new confirmed EVD cases have been reported, with an additional 31 deaths. 3. Public Health Preparedness and Readiness 3.1 Coordination . National taskforce meeting was held on 21 March 2019 at the PHEOC in Juba. The meeting minutes with action points were shared for follow-up and implementation. -

Eastern Equatoria State

! Ea!stern Equatoria State Map ! ! ! ! ! ! 32°E 33°E 34°E 35°E ! ! ! Makuac ! Lyodein ! Pengko River Tigaro Mewun Bor ! ! ! ! Brong ! Boma o ! Anyidi ! Marongodoa Towoth ! ! ! n Macdit R " Gurgo i Deng Shol . Kang ! ! ! en Upper Boma e Kwal Tiu ! Karita Nyelichu ! Gurbi ! ! ! Balwan M Tukls Nongwoli Pajok ! ! . Gwa!!lla ! ! Aluk Kolnyang ! Katanich Titong R Munini ! R. K ! ! Sudan ang Wowa ! Aliab ! en ! Logoda ! Malek Bor South ! ! Jonglei Pibor !Rigl Chilimun N N ° ! Pariak Lowelli Katchikan Kichepo ° ! Pariak ! ! ! ! 6 ! ! 6 ! a Lochiret River Bellel l l ! Awerial i ! t Kenamuke Swamp ! ! ! o PanabangW L r Ngechele ! . Neria Ethiopia a h Kanopir ! Natibok Kabalatigo South i R ! ! ! w t Central e ! Moru Kimod G ! Rongada African Sudan N . i R R Tombi l Republic ! e . N R. Gwojo-Adung a Ch ! ro Kassangor alb ! Tiarki ! o !Bori ng ! ! ! Moru Kerri Kuron Gigging ! ! ! Mun! i " ! Karn Ethi Kerkeng ! ! ! ! Nakadocwa Democratic i Gemmaiza r i Republic of Congo t Kobowen Swamp Moru Ethi Borichadi Bokuna ! Poko i ! ! Uganda Wani Mika ! ! Kassengo ! Selemani ! Pagar S ! Nabwel ! Chabong Kenya ! Tukara . ! ! R River Nakua ! Kenyi Terekeka ! Moru Angbin ! Mukajo ! ! Bulu Koli Gali ) Awakot Lotimor ! t ! ! ! ! Akitukomoi i Tumu River Gera ! e ! Nanyangachor ! l Napalap l Kalaruz ! Namoropus ! i ! t ! ETHIOPIA Kangitabok Lomokori o Eyata Moru Kolinyagkopil Logono Terekeka ! ! ! ! Wit ! L ! " ( Natilup Swamp Magara Umm Gura Mwanyakapin ! ! ! R n Abuilingakine Lomareng Plateau . ! ! R N ! a R ak y . Juban l u ! ! Rambo Lokodopoto!k . ! ! a L ( a N Lomuleye Katirima Nai A S ! ! o a k ! Badigeru Swamp River Lokuja a Losagam Musha Lukwatuk Pass Doinyoro East ch ! ! ! p ! ! ! o i Buboli r ) ! o L o Pongo River Lokorowa ! Watha Peth Hills . -

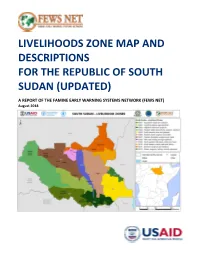

Livelihoods Zone Map and Descriptions for South Sudan

LIVELIHOODS ZONE MAP AND DESCRIPTIONS FOR THE REPUBLIC OF SOUTH SUDAN (UPDATED) A REPORT OF THE FAMINE EARLY WARNING SYSTEMS NETWORK (FEWS NET) August 2018 SOUTH SUDAN Livelihood Zone Map and Descriptions August 2018 Acknowledgements and Disclaimer This exercise was undertaken by FEWS NET and partners including the Government of South Sudan (GoSS), the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS), the National Ministry of Agriculture and Food Security (NMAFS), and UN agencies including World Food Programme (WFP) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Special thanks are extended to the core national facilitator’s team, especially John Pangech, Director General Planning, NMAFS; Abraham Arop Ayuel, Planning Officer, NMAFS; Philip Dau, Director Monitoring and Evaluation, NBS; Joice Jore, Coordinator, Food Security Technical Secretariat/NBS; John Vuga, Programme Officer, WFP/VAM; Evans Solomon Kenyi, Food Security Officer, FAO; and Mark Nyeko Acire, Food Security Officer, FAO. In addition, thanks to all state representatives who contributed inputs into the updated livelihoods zone descriptions. The Livelihood Zoning workshop and this report were led by Gavriel Langford and Daison Ngirazi, consultants to FEWS NET, with technical support from Antazio Drabe, National Technical Manager and James Guma, Assistant National Technical Manager of FEWS NET South Sudan. This report will form part of the knowledge base for FEWS NET’s food security monitoring activities in South Sudan. The publication was prepared under the United States Agency for International Development Famine Early Warning Systems Network (FEWS NET) Indefinite Quantity Contract, AID-OAA-I-12-00006, Task Order 1 (AIDOAA-TO-12-00003), TO4 (AID-OAA- TO-16-00015). The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government.